Introduction: This is an interview podcast conducted on “Picture Book Lollipop”, hosted by Xiaoxiang and guest Ajia. Starting from the reference book “Original Picture Books: Selected Readings and Highlights” published at the end of 2024, an in-depth conversation was held around the selection criteria, historical context, current themes and future development of original picture books. The recording time is on the evening of January 3, 2025, and the broadcast time is January 17, 2025.

The following text is compiled as an excerpt. To listen to the full podcast, please click the following audio link:

Microcosm:http://t.cn/A6uDFbvy

[Part 2]

…

So I had a basic idea at that time: if we were to write the first book on the compilation of original picture books, we must not miss those basic books.

This was my initial starting point.

Xiaoxiang:

Was the process of drafting your list of 62 books quick? Or did you actually think about it for a long time?

Among these 62 books, which one or which ones do you think are the most difficult to choose? And which ones can you decide very quickly and feel that “this is a must-have”? Can you give some examples?

Ajia:

We probably started this in 2021. The timeline I recorded started in April 2021. When I was sure I was going to do it, I actually had a list in my mind because I had been preparing for it over the years.

But I still have to convince everyone, I need a good reason. I certainly don’t say that I have already decided “these are the books”, but I have an idea why I chose these books. This idea can actually be traced back to 2005 to 2006, when it was already in its infancy.

Why do I say so?

If we want to make a basic book list, we must have a perspective that is recognized by the public, authoritative recognition, or public recognition, and also have a certain degree of credibility.

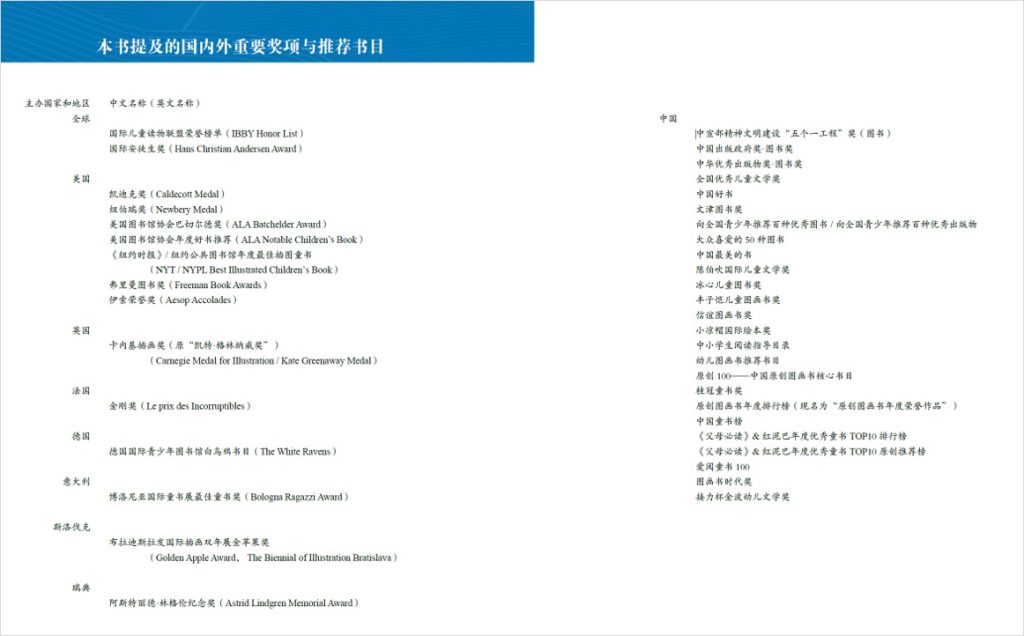

You know, when Professor Peng Yi was working on the book “World Picture Book Reading and Classics”, he actually did a very important basic work, which was to look up the awards these classic works have won in history. For example, this writer won the International Hans Christian Andersen Award, that book won the Caldecott Gold Medal, the Greenaway Medal, or other important awards. If a work has so many awards, its “classicism” is usually more guaranteed, right?

