Japanese manga artist, picture book writer, and poet Yanase Takashi (やなせ たかし,1919–2013) and his creation, Anpanman, are unique figures in the world of children’s books. These works have brought warmth and moved generations, and their stories reveal the moving life of a creator deeply traumatized by war and a pursuit of love and justice. For readers both young and old, his works and his life are worth savoring.

The “Anpanman” series currently available to Chinese readers includes three sub-series: Anpanman Adventure Picture Book, Anpanman Picture Stories, and Anpanman Classic Storybook, totaling 25 volumes. However, this represents only a small portion of the complete Anpanman universe. The full roster includes over 500 books alone, as well as numerous spin-offs such as animation, movies, and games. There are even five “Anpanman Children’s Museums” in Japan! The “Anpanman” animated series, which premiered in 1988 and remains incredibly popular, has countless fans in mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. In 2009, when it surpassed 1,000 episodes, it even broke the Guinness World Record for the most characters in an animated series, with 1,768 characters appearing!

The slightly weird “Anpanman”

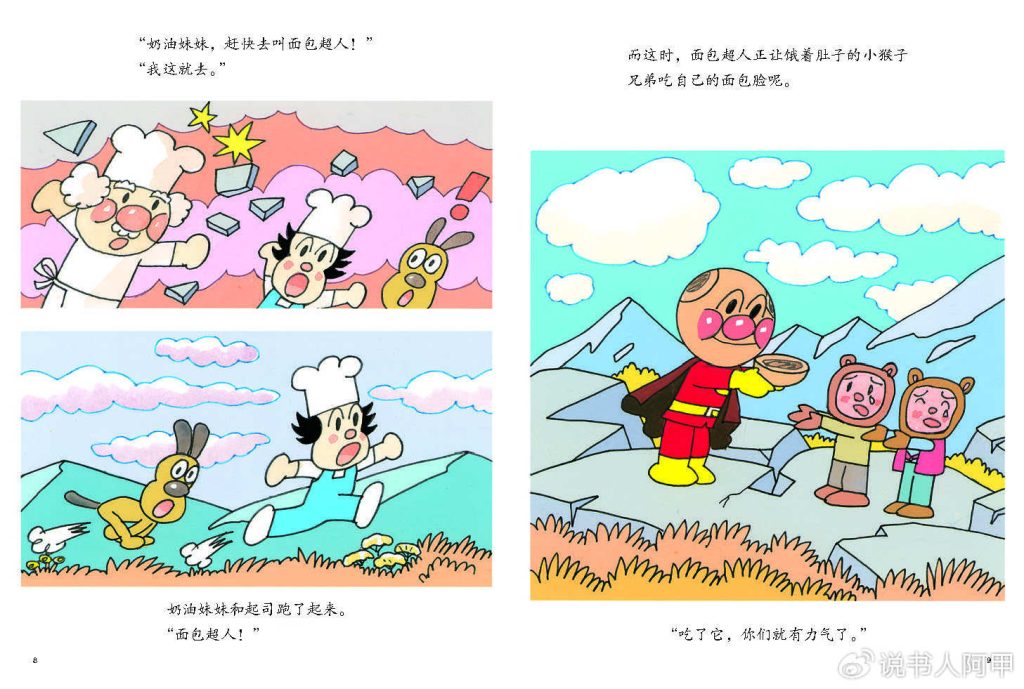

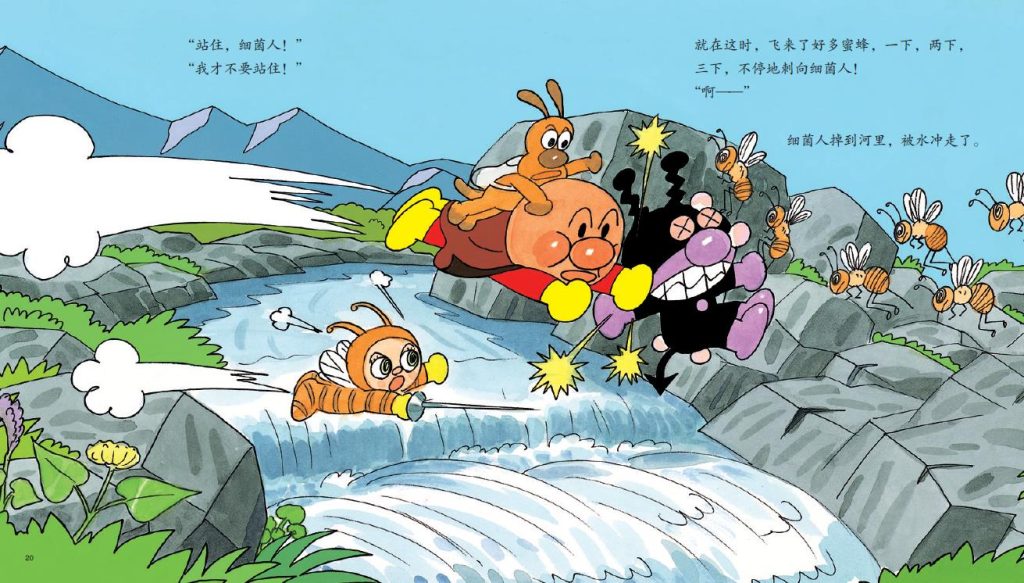

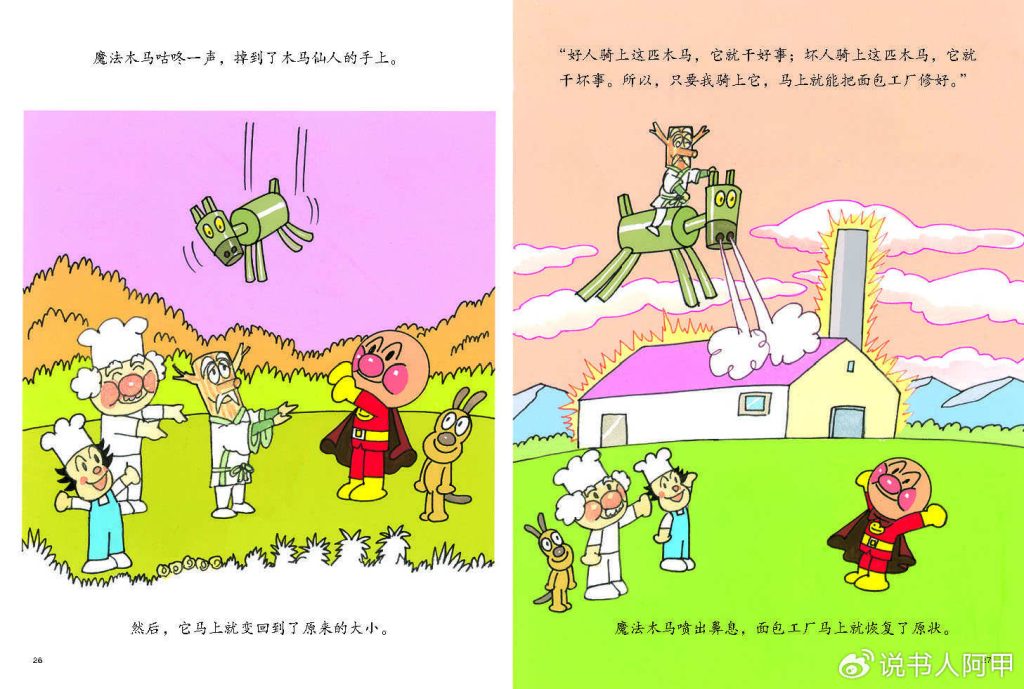

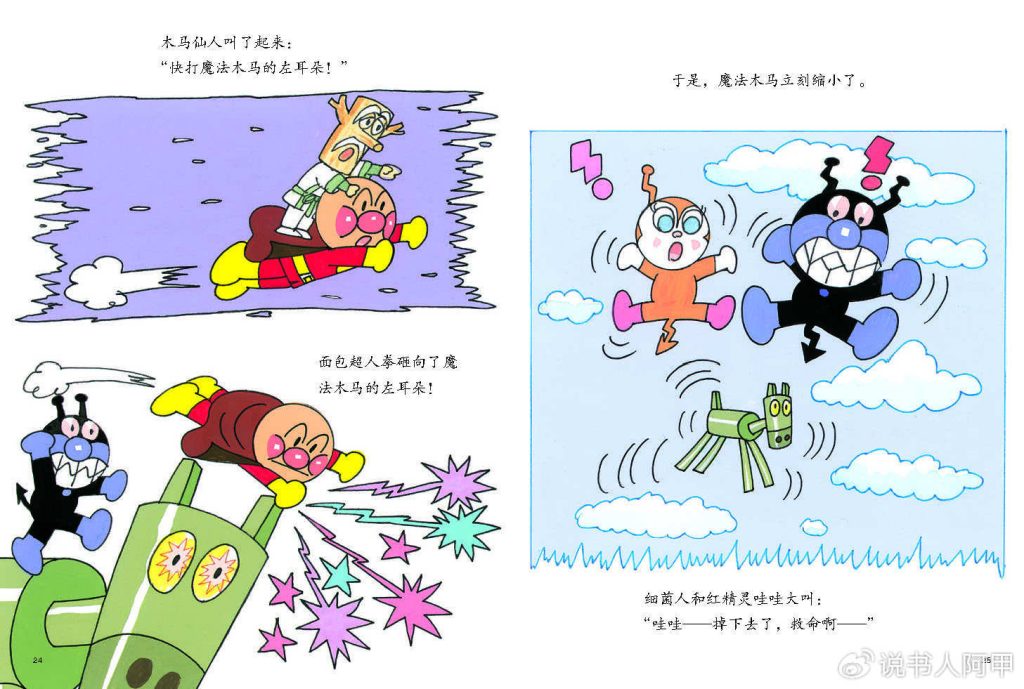

For many adult readers, it’s undeniable that at first glance, Anpanman appears a bit peculiar. In hundreds of picture books and anime stories, and across over 1,600 episodes, Anpanman, a man with a round, red bean-covered face and a patched cape, flies about. However, his abilities are limited, or often limited, because he unhesitatingly offers a helping hand to those in need and hunger. His method is straightforward: he tears off a piece of his own face and feeds it to them. While this sacrifice can be debilitating, he never regrets it, always welcoming every opportunity to help others with a smile. A torn face, wet, or dirty face can weaken Anpanman’s powers, and in severe cases, even cause him to fall from the sky. He often needs to wait for the rescue of Uncle Jam and his companions, who craft and attach a new face, before he can regain his powerful powers and defeat his arch-nemesis, the Germs. What’s more interesting is that the villain Bacteria Man can only be defeated but never killed. He can always escape safely after saying “Bye-bye Bacteria”, and he will gradually have more helpers like the Red Elf and the Elves who are keen on playing pranks.

Yanase Takashi’s concept of Anpanman “tearing off his face and eating it” has irked some adult readers and viewers, and this has often been the subject of criticism on Chinese social media. In fact, as early as the 1970s, when the first Anpanman picture book was published, Japanese adult readers and book reviewers also received a number of similar negative comments, saying that “the plot is too gory.” Some “experts” also criticized the plot as vulgar and unsuitable for library shelves, fearing it would corrupt children. For a while, even the editors at the publishing house begged Yanase to stop including Anpanman with a torn face in his picture books. However, it gradually became apparent that young readers were enamored with Anpanman, and Anpanman became so popular in kindergartens and libraries that a frenzy