Continued from the previous chapter:Artists Telling Stories for Children (Part 7)

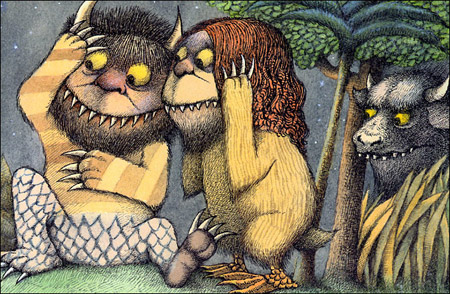

“Staring into their yellow eyes without blinking” (still from the movie “Where the Wild Things Are”)

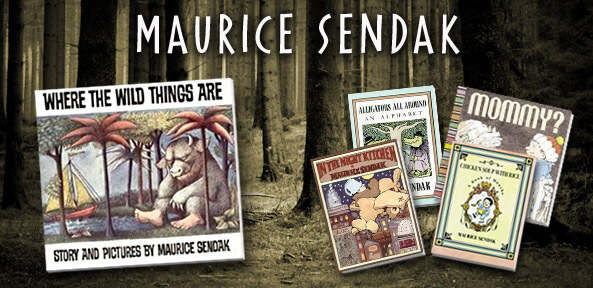

Where the Wild Things Are

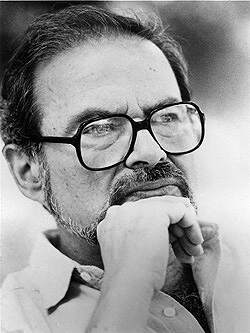

Maurice Sendak

It’s hard to describe a creator like Maurice Sendak (1928-) with anything but mild words.

When Sendak’s masterpiece “Where the Wild Things Are” was first published in 1963, the famous editor, Ms. Ursula of Harper’s Publishing Company, praised it as a masterpiece.“The greatest masterpiece“Later, Mr. Aiden Chambers, a famous British children’s literature writer and reading expert, said“Because of this book, picture books have become adults.”

In 2010, when the movie “Where the Wild Things Are” adapted from this picture book was released, Sendak and his works once again aroused heated discussion. Americans generally believed that:Sendak, as a picture book artist, changed our understanding of childhood.

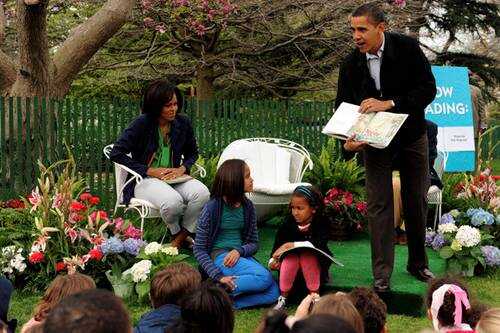

Current US President Barack Obama has repeatedly spoken of his childhood love for Where the Wild Things Are, believing the book’s protagonist, Max, to be akin to himself. Sendak gifted several signed copies to Obama’s two daughters. At a 2009 Easter celebration on the White House lawn, Obama read from the book to an audience of children and adults. Before reading, he casually asked, “Has anyone read this book?” The audience responded in unison, “Yes!”

Obama read from “Where the Wild Things Are” on the White House lawn on Easter Sunday 2009

However, since the 1960s, many adults have expressed strong objections to Sendak’s work, complaining that the illustrations are too dark, that the monsters in the books would frighten children, or that the mother’s punishments would cause psychological trauma. When the sequel, Kitchen Night Rhapsody (1970), was published, some were shocked by the inclusion of a naked little boy—leading to this equally wonderful picture book being banned from sale in some regions or from children’s libraries for a long time. Sendak completely ignored these negative reactions and focused solely on his work. When the third volume of the trilogy, In That Faraway Place (1981), was published, some were even more shocked by the inclusion of a naked baby girl!

Kitchen Night Rhapsody insert

Sendak once said that the three people in the book were going to

The image of the chef who brought in the bread was based on Hitler’s image.

This is related to his childhood impression of the Nazi Holocaust

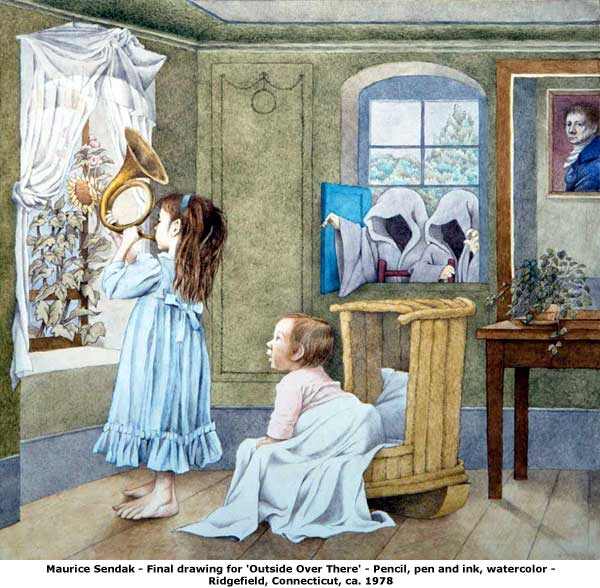

Insert from “In That Faraway Place”

In fact, Sendak intended to engage in a certain kind of “subversion” from the very beginning. Today, it seems that this subversion was very successful, winning him multiple Caldecott Medals, the International Hans Christian Andersen Award for Painter in 1970, the inaugural Lindgren Memorial Award in 2003 (currently the most prestigious award in the world for children’s literature), and the National Medal of Arts awarded by the United States Congress in 1996.

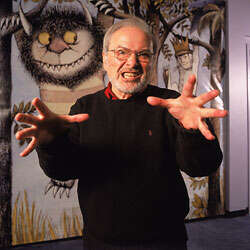

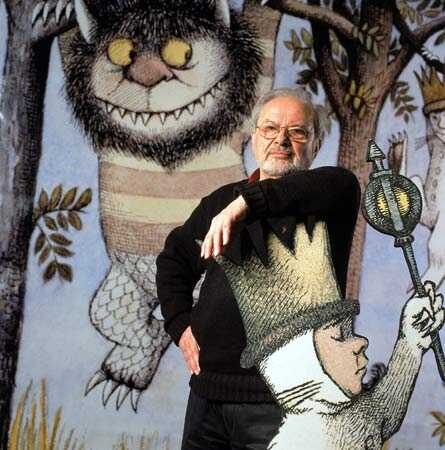

Photo of Sendak at age 80 in 2008

But Sendak’s pursuit went far beyond these accolades. Following his 80th birthday celebration in 2008, he gave an interview to The New York Times, recounting the masters who had profoundly influenced his life: Mozart, the musician; Blake, the painter and poet; Melville, the novelist; and Dickinson. He admitted that he wasn’t one of them, but he longed to be as unique as they were, to create works that had never been attempted before. He said he was now quite afraid he wouldn’t have the time to complete such work. He simply hoped to create something that would touch someone in the future, just as Mozart, Keats, Dickinson, and others had inspired him.

Stills from Where the Wild Things Are

So, how was a genius like Sendak forged?

Sendak in his youth

It is said that the prototype of the puppy in “Where the Wild Things Are” is his childhood playmate.

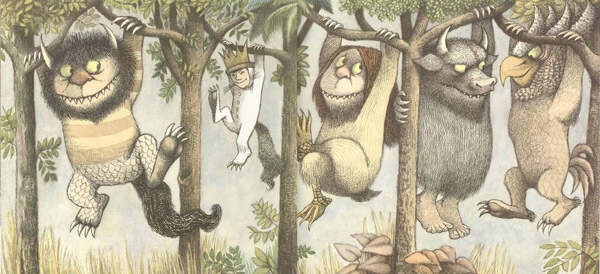

Born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1928, during the early years of the Great Depression, Sendak was born into a Polish-Jewish immigrant family. His father was a tailor. Their home was small, but they had many relatives, and their mother had a bad temper. Later, more and more relatives fled from Europe, but most of those who didn’t escape died in concentration camps. Sendak was a sickly child, and early on he experienced the threat of death. He was often confined to his bed, with only books and solitary dreams for company. However, his father would come to tell him stories, mostly from the Bible—in short, ancient tales from ancient times. These stories would later become the main source of inspiration for Sendak’s picture books. The relatives who visited Sendak struck him as both affectionate and somewhat abrasive. Their large bodies squeezed into the small space often made him feel suffocated. One uncle, in particular, made harsh comments about him, which he deeply resented. They all became the models for the wild beasts in “Where the Wild Things Are.”

The image of the beast in the book

A poor family, a host of poor relatives, the Great Depression, the Nazi genocide of Jews in Europe, and racial discrimination in the United States—all these factors combined to create the environment in which Sendak, a Jewish child in the United States, grew up. After graduating from high school, Sendak began to earn a living, decorating windows for a toy store and children’s bookstore while continuing to study art at night school. He was almost entirely self-taught in painting, but he also had a voracious love of reading from a young age. Although he never attended university, he was well-read and possessed a vast knowledge of literature and art. He also had a keen interest in socializing with intellectuals. He had an unusual close friend, Eugene Glynn, a renowned psychoanalyst, who undoubtedly enriched his knowledge of psychology.

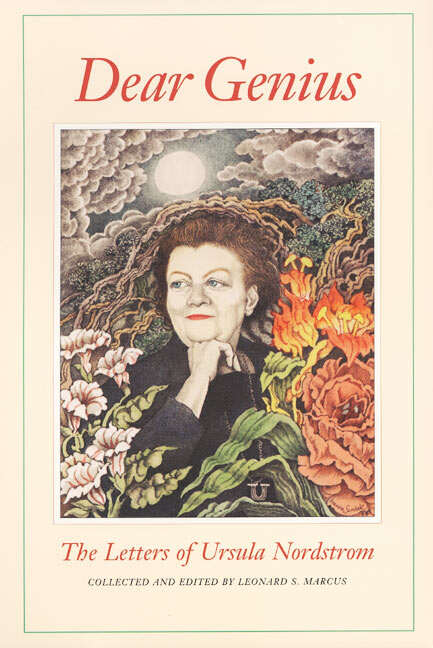

Ms. Ursula’s collection of letters, “Dear Geniuses,” can be said to be a treasure trove for children’s book editors.

This book collects the most glorious years of Ursula’s children’s books at Harper’s Company.

Correspondence with her gifted writers and painters

The correspondence notes with Sendak can be seen——

[Reading Notes] Letter from the Editor of Where the Wild Things Are to the Painter

By the way, the cover illustration of this book was drawn by Sendak himself.of

In the 1950s, the fledgling author Sendak met editor Ursula, who introduced him to the world of children’s books and facilitated his collaborations with numerous prominent children’s literature authors, illustrating their works. Before 1964, Sendak had won five Caldecott Medals for his illustrations for authors. While this might have been a high honor for others, Sendak viewed it as simply a learning process. As early as 1955, Sendak began conceiving what he considered a “real picture book,” titled “Where the Wild Horses Are.” He had high hopes for this work, considering his previous works to be mere illustrations. Ursula, upon hearing of his concept, strongly supported and encouraged its creation.

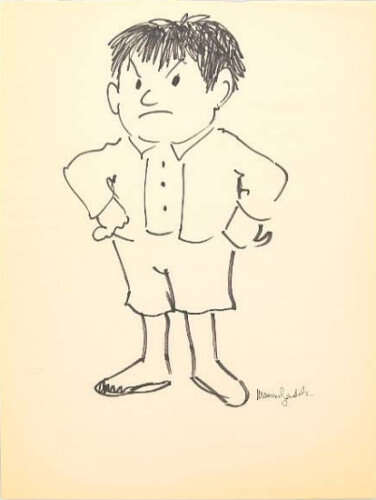

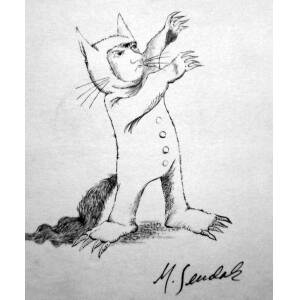

This is the original image design of the protagonist Max

Max’s finalized image

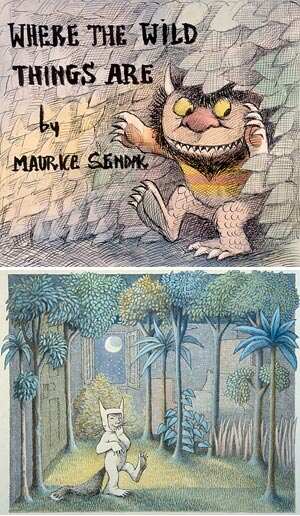

The exceptionally meticulous Sendak spent a full eight years to complete the work. “Wild horses” was later changed to “wild beasts.” The English term “wild things” doesn’t refer to wild beasts in general; it derives from a Yiddish insult for mischievous children. The story’s protagonist, Max, is a mischievous boy. His mother, angry and punishing him, locks him in his bedroom and denies him dinner. However, Max, overcome by a frenzy, enters a dream, where he travels to a place where wild beasts roam freely, leading them on a wild rampage. After venting his imaginary outburst, the child returns to reality to find his mother completely forgiven, and “dinner prepared for him in the room—still warm.”

The famous wild rumpus scene runs across the entire painting, without any words.

The only beast with human feet, some researchers believe that it is a metaphor for Max’s father.

Cover of the Chinese version of Where the Wild Things Are

This story, which delves deeply into children’s psyches, even their subconscious, was unprecedented before Sendak. The text and pictures in the story achieve a perfect integration, truly, as Matsui Naoki said, “expressing something difficult to express in words or pictures alone.” It provides a perfect model for the modern picture book, and over the past half century, countless papers and books have been devoted to studying “Where the Wild Things Are.”

But what kind of “surgery” did Sendak perform on his childhood?

The top half is the original cover design for Where the Wild Things Are

Children are often described as innocent, beautiful, and romantic, waiting to grow up in a simple, pure, and carefree state. Therefore, most works written for children are very happy and romantic, with some adult advice and lessons mixed in with the lively childish games.

Sendak seems to have a soft spot for monsters :)

But Sendak is different. He allows us to truly see the child’s near-manic state of mind, the often obscured, repressed, and tormented side. His Max is constantly fighting and struggling, turning to dreams in anger, even laughing with his hands covering his mouth, dancing, and sailing his own boat to the wild land, where he takes control of the situation and achieves self-realization in his fantasy, while also compromising with the mother he deeply loves and who deeply loves him, until he returns in the embrace of her love.

These are all drawn from Sendak’s own childhood experiences. He said: “Childhood has an endless fascination and attraction for me. If I have unusual talents, it’s not because I draw or write better than others — I never fool myself that way. It’s because I remember things that others don’t: sounds, feelings, and images — the emotional qualities of certain moments in childhood.”

The artists’ stories have come to an end for now, but there is still a little tail to go… »»

* * * * * * * * *

Tidbit 1: For details about my connection to Where the Wild Things Are and my somewhat limited summary of the reasons why I like this book, see:[Postscript] Why I Like Where the Wild Things Are

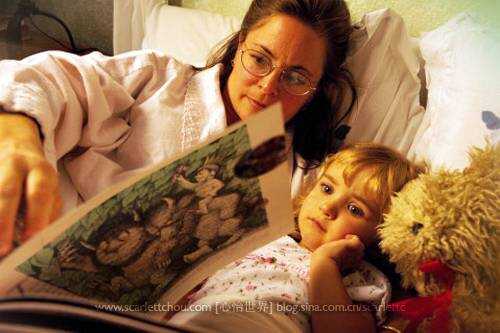

Shortly after the book was published, child psychologists wrote articles warning that it might frighten children. According to French-based illustrator Chen Jianghong, the book also caused concern among many adults when it was released in Europe in the 1970s. Fortunately, over the past half century, only a few slightly nervous children or adults (mostly adults) have been frightened, while the vast majority of readers have embraced it. In recent years, in various reading surveys in the United States, the book has consistently ranked first in the picture book category. The fact that children are not easily frightened is illustrated here:

Fun fact: For years, many people desperately tried to get this classic picture book adapted into a film, but Sendak refused to grant the rights. For some reason, he finally relented, and in late 2009 (46 years after the original 1963 publication), the film Where the Wild Things Are was finally adapted. Sendak’s approval for the film’s director, Spike Jonze (born 1969), likely wasn’t due to his record of blockbuster films, but rather because Jonze was a true Sendak enthusiast and quite eccentric. For example, he was a renowned figure in extreme sports and had a fascination with darker, more psychologically oriented material. In short, he was definitely not one for conformity or crowd-pleasing. Sendak was deeply involved in the film’s adaptation, production, and promotion, personally and deeply involved, even getting angry at anyone who dared to offer even the slightest criticism.

The film is certainly good, but it’s a completely different work from the picture book, and even seems to be a bit older. I think it’s more suitable for viewers over 9 years old, and not for young children.

Sendak discusses with the director on the set

Sendak poses for a photo with the director (center) and the lead actor (right) at the film’s press conference.

Movie poster one

One of the movie scenes

Movie scene 2 (the mother appears in the movie, she is a single mother)

Movie scene 3

Movie scene 4

Movie scene 5

Movie Scene 6

Movie Scene 7

Movie Scene 8

Tidbit 3: Finally, let’s go back to 1963.

That year, Sendak’s self-written and illustrated book, Where the Wild Things Are, was published. —“From then on, picture books became adults.”

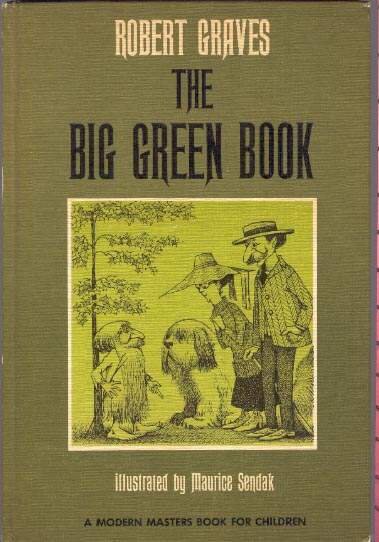

Just the year before that (1962), Sendak published The Big Green Book, a children’s novel illustrated by British poet and writer Robert Graves.

The Big Green Book cover

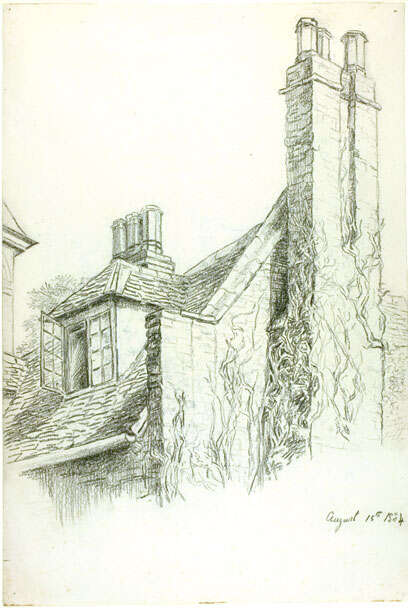

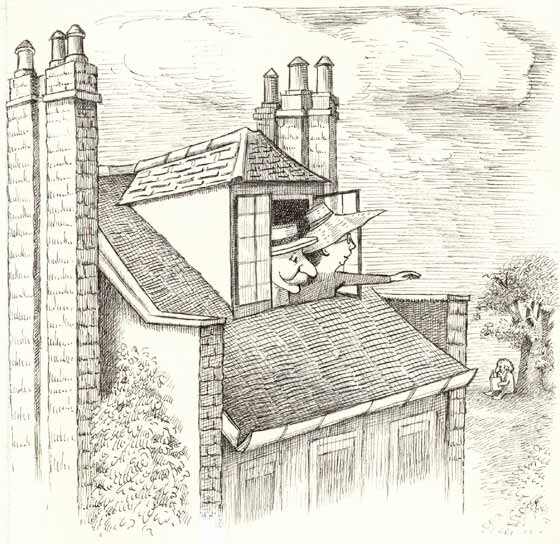

This is not surprising, but what is interesting is that many of the illustrations in this book are very similar to Beatrix Potter’s paintