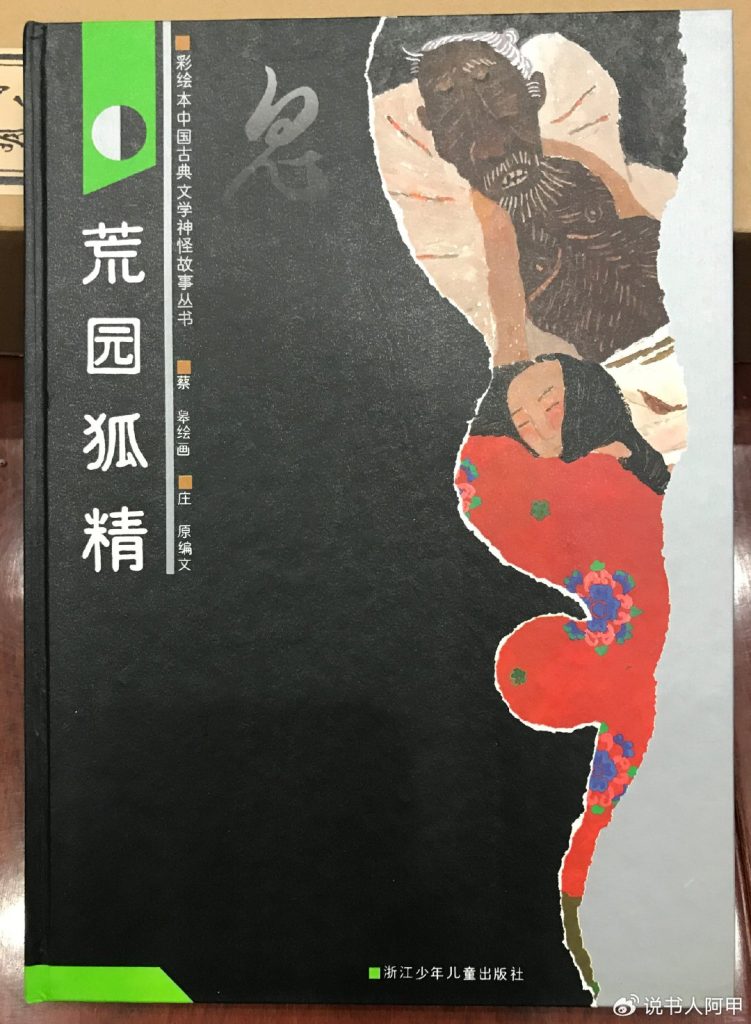

In 1993, when “The Fox Spirit in the Wild Garden” (the predecessor of “BoAi”) became the first Chinese picture book to win the Golden Apple Award of the Bratislava International Illustration Biennial (BIB), many Chinese people themselves could not believe it, and some even doubted: Could such a high-level children’s book illustration work be created by a Japanese?

Indeed, at that time, original picture books in China were still in their infancy. Even such an excellent work could only be printed in a thousand copies, and most of these were given away as gifts. The picture book market and readers were not yet ready. I had the good fortune to view one of those thousand copies, published in 1991, from a collector. I was impressed by its splendor and sophistication, which seemed unbecoming of the era, but I also noticed the influence of traditional comic strips on graphic narratives.

