French children’s book author and illustrator Claude Ponti (born 1948) was twice shortlisted for the Lindgren Memorial Award and holds a high reputation on the global picture book stage. A prolific writer, Ponti has over 30 works translated and introduced into China, with works related to “Blaze the Chicken” being the most popular. Ponti’s style is instantly recognizable, blending vibrant colors and fantastical creations. His images are intricately detailed, revealing a nearly limitless narrative potential, humorous, and rich with metaphor and symbolism. This makes his works particularly well-suited for repeated reading, or perhaps even “not understanding” after just one or two readings. His multi-layered narratives are particularly appealing to readers of different ages, allowing them to unravel multiple meanings.

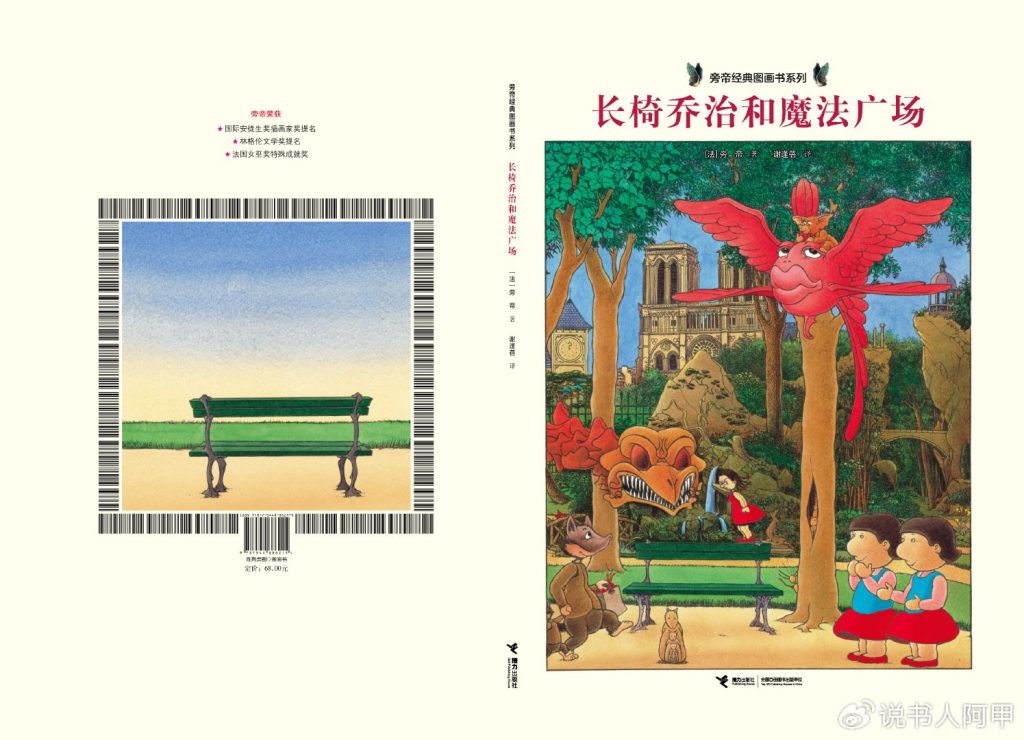

Here, I would like to use Georges the Bench (Georges Lebanc) , originally published in 2001, to demonstrate the unique charm of its multi-layered narrative.

Let’s quickly read it first

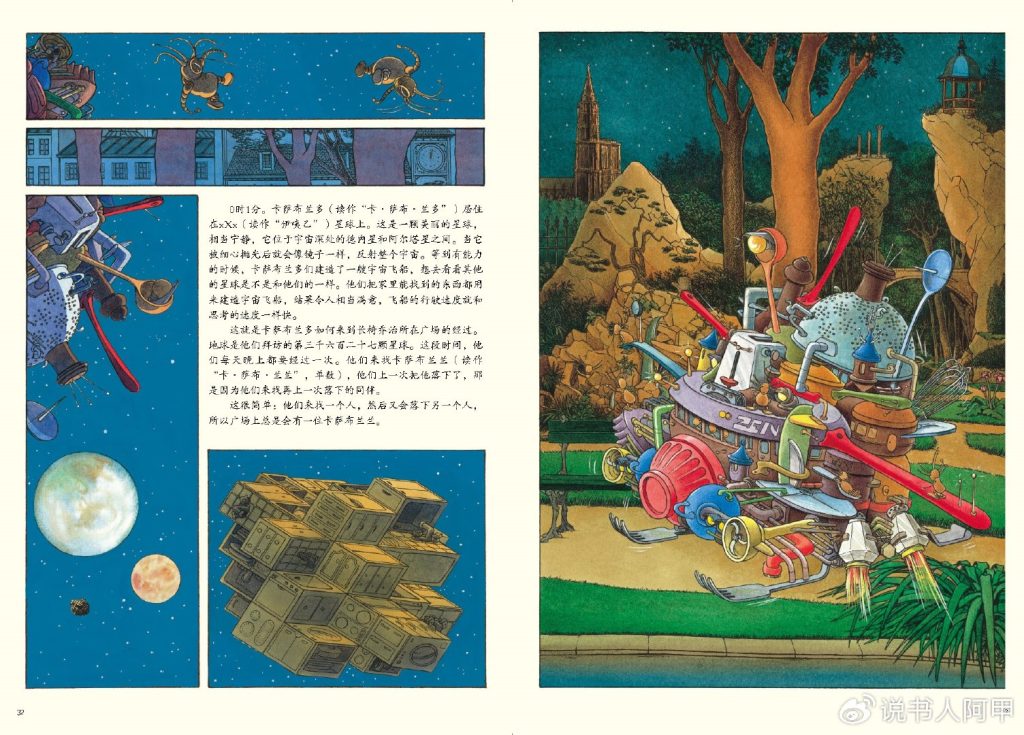

The text begins: “George is a bench. For many years, he has lived in the Square Albert-Duronquarré.” Indeed, the protagonist of this story is not a person, but a chair—a chair with a name, memories, and experiences. The story begins in the square, but it goes far beyond that.

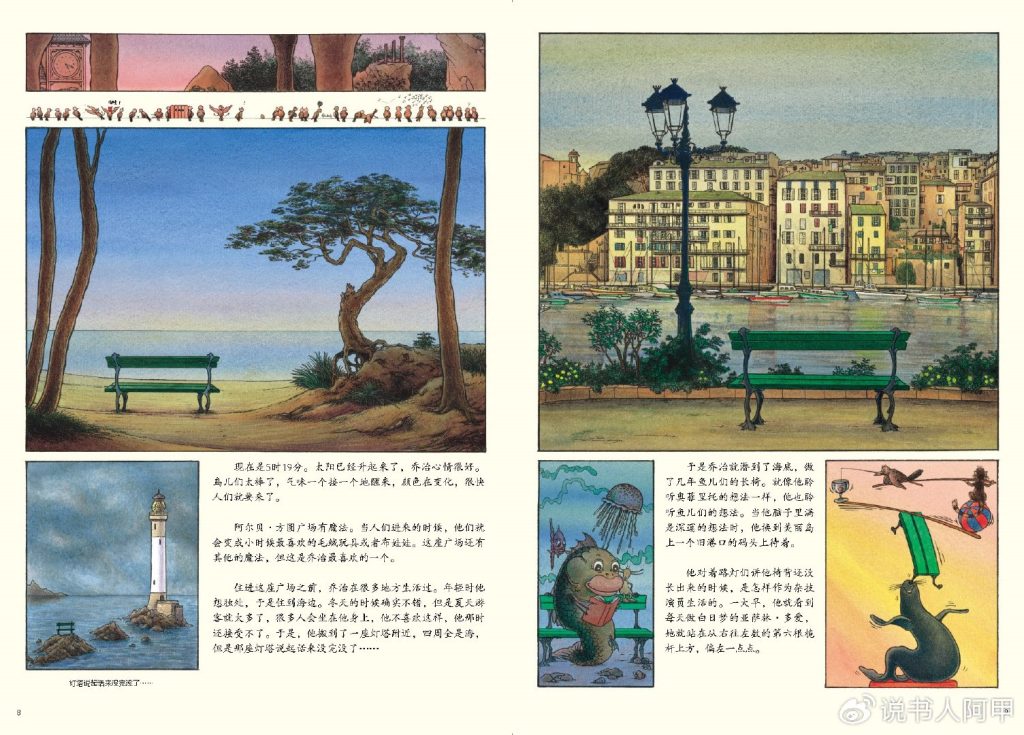

Pontti uses images to depict the square garden where George lives. Passing by it for the first time, readers might perceive it as just like any other city square: greenery, lawns, rockery, and seating—a part of the city’s public space, where people socialize, relax, and unwind. George, on the other hand, is a typical park bench—with cast iron legs and a frame, and a long wooden seat and back. If it weren’t specifically mentioned, readers might not particularly notice the bench’s existence.

Particularly interesting, Pontius goes on to explain that George, as a child, was a small stool that gradually grew into a bench. Before the back of his chair had grown, George was a performer in an acrobatic troupe, experiencing both danger and laughter. Today, George has grown into the figure you see in the painting. In other words, all members of George’s family are chairs: they are the king’s throne, the giant’s stool, the ejection seat in an airplane, even the toilet seat… Each chair has its own destiny. George, on the other hand, has lived a diverse life: by the sea, under the sea, and in the old port. Today, he has chosen to make his home at Square Albert-Duronquarré.

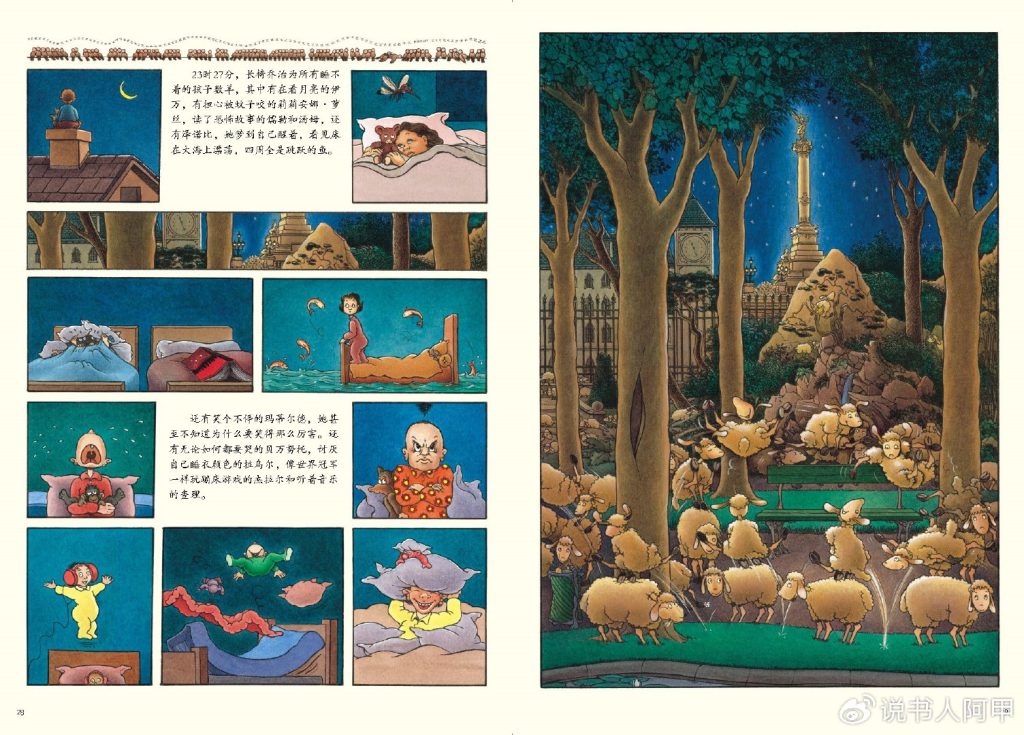

Why this square? Because there is magic here.“When people come in, they become their favorite stuffed animal or doll from childhood. There are other magical things about the square, but this is George’s favorite.” The text consists of just a few simple sentences, but the pictures are filled with dazzling details waiting for readers to explore.

First, the strange creatures of all shapes and sizes, with exaggerated forms and peculiar expressions, yet with authentic and vivid personalities, imbue this bizarre world with vitality. Secondly, the book’s unbridled imagination transports the reader into a world beyond reality. Furthermore, the rich details in the images allow readers to discover many hidden stories and characters. Whether it’s the small creatures in the background, the subtle changes in expression, or the unique buildings and objects, all demonstrate the author’s meticulous pursuit of detail. However, these details require repeated readings to gradually discover…

