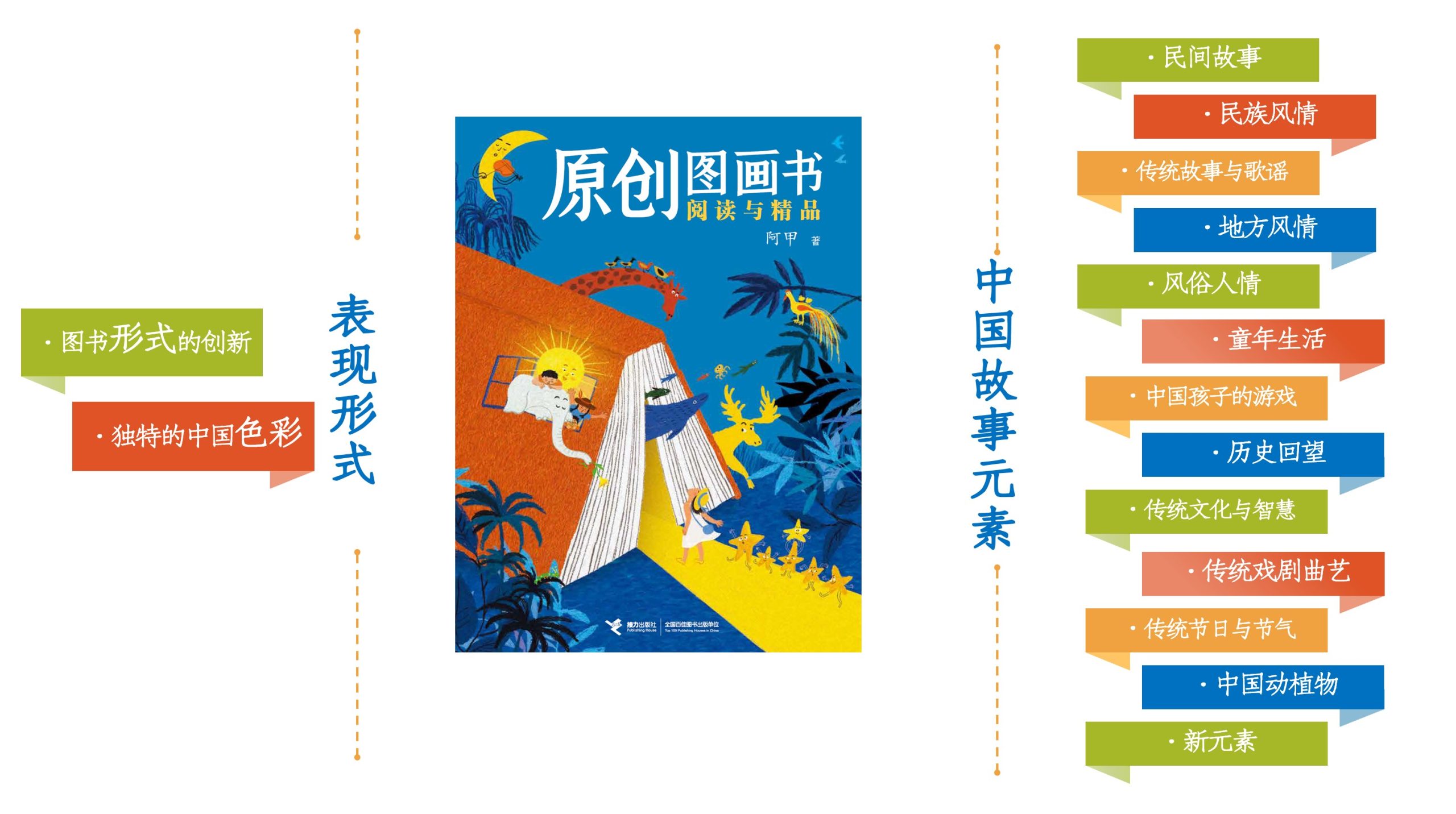

Introduction: This is an interview podcast conducted on “Picture Book Lollipop”, hosted by Xiaoxiang and guest Ajia. Starting from the reference book “Original Picture Books: Selected Readings and Highlights” published at the end of 2024, an in-depth conversation was held around the selection criteria, historical context, current themes and future development of original picture books. The recording time is on the evening of January 3, 2025, and the broadcast time is January 17, 2025.

The following text is compiled as an excerpt. To listen to the full podcast, please click the following audio link:

Microcosm:http://t.cn/A6uDFbvy

Click to open »> Part I | Part 2

Part 3

…

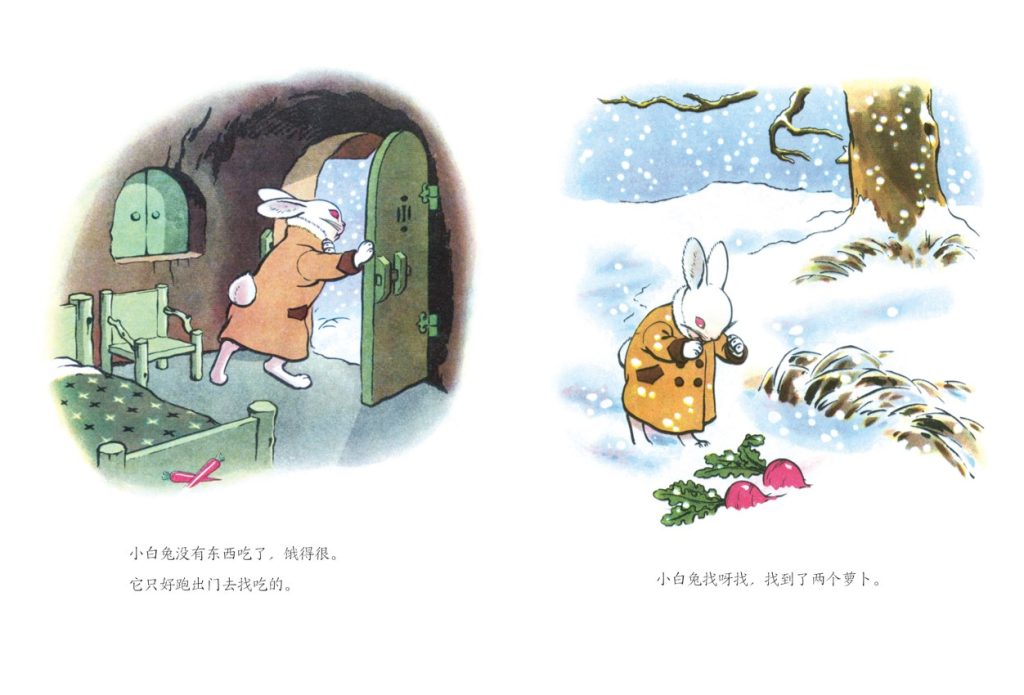

Everyone thinks that this book (The Return of Radish) is a long-standing folk tale, but in fact it is an original work by a Chinese writer in 1955, and it is adapted from a story in the Battle of Shangganling during The Korean War.

Xiaoxiang:

Yes, I also learned about this after reading your book. It’s really amazing!

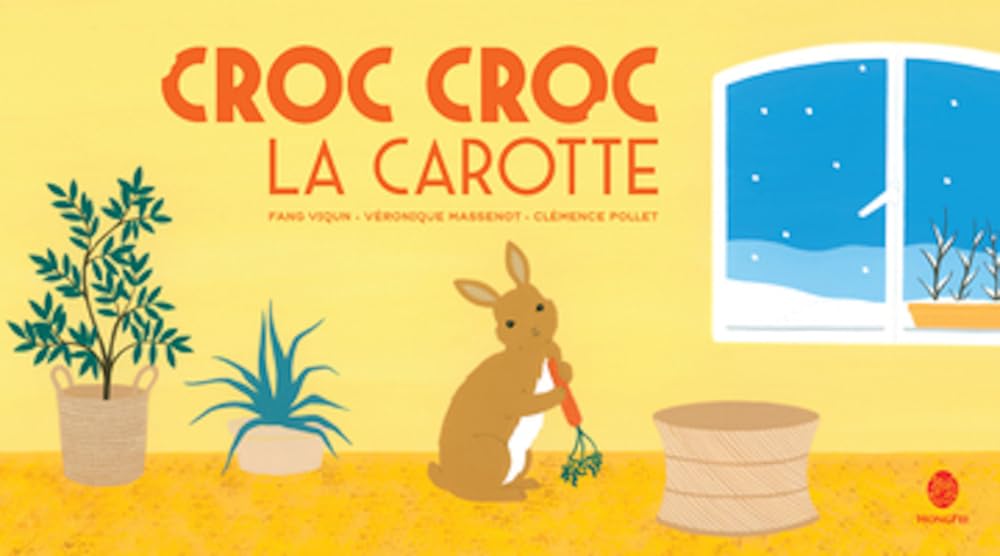

I also remember that at the Shanghai Children’s Book Fair last year, I interviewed Mr. Ye Junliang from the French Hongfei Publishing House. He mentioned that they also published this book “The Return of Radish” in France, and the illustrator was the French girl Clemence Pollet who drew the French version of “Mulan”. Her illustrations are very consistent with the contemporary aesthetic style. So I think this story is really magical.

Then I think we can talk about some further topics.

For example, in the first part of your book, after introducing the definition and development of original picture books, you spent a lot of space talking about the characteristics of original picture books. I think this area is particularly worth exploring in depth. You put forward some keywords, such as “unique colors”, “Chinese story elements”, “local customs”, “traditional culture”, “philosophical thoughts”, etc.

I would like to ask you to talk about this part. You mentioned at the beginning that Chinese original picture books have a special “color”. In fact, we didn’t seem to pay much attention to this before.

You also specifically mentioned in your book that the use of colors in original Chinese picture books actually has two cultural sources: one is literati ink painting, which is relatively fresh and elegant, with a literati temperament; the other is the lively, folk color expression.

Could you please elaborate on this topic? It is about the use of colors in original Chinese picture books and the cultural origins reflected by these colors.

Ajia:

This is a good question. But I would like to say a few more words about the topic that I did not fully discuss before.

Why did my book end in 2000? The part before that, including the color you mentioned, may be immediately clear if you know picture books before 2000. I did not expand on this part because the information is not sufficient. But the “100 Years, 100 Books” series mentioned above, in fact, many are reprints of old books collected by Teacher Wang Zhigeng.

However, for example, there are some differences between “The Return of Radish” and the first version published in 1955. For example, from the perspective of picture narrative, the reading direction was not completely from left to right. The direction of travel at that time was more random, sometimes from left to right, sometimes from right to left, for the convenience of arrangement and also considering printing costs.

You know, we now generally believe that going from left to right is forward, and going from right to left is backward, which is our common narrative grammar. But in the 1950s, these were not very important, so the new version you see now is actually a re-arrangement, not exactly the original one.

There was controversy at the time, and some editors believed that since it was a replica, it should be kept in its original state to have archival value. However, most editors still felt that some adjustments should be made to respect the reading habits and interests of contemporary and future children.