Another important reference is the best-selling data over the years. For example, The Cat That Lived a Million Times has sold two million copies or more. This is something that cannot be avoided, right?

In short, data such as awards and sales volume is a very important reference dimension.

At that time, because many of the books selected by Peng Yi were in English, I basically helped to look up the award information. I also did something very characteristic of a “legal person” at that time — because I am quite strong in science. The starting point of doing this was to make a database. In 2005, I compiled a database of the winners of the world (especially the United States) picture book awards over the years. I would check every book in the database. If a book has won enough awards, then its classic status cannot be ignored. This is the most objective basis.

Of course, there are some books that may not have won any particularly big awards, but have been repeatedly cited or mentioned in many research papers and monographs, so they should also be regarded as “natural classics.”

Another basis is the huge sales volume.

So based on this idea, when we were working on the book “Original Picture Book: Selected Readings and Highlights”, we also did a similar thing — it took us nearly half a year to sort out the bibliography.

Because we had to convince each other, and I had to convince the editorial team. At that time, Mr. Bai even considered whether to hold a meeting and invite some authoritative people to discuss it. Later, this meeting did not take place. I am not particularly clear about the specific reasons. But a very important point is: the more people participate, the more complicated the perspectives, and the more things you have to weigh.

In the end, I still stuck to my basic starting point: since this is the first time to do such a basic work, we will first use objective data as the standard.

At the end of this book, we actually list some of the awards that we focused on. If you are interested, you can take a look. Including the Feng Zikai Award, the Xinyi Award, and many other different awards. We try not to miss important works in these awards. If a book does not win these awards, but we still decide to include it, it is because it has some special features.

For example, there are unique ways of expression. We actually had a book written, called “Penguin Ice Book”, and its printing material was very special. But in the end, due to licensing reasons, we were unable to obtain the copyright, so we had to give up.

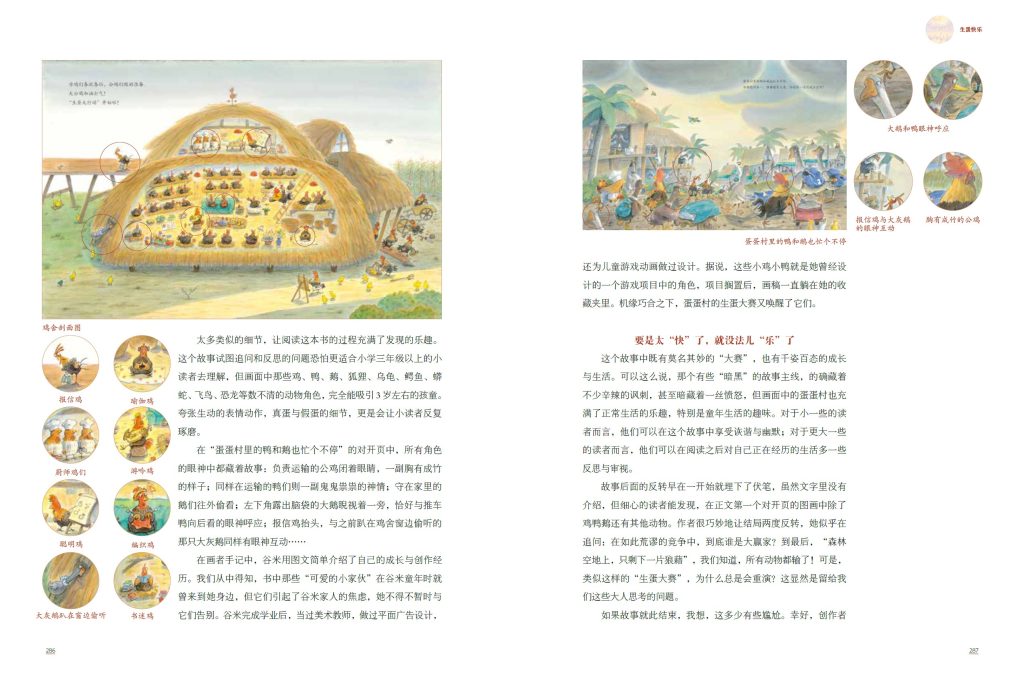

There are also some books that have not won any big awards, but I think it is very necessary to include them. For example, “Happy Eggs” is special in that it tells a story based on real events in a very child-friendly way. Although it did not win any big awards, I am still willing to include it.