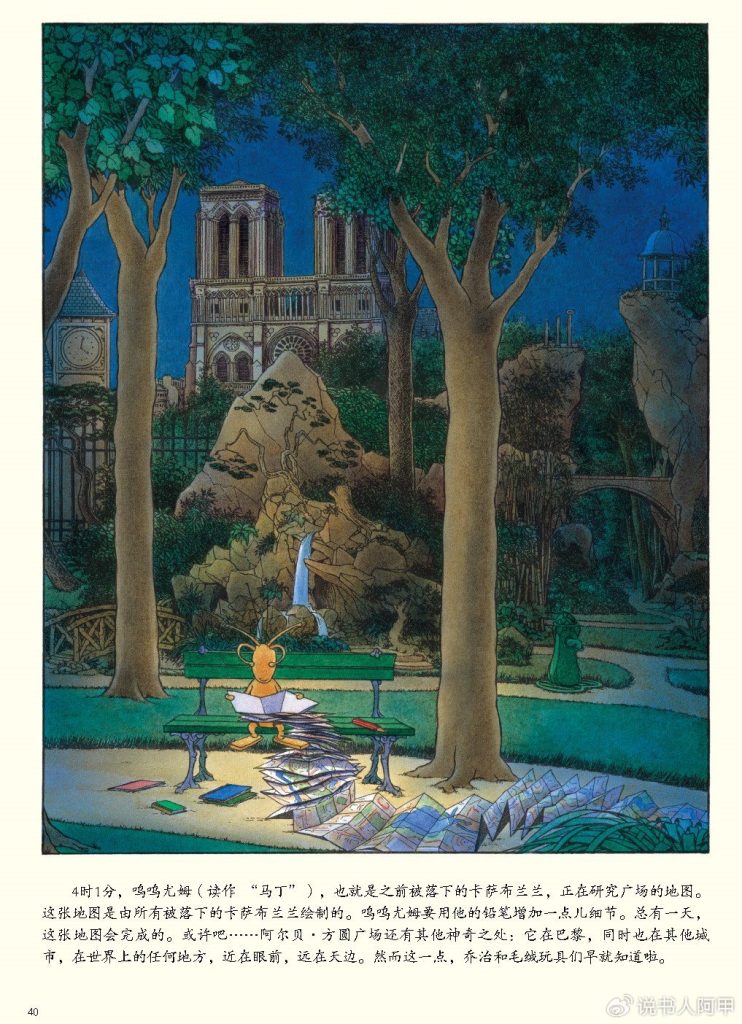

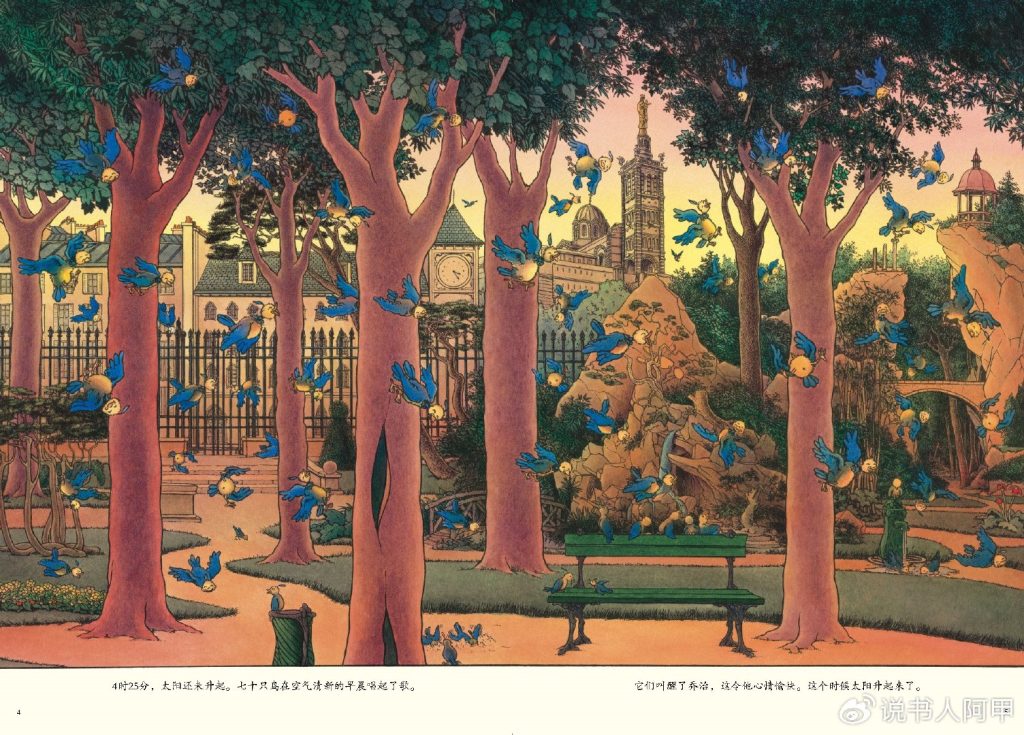

Let’s quickly flip to the end of the story: from 4:25 a.m. one morning to 4:01 a.m. the next, after nearly 24 hours of bizarre and whimsical revelry, everything returns to calm. The ending is neat and tidy: “There’s something else about the Place Albert Square: it’s in Paris, but it’s also in other cities, everywhere in the world, near and far.”

What might children read?

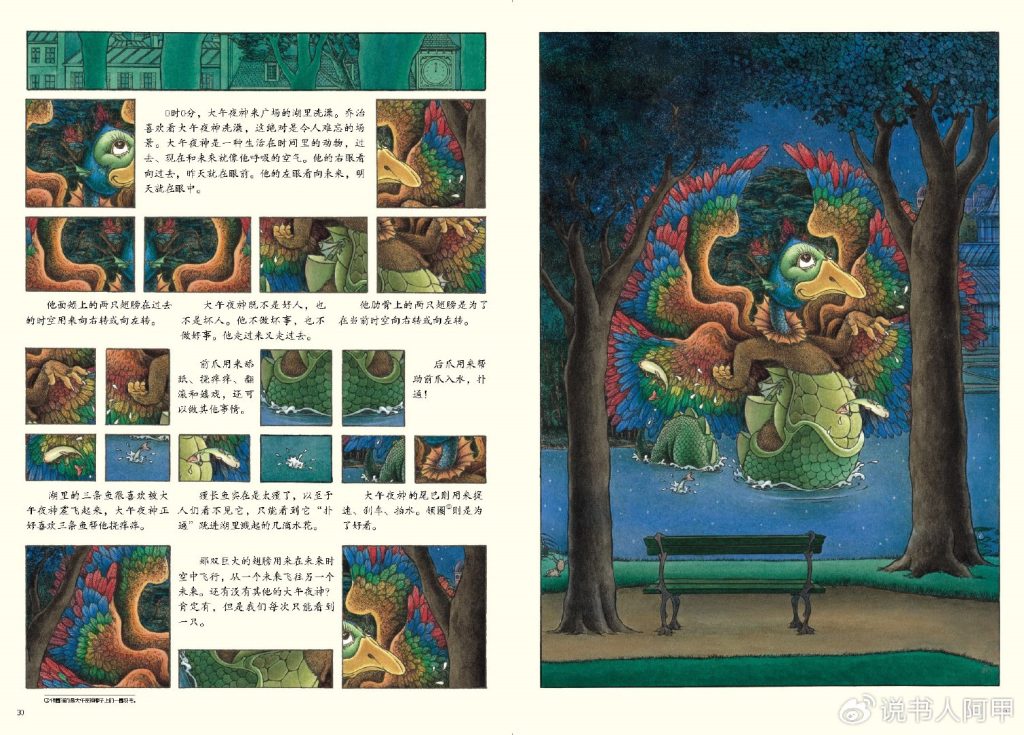

If you ask me: What is the moral of the story of George the Bench? How can children benefit from it?—I honestly don’t have an answer. This book doesn’t seem to be trying to teach a moral; it’s more like a grand game of words and pictures, presenting many fantastic fantasies while vaguely conveying a deeper meaning. For example, “At 0:00, the Great Midnight God came to bathe in the lake in the square.” Judging by the timeline, this must be the moment when the most important character appears, but “The Great Midnight God is neither good nor bad. He does neither evil nor good.” This wonderful creature is merely a manifestation of time, spanning past, present, and future, inherently neither good nor evil. If children could understand this, wouldn’t it benefit them for the rest of their lives?

From a child’s perspective, I believe this book’s rich visuals and whimsical plot will undoubtedly spark their intense curiosity. It’s truly a feast for the senses and imagination. The fantastical characters in this book immerse children in incredible imaginations. From pink birds to anthropomorphic dolls, from Barbize Persian dragons to the alien Casablanca, each character possesses a unique form and function. The beauty lies in the way these unique characters connect emotionally with young readers. Emotionally, Anaïs P. and her doll Melanie can inspire courage in a little girl feeling wronged; the grand dance of life’s giants can bring profound comfort to a baby feeling “life isn’t easy”; the pool of tears scene allows children to see that sadness can be accepted and released; and every child will resonate with the scene where George on the bench counts sheep for all the sleepless children.

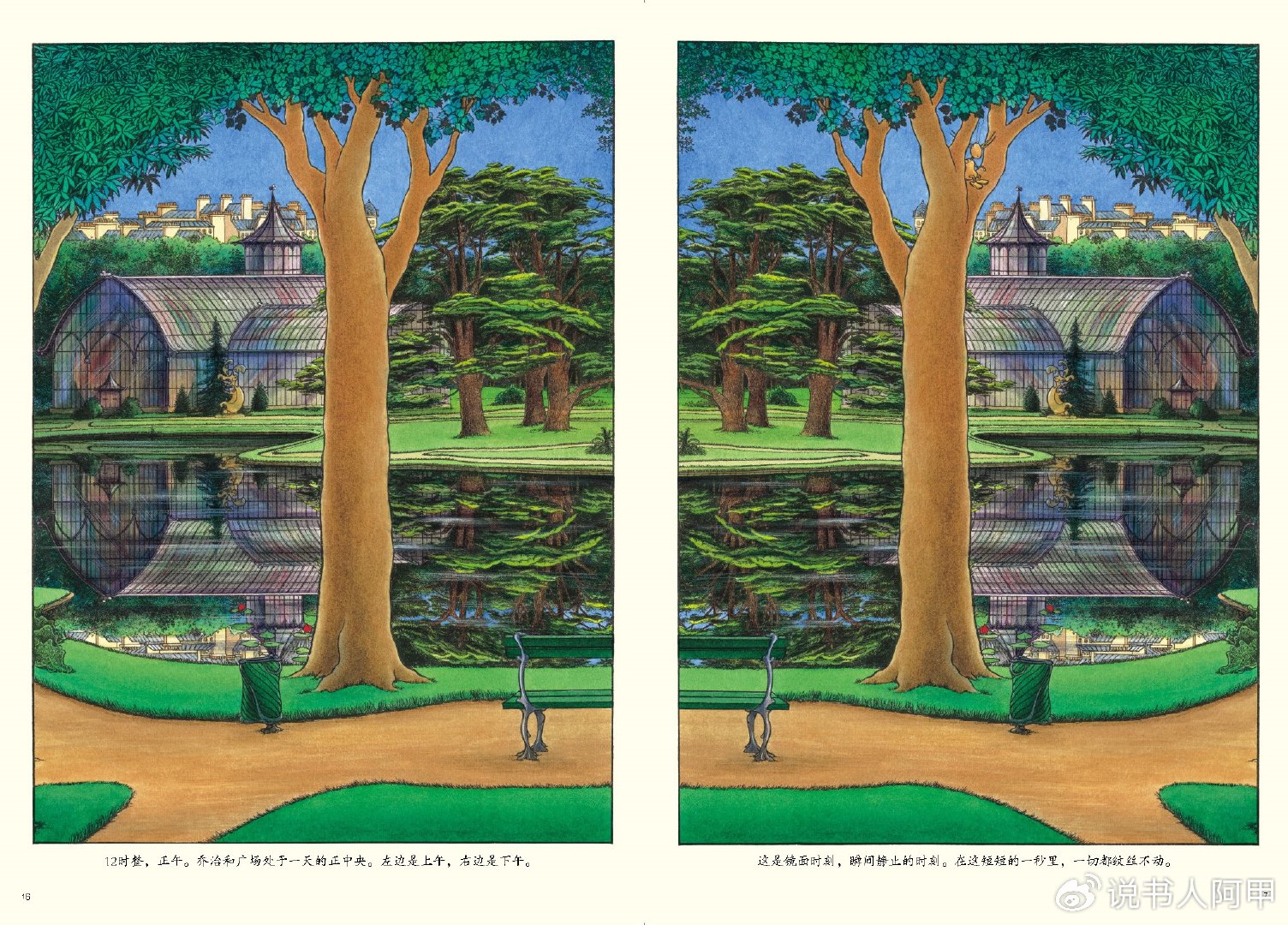

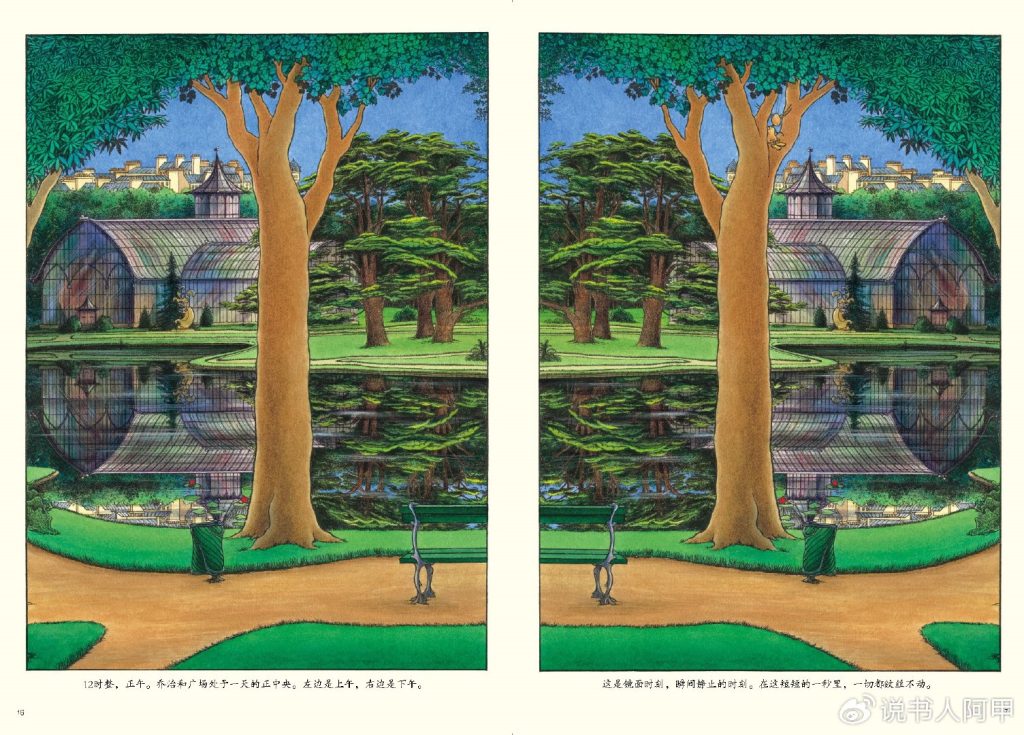

For young readers, the playful, illustrated stories easily engage them. The Magic Square’s ubiquitous nature teems with possibilities for adventure, allowing children to imagine themselves in such a place and participating in its magical activities. Each page contains numerous intriguing details to discover, subtly cultivating children’s observation and patience. For example, the folio “16:00, Tea Time” (“Afternoon Tea Time”) provides a detailed index to the image on the left page, allowing children to play a game by searching for specific elements within the image. This visual play (training) recurs throughout the book. The same scene may be repeated from different angles, such as before and after “12:00…Mirror Moment.” The square garden rotates, and iconic buildings (such as the glass greenhouse) and the changing background all offer interesting objects for observation.

The story unfolds over a 24-hour period, using time as a thread to present different characters and events at different points in time. There are wondrous happenings in the magic square, and scenes from another time and space, narrated through flashbacks. While reading, children can connect with the rhythms of daily life while also experiencing the broader flow of time. This may help cultivate a certain level of time management, but more importantly, it enriches their life experience by conveying diverse messages from different stages of life. This experience taps into children’s inherent imagination, and eclectic artists like Pontti aim to transcend conventional wisdom, using “imaginative thinking” to help them break free from stereotypes and cultivate creative thinking.

So I think the biggest benefit for children from reading such books is that they can realize through the aesthetically pleasing experience:Behind every ordinary scene, there may be hidden stories and magic.The only question is whether we have the vision to discover and the imagination to be creative enough.

What might adults read?

Take me for example. After reading “George the Bench and the Magic Square” for the first time, I was actually inspired to travel because I realized the magic square in the book was flying all over the world! If you pay attention to the pictures, you’ll notice that the iconic buildings in the background are constantly changing. Some of these beautiful buildings seem familiar, while others seem completely new. I was curious to know where they were.

In this AI-powered internet age, with the help of some search tools and travel guides with photos, you can easily find some of the main landmarks in the background as follows:

P3 Notre Dame Cathedral

P5 Notre Dame de la Patroness Church in Marseille

P11 Mont Saint-Michel Abbey in Normandy

P17 may be the tropical greenhouse of the Paris Botanical Garden

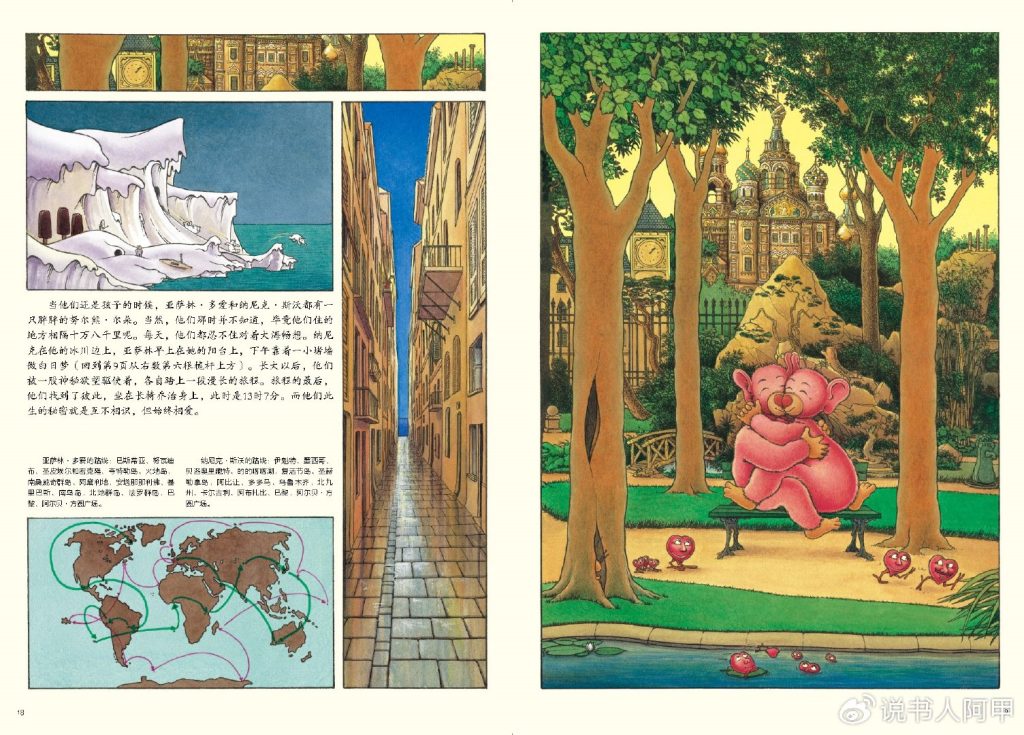

P19 Church of the Resurrection in St. Petersburg, Russia

P23 The Conciergerie in Paris

P29 July Column at Place de la Bastille in Paris

P33 Cathedral in Strasbourg

P35 Notre-Dame de Fourvière Cathedral in Lyon

There are also some scenes, perhaps in the Luxembourg Gardens, Montmartre Hill, Versailles Gardens, or a port in Marseille. In short, this magic square mainly travels around France, and occasionally goes to Russia. This echoes the hint at the end of Pontius Pierre: “It is in Paris, but also in other cities, anywhere in the world.”

