Children’s kindness and wildness are, at their core, complementary forces—both are essential elements in awakening the vitality of life.

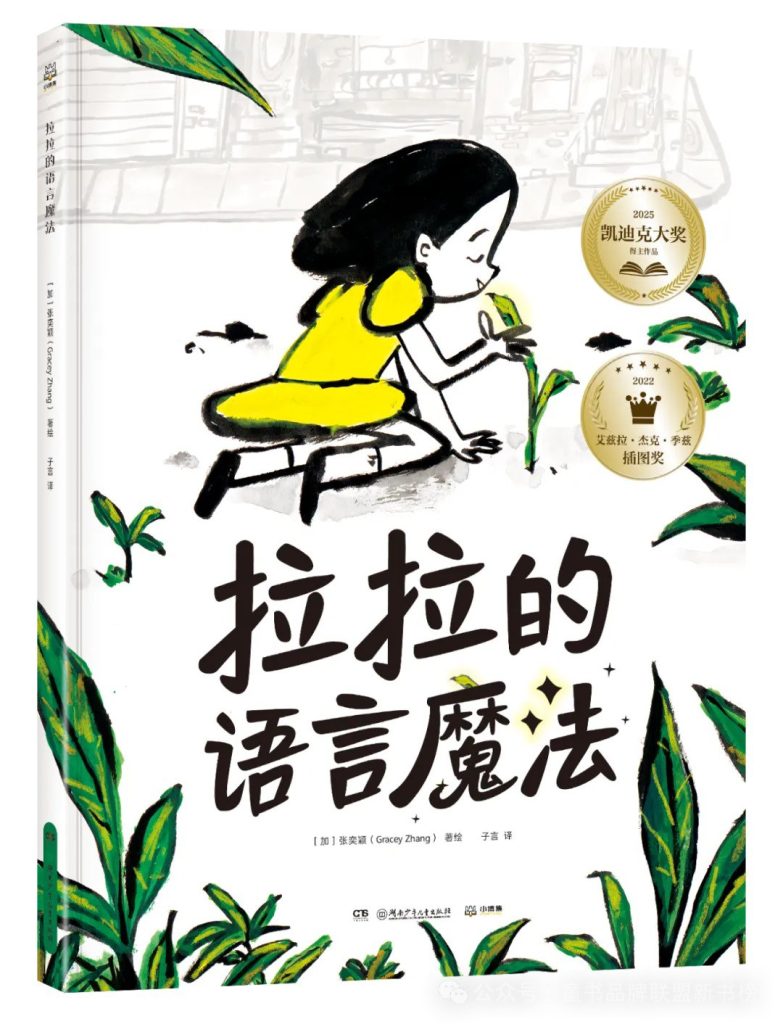

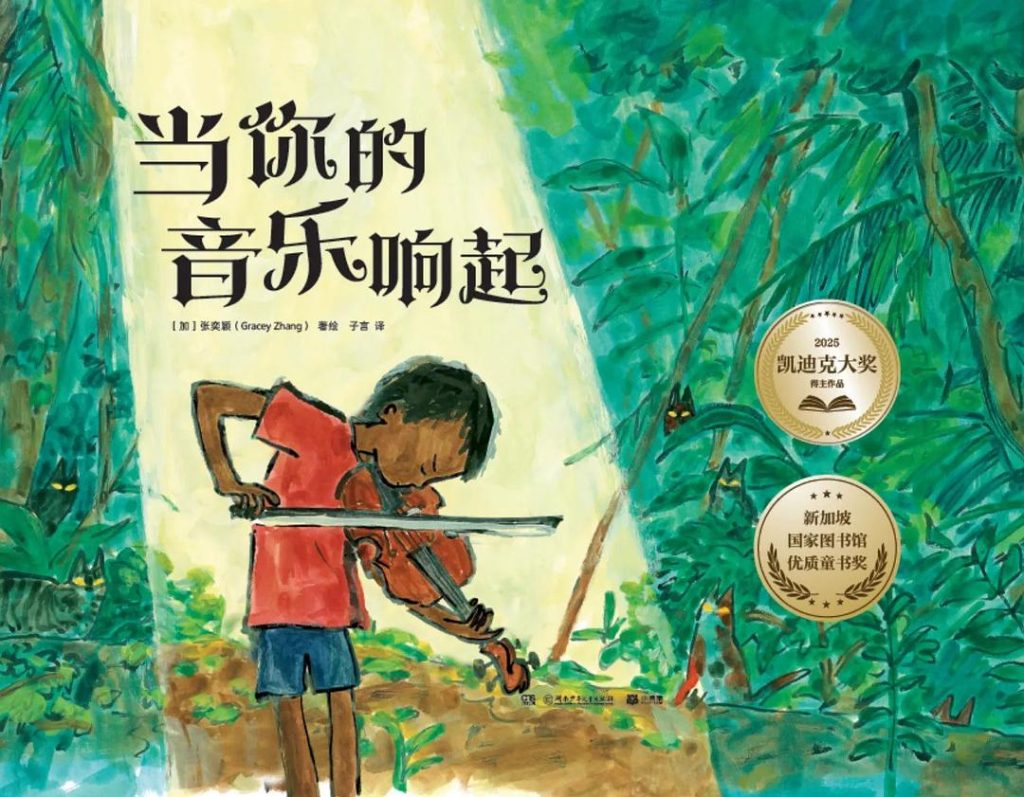

Gracey Zhang has quickly emerged in the field of children’s books with her unique visual style and delicate ability to capture emotions. Her debut picturebook “Lala’s Words”, published in 2021, was eye-catching and won the industry’s prestigious Ezra Jack Keates Illustration Award in 2022. In recent years, Gracey Zhang has collaborated with authors on at least six picture books, all of which have been widely praised. Among them, The Upside Down Hat (written by Steven Baltsar) and Nigel and the Moon (written by Antwan Eady) have already been published in Chinese editions. However, it is her author-illustrated works that remain the most compelling. Her second solo title, When Rubin Plays, will soon be introduced to Chinese readers alongside her debut, Lala’s Words.