Of course, this is an individual case. Most of the selected works have won important awards at least at home and abroad.

China’s current award system for original picture books has basically been gradually established since 2015. It would be a pity if even these award-winning works were not included.

There are also those who are recognized as important creators, especially those who have made significant contributions to the development of original picture books, such as teachers Xiong Liang, Cai Gao, and Zhu Chengliang. Their works should be included at least two books. But you will find that even if two books are included, it is still not enough to reflect their real contributions.

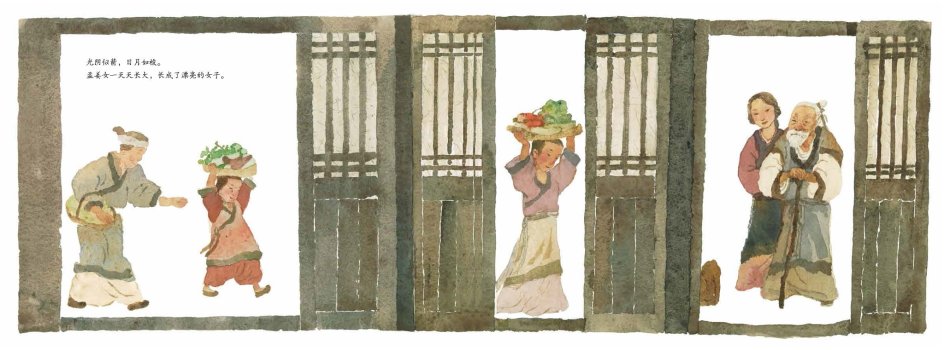

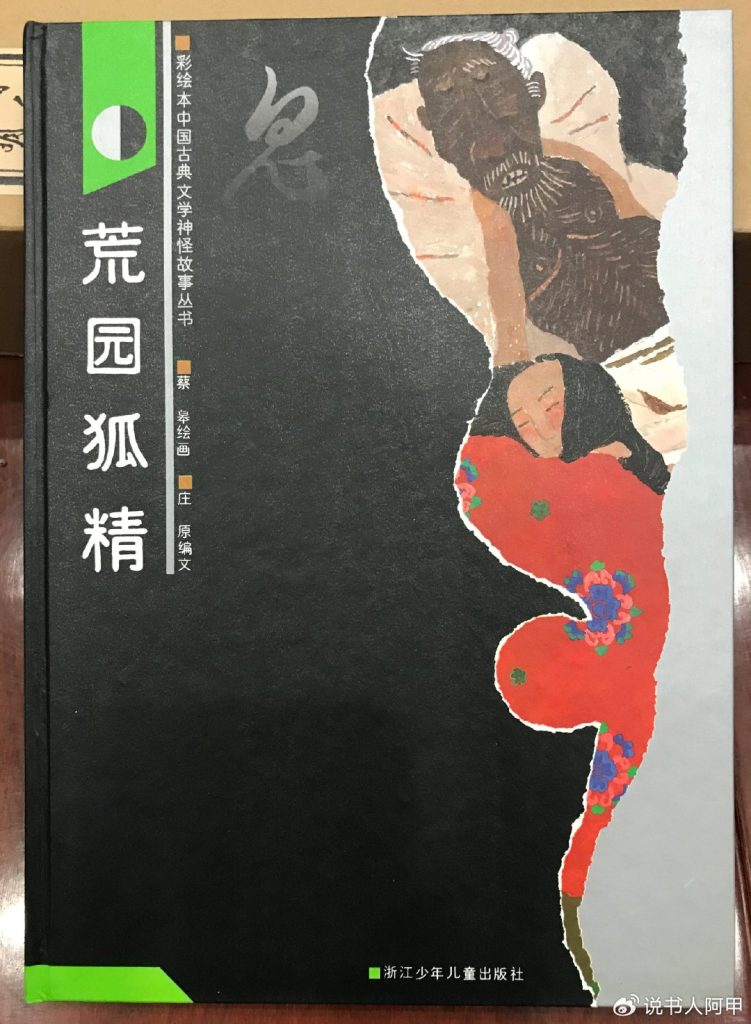

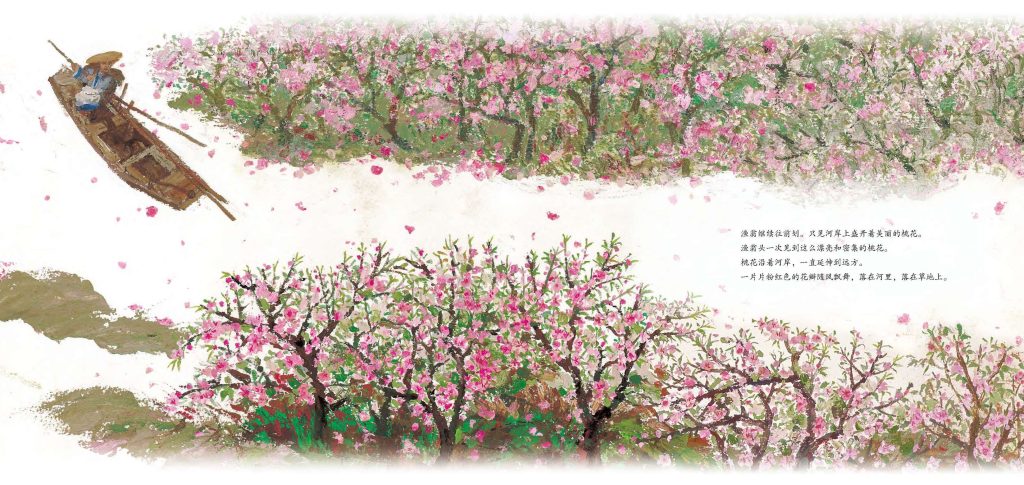

For example, I couldn’t include “The Story of Peach Blossom Spring” because it was originally published in Japan. There are also many other excellent books by Teacher Cai Gao, including “Meng Jiangnu Crying at the Great Wall”, which I like very much, but I didn’t include it. This is a great regret for me.

But in general, it is still a balance in the end. We have established some basic principles, such as no more than two works per creator, which is a bottom line — after all, this is the first time we have done this kind of work.

Xiaoxiang:

You just mentioned Cai Gao’s “The Story of Peach Blossom Spring”, so I would like to ask a related question. In the beginning of your book, you actually talked about the definition of “original picture books”. I think we can talk about this concept.

Because different people have different understandings of the so-called “original picture book”, and I think your definition in the book is very clear.

But I still have some questions and would like to ask you.

For example, you mentioned that if a book is created by a Chinese, even if it is first published abroad, you actually include it in the scope of this book. In your definition of this book, original picture books include such situations.

But in my understanding, if it is not edited and published by a Chinese publisher, it seems that it is difficult to be considered an “original picture book.” Although it is created by Chinese people, this matter itself seems to be more complicated.

So why do you think they should be included?

Ajia:

This is actually a question of “leniency” or “strictness”.