Even more intriguing, however, is the connection between the iconic buildings in the background and the story unfolding on that page. What associations emerge? For example, at 1:07 PM, the chubby Noor Bear, owned by Yasarin Doai and Nanik Swo, meet on a bench with the Resurrection Cathedral in St. Petersburg as the backdrop. Is this a symbol of love and miracles? Or a lifelong bond? Or a rebirth into whole selves—they finally find themselves? Or, for example, the afternoon tea scene is set against the backdrop of the Conciergerie. Is this a playful reference to the eight wolves stealing drinks and snacks, hinting that stealing could lead to imprisonment? Even more amusing, all the sleepless children and the restless sheep appear beneath the July Column in the Bastille, a symbol of turmoil, change, and the spirit of freedom. Is this a call to action for the children to unleash their free spirits?

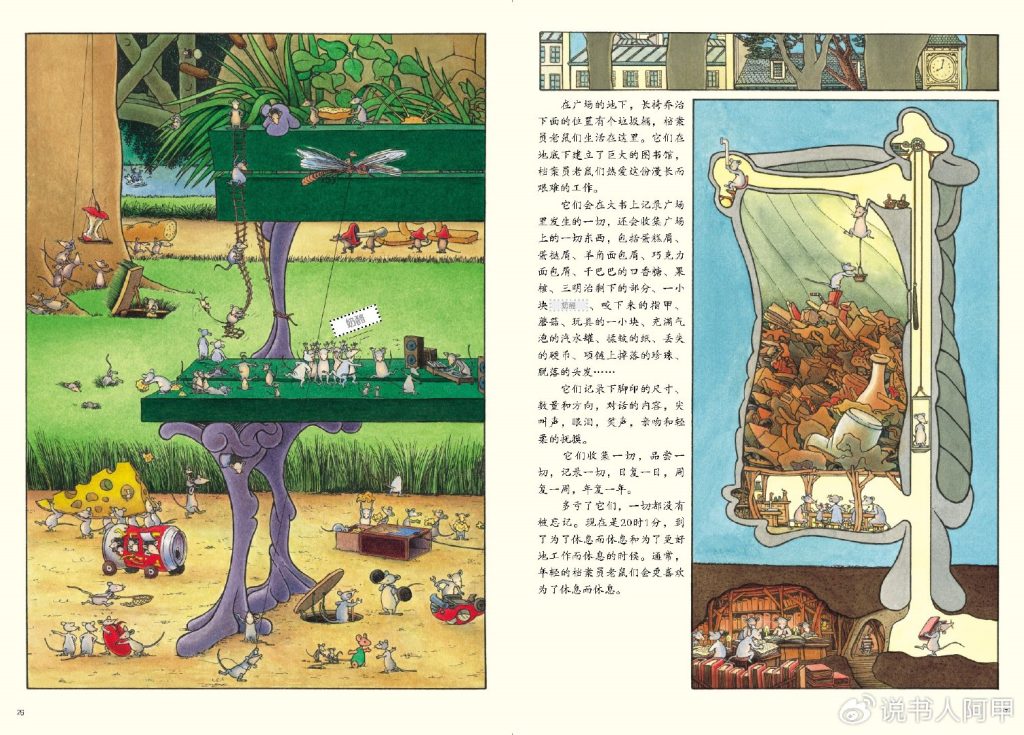

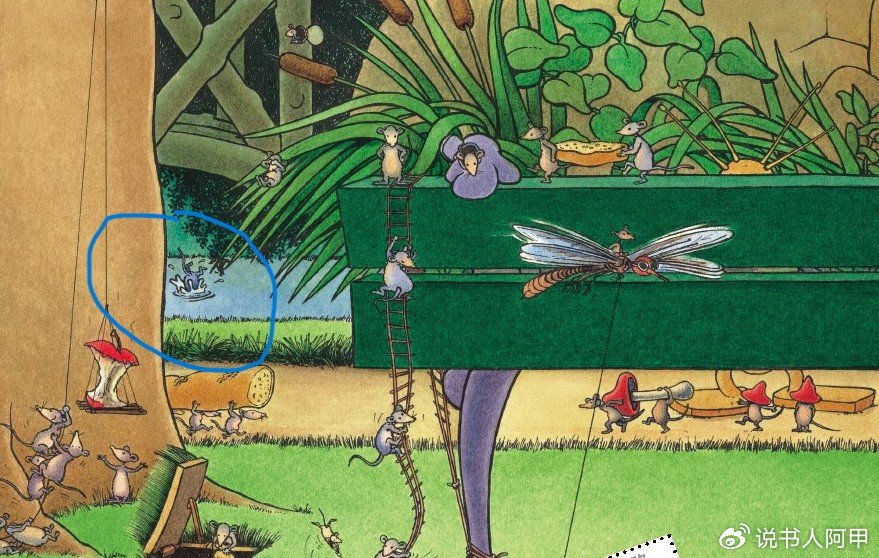

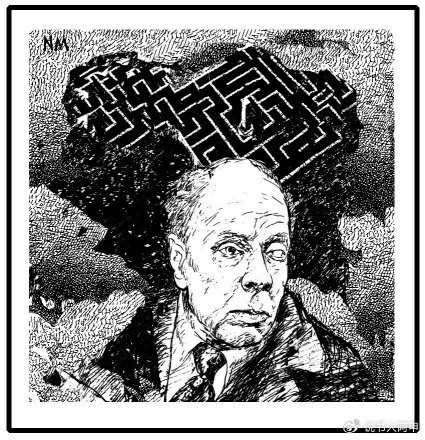

In short, the magic squares flying around the world may just be a fun and amusing visual game for young readers, but for older readers, they provide more room for historical and cultural interpretation, which depends on the readers’ life experience and reading experience. For example, as a super bookworm, I was deeply moved by the huge library built by the archivist mice on pages 26–27. These mice collected everything that happened in the square, including both extremely trivial material carriers and spiritual carriers of emotions and feelings. This made me think of Borges’ short story “The Library of Babel” and his often-quoted famous saying: “I have always imagined thatParadise will be a kind of library”.

The bizarre and humorous underground library in Pontius Pierre’s novel can be said to be a fairy-tale version of the Library of Babel, also symbolizing infinite knowledge and possibilities. Pontius Pierre himself loved this idea so much that he published a sequel 15 years later (2016).Le Mystère des NigmesThe story is about a magical square that has stopped moving due to the destruction of a monster. Worst of all, the documents, words, and letters maintained by the archivist mice have been mysteriously erased. To restore the lost culture, the mice must embark on a detective mission to find the missing files and clues, while also uncovering who carried out this destruction and what their motives were. In an interview after the sequel was published, Pontius Pierre said:“Culture is more than just the Mona Lisa.It’s in the experience we have when we look at it, the richness of the object, and the value we share with others through it.”

The maze of multidimensional space-time

When I read it for the fourth time, the word “labyrinth” suddenly popped up in my mind. This naturally reminded me of the labyrinth built to trap the half-man, half-bull Minotaur in ancient Greek mythology, as well as Daedalus, who was responsible for building the labyrinth, and his son Icarus, who flew too close to the sun and fell… Pontius might have thought of it too. If you pay attention,In the upper left corner of the picture on pages P26-27 , there seems to be an archivist mouse falling into a small pond!

Of course, you don’t have to make such an association. Technically, however, this picture book does have a maze-like structure. As mentioned earlier, this is a square that constantly shifts spatially. Take a closer look at the front and back covers: the protagonist, “George the Bench,” has just completed a complete rotation; the perspectives of the front and back endpapers also rotate roughly 180 degrees. If you try to imagine this square garden scene, the entire book resembles a holographic structure, with the mirror moment in the middle shifting spatial symmetry. Looking at the corresponding timeline, it’s roughly 24 hours. While the text indicates a time interval from 4:25 AM to 4:01 AM, the actual dividing time is around 4:00 PM, roughly the time between the “Dance of the Giants of Life” and afternoon tea. Comparing the first image (P3) and the last image (P40) in the text, you’ll notice that Pontius adheres very strictly to this structure. The clock in the first image indicates that the story begins between 4:07 and 4:08 AM.

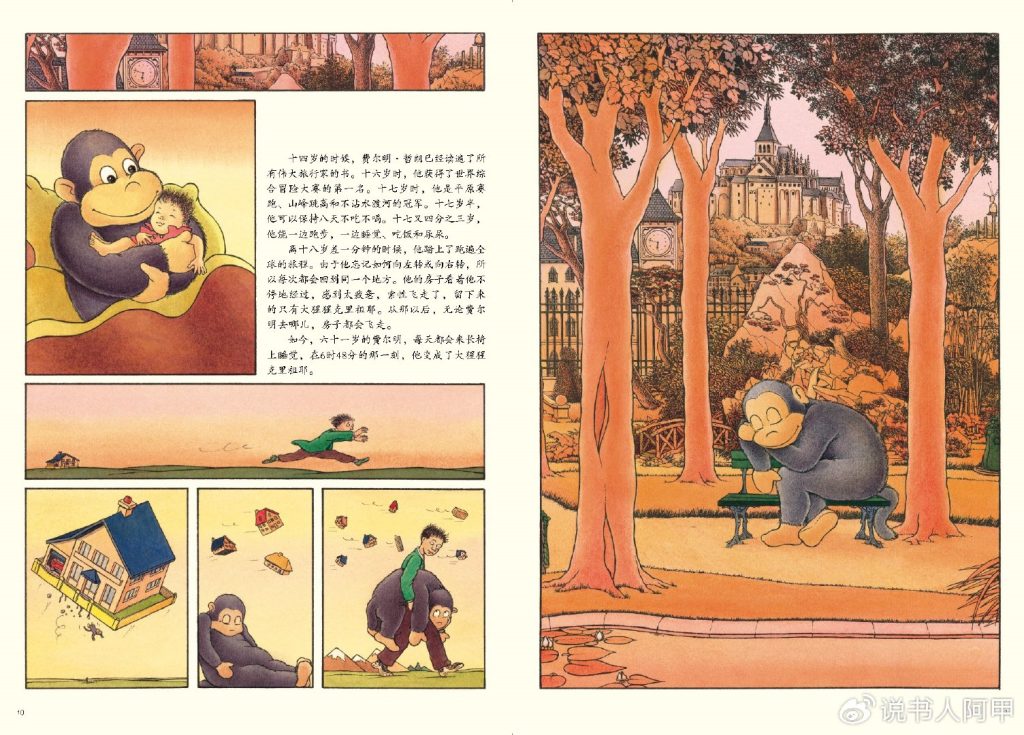

What’s truly bizarre is that, despite the clock’s timeline, the time in the square belongs to different beings: the time when the seventy birds sing, the time when the note-sucking Kemenino rats live, the time when Fermin’s gorilla, Krizuye, comes to sleep on the bench, the time when the seven sisters come to confide, the time of the Mother of Stories, the time of the mirror, the time when the Great Midnight God bathes, and so on. These times revolve around George the Bench, or rather, they are based on George the Bench’s observations and feelings. George the Bench also has his own life story, and each of the related beings naturally has a timeline outside the square. Even the alien Casabrandos (plural) have a time in another time and space. Simply put, time in this story is multidimensional. So, why is it so difficult for us to recognize this? Because it’s like the Great Midnight God’s wings: “Those enormous wings are used to fly through future time and space, from one future to another. Are there other Great Midnight Gods? Of course there are, but we can only see one at a time.” Similarly, in the book, only one Casablanlan (singular) can be seen.

Ponti’s magical setting for this square adds another layer of mystery, a sense of parallel time and space—“When people enter, they transform into their favorite stuffed animals or dolls from childhood.” This might leave readers wondering whether the people involved are aware of the stuffed animals’ secret lives. Sometimes, they might know. For example, Anaïs P. should know, otherwise she wouldn’t always lend her doll to the little girl who needs to become stronger. But sometimes, it doesn’t matter. For example, at 1:00 a.m., when the rain of tears falls, Mr. Habissa Pekerou may not be aware of the stuffed bear weeping by the pool of tears. He leaves feeling relieved, and that’s enough, right? And at 10:10 a.m., when the seven sisters are sharing their story, neither they nor their dolls care. Seven means the same thing, and their happiness has been multiplied sevenfold. Who cares? However, the most melancholy moment is at 1:07 p.m., when Nuer Bear and Erdo embrace on a bench. Their owners are unaware: “The secret of their lives is that they never knew each other, yet they always loved each other.”—What a pity! But perhaps this is also the regret of many people’s life?

Doesn’t Fermín Térão’s (6:48) seemingly brilliant life epitomize many modern people? He achieved such remarkable success at such a young age, living an efficient life to the point where he could “sleep, eat, and pee while running”! Yet, he completely lost his sense of direction. No matter how fast he ran, he would always end up back where he started. Even his house would fly away out of boredom… From a certain perspective, isn’t life a bit like a maze? Those trapped within it can never see the full picture, and may not necessarily find the center or the exit—“I don’t know the true face of Mount Lu because I am within it.” Casabrando, from outer space, flew even faster, “the spacecraft moving at the same speed as my thoughts.” Yet, they constantly “forget” as they “find” something, which seems to embody a nearly absurd logic:Too fast a speed is equal to a complete stop.

The Garden of Forking Paths

In an interview, Pontet explained that after the publication of “George the Bench,” the director of the landscaping department of the city of Nantes, France, was so impressed by the book that he wanted to incorporate the concept of “George the Bench” into the botanical gardens of Nantes. Consequently, he was invited to participate in an art project related to the botanical gardens, which lasted nearly four years. He created a series of sculptures, art installations, and other small works within the gardens. I can’t help but wonder if a physical magic square were actually designed, it would be very popular. But from another perspective, could this picture book be a paper “maze” game designed by Pontet for readers?

As I read it for the umpteenth time, I suddenly remembered a short story collection I’d read in my youth, “The Garden of Forking Paths” by Borges. I don’t know why, but I dug it out and reread it, returning to “The Library of Babel,” included in the collection, and, of course, the final story, “The Garden of Forking Paths.” For me, Ponti’s enchanted square is the very embodiment of Borges’s fairytale-like labyrinth. The abstract, cosmic reflections of Borges’s novels are expressed in a visual, fantastical way in Ponti’s picture books, evoking a similar sense of “infinity” and “unknown possibilities.” Visually, “George on the Bench” uses layered details and exquisite composition to present a dynamic, complex world, much like Borges’s vision of a “labyrinth of labyrinths.” Together, they convey a core idea:The world we live in is multi-layered, and each layer holds endless possibilities..

Albert, the sinologist in Borges’s novel, said:“The Garden of Forking Paths is a vast riddle, or parable, the solution of which is time; and this obscure reason does not permit the word time to appear in the manuscript.”

“George the Bench” can also be seen as a huge riddle or fable. Although it uses time as a clue, if you go back to the front endpapers, you will find that the clock on the clock tower in the picture has no hands (time has been erased); although the book marks many time points of the day, it never explains what day it is!

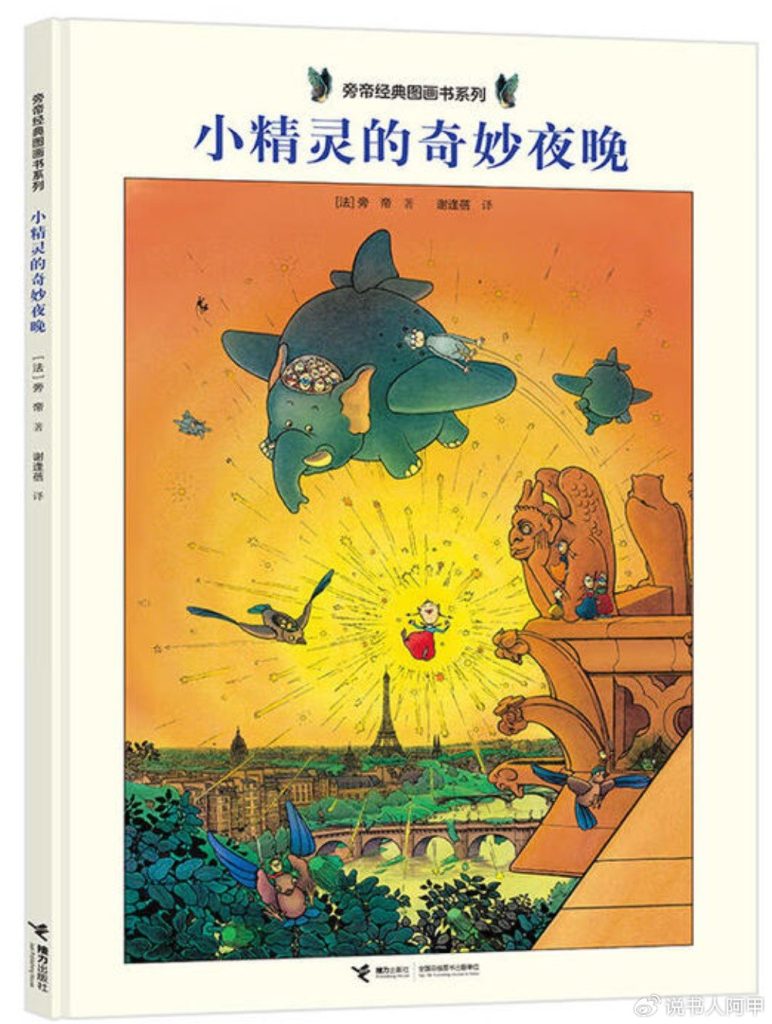

Ponti may have been fascinated by “time” since he was a child. He always proudly introduces his father as a “chrono-analyseur” from Italy. In fact, he was a special position in the Pompeii Steel Plant, responsible for measuring the time required for workers to complete tasks in order to optimize production processes and efficiency. I believe that part of the inspiration for “George the Bench” must come from Ponti’s fascination with “time”. He also has a strange description of time in “The Wonderful Night of the Elves” published in 2006. The whole story takes place in “Between 12:05 am and 12:05 am”.

I can’t be sure whether Bonnie was influenced by Borges, but read the imagination of the maze in the novel -

“I imagined it to be vast, not just a collection of octagonal pavilions and winding paths, but composed of rivers, provinces and kingdoms… I imagined itA maze of mazes, an intricate, ever-evolving maze that encompasses the past and the future, and in a sense even involves other planets.”

In fact, the maze revealed in the novel is actually “that chaotic novel” (claimed to be written by Peng Yu, a retired governor of Yunnan in the Qing Dynasty), the creator:

“It is believed that there are countless series of time, diverging, converging, and parallel times weaving an ever-growing, intricate web. This web of times that converge, diverge, intertwine, or remain forever undisturbed encompasses all possibilities.Most of the time, we don’t exist; at some times, there is you but not me; at other times, there is me but not you; and at still other times, both you and I exist.”

——This seems to be the best philosophical commentary on “George of the Bench”.

Of course, this could be pure coincidence: a short story written in 1941 and a picture book written and illustrated 60 years later, simply coincidentally sharing similar themes. The plot itself is bizarre. The protagonist, Yu Zhun, is a descendant of Peng Yu and a German spy during World War I. He is deeply grateful for the research and unreserved sharing of his ancestor’s mysteries by the sinologist Albert. However, in order to promptly inform the Germans of the location of a British artillery position in the northern French city of Albert, he is forced to shoot the man and allow himself to be arrested so that he can pass the news of the murder to headquarters via news reports—because the sinologist’s surname happens to be the same as the city’s name (just pronounced differently in French and English)! Well, what a desperate coincidence.

But wait, what’s the name of the magical square where George the Bench is located? Albert-Duronquarré. Another “Albert”? What a coincidence! Is it really just a coincidence?

Ajia, Written in Beijing on February 15, 2025