Introduction: This is an interview podcast conducted on “Picture Book Lollipop”, hosted by Xiaoxiang and guest Ajia. Starting from the reference book “Original Picture Books: Selected Readings and Highlights” published at the end of 2024, an in-depth conversation was held around the selection criteria, historical context, current themes and future development of original picture books. The recording time is on the evening of January 3, 2025, and the broadcast time is January 17, 2025.

The following text is compiled as an excerpt. To listen to the full podcast, please click the following audio link:

Microcosm:http://t.cn/A6uDFbvy

Click to open »> Part I | Part 2 | Part 3

[Part 4]

…

All the stories we tell are, in a sense, retellings of classics.

It’s just that many of us haven’t read so many stories, so we always feel that this story is new and that story is new to us.

But in my opinion, all stories are actually old stories.

Xiaoxiang:

In addition to the deepening of the story and the extension of the meaning that you just mentioned, I also particularly hope to see more diversity and richness in visual expression.

In fact, in terms of folk traditions, ours are richer than those of South Korea and Japan in terms of materials and appearance.

So when adapting folk traditions, shouldn’t our original picture books also present a richer look than those of our neighboring countries?

Ajia:

I think it also comes down to fate. After interviewing many creators, I feel that the creative process really depends on a sense of destiny.

For example, Mr. Naoki Matsui, the “Father of Picture Books” in Japan, is not only an excellent publisher, but also a very perceptive editor. He often gives completely different suggestions to different creators.

For example, when he met Teacher Cai Gao, she actually wanted to draw some stories about contemporary children’s lives, but Matsui Nao told her that she should try to create more traditional stories and use traditional techniques.

When he met Mitsumasa Anno, he suggested that he draw “travel picture books” that are more Western in style and contain more personal feelings.

Another example is Akabane Suekichi, the painter of “Suho and the White Horse”. He believes that Akabane is most suitable for creating picture books with Japanese folk flavor.

Naoki Matsui has a special sensitivity and knows what each creator is best at and what kind of stories they are best suited to telling.

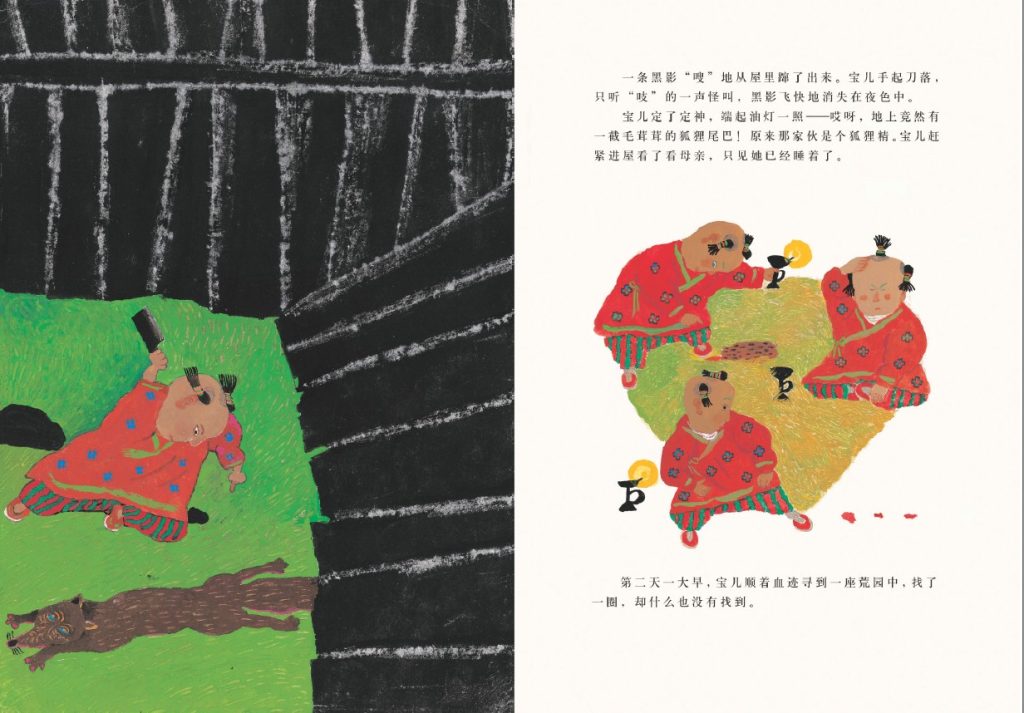

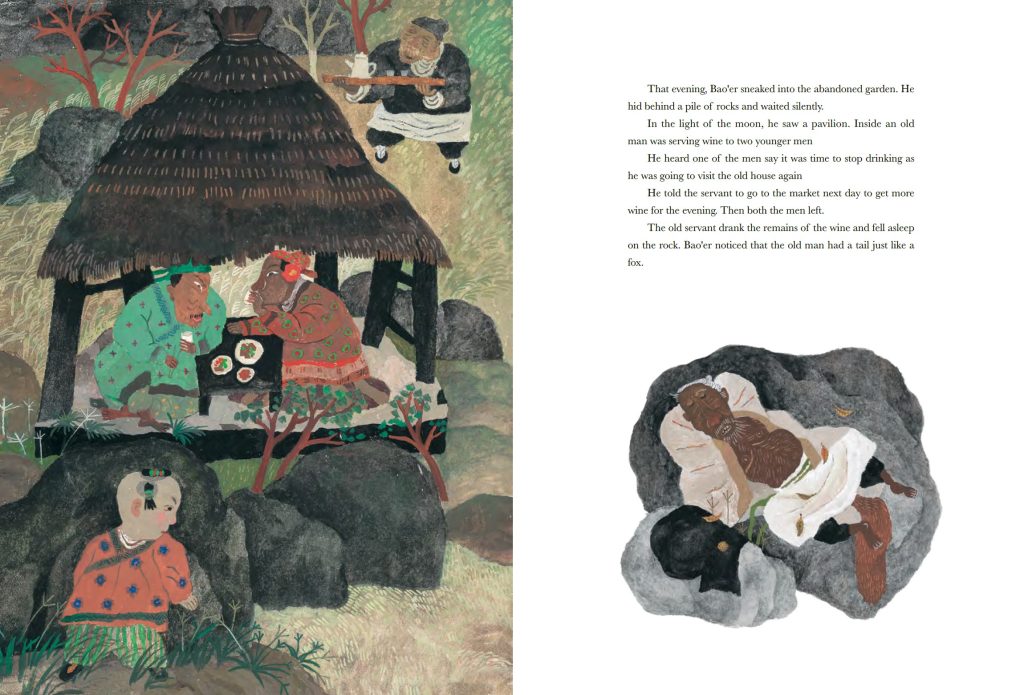

If you have the opportunity to talk to Teacher Cai Gao, you will find that she is particularly interested in stories like “Bao’er” and the themes in “Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio” that are a bit dark, elves, and ghosts.

She has her own understanding and expression of the kind of “darkness with light”, mysterious, and even scary things. The heavy writing of human nature is actually a bit of magical realism, right? She is particularly suitable for telling this kind of story.

So I think we need this kind of “opportunity” — to allow every creator to freely express what he or she wants to say most.

Each person may be just a “small group of people” who are good at expressing a certain perspective, a theme, or a certain emotion. But as long as these “small groups of people” can express themselves freely, our original picture books can form a very diverse ecosystem.