of demand for copies of the book developed. One father told Yanase Takashi that his son loved Anpanman so much that he read it over and over again, and he could recite it by heart! Yanase Takashi lamented that “children are the most unforgiving critics,” and he continued to write new Anpanman books. By the time it was adapted into an animated series in 1988, this somewhat eccentric Anpanman had already become popular.

The core story of Anpanman

Some people forcefully link the concept of “giving away body parts for others to eat” to Japanese culture, but this is completely unnecessary. Aren’t Chinese people also familiar with Buddhist stories like “giving oneself to feed the tiger” and “cutting flesh to feed the eagle”? The borrowing of this concept in the plot of Master Yideng rescuing Huang Rong in Jin Yong’s martial arts novel “The Legend of the Condor Heroes” was readily accepted by readers, right? In another cultural context, the ritual of breaking bread for believers also symbolizes sacrifice for the salvation of humanity. Therefore, Anpanman’s tearing off his face for others to eat is also a continuation of a great ideal, the spiritual core of which lies in:The ultimate in compassion, self-sacrifice, and selfless devotion.

Anpanman is the embodiment of justice and warmth. His bread-faced face not only symbolizes sharing and giving, but also serves as the source of his strength. Even when his own face is given to someone in need, he can regain his strength with a new bread-face made by Uncle Jam. This cycle is more than just a story setting; it also conveys an important concept:Selfless giving and the cycle of love can bring infinite vitality and kindness.

