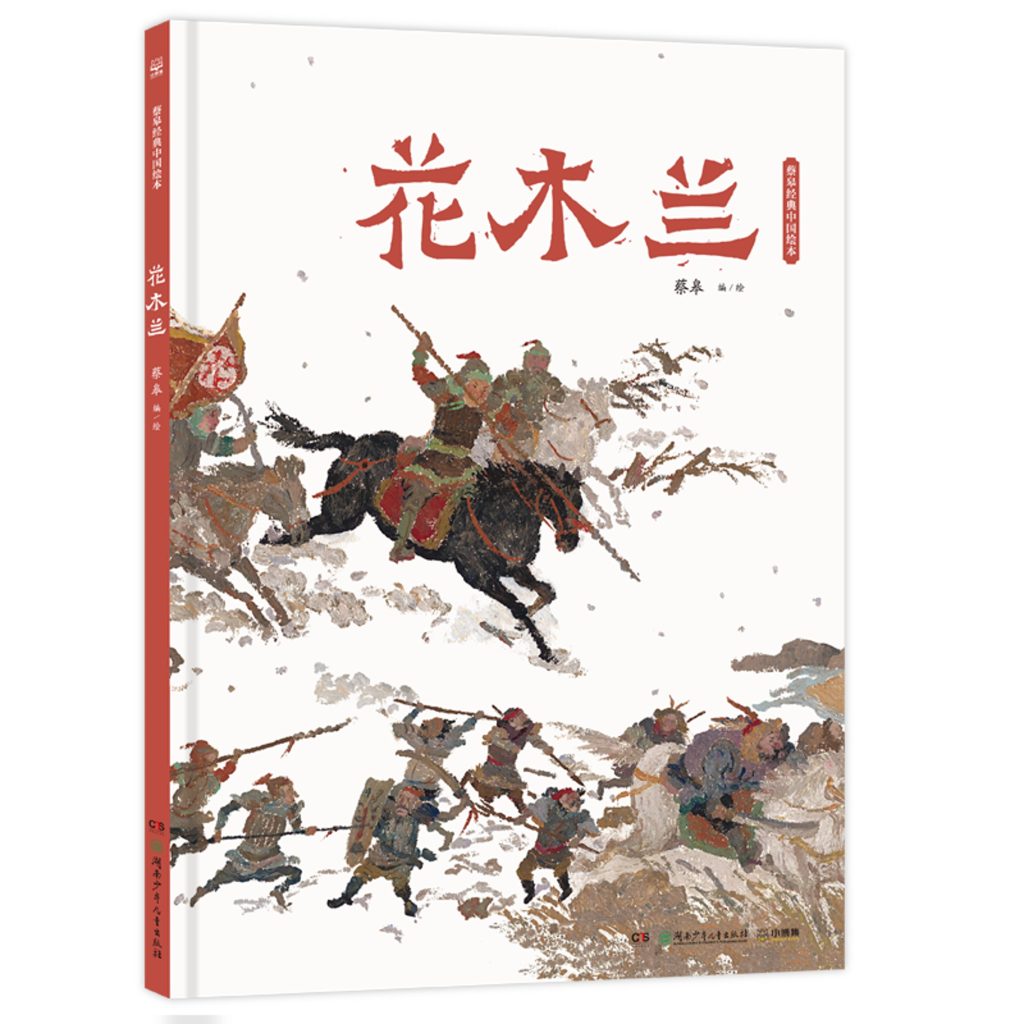

As early as 2012, two years before the initial version of “Mulan” was published, I had the honor of listening to Teacher Cai Gao’s detailed introduction to the main content and creative ideas of the book. I was very excited at the time and promised Teacher Cai Gao that after the book was published, I would sing “Mulan Ci” for her in its entirety, because this Northern Dynasty folk song is really a song that can be sung, and this version happens to strictly use the original poem as the text, with text and pictures complementing each other.

The story of Hua Mulan has seen numerous contemporary adaptations. Not only have Chinese films been produced, but Disney alone has produced both an animated film and a live-action film. In recent years, multiple picture book versions of the story have also emerged, most notably “I Am Hua Mulan,” a collaboration between Qin Wenjun and Yu Rong, and the French version of “Mulan,” a collaboration between Ye Junliang and Clémence Polet. In both film and picture book adaptations, the authors have focused on infusing this ancient heroine with modern elements, striving to explore a feminine consciousness more relevant to today. Comparatively, Cai Gao’s version of “Mulan” is the most authentic, attempting to return to a more rural and folk context, allowing for a lasting experience of the heroine’s song.

Cai Gao’s paintings blend the charm of traditional literati painting, folk painting, and naive children’s art, while masterfully employing the narrative language of picture books. The story begins on the front endpapers. Against the backdrop of a delicate landscape painting, what kind of story will the galloping warrior on horseback bring? Who is the spinning girl on the copyright page? What is the elderly father leaning on crutches looking at on the title page, and who is the girl peeking over? Turning to the main text, “Jiji, jiji, Mulan weaves by the window”… “The Ballad of Mulan” begins, and the painting depicts a warm family of five. The dark brown, earthy hue suggests a well-fed farming family, well-off through hard work. However, the peaceful atmosphere is interrupted by the father sharpening a sword. We know war is approaching.