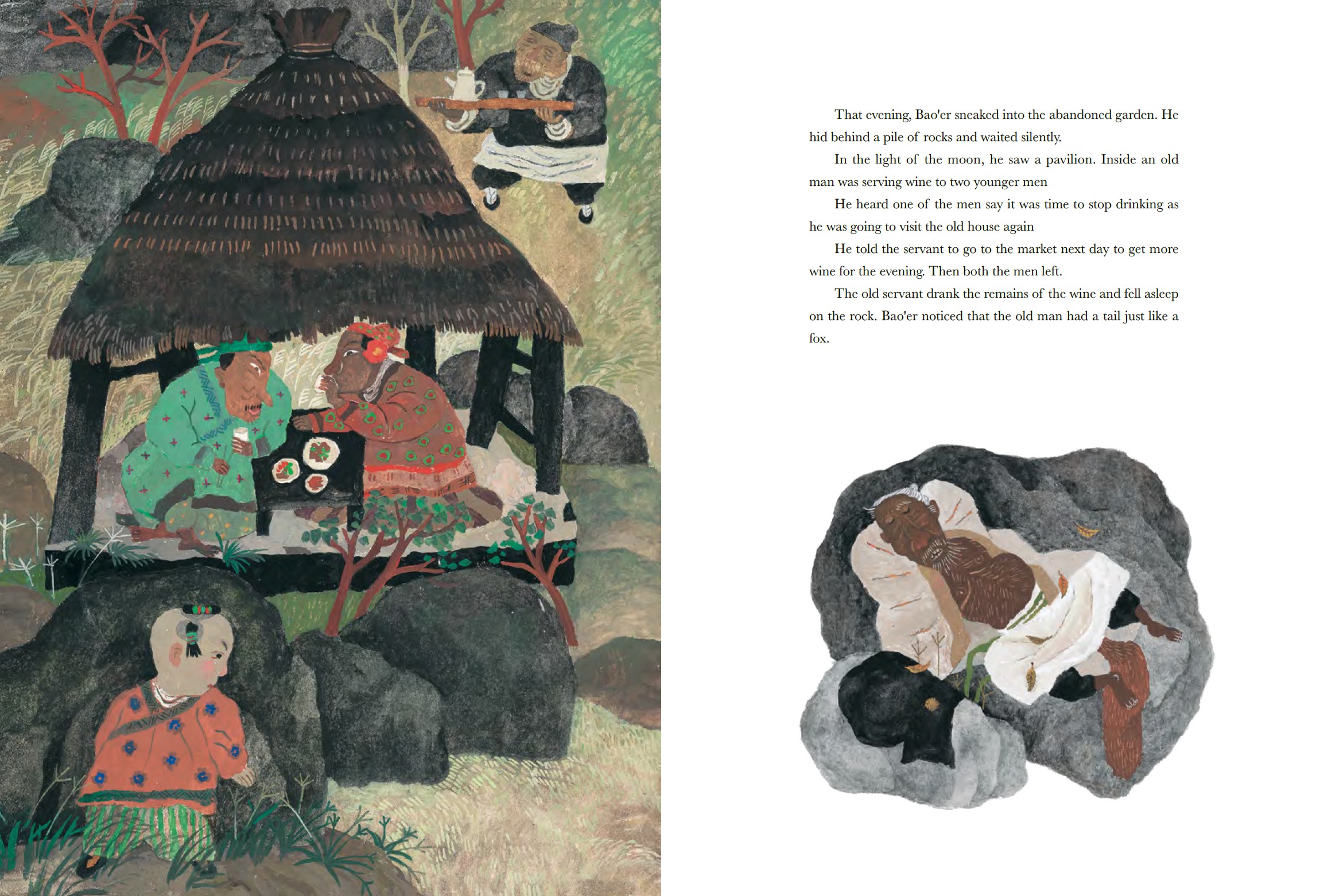

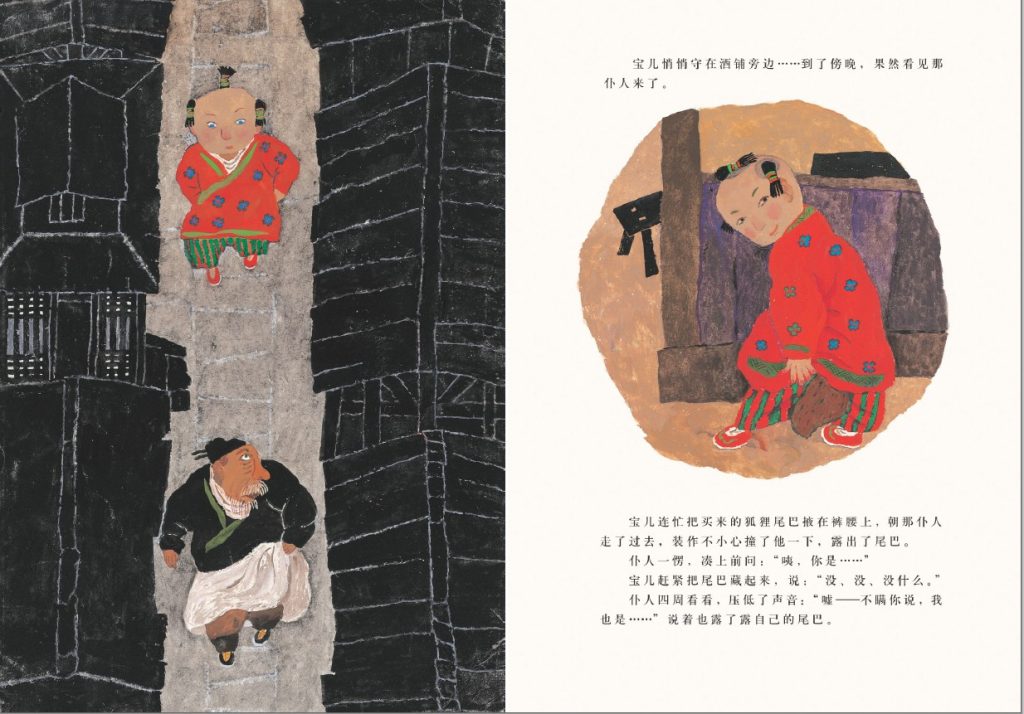

As we know, a comic strip consists of a picture with some text, usually in the middle of the scene, with a fixed-size frame, usually with the frame at the top and the text at the bottom. The original version of “The Fox Spirit in the Wild Garden” broke the boundaries of the frame. The left page of the double-leaf folio was a full-length, unframed painting, while the right page was a close-up with blank space around the edges. The relevant text was placed above the right page, but still divided into two parts, with arrows indicating whether the text belonged to the left page or the image below the current page. This can be seen as a transitional form of graphic narrative. However, Professor Cai Gao adapted this narrative method well, making the narrative rhythm perfectly match the needs of the story.

This story, adapted from “Jia Er” from the novel “Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio,” is filled with conflict and a volatile plot, which suggests a series of problems and solutions. For example, a child discovers his mother’s troubles and initially formulates