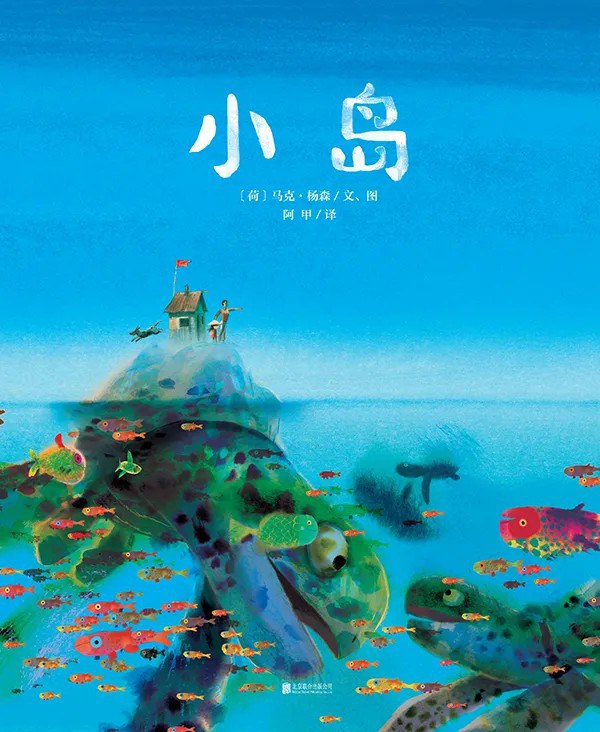

If you define originality purely based on the place of publication — in fact, for example, Mark Janssen’s “Little Island” was published entirely in China, but no one has ever regarded it as an original Chinese picture book, right?

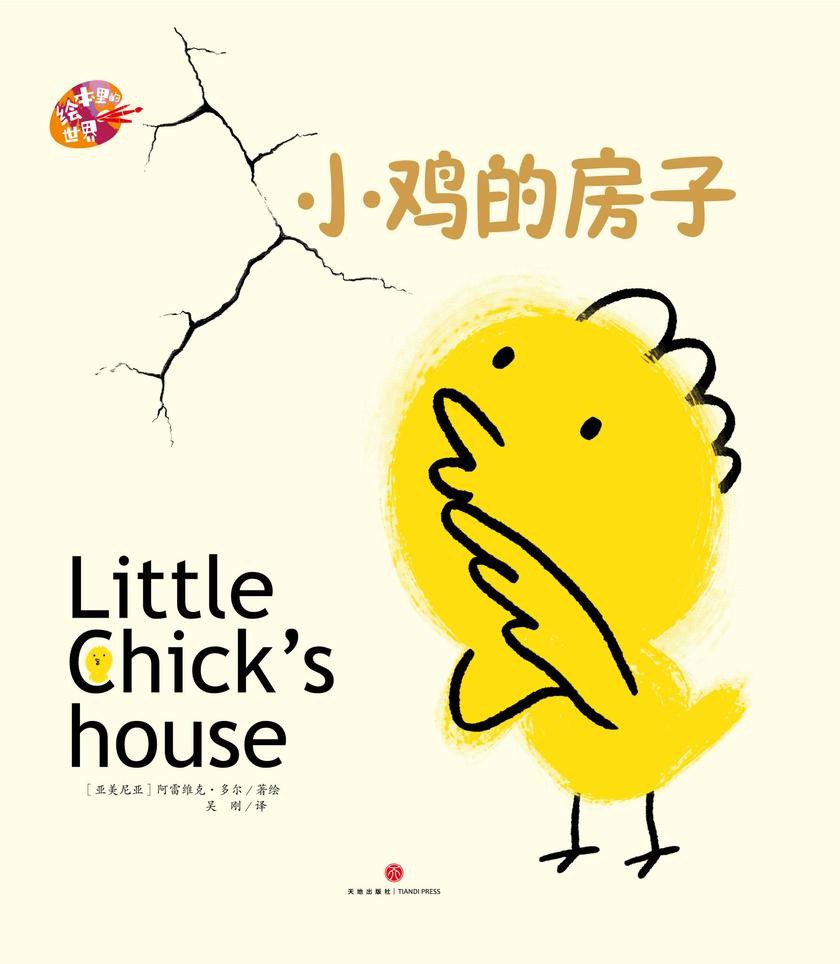

For example, “Little Chicken House” (Arevik Dol [Armenia]) is such a good book, but it will not be considered as an original picture book in any award selection I participated in.

But the problem is that they were indeed edited and published in China for the first time, and have never been published abroad. So why don’t we regard them as original picture books?

This is a very interesting question. In fact, we Chinese have a more complicated understanding of the concept of “originality”.

In the past, there was a technical definition that any copyrighted book that was “introduced under a contract” could not be considered an original picture book. This is the rule in some originality award selections.

But I tell you, “Xinyi original picture books” may actually be “imported” — because they are first registered in Taiwan and then published in mainland China. Does that mean that all Xinyi’s “original picture books” are not original? Do you think this is reasonable?

We have been saying that “Taiwan is an inalienable part of China”!

Therefore, sometimes it is rather embarrassing to discuss the issue of “originality” in China, and it is easy to get caught up in some messy arguments if you are not careful.

My own understanding is this. Because I studied law, you will see that I defined “original picture books” in the first part of this book.

What is this? It is the “constitution” of this book, the fundamental law. I will first make the standard clear. You may disagree, and you may write a paper to criticize or oppose my definition, but I will not be ambiguous or evasive. I will clearly tell you how I define it and why I define it that way.

If you have your own definition system, that’s great too. You might as well write a book to explain your point of view — I would welcome that!

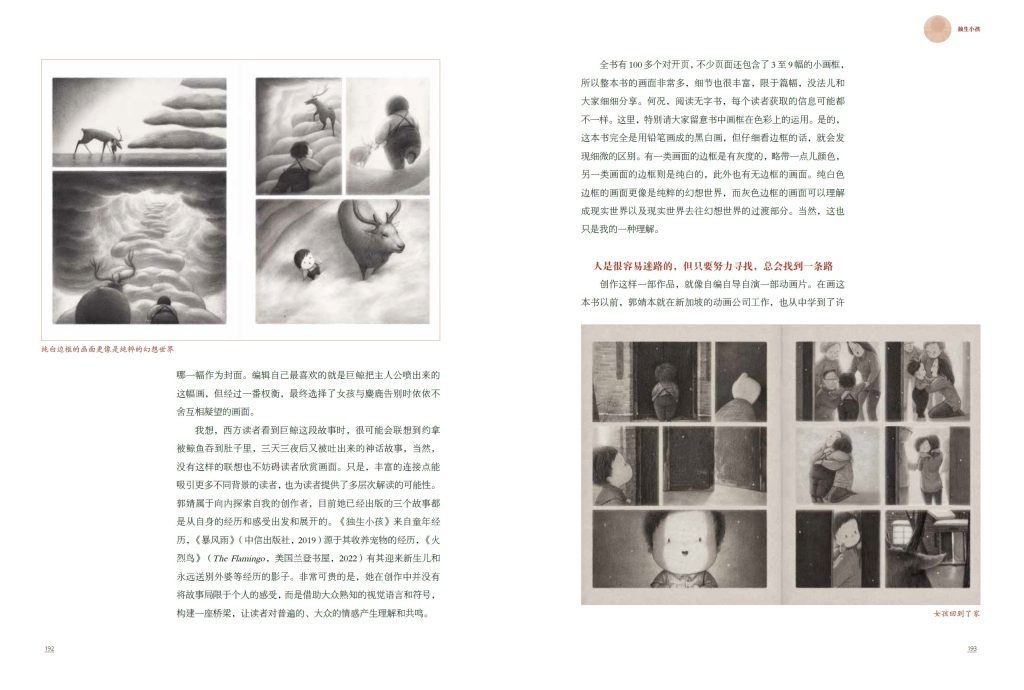

To be honest, this way of defining is also a “Chinese characteristic”. Let me give you the simplest example. Guo Jing’s “Only Child” was first published in the United States. Why in the United States? Because there is no publisher in China, it’s that simple. What story did she write? It describes the state and state of mind of the only children of our generation born in the 1980s. Where is the background of the story? In Taiyuan, where Guo Jing lived in the 1980s.