So the text and layout of the version you are seeing now have actually been modified.

But I think this is very important:

Why are we still willing to preserve and reproduce China’s early original picture books?

Because they are really beautiful, the illustrations are really beautiful.

The creators of that era often had a very deep foundation in Chinese studies and traditional art, and many of them were multi-talented. For example, Mr. Yan Gefan, the illustrator of “The Carrot is Back”, is actually a musician. His family is first-rate in animation, music, and art. It is hard to imagine now that an illustrator of a picture book can be a playwright, animation director, musician, and artist at the same time, but it was not uncommon in that era.

On the one hand, they can draw fairy tales and learn Western techniques, and on the other hand, they have a very strong foundation in traditional Chinese art. Whether they are drawing traditional stories or children’s stories, the style of their works is sometimes very elegant, with a strong literati color; sometimes they are particularly festive, integrating a lot of folk art elements.

In fact, if you study the development of Chinese contemporary art, you will find that artists like Lin Fengmian, Zao Wou-Ki and Wu Guanzhong have all drawn a lot of nourishment from Chinese folk art. They have combined contemporary art and traditional folk art very well.

The picture book illustrators who were at the forefront of the times often possessed two qualities at the same time:

They can create paintings with a very literary temperament, and can also absorb very rich folk creative resources. But they are not the kind of “copying” you see in folk paintings.

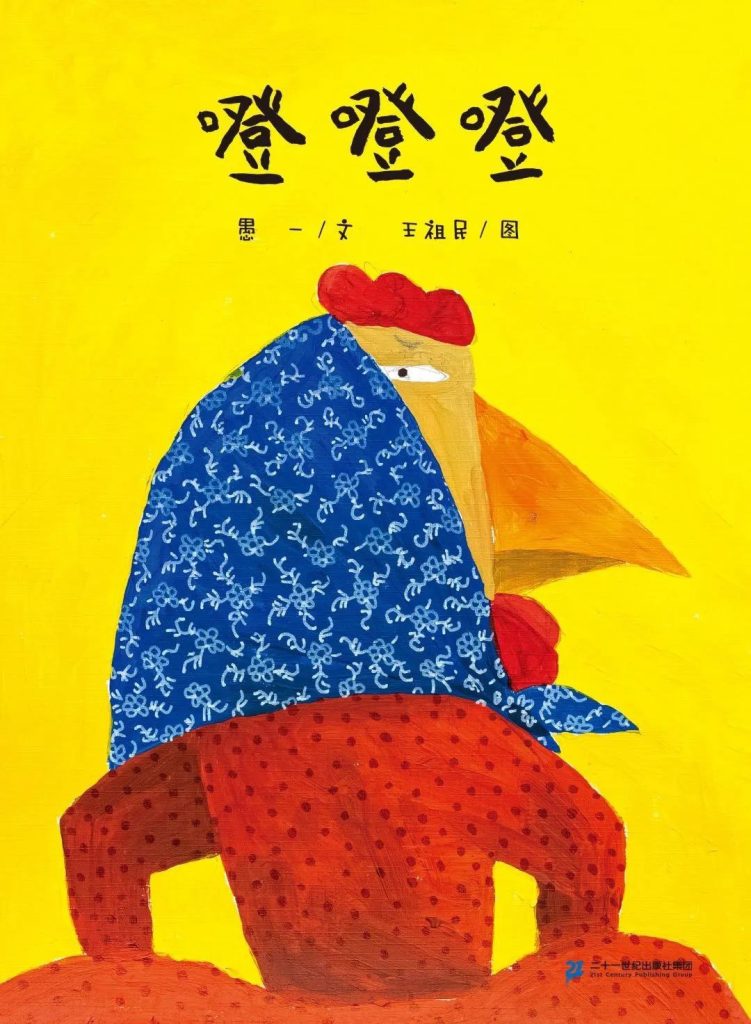

Let me give you an example. Take for example the book “Dengdengdeng” by Wang Zumin, which recently won the Bologna Illustration Award. You see, it has a folk flavor, right? But it is also a work with modern artistic interest.

Xiaoxiang:

Yes, so it won the award in Bologna. The Western judges also mentioned the “style of Western contemporary art” in their comments, which we thought was quite strange at the time.

Ajia:

Yes, but in fact you will find that it is actually an extension of the school of Lin Fengmian.

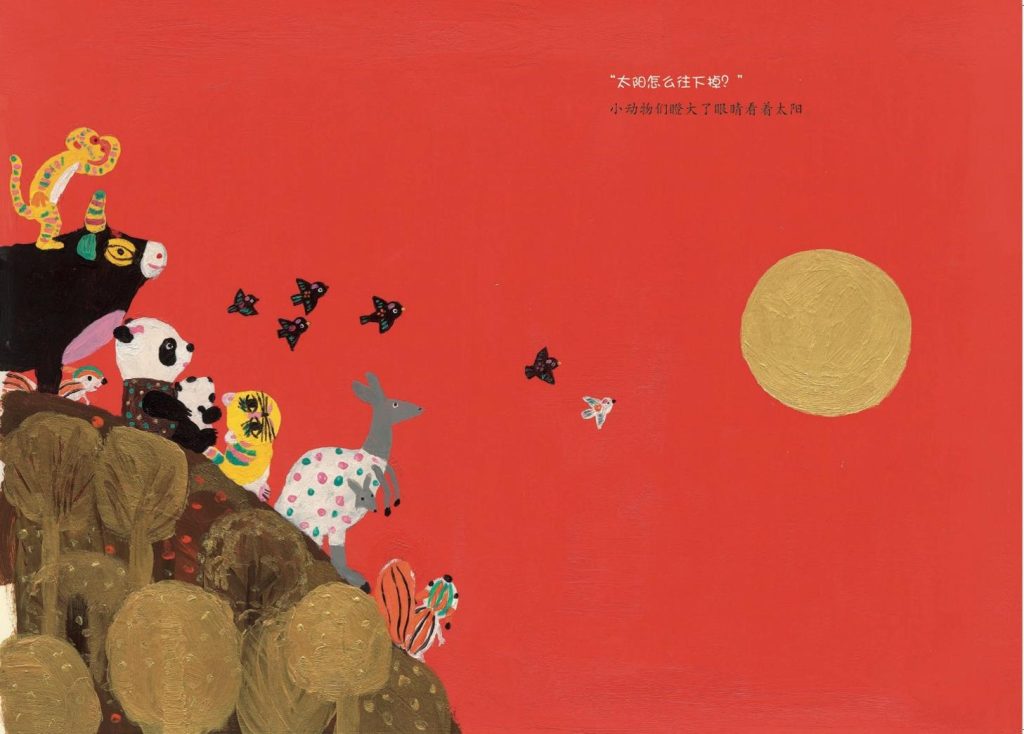

For example, Zhu Chengliang’s painting “Don’t Let the Sun Fall” looks very folk, but in fact it also incorporates the expression of contemporary art. Zhu Chengliang was the editor of “Folk Art” at the time and was deeply influenced by the editor-in-chief, Ke Ming, who was a student of Lin Fengmian.

There is also Teacher Cai Gao — on the one hand, she is good at painting very literati things, the most typical example is the blank space in “The Story of Peach Blossom Spring”, which itself has a freehand style. But if you look closely, you will find that her colors and shapes are actually also very characteristic of folk paintings.

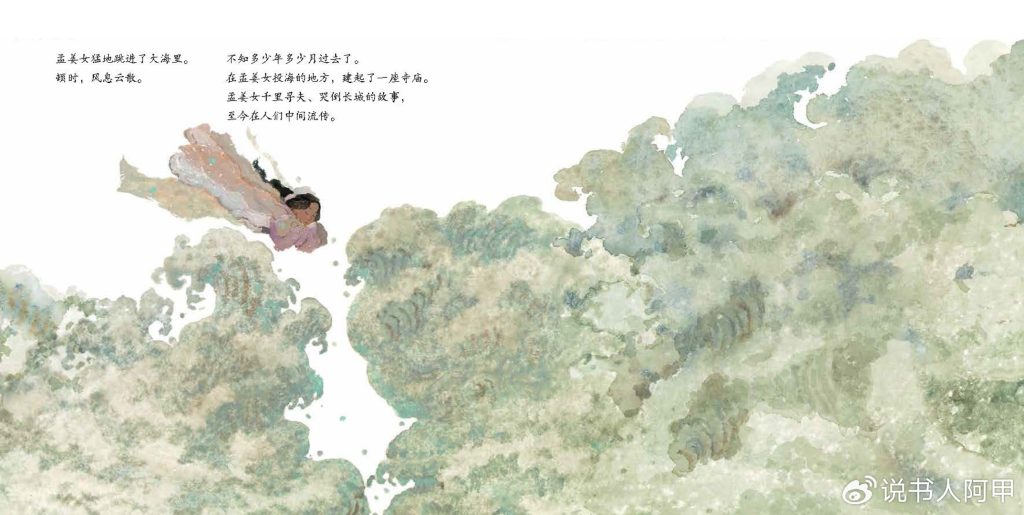

Especially her “Mulan”, that kind of beauty, that kind of taste, and the deep earthy smell, as well as the symbolic expression, I think it is very good. I personally like her “Meng Jiangnu Crying at the Great Wall”, the colors are very symbolic, it can’t be said to be purely folk, but you can really feel the folk meaning.

I would like to emphasize that the artistic characteristics of Chinese original picture books can be felt very intuitively in terms of color. You can tell at a glance that some works are Chinese.

For example, when Zhu Chengliang’s Don’t Let the Sun Fall was just published, it happened to be the Shanghai Book Fair, and I showed it to Mr. Marcus from the United States. As soon as he opened it, he said that the book looked “very Chinese”, very Chinese.

But what’s interesting is that although he couldn’t read Chinese characters, he could immediately understand what story the pictures were telling. This shows that the visual narrative of this book is actually very “Western”. To some extent, it has absorbed a lot of the fun of narrative in Western picture books.

For example, the sun rises from a certain position in the picture, moves to another position at noon, and finally sets. The change of the height of the sun in the picture shows the advancement of time — this is actually a common narrative method of time and space in Western picture books.

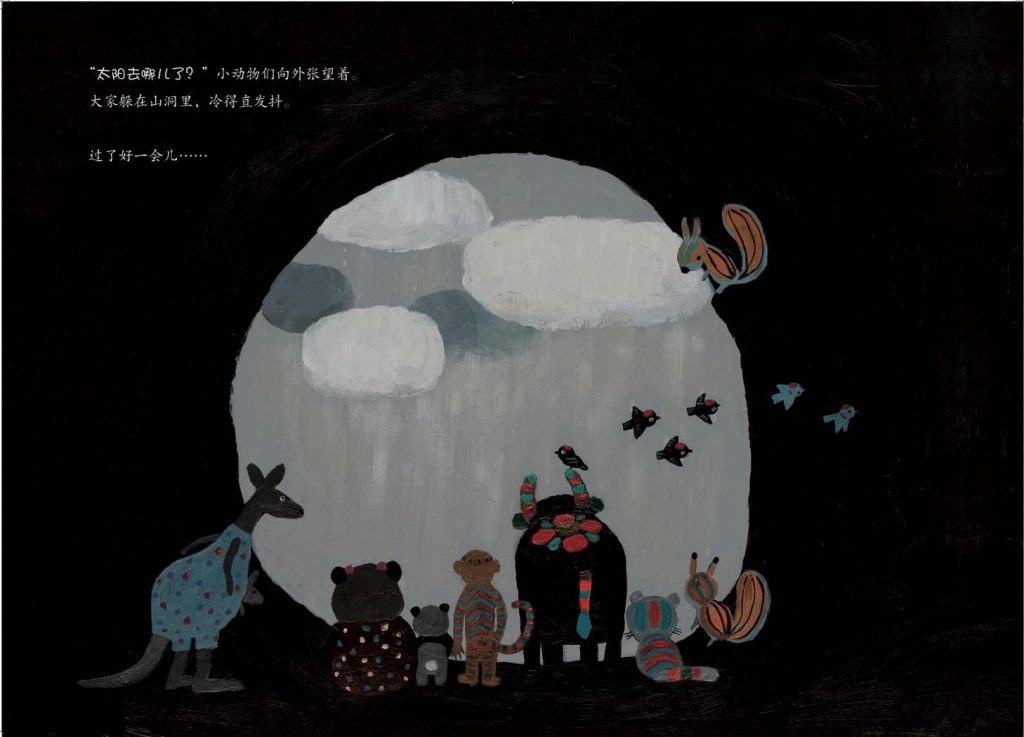

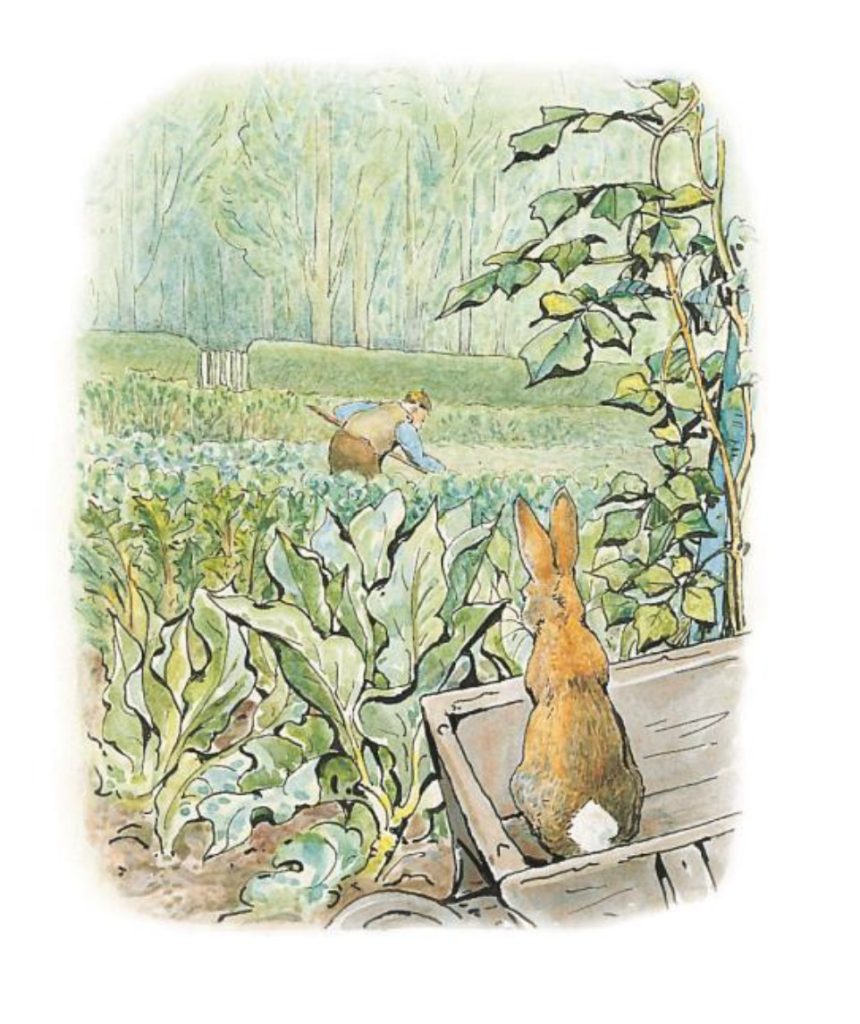

For example, there is a scene where we are standing in a cave and looking out, standing behind the animals in the story, and looking at the scenery they are looking out. This kind of “person involved perspective” actually appeared in “The Tale of Peter Rabbit”. This is not the way of expression in our traditional Chinese visual art, but the grammar of Western picture book narrative.

But its colors are completely traditional Chinese colors.

I think these creators are really amazing. They have found a very good balance between “tradition” and “modernity”, “East” and “West”.

Xiaoxiang:

Do you think that the use of colors, which is influenced by Chinese tradition — whether it is literati painting or folk art — will continue as a trend among the new generation of original picture book creators, or is there some changes taking place?

Ajia:

I think there may be a gap at some stage.

For example, I once gave a lecture in Wenzhou, sharing Cai Gao’s “Meng Jiangnu Weeping at the Great Wall”, and Tian Yu was also present at the time. When I talked about the colors of this book, he was very shocked. He didn’t expect that there was such a strong expressive intention behind those colors.

For example, the color of “water” in the book is emerald green. In the eyes of Mr. Cai Gao, it is the color of “jade”, which symbolizes the integrity and integrity of “rather be broken into pieces than live in husks”. The colors of the objects in the painting actually convey the character of the people. This is the spiritual essence of “using objects to express ideas” in our traditional literati paintings.

Tian Yu and his generation of creators may not have been particularly aware of these things at the beginning. They may not have considered the symbolic colors as the main creative elements. They are more concerned with the shape itself, and prefer styles with a bit of cartoon fun and action performance. They also have their own way of expression. This is because they grew up in another visual culture environment.

But when they truly appreciate the beauty of these traditional expressions, you will find that they are also trying some kind of fusion.

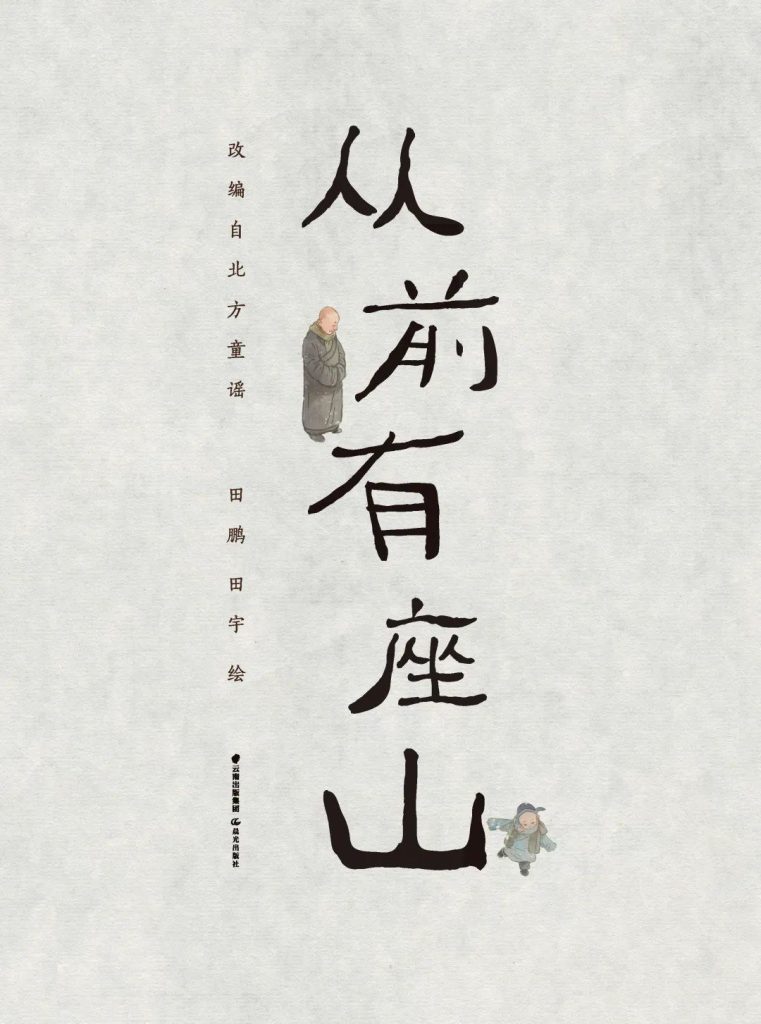

For example, Tian Yu later collaborated with his father on Once Upon a Time There Was a Mountain. You can see that the book is actually an attempt at fusion. The backgrounds in the book were painted by his father, an ink painter who particularly likes to paint traditional landscapes; the characters were mainly painted by Tian Yu. You can see that in Tian Yu’s recent creations, he has also begun to consciously explore the profound connection between color and meaning.

The act of “crossing the fault” actually requires people to “build a bridge”.

I myself am also in the process of continuous learning, slowly understanding and experiencing. After understanding, sometimes you can’t help but exclaim: “Wow, it turns out that you can express it this way, it’s amazing.”

Sometimes you just feel it but can’t say it. But as you continue to communicate and learn, you will be able to say it and express it. Others may also feel it and even begin to consciously look for such ways to express it.

You have to understand that visual language is constantly evolving. We won’t always use only one way of expression.

Moreover, some contemporary art expressions are actually found in very ancient sources. For example, a lot of contemporary art is actually inspired by cave paintings.

Therefore, we must continue to rediscover and reopen those traditional ways of expression.

Xiaoxiang:

Another topic suddenly occurred to me.

Many of the books we just talked about, especially those by the older generation of picture book creators, are adapted from folk tales or ancient classics.

As a reader born in the 1980s, I actually have some natural expectations for the fun of these adapted works. I hope that they can bring a sense of “subversion” or make me feel refreshed. If the drawings are just good and the text is just a simple retelling of the original story, then I may not be particularly interested.

So I would like to ask you:

Do you think it’s possible for our domestic original picture books to be adapted into something completely different in aesthetics and expression, like “Mulan” published by France’s Hongfei Publishing House?

In other words, will there be adapters like Mike Barnett and Jon Klassen in the United States? They have adapted many fairy tales, but each one has a strong personal style and contemporary interest. For example, the style of their adaptation of “The Three Billy Goats Gruff” is completely different.

What do you think about this issue?

Ajia:

As you said, the French version of “Mulan” is the interpretation of French creators; the live-action movie version of “Mulan” and the animated version of “Mulan” that we see are the American interpretations, right?

In fact, an old story may be reinterpreted by different people to create a completely new version.

For example, the original story of “The Laughing Old Woman Who Lost Her Rice Ball”, which won the Caldecott Gold Medal, was collected and compiled by Hearn Yakumo, a Greek-Japanese who later became a naturalized Japanese. The picture book version of the story was adapted by an American librarian.

Such spread and adaptation is actually a very natural thing.

There are also different versions of Hua Mulan in China, such as I Am Hua Mulan, a collaboration between Qin Wenjun and Yu Rong, which is a completely different story.

These are all good, so I don’t think there is any need to worry too much.

But what I want to emphasize is that when we retell a folk story, we must have our own ideas. We must think about what we want to say to the children of today and the children of the future. This is very important, right?

For example, the song “Once Upon a Time There Was a Mountain” by Tian Yu that I mentioned earlier is actually different from the nursery rhyme we sang when we were young, “There is a temple in the mountain, there is an old monk in the temple…” It tells more of a story about family affection.

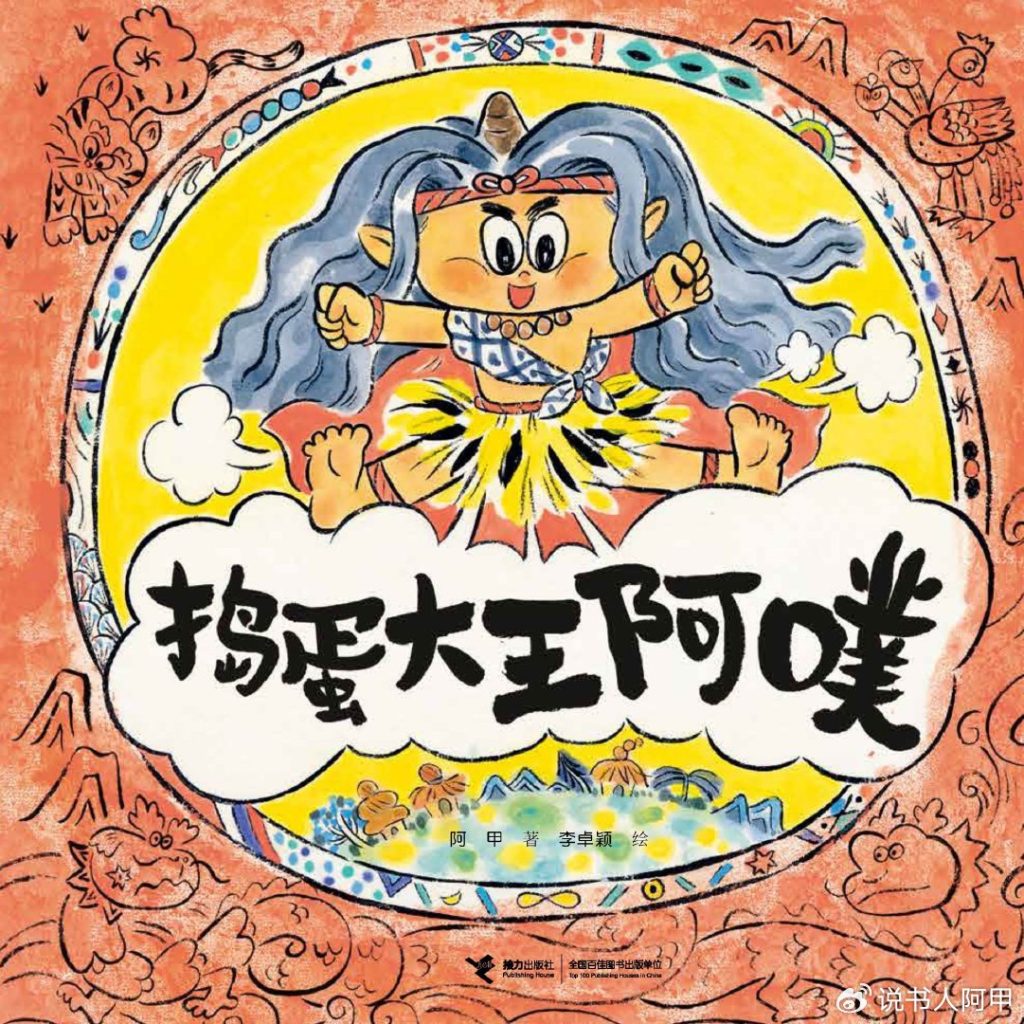

For example, didn’t I recently publish the story of “The Mischief King-A-Pooh”? I actually borrowed a lot of traditional stories, not only from China but also from abroad. What I want to do is to use these traditional stories to say something new that belongs to our era.

One of the core points I want to express is: there is nothing new under the sun. Even if you tell a story that “seems” has never been told before, you can eventually find its prototype — it’s just told in a different way.

Human emotions and complex interpersonal relationships have long been thoroughly explained by our ancestors. But today, we use an old shell to tell a new story. The key lies in what your new story is about.