a plan. Then, he slashes the fox’s tail with a knife, only to find the problem persists. After tracking the fox into the wilderness and discovering the truth, he must calmly consider a solution. This interlocking plot development creates a natural rhythm of tension and relaxation, perfectly suited to the aforementioned graphic narrative method.

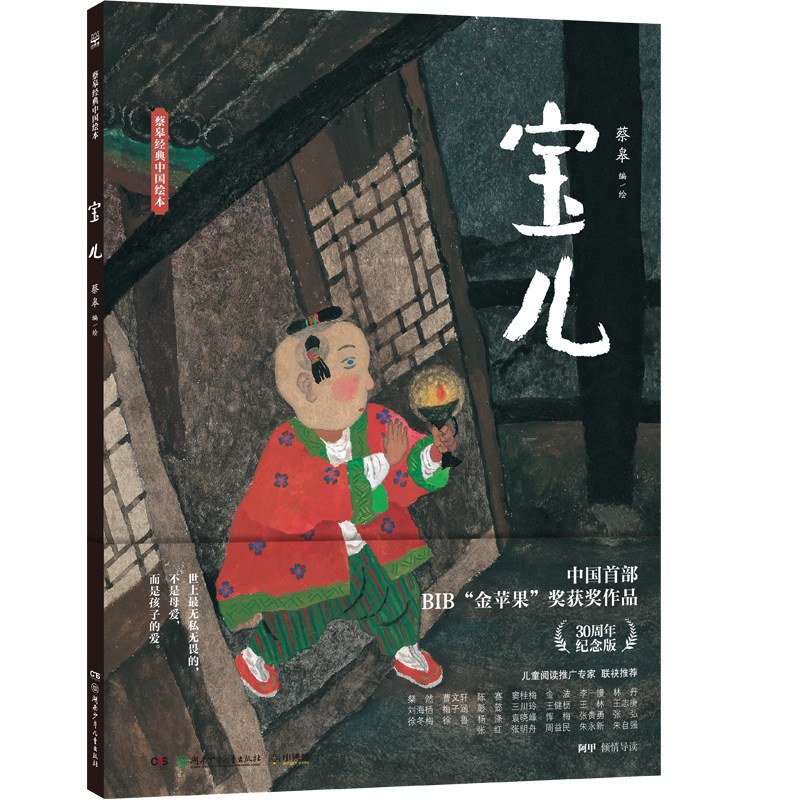

Admittedly, adapting Liaozhai stories for children is notoriously difficult. Even a tale like “Jia Er,” a story of witty demon-slaying and punishing evil and promoting good, possesses a certain somber undertone. The artist boldly uses black as the primary background, while using contrasting red and green to highlight the characters, especially the wise and courageous child. The story progresses from a downbeat tone to a positive one, building to a captivating climax. By the fairytale ending of “they lived happily ever after,” the previously darkened scenes are revisited, and the pure black offers a powerful sense of power. While this work may not be appealing to children, its inherent simplicity and honesty will surely inspire understanding and respect in thoughtful children.