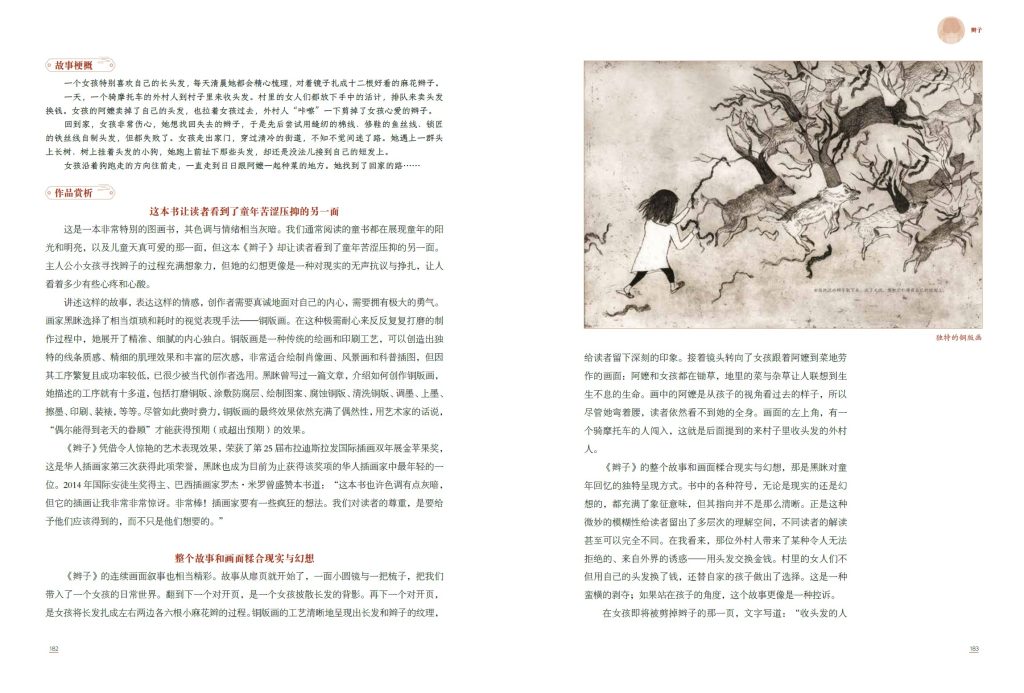

Take, for example, the book “Braids”.

-228x300.jpg)

At that time, the editorial team was discussing whether to include it or not. Many people hesitated, saying that the book was “not interesting enough for children” and “the color tone was gray”, etc. But I insisted on including it.

Why? Because this book tells a different story of childhood.

Most of our children’s books want to tell children how wonderful childhood is, but the real childhood is not always wonderful. Some children’s childhood is actually very difficult.

I know Heimi is from Chaoshan, and my mother is also from Chaoshan. Every time she recalls her childhood, she can’t help crying. Especially for women, the pressure they endure in the Chaoshan cultural environment is something that many people cannot understand.

You can’t force them to “sing about their childhood”, that’s meaningless. Of course, you can’t ask them to describe their childhood as particularly horrible, that’s not necessary either.

But Braids strikes a balance.

It expresses the pain and struggle of childhood, but also finds a way out in the story, which is the power of fantasy, and finally there is a reconciliation with grandma.

I think this story has a strong healing power. It may not be a “childhood story” in the mainstream sense, but it may resonate with many people, and make them feel comforted and even relieved.

This kind of book should not be ignored.

Of course, I have my own preferences. But what I hope more is that when our choices are diverse enough, we will find that China has always had diverse creations. It’s just that some aspects are not seen or recognized in the mainstream context.

So I also choose some stories with a bit of “darkness”, such as books like “Happy Egg Laying”.

Xiaoxiang:

We just talked about the adaptation of traditional folk stories. I would also like to talk to you about the creation of contemporary life.

I’m not sure if it’s my personal bias or I haven’t read enough, but I’ve always felt that there don’t seem to be many expressions of contemporary life in original Chinese picture books, especially those that make my eyes light up and surprise me, which don’t seem to be common.

Ajia:

It’s difficult. Of course it’s difficult, do you know?

Look at the book I listed in the next article that best expresses this theme, “Winged Boy”, right? It is a very good book, but it is not easy to keep it for a long time and continue to be read by everyone.