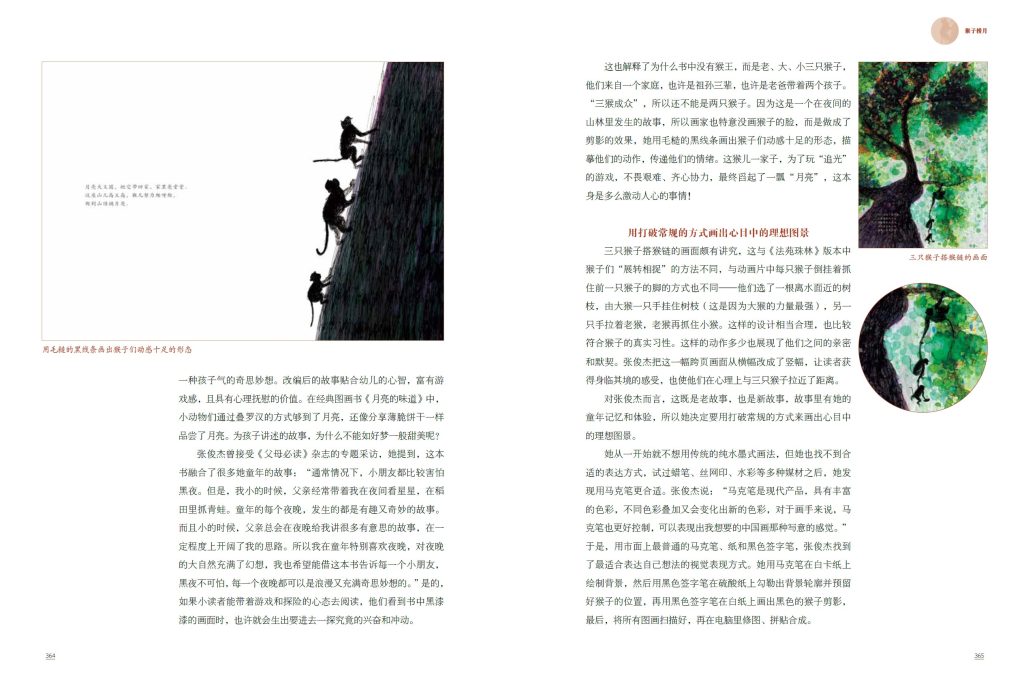

For example, the book “The Monkey Catching the Moon” introduced in my book won the first prize of the Xinyi Picture Book Award that year.

If you read it, you will find that although it looks like a traditional story, the story is actually completely different. It is said that the original version of “The Monkey Catching the Moon” may be a Buddhist story from India.

But the picture book version was rewritten by a “female macho” born in the 1990s. It looks like a traditional story, but it is actually a rewrite of her own childhood memories. This is a great creation! She put her childhood memories, her hopes for childhood, and her understanding of growth into it.

I think this is the kind of story we particularly need — using traditional stories to express meanings that today’s children can understand and feel.

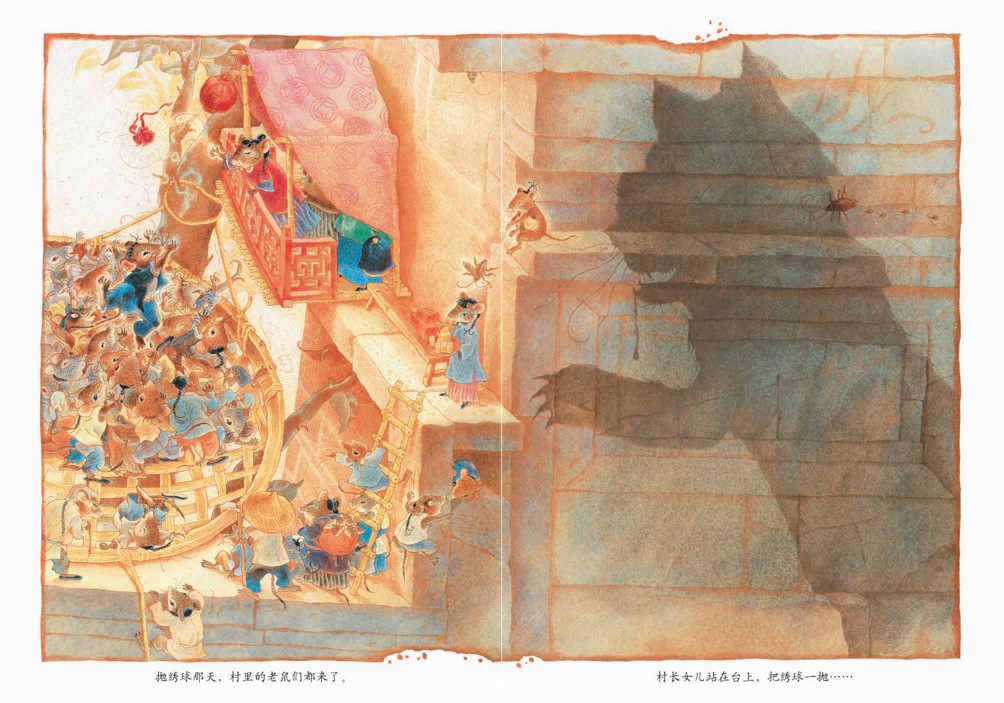

For example, I also recommend “The Mouse Marries a Bride” in my book. There are many versions of this story, but I particularly like the one originally published in Taiwan.

In my opinion, it is actually telling today’s children: Be brave and proactive in relationships between the sexes, don’t always wait for others to arrange things for you, and don’t think that happiness will fall from the sky.

Happiness is something you have to fight for.

Do you think there is such an expression in the traditional version of “The Mouse Marries the Bride”? Not at all.

This “contemporaneity” is added by the creator, but you will not feel it is out of place when reading it — it reads naturally and is particularly pleasing to the eye.

So I think retelling the classics is inevitable.

All the stories we tell are, in a sense, retellings of classics.

It’s just that many of us haven’t read so many stories, so we always feel that this story is new and that story is new to us.

But in my opinion, all stories are actually old stories.

(The above is the third part, to be continued)