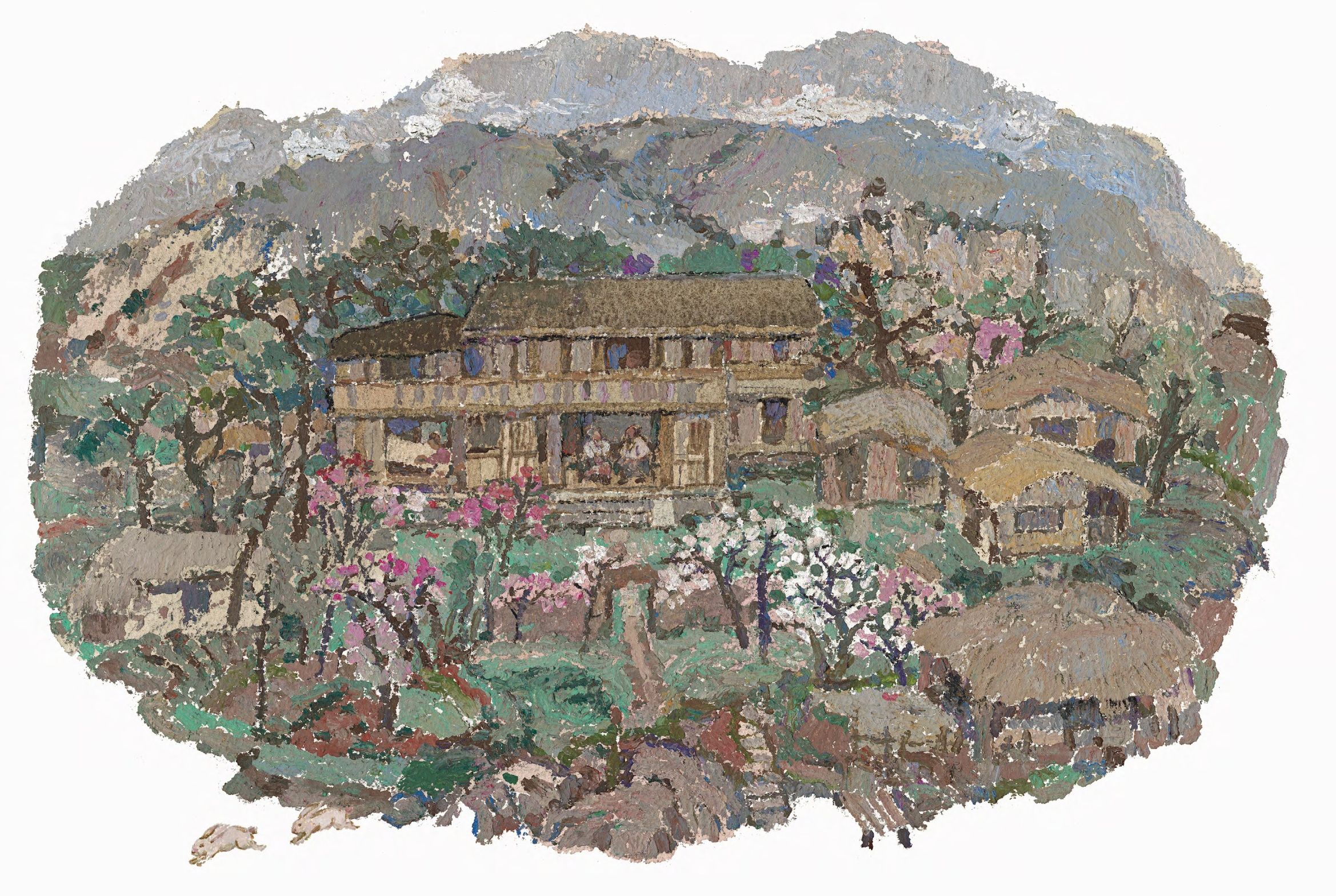

When recounting traditional stories like these, Cai Gao didn’t simply omit the depiction of the living environment. Instead, she meticulously recreates details, including farmhouses, beds, tables and chairs, farm tools, kitchens, utensils, textile looms, courtyards, flowers, plants, and trees. This ability is in part due to her years of experience teaching in rural areas and her deep love for her native land. Watching Cai Gao’s paintings of traditional stories is a profoundly enriching experience. She also meticulously recreates rural customs and practices. Mulan invites her parents to sit down when she announces her departure, and upon returning home, she bows to the elders and fellow villagers. The children naturally display an innocent and lively demeanor.

But the artist doesn’t simply stop at a realistic rendering; she excels at selecting specific objects as symbols, illuminating them with deeply symbolic meanings. For example, in the double-page painting “Morning, I Leave My Parents, and Stay by the Yellow River at Dusk,” a door appears in the lower left corner, an earthen stove in the lower center, and a well in the center-left. Scattered across the canvas are bare trees—the door, well, stove, and family tree—all symbols of home. Here, they correspond to the gathering troops heading off, creating a poignant scene of “chariots rumbling, horses neighing, and travelers with bows and arrows at their waists.” This echoes the scene of Mulan’s return home, where we see the well again. The peach tree beside it is in bloom, its petals falling in a shower of colors, their petals scattering down upon the people. This seems to symbolize recovery and hope, but the majority of people in the village are either elderly or children, which reveals the heavy price paid for this peace.

My favorite scenes are the two facing pages depicting Mulan changing her clothes in her boudoir. They both employ a technique of simultaneous interpretation, combining several events occurring at different times into a single scene. In the first, after “last night I saw the military order, the Khan was recruiting soldiers,” and thinking of her father and younger brother, who couldn’t join the army, Mulan resolutely dons her battle robes. Later, upon returning home, she “sheds my wartime robes and dons my old clothes.” While the layout of the scenes remains the same, the details differ greatly, requiring the reader to compare them like a game of “spot the differences.” This process begins with a sense of depression and ends with a sense of optimism, culminating in the next page, where she goes out to see her companions, where the emotions reach a climax.

Cai Gao’s version of Mulan doesn’t specifically explore modern female subjectivity, but it strives to restore a certain kind of life scene that remains real and tangible to this day, showcasing the role model of self-respect and self-reliance that has existed since ancient times. In this sense, it is also contemporary.

At the end of this heroic song, “Two rabbits run side by side on the ground, how can I tell which is male and which is female?” The spot where the rabbits frolic looks quite familiar. It could be a corner of Hua Mulan’s village, or perhaps the Peach Blossom Spring. If you doubt it, take a look at the endpapers. Isn’t the small bridge in the center a re-enactment of the scene where “they were startled to see the fisherman”? In fact, the Peach Blossom Spring appears in many of Cai Gao’s traditional picture books. Such a peaceful and beautiful life must have been Hua Mulan’s ideal.

Written in Beijing on January 24, 2021