The 2008 reprint of “Bo’er” was a highly successful adaptation. The title was changed from “The Fox Spirit in the Wasteland Garden” to “Bo’er,” further aligning the book with children’s stories. For the first time, the young hero was named “Bo’er” rather than “the merchant’s son,” and the focus shifted from the fox spirit’s mischief to the young hero’s exorcism. Careful readers will notice that the story downplays the details of the fox spirit’s entanglement. Instead, the narrator adds necessary explanations during the exorcism process, including Bao’er’s request for poison, poisoning the wine, and storing it in a liquor store, to prevent accidental harm. This demonstrates Bao’er’s attentiveness and sense of responsibility, while also setting a good example for potential children.

Yet, for some reason, the 2008 version ends with Bao’er exorcising the demon, “peace returns to Bao’er’s family, and the family lives happily together.” This is perhaps a typical fairy tale ending. But since this is the story of a young hero, I imagine readers of all ages will be eager to know, “What happened next?” “What happened to Bao’er when he grew up?” This is addressed in Pu Songling’s original story, and only then can the story be complete.

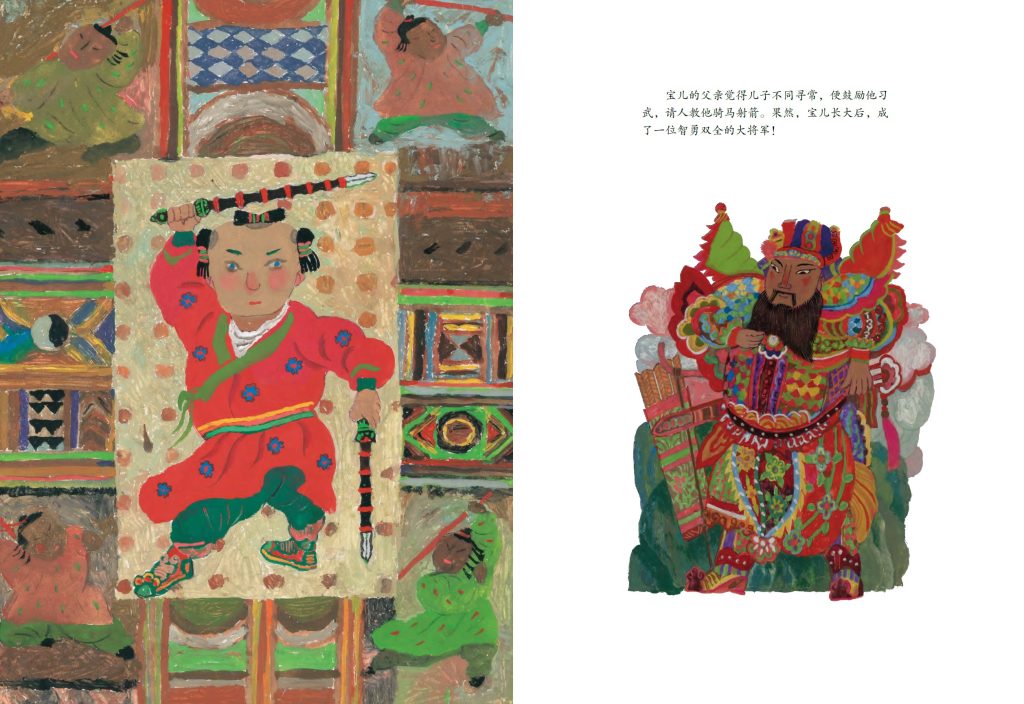

I’m delighted to have reinstated the ending design in the latest version of “Bao Er.” I really like the finale, which resembles a door god painting, drawn by Teacher Cai Gao. It adds a touch of festive joy to the story, completely transcending the atmosphere of a fox spirit tale. I believe children will linger a little longer in front of this image, which will completely relax their nervousness and inspire them to see the promising future of their little hero.

For adults who care about children’s education, the story of “BoAi” offers some inspiration. For example, we should never underestimate children and give them more trust and opportunities to develop. Furthermore, when it comes to education, we might learn from BoAi’s father and respect children’s preferences and strengths, teaching them in accordance with their aptitude.

I think if Pu Songling were still alive, he would be happy to see his stories adapted into such childlike and inspiring picture books.

Written in Beijing on January 24, 2021