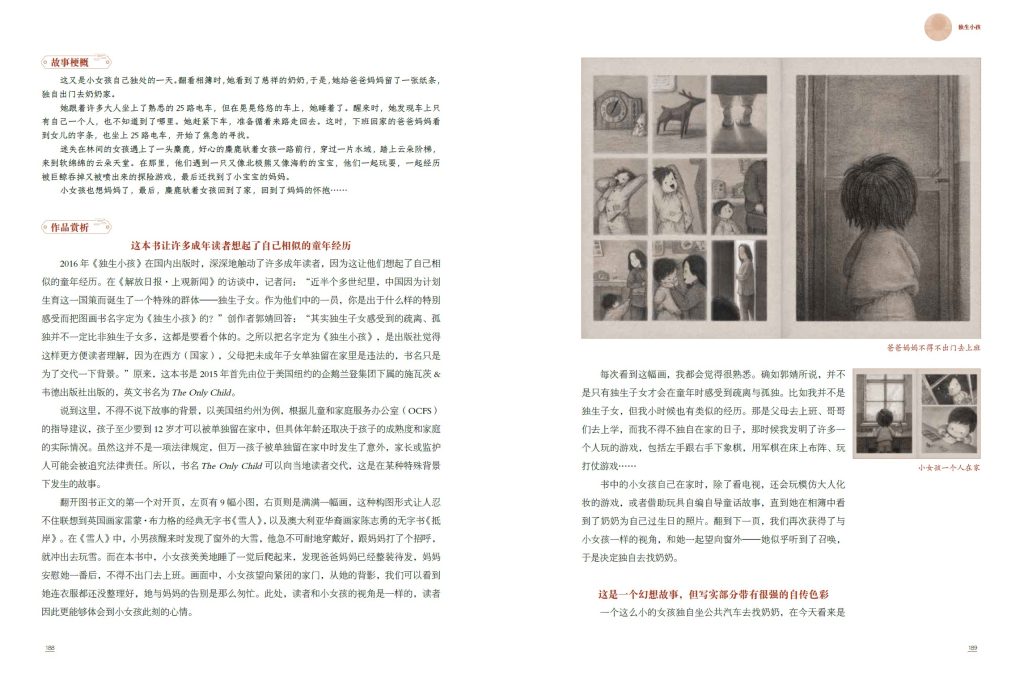

This is also true for “Only Child”. If you want to maintain an objective and truthful expression, there will always be some people who think: Is this not suitable for children? Some people also think it is not “child-friendly” enough.

In fact, there have been many debates about the “childishness” of “Winged Boy”. But sometimes, if you really want to express it realistically, it can’t be too fake, right? You can’t just express some good wishes, but you need to present it objectively.

Some sentences ended up being deleted when I was retelling the book.

The story of “Winged Boy” is about a child from a migrant worker family in a big city. No matter what he does in school, he will be excluded by other children because he always smells like cooking fumes.

You see, no matter how he behaves, others always think that he is not a “real city kid.”

But his mother had to let him help in the store while watching him do his homework. Those who came to work always wanted to talk to the child. In fact, his mother was not simply worried that he would be distracted, but she didn’t want him to have too much contact with these people. These subtle points were all observed by the creator, Teacher Liu Xun, because her daughter was the child’s classmate. In the process of helping each other, they felt the very warm humanity and also realized the side that was particularly dignified and worthy of respect.

Liu Xun also often participated in their lives, observed every detail, and then recorded it as objectively as possible.

But if we want to talk about these things, we will have many concerns. Will it offend people? Realistic topics are really difficult to talk about.

Xiaoxiang:

I remember that when I read “Only Child”, it really had a great impact on me.

That seemed to be the first time I read “my own story”.

Because I am of the same generation as the author, I feel that what she is talking about is my own growing up experience, and this sense of substitution is particularly strong.

But I also noticed that there seem to be very few picture books that children read today that can truly reflect their current lives. Do you think there will be more and more such works in original picture books in the future?

Ajia:

In fact, the expression of real childhood life——

If it just shows something particularly beautiful, is this kind of work still worth publishing?

Take, for example, “Last Stop on Market Street”. Were you moved after reading it? Right?

Some books tell stories of loss, which are equally moving and embody the caring part of life.

But if the work lacks real awareness of the problem, real observations, and valuable responses, then such work will be difficult to be convincing.

I often say that realistic works often have to “raise questions”, otherwise they become preachy.

When I talked about juvenile novels before, I often said that real juvenile novels are often “problem juvenile novels.”

If a YA novel was just about everything being wonderful, then there would be little need for it to exist, right?

The reason we write a fictional story is because there are difficulties, setbacks or shortcomings in reality.

You have to ask questions in your work and then provide some kind of real and meaningful response, rather than simply painting a pie in the sky and making the hope look pretty.

I’m very happy that a Chinese juvenile novel was recently translated and published in English. The book is called “The Tilted Sky”. The novel tells the story of a child from a single-parent family and his father, and the relationship between the two is very tense. The child has to change guardians several times… It’s a very broken growth story. But when you read to the end, you will feel something really warm.

Xiaoxiang:

What do you think of the current phenomenon of “famous works adapted into picture books”? To be honest, I have read a lot of such picture books, but there are almost no examples that I think are successful.

Ajia:

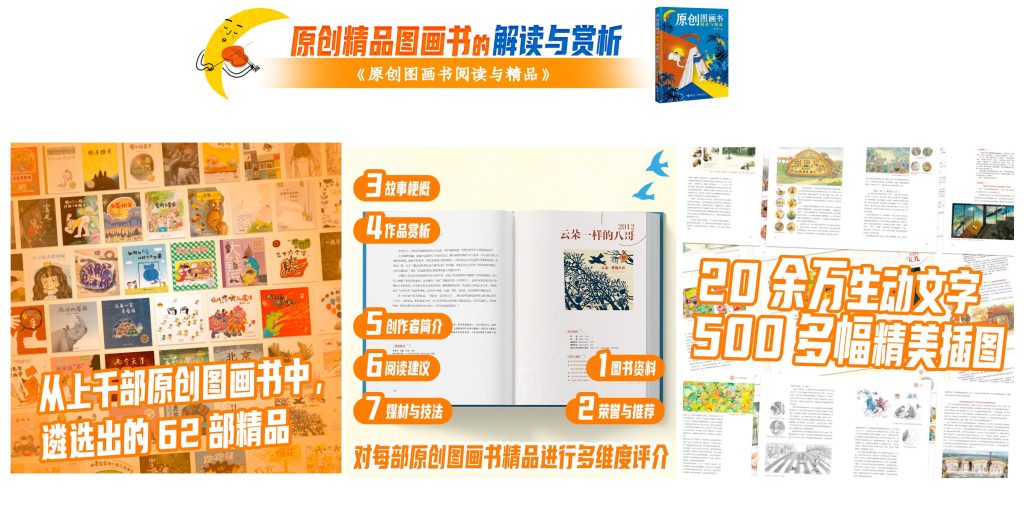

In fact, after the publication of my book “Original Picture Books: Selected Readings and Highlights”, some friends in the industry also expressed their opinions very tactfully, saying that if they were to write it, they would choose books from the perspective of “visual priority”.

You see, different people have different perspectives.

As for me, I don’t consider “beautiful illustrations” as the primary criterion for choosing a book. Of course, good illustrations are definitely a plus, but for me, the most important criterion is: the relationship between the text and the pictures. Is there a “correspondence” between the text and the pictures? Is there “progress”? Do they create a “third story” together? This is what I value. Most of the books I choose meet this criterion.

As for some people’s choice of books, they may focus more on “famous authors” and “famous works”, which is another system.

But why do you think this adaptation is not very successful? It is probably because you judge it using the “language of picture books”. You care about the closeness between the text and the pictures, not whether the pictures are simply “icing on the cake”.

Of course, sometimes we also need some beautiful illustrations to appreciate classics, and I like this kind of books, but that may not be the definition of a picture book, it is more like an illustrated version of a book.

As a picture book, I particularly emphasize the close coordination between text and pictures.

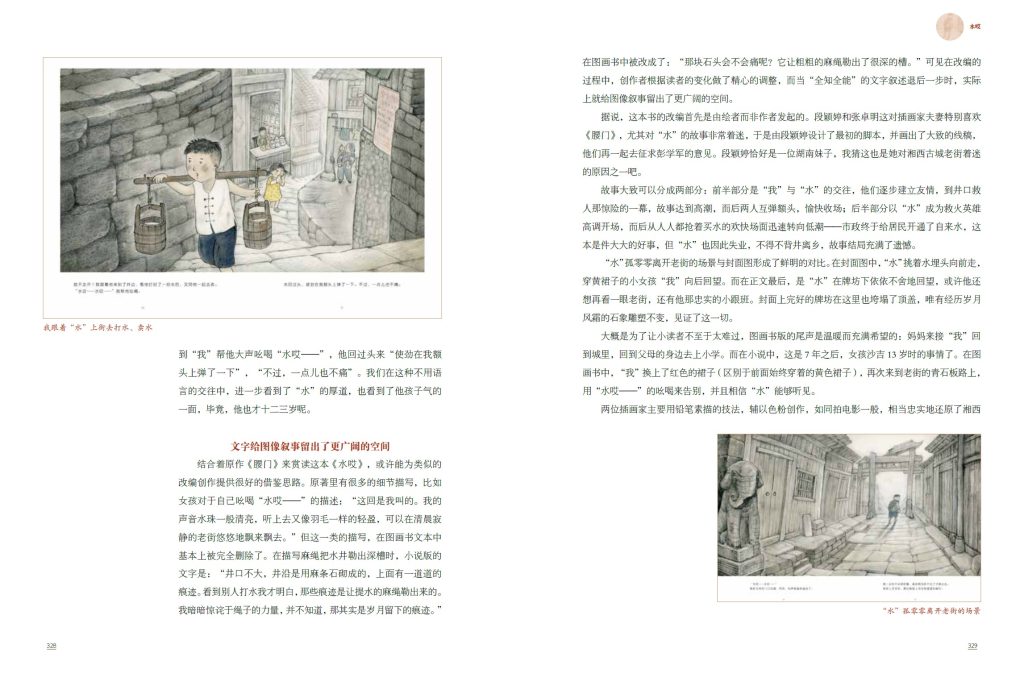

For example, the story “Shui Ai” selected in my book is adapted from Peng Xuejun’s novel “Waist Gate”. However, this adaptation was not initiated by the author of the novel at all, but two illustrators took the initiative to find the author and said that they particularly liked this story and wanted to turn it into a picture book.