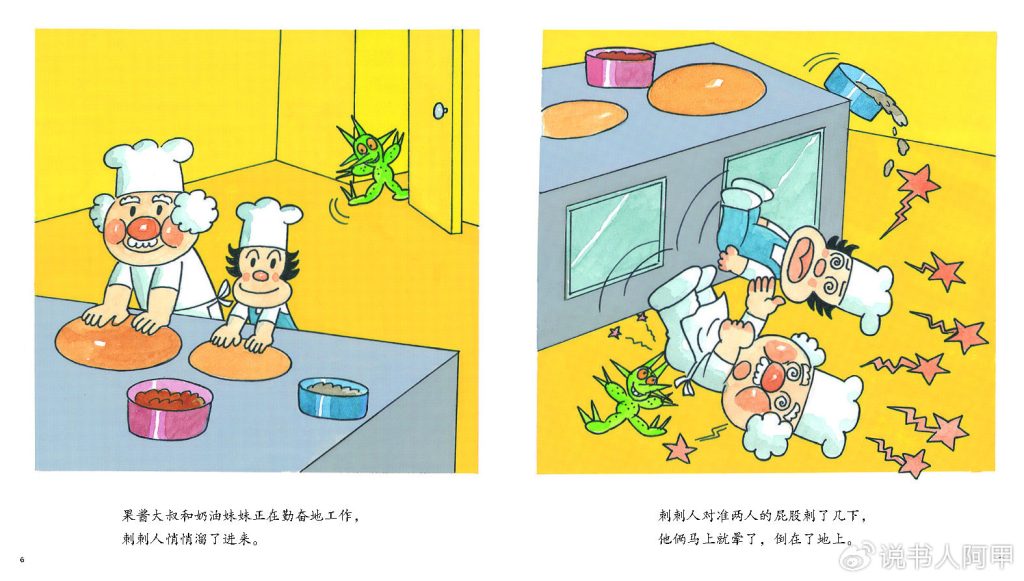

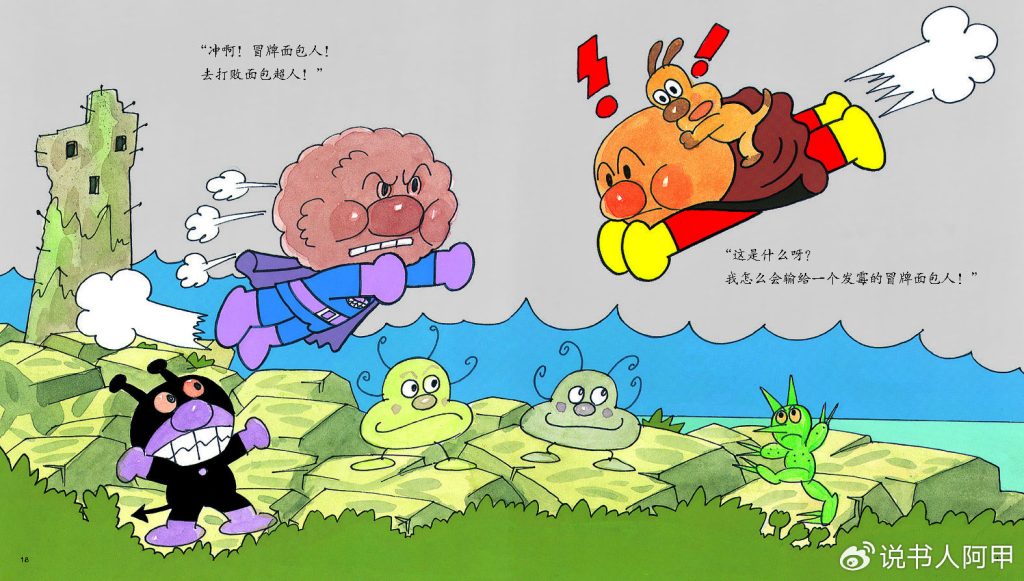

Take “Anpanman and the Prickly Man” for example. While Anpanman is out helping others, a strange old man arrives at the bakery. Seeing the old man unable to walk due to hunger, Cream Sister offers him a freshly baked loaf of bread, and the old man returns the favor with a small cactus. It turns out that the Prickly Man, transformed from the small cactus, is a spy planted by the Bacteria Man. After wreaking havoc in the bakery, he packs up the secret flour used to make Anpanman. The story continues as usual: Anpanman returns to the bakery, donning a new face, tracks down the Bacteria Man’s lair, and engages in a life-and-death duel with the fake Anpanman. Interestingly, it’s the Prickly Man who ultimately pierces the fake Anpanman, causing the explosion. While this wasn’t intentional, the Prickly Man still manages to pierce the fake Anpanman’s face. The explosion pierces the thick clouds, allowing sunlight to disperse the Bacteria Man and the Mold Imp.