You said, if such a book cannot be called “original”, then what is “original”? And she completed her creation in Taiyuan.

In the past, we had to publish many books overseas. For example, Baoer, formerly known as Fox Spirit in the Wild Garden, was published as Baoer in Taiwan. At that time, the publishing environment for our picture books was not very mature. The version of Nezha Conquers the Dragon King by Yu Dawu, which won the Japanese Grand Prize, was also published in Japan first.

“The Story of Peach Blossom Spring” — If we can’t even consider a book like this original, then how unfortunate is that?

So I listed three key elements in the book: author, illustrator, and place of publication. I think as long as one of them is from mainland China, I will include the book.

Of course, there are some books that can be considered “Chinese originals”, such as “The Island” and “The Chicken House”. From the principle of territoriality, they are both Chinese originals. But they do not have particularly obvious “Chinese characteristics” in their content. So I think they can be introduced later. I have many other books on hand that I can talk about first.

This is a “technical treatment”: I will not introduce this type of work for the time being. In the future, perhaps I can write a book to introduce those “foreign works published in China for the first time.”

Xiaoxiang:

This is also a very interesting little topic.

My next question is about the time definition of the books in your “Next Part: Excellent Original Picture Books”.

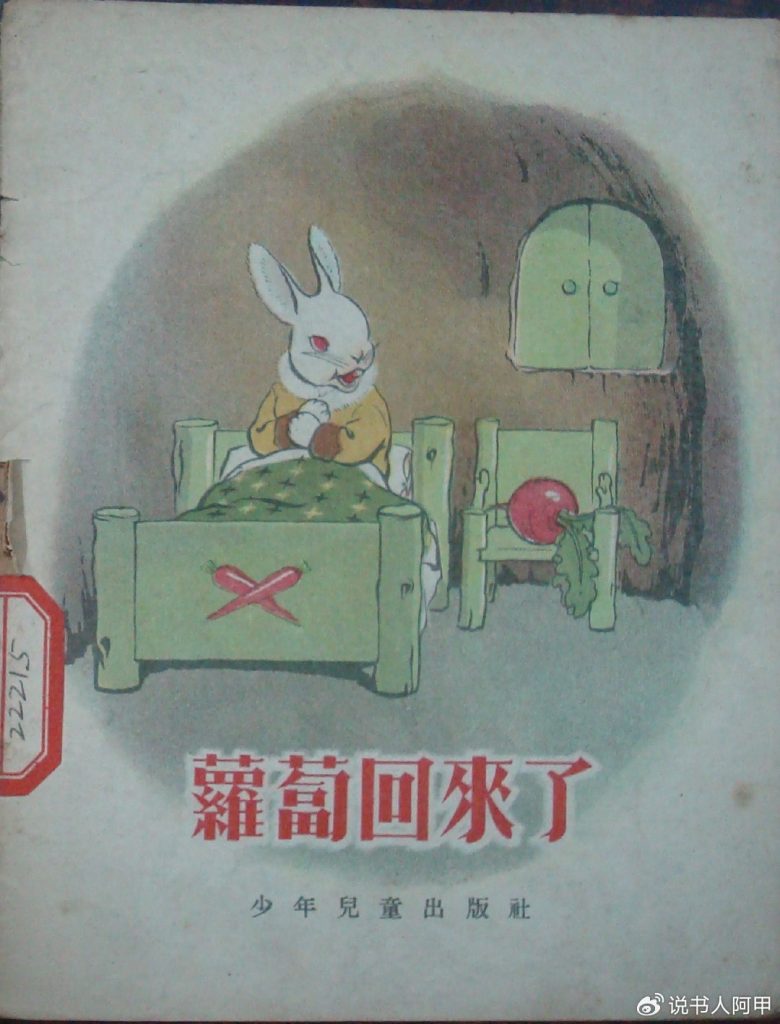

What impressed me most was that the first book was The Carrot is Back, published in 1955, which is the one written by Fang Yiqun. The second book was Mom, Buy Green Beans, published in 1988.

At that time, I felt really emotional: Oh my God, it took more than 30 years to get to the second book!

If The Return of Radish can be regarded as the starting point of contemporary Chinese original picture books, then it has been more than 30 years since the first one. Have we run out of books in these 30 years?

Speaking of the first book “The Return of Radish”, was there no original picture book that met your definition before it?

Ajia:

This is actually a question that is both complex and simple.

Strictly speaking, if we look at the time point, the one published in 1955 is indeed a picture book originally published in mainland China. Of the second one, only “Bao Er” is actually a mainland original work, but its original version was “Hu Jing in the Wild Garden”, which was published in 1991.

The next book created and published by a mainland Chinese creator was actually Little Stone Lion in 2005. However, Little Stone Lion was also originally published in Taiwan.

So you see, from 1988 to 2005, the works included in my book were basically published in Taiwan first. Even “The Fox Spirit in the Wild Garden” was published under the name “Bao Er”, which was first published in Taiwan and then republished in mainland China.

This phenomenon is really very Chinese.

So why did I choose this?

I once explained at a press conference that this book is mainly about original picture books from mainland China since 2000, because the history before 2000 is actually quite complicated.

“The Return of Radish” from 1955 is mainly used here as a symbolic representative to illustrate that before 2000, we actually had original picture books.

But I did not elaborate on this part. In “Part 1: Reading Original Picture Books”, I wrote about some historical developments and mentioned many original picture books published before 2000. But in “Part 2: Fine Original Picture Books”, I chose to leave this section completely blank, and I wanted to leave it to Teacher Wang Zhigeng to write.

Every time I see him, I have to “urge him to finish the manuscript” (laughs), because I think he has to write a book like this.

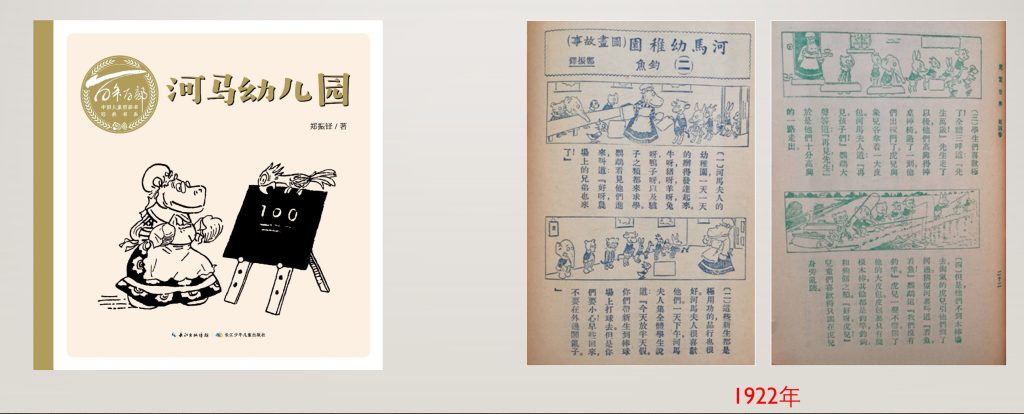

He has a very rich accumulation of information. During his tenure as the head of the National Library’s Collection and Children’s Library, he had already started a lot of solid work. He also took the lead in planning a series of books called “100 Years of 100 Classic Chinese Children’s Picture Books”. The earliest book in this series is “Hippo Kindergarten” published in 1923. In fact, there are indeed some picture books from the Republic of China period that can be reproduced.

But before 2000, the most influential book, the one whose prototype can still be seen today, was The Return of Radish, published in 1955. There are more than 40 versions of this book in the world, and some of them are selling very well. It has become a world-class phenomenon.

Everyone thinks that this book is a long-standing folk tale, but in fact it is an original work by a Chinese writer in 1955, and it is adapted from a story in the Battle of Shangganling during The Korean War.

(The above is the second part, to be continued)