They also drew sketches, prepared drafts, and then sought the author’s approval. So this is actually a “visual creator-led” adaptation.

In that book review, I also specifically mentioned the difference between picture books and novel texts——

There are a lot of psychological descriptions and processes in the novel, but these are not suitable for picture books, so they are basically deleted, leaving only a very concise narrative, coupled with continuous visual narrative. The two are matched perfectly, so it becomes a real picture book.

I think this is a “special case”. It was the illustrator’s efforts that pushed the adaptation forward and made it a “new work”, just like an adapted movie.

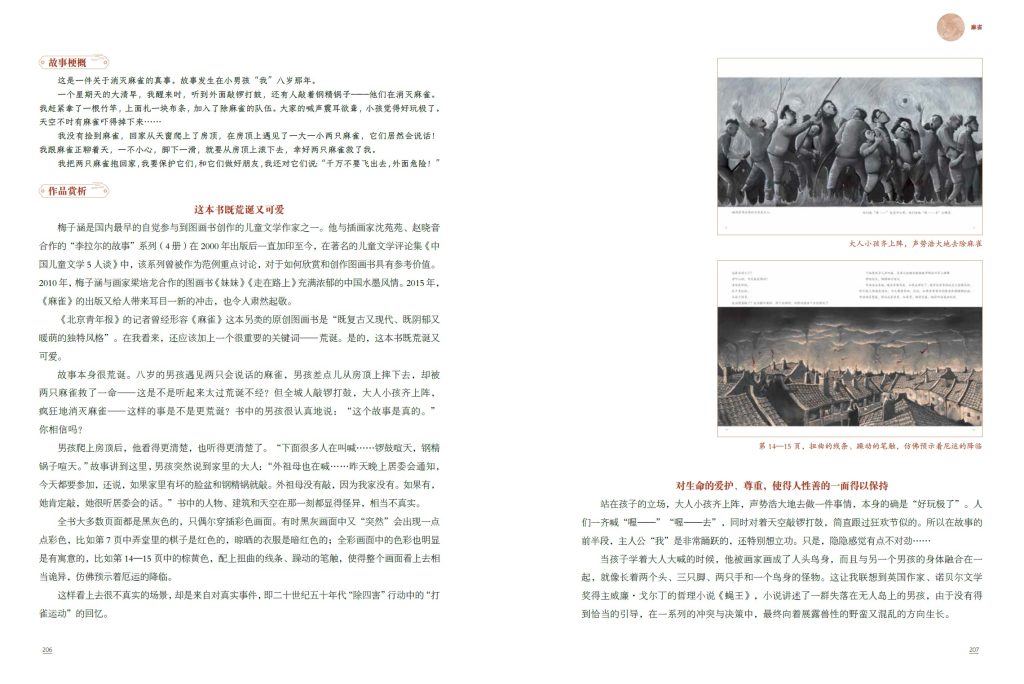

Another example is “Sparrow” by Mei Zihan, illustrated by Man Tao. I think this is Mei’s most successful picture book so far.

Although the text is quite long and basically not edited, there are some blank spaces in the original text, and many places are not fully explained, which leaves room for the narrative of the pictures. The expression of the pictures is very interesting in modern art.

I think this is a fairly successful example of “adapting famous children’s literature into picture books.”

Xiaoxiang:

Speaking of the issue of adaptation, I would also like to ask another question about the history of picture book development.

In fact, the development of originality is closely related to the personal efforts of editors and the progress of the entire industry.

So finally, could you please talk about some changes you have observed in the domestic editing and publishing industries in terms of their control over originality over the years?

Ajia:

In general, it can be said that we have entered an “era of originality”.

After so many years of learning and introducing a lot of things, we do feel that we really want to tell our own stories.

On the other hand, from the perspective of the publishing environment, there is an increasing desire to “tell good Chinese stories.” Therefore, whether from the bottom up or from the top down, everyone has a strong desire to invest more resources in original creation.

Therefore, sometimes you will see that it seems that a lot of original works are suddenly launched. No matter what the driving reason is, at least everyone is encouraging originality.

I think this is a process, and we have to accept this stage.

Of course, I will always emphasize one point:We must put original works on the world stage and not create them behind closed doors.

Over the years, I have come to believe that the most critical factor in an original picture book is not the creator, but the editor.

Creators have always been there, whether they are story writers or painters, talent has always existed.

But truly excellent and mature picture books often depend on editors. If the editor is unqualified, perhaps a good idea will be messed up or even directly ruin a good work.

Sometimes, editors even tell creators, “Just draw like others do.”

This kind of editing may very likely ruin a promising creator.

The worst thing for a creator is to imitate others from the beginning. Once you give people this impression — your creation seems to be imitating someone’s style — maybe you can still sell one or two books with this style, but you will no longer be yourself.

Everyone should have something they want to say and their own way of expressing themselves.

At present, the editorial teams of some domestic publishing houses are indeed growing gradually.

The best way to help editors grow is to let them produce successful works that satisfy them.

Only with such experience can they continue to accumulate, improve, and create more good works.

Rather than getting hung up on the details, think about how to help them create a good first book.

As long as they produce a successful work, positive feedback will come, which will encourage them to keep working hard.

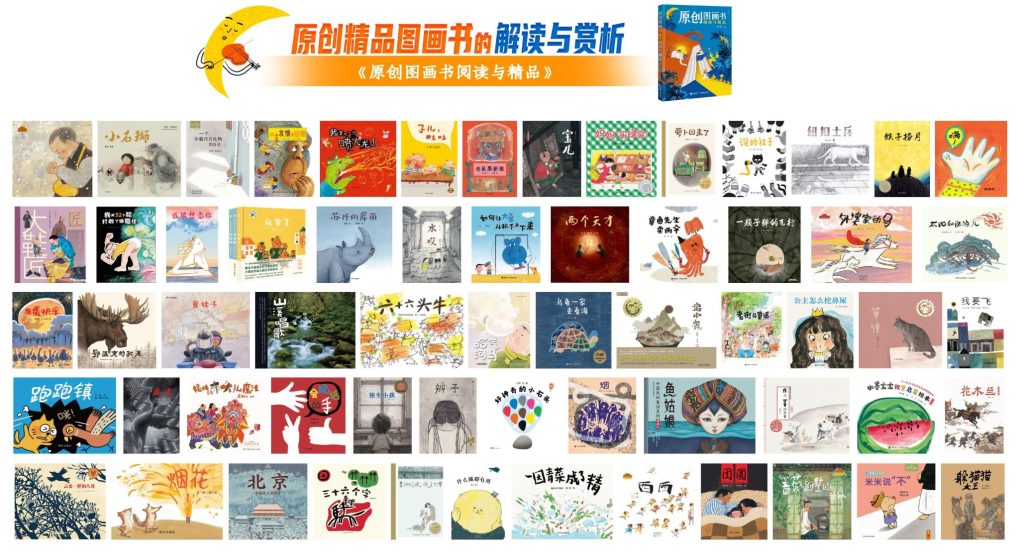

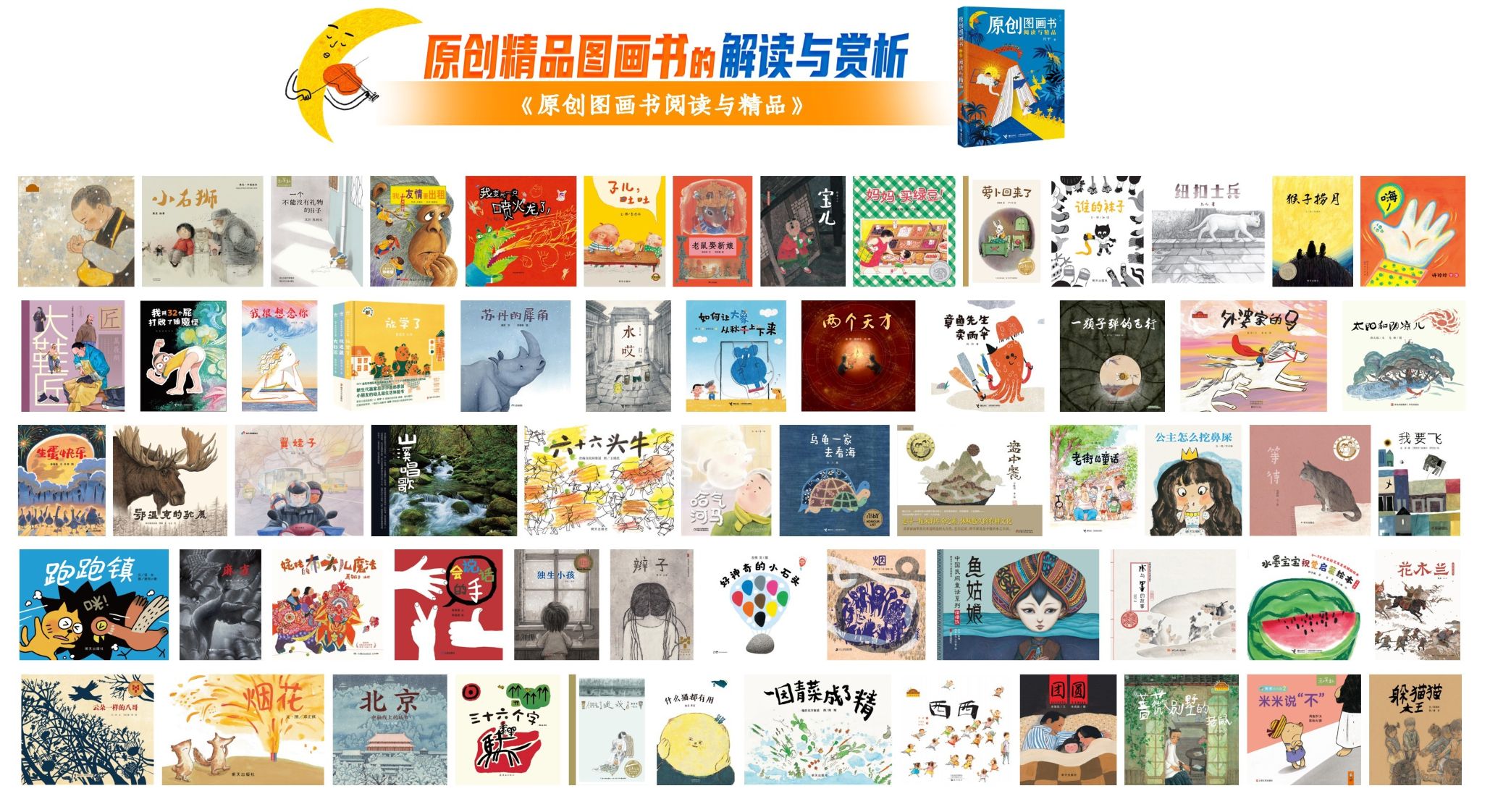

When I wrote this book, “Original Picture Books: Selected Readings and Highlights”, I actually wanted to achieve a positive feedback effect.

In recent years, I have written a lot of book reviews on original picture books, from short reviews to long reviews. In the past, I wrote more about imported works, but now I write more about original works.

I know that some works may still have shortcomings, and may not be as good as some classic imported picture books, but I hope that everyone can see their advantages, appreciate their successful side, and give some positive feedback, so that creators may do better and better.

This is the basic starting point for me to write this book.

I also think that readers can actually do more. If you see something good, be bold and praise it.

“I was deeply moved after reading this book!”

“This page is so well drawn!”

“This is a brilliant treatment!”

In this way, creators will know which efforts have elicited positive responses from readers or critics, so they will continue on this path or even go further in future works.

In general, more and more good books have been published in recent years, and some editors of original picture books have really grown up. This makes me particularly happy. As long as they can persist in doing so, as long as the market continues to give them opportunities…

But it would be a shame if any of them changed careers.

The excellent editors we have cultivated with great difficulty must be protected.

Not only creators, but editors also need protection.

On the one hand, readers of original picture books need more encouragement, and on the other hand, they also need more positive communication and feedback.

Even if it is criticism, it must be constructive criticism:

“Could this place be better?”

Rather than: “This book is absolute trash.”

That kind of criticism is worthless, right?

Xiaoxiang:

In fact, as a media person, I also truly feel that our readers are very welcoming to original picture books.

Before recording the podcast, I did some statistics. For example, we have recommended more than 50 original picture books on Lollipop’s new book list in recent years.

We have talked for a long time today. Thank you very much, Mr. Ajia!

I also especially recommend everyone to read Teacher Ajia’s “Original Picture Books: Selected Readings and Highlights”, which is really a great book!

So let’s stop here for today.

Ajia:

Thank you! Thank you Xiaoxiang! Thank you everyone!

(The above is the fourth part, the full text is over)