Yanase Takashi creates an endless cycle of selfless giving, self-sacrifice, and heartwarming love in his stories. All those who side with Anpanman are “infected” by his naivety, becoming somewhat foolishly, indiscriminately, and unrequitedly helpful, even if it means falling prey to his enemies. However, this foolish, selfless sacrifice always leads to a kind of “resurrection” when their superpowers are regained, making them even more powerful. Enemies, on the other hand, become less formidable, their mischief more like pure pranks, even creating endearing and hilarious side effects. For example, the mischievous Spiky Man ultimately performs a significant deed, helping to disinfect the sunlight. The endless creativity of Bacteria Man’s “evil deeds” creates suspense and intrigue in the plot, giving Anpanman more opportunities to demonstrate his strength. Consequently, Yanase Takashi is reluctant to see Bacteria Man eliminated, constantly recruiting helpers to escalate his mischief.

As Laozi said, “When all in the world understand beauty to be beautiful, then ugliness exists. When all understand goodness to be good, then evil exists.” In this sense, bacteria people, as representatives of “negative energy”, are so important!

Diverse characters present a rich world of human beings

If Anpanman and Bacteriaman are the two most opposing positive and negative poles in the story, then the various complex characters in the “Anpanman” series are the supporters of these two poles, or the diverse existences that wander between the two poles. They make the world of Anpanman more three-dimensional and full, and more warm and touchable.

“The Birth of Anpanman” traces the origins of this peculiar superman, whose powers range from the “weak” to the “superpowered,” primarily due to the loving bread face made for him by Uncle Jam and Sister Cream. Anpanman may have been a meteor from outer space, arriving on Earth with a strange egg, who happened to crash-land on a bacterial island and became a bacterial man. They’re a pair of natural enemies.

In addition to the family-like team of Uncle Jam, Sister Cream, and Puppy Cheese, Anpanman also has allies such as Toast Man, Curry Bread Man, Melon Man, Cream Bread Brother, Rice Ball Man, Fried Shrimp Rice Man, Fried Pork Cutlet Man, and Mixed Pot Man. It is obvious that they are all necessary for the diversity to enrich the food culture, and these daily delicacies are obviously good. They also have the support of many small animal characters.

On the Bacteria Man’s side, besides his constant companions, the moldy imps, he also boasts distinctive villains, such as the Red Elf, who constantly plays mischief with him, and his sister, the Blue Elf. These villains likely hail from the Bacteria Planet and have come to Earth with a mission to cause trouble, presumably to make food like Anpanman moldy. Therefore, their trainer, the Bacteria Sage (see “Anpanman and the Magic Brush”), is relatively neutral. He seems to harbor no ill will towards Anpanman and even urges the Bacteria Man to study with the brush, rather than “making trouble.”

The Red Elf is a most intriguing creature. She’s incredibly headstrong and prone to mischief, yet she also possesses a remarkably gentle and endearing side. The Bacteria Man is devoted to her and obeys her every command, but she’s obsessed with the righteous Toast Man and won’t tolerate him even slightly harming her idol. So, is the Red Elf good or evil? In fact, there are even more complex characters in the anime, such as Spiral Anpanman and Black Spiral Anpanman, who possess dual personalities of both good and evil. Under certain circumstances, they can be seduced by the Bacteria Man and temporarily become accomplices of evil. Doesn’t this also mirror the complexities of human nature?

The Birth of Anpanman

The first “Anpanman” picture book appeared in 1973, but the character actually appeared earlier in Yanase Takashi’s collection of short fairy tales for adult readers, “Twelve Pearls” (published in 1970), and first in his radio dramas. Yanase Takashi was 54 when he drew this seemingly “weak” Superman into the picture book, and most of the subsequent Anpanman stories were written after he entered his sixties and seventies. Since he and his wife had no children, they treated Anpanman as their own child, preferring to be known as “Anpanman Grandpa.” In these simple and cheerful stories, drawn in a seemingly “old-fashioned” manga style, this storytelling grandfather imbues himself with the profound insights of his life.

In his youth, he served in the military and endured starvation. After retiring, he worked as a designer, drew comics, wrote poetry, and edited radio dramas. By chance, anime master Osamu Tezuka asked him to be the art director for the animated film “One Thousand and One Nights.” Following its huge success, Tezuka personally funded the adaptation of a recent radio drama, “The Gentle Lion,” into an animated film. After the award-winning animation, Yanase Takashi adapted it into his debut picture book.

“The Gentle Lion” was translated and introduced to China in 2003. I was deeply impressed by it. It tells the story of a lion raised by a mother dog, reportedly inspired by a true story at a German zoo. However, Yanase Takashi’s focus is on the lion, who grows up to become a superstar, escapes his cage, returns to his aging mother dog, and tragically dies at the hands of a human gun. Although the author offers an imagined happy ending, the tragic scene is truly more shocking. Yanase Takashi does not shy away from conflict and violence in his picture books, but he uses extremely exaggerated cartoon techniques to highlight the folly and absurdity of violence. Readers are deeply moved by the interspecies warmth and kindness expressed in this story.

Inspired by the success of “The Gentle Lion”, Yanase Takashi began to create the “next” story at the strong invitation of his editor, and this story he was going to tell for himself, to tell his own story. At that time, the whole world was popular with the “superman” culture, and Japan was also deeply influenced. “Astro Boy” created by Osamu Tezuka was a more sci-fi image of a young superman. Yanase Takashi was obviously also affected and inspired by something, but the “superman” in his mind was not proud of his superpowers, and his concept of justice was not so “high-end”, but very simple, simple, straightforward, and its universality could even be applied to the so-called “enemy”. In Yanase Takashi’s view, “Justice is not about talking big, but about handing a piece of bread to someone who is starving.This is the true meaning of the Anpanman spirit, and it is also the profound understanding that Yanase Takashi gained from the twists and turns of his first half of life.

Insights from complex life experiences

Born in 1919, Yanase Takashi (柳濑嵩) came from a well-off family. Both his parents came from prominent families in Kochi Prefecture, and the Yanase family had been hereditary local officials with a 300-year-old tradition. His father, Yanase Kiyoshi, was a journalist with a passion for literature and art. In his youth, he traveled extensively throughout China and fell in love with Mount Song (嵩) in Henan, hence the name “Song” (嵩) for his eldest son. However, life is unpredictable, and when Yanase Takashi was five years old, his father died en route to Xiamen, where he was serving as a clerk.

The mother had no choice but to first adopt her youngest son, Chihiro, to her late husband’s older brother, and later sent Yanase Takashi to foster care. This uncle was a rural doctor and also loved literature. He and his wife loved the two little brothers very much and treated them as their own children. However, the pain of separation from his mother was always lingering. Yanase Takashi later wrote a poem “The Day Mom Left”, in which he wrote:

One day

We were separated from our mother.

Mom said our health is not good

I want to be treated at my uncle’s house who is a doctor

……

Yanase Takashi, who finally did not wait for his mother, reached adolescence and once ran away from home and even attempted suicide by lying on the railway tracks, but fortunately he escaped before the gates of death.

Yanase Takashi struggled academically, but his passion for drawing led him to strive for admission to the Tokyo Higher School of Technology, where he found a satisfying job as a graphic designer. However, his good fortune didn’t last long. He soon received his draft notice. After enduring a grueling boot camp and two years of service in Japan, he was assigned to an artillery regiment, tasked with creating and deciphering cipher codes. He was then unceremoniously stationed in a rural area of Fuzhou, China.

During China’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression, Yanase Takashi’s regiment remained idle for two years, perhaps due to misjudgment and poor scheduling by his superiors. Due to the isolated region, the locals were unaware of the war unfolding outside. Bored, Yanase Takashi applied for a promotional role, connecting with the locals through comics and storytelling. The success was remarkable, and it paved the way for his future career as a manga artist.

It was only as the Pacific War neared its end that Yanase Takashi truly felt the brutality of war. His artillery regiment was ordered to the Shanghai front. They carried their baggage on foot for nearly six months, nearly dying of illness along the way. Even more horrific was the hunger, which kept him on the brink of death for months. Perhaps it was this experience that made him think deeply about the profound connection between hunger and justice. Halfway through his unit’s journey, they learned of Japan’s surrender, and he thought, “Finally, I can go home.” And so, the young man was unknowingly sent back to Japan. Upon returning home, he learned that his younger brother, Chihiro, a top student at a prestigious university, had been killed in action. In reality, his brother had been aboard a warship that had been sunk by bombs.