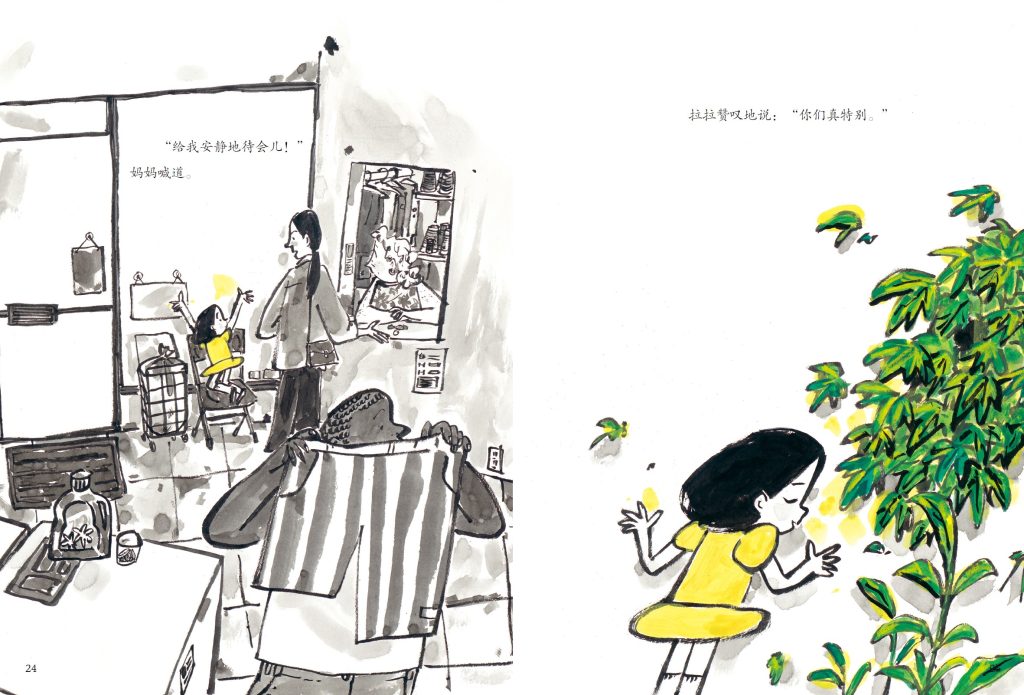

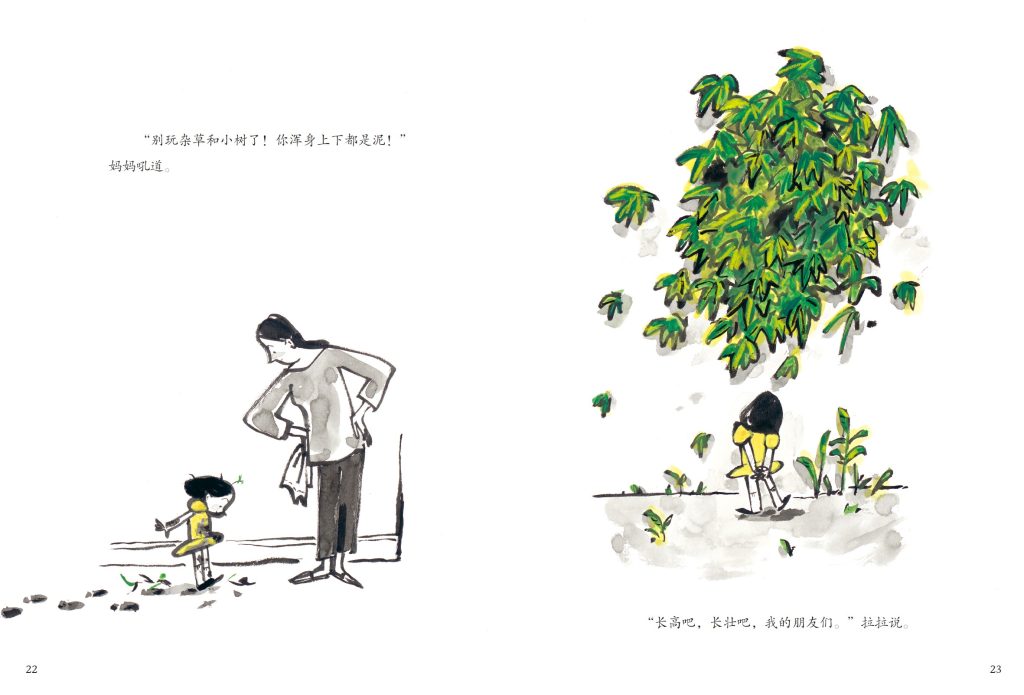

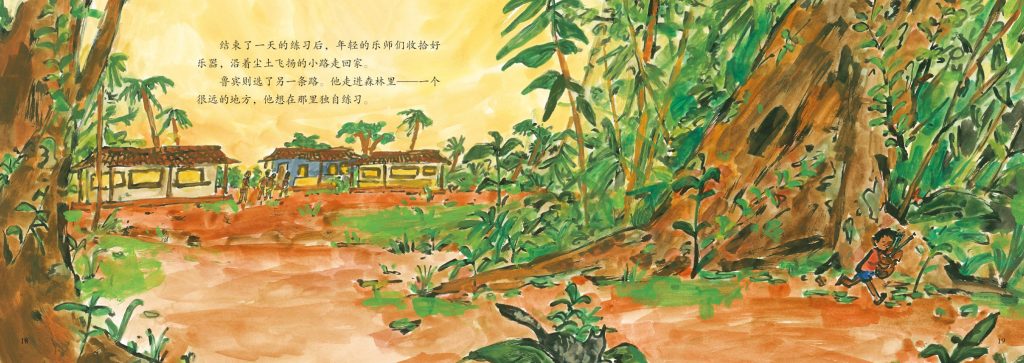

Lala, as described by Gracey Zhang, is a Chinese immigrant girl who is energetic and kind-hearted. In her mother’s eyes, she is a little “wild”. She is always unwilling to stay at home and would rather spend the whole day with wild flowers and weeds. What her mother cannot understand is that Lala actually expresses her love for the world through “dialogue” with plants. “Lala’s Words” not only shows Lala’s unique connection with nature, but also conveys the power of language and the healing power of kindness. “When Rubin Plays” focuses on the growth of a local Bolivian boy, Rubin. The background is set in a small town on the edge of a “wild” forest. Rubin conducts his own musical exploration with the help of animals, highlighting the joy of free and unrestrained self-expression. Both books explore the impact of cultural differences on individual growth and show the “magic” of the coexistence of kindness and wildness in children’s hearts.

Picture book enthusiasts may be more familiar with Ezra Jack Keats (1916–1983), who created classic works such as “The Snowy Day”, “Peter’s Chair”, “Whistle for Willie” and “Goggles”. Born into a Jewish immigrant family, Keats brought a unique sensitivity to children growing up in diverse cultural backgrounds. His most celebrated works focus on a young Black boy named Peter, and these stories—widely acclaimed and award-winning—significantly transformed the landscape of picture book publishing. The prestigious award named in his honor recognizes artists who make outstanding contributions to diversity and inclusion in children’s literature—an ethos that Gracey Zhang’s work embodies with remarkable clarity and warmth.

Unique illustration style

However, for most Western readers, the most attractive thing about “Lara’s Words” is the perfect match between its illustration style and the story itself. The New York Times book review praised its unique illustration style, “blending warmhearted mltiethnic urban caricature with a bold-lined rough-and-tumble zeal, is wholly original.” And Kirkus Reviews commented: “Lala’s enthusiasm blossoms on the page.” Paul Swydan, the owner of the The Silver Unicorn Bookstore, exclaimed: “This picture book is breathtaking, and Zhang’s use of color really helps the story come alive. It’s like a modern inverse of The Giving Tree .”

The reason why I associate with The Giving Tree is that, visually speaking, it is mainly the use of black and white line drawings. Both books are full of emotion and tension. But why is it a “inverse”? On the one hand, The Giving Tree is actually the process of a tree that keeps giving and turns into an old stump, and the life fades away. However, Lala uses her language magic to make her “amazing” plant friends realize the “amazing” life bloom. On the other hand, Lala’s Words still adds bright and warm colors, making people feel the vitality of life, as if there is really magic.

I had the opportunity to ask Gracey questions via email. Two of the questions were: Why does this book use only simple yellow and green colors, but still leave a deep impression? Why is Lala yellow? Gracey’s answers were:“I’ve always loved black and white art, and yellow just seemed to be the right colour for Lala. Sunshine, runny egg yolks, flower pollen, and hazy summer days.“Of course, I agree with the artist’s answer. But the yellow labia also reminds me of the little girl in yellow clothes in “Stone Soup”, the descendants of the dragon with yellow skin, and the noble yellow that could only be used by the royal family during the imperial period…

The Fan Brothers, also Chinese picture book artists, created “The Night Gardener”, “Ocean Meets Sky” and “The Barnabus Project” which are also very popular in China. They also praised:“Lala’s Words is really about magic; a special kind of magic called kindness. Like the sunlight and falling rain, kindness nourishes the world around us. This book, with its lovely art and whimsical story, will also nourish the reader.”

About the magic of mother-daughter communication mode

Although this can be said to be an exciting “magical” story, the way the mother in the book spoke to Lala also made me read something that might be easier for Chinese people to read. I couldn’t help but ask the author in an email: “Does this story have some kind of personal experience? Although I am very happy to see that Lala finally changed her mother, Lala’s mother always reminds me of the more negative comments that many Chinese mothers often use on their children…”

Zhang’s response was straightforward and warm:“Also you’re completely accurate with your parallels. I wrote Lala’s Words during a period of tension with my mother when our relationship was more rocky than usual. I was reflecting on how we related/talked/communicated with each other and how far back this miscommunication went to childhood and more. I suppose writing and illustrating the story was a way to show her how I was feeling without having to go through another difficult conversation. Like I was saying “here read this, this is how I feel.””——It was a perfect idea to communicate effectively with my mother by writing a book. At the end of the book, mother and daughter not only reconciled, but also expressed deep love for each other.

I later found Zhang’s acceptance speech when she accepted the award online in 2022. She specifically mentioned:“ Lala’s Words is a story that I wrote from my own experience growing up with my mother, a story that spoke to a lot of fears and miscommunication between a lot of immigrant mothers and children. All the things that go unsaid or are said. I realized it wasn’t just me and my mother, but it was a pattern of generational communication and relationships between her mother and all the mothers before that. ”——I would like to say that this is also the deeper level of language magic that touched me about this book.

Diverse visual expressions

“Lara’s Words” is somewhat autobiographical, while “When Rubin Plays” is more free and unrestrained. In her debut picture book, Gracey Zhang adopts a minimalist illustration style—predominantly black-and-white linework accented with touches of color. This restrained visual language not only highlights the emotional core of the story but also deepens Lala’s connection with the world around her through its elegant simplicity. In contrast, her second author-illustrated work bursts with rich, vivid colors. Set in the emotionally vibrant landscape of Latin America, the story teems with the wild vitality of nature and the pulse of music. The illustrations are saturated with bold reds, oranges, greens, and blues. At the story’s climax—where Rubin’s music reaches a fever pitch and animals whirl through the scene—the imagery explodes into a dazzling spectacle of sound and motion, leaving readers almost breathless with its exuberance.

Through her masterful use of color, Gracey Zhang demonstrates a remarkable ability to adapt visual elements to suit the emotional tone and cultural context of each story. Her seamless integration of visual art and narrative text infuses her works with a distinct emotional resonance. Beyond enhancing the visual appeal, her thoughtful interplay of color and line deepens the thematic layers of her storytelling, allowing the illustrations to echo and expand upon the emotional heart of the tale.

Though different in plot and setting, both of Gracey Zhang’s books reveal a kind of “magic” that lives within every child. In Lala’s Words, Lala’s gentle words and quiet care breathe life into the plants she loves—a magic rooted in kindness, showing how language can shape and transform the world. In When Rubin Plays, Rubin discovers his magic through music—a magic born of his yearning for self-expression and his deep love for sound and rhythm. Each child, in their own way, taps into a powerful inner force that brings vitality and wonder to the world around them.

The magic that can change the world

Though these two forms of magic may appear different on the surface, they both arise from the same source: the purity and strength at the heart of a child. In essence, a child’s kindness and wildness are not opposites but complementary forces—each essential to awakening the vitality of life. In Gracey Zhang’s hands, kindness and wildness are never in conflict; instead, they coexist as the most precious elements of a child’s spirit. It is through this unique blend of gentleness and untamed energy that children unleash their truest vitality and creativity.

It is truly heartening to see a new star rising on the global picture book stage—Gracey Zhang, a gifted Chinese Canadian illustrator and storyteller. Her unique cultural background gives her a distinct perspective on the world, allowing her to reflect on her own upbringing while embracing a broader, more inclusive view of humanity. Through her work, she reveals the “magic” within the world of children—a magic that doesn’t just dwell in kindness or wildness alone, but thrives in their harmonious coexistence. Her stories celebrate this duality, capturing the vibrant, complex spirit of childhood with remarkable grace and vision.

I believe this dual kind of “magic” holds the power to awaken the deepest vitality of life—not only transforming the worlds within stories, but also leaving a lasting impact on readers, both young and old.

Ajia written in Beijing on September 13, 2024