Such a painful and absurd experience left Yanase Takashi deeply confused: What were he and his brother fighting for? Was it justice? What exactly is justice? He later wrote in “Anpanman’s Last Letter”: “There is no such thing as ‘fighting for justice.’ ‘Justice’ can suddenly change, even be completely reversed. ‘Justice’ is unbelievable.” Life experience has made me fully understand this truth, and it has become the foundation of my postwar thinking.The true and unchanging justice is love and sacrifice.”——This is exactly the starting point of “Anpanman”.

Anpanman March

Here, I would like to express my special thanks to the picture book creators and translators from Taiwan -Xu Shuning.The content introduced above refers to her long article- Anpanman’s Song of Justice (serialized in Cosmic Light Magazine from September to November 2022).What I benefited most from this long article were the quotations from original works that don’t yet have Chinese translations. For example, I learned that Yanase Takashi’s theme song, “Anpanman March,” actually has a first section, which is usually omitted in the current versions of the anime. Here’s Xu Shuning’s “tentative translation”:

Yeah, how happy.

Living is joy even if there is pain in the heart

Why live and what to do

Never live your life in ignorance

Live this moment with a burning heart

Please go forward with a smile

…

Whether it is the Cantonese or Mandarin version of the cartoon, only the latter part is retained. For example, in the Cantonese version, the main part of the opening song is as follows:

What is your happiness?

What do you need to do to be happy?

It’s over without me knowing it

I don’t want to be like this.

Don’t forget your dreams

Don’t shed tears

So you have to fly high

Even if you are at the ends of the earth

Yeah, don’t be afraid.

For everyone

Only with love and courage

Ah Anpanman

You are so gentle

To protect everyone’s dreams!

The Mandarin version has some minor translation changes, and its core sentence is:

Come on, for everyone

Don’t be afraid anymore

Love and courage are your friends

Perhaps, from the adult perspective of some directors and editors, statements like “To live is joy, even if one’s heart is wounded” and “Why live, what to do” seem too heavy for young children and too confusing for adults accustomed to peace and quiet. Yet, these are indeed the strongest insights and questions Yanase Takashi brings to the story of Anpanman. It’s worth noting that after the Great East Japan Earthquake in March 2011, someone requested a song for those hardest hit by the disaster. Amidst the devastated ruins, the full version of “Anpanman March” came over the radio. The bright melody and profound lyrics instantly brightened the hearts of countless people. Those who had experienced this devastating change suddenly understood Yanase Takashi’s message: to smile and regain the courage to “live in the moment.”

There is also a Japanese scholar, Kazuo Kumada, who published an academic paper in 2014, “The Loneliness of Anpanman: Love, Courage and Male Alliance” (アンパンマンの孤塵-愛と勇気とホモソーシャル-, published in “Human Culture: Bulletin of the Institute of Human Culture, Aichi Gakuin University”, September 2014), discussing the deep sociological significance of this march. He specifically mentioned that this song might have been written by Yanase Takashi for his younger brother who died in vain in the war. Because the younger brother did not want to join the Kamikaze Special Attack Force, which was like committing suicide, but was forced to sign up as a “volunteer” under pressure from his male “comrades”. Therefore, this scholar believes that,The “Anpanman” created by Takashi Yanase is actually a lonely brave man. His selfless and fearless choice does not come from any external pressure, but belongs only to himself and comes only from his deep understanding of justice.The most important line in the lyrics, the core meaning is:Love and courage are your only friends.This may be the most crucial point of Anpanman’s “values of justice”.

Half a century has passed since the first Anpanman picture book was published, and this less-than-superpowered “superman” seems even more enduring. Its stories are universally appealing and heartwarming, written in simple, accessible language and illustrated in a vibrant and engaging style. For children, it’s an introduction to love and courage; for adults, it’s a profound allegory for reflecting on the meaning of life. Yanase Takashi never neglects the wisdom of childhood in his work, firmly believing in children’s capacity for profound understanding. It’s for this reason that the seemingly simple Anpanman story touches upon the deepest aspects of human nature.

However, a good story is one that you just enjoy. As Yanase Takashi said in the afterword of Anpanman and the Prickly Man, “Please don’t delve into the reasons, just read it and enjoy it.”

Ajia, Written in Beijing on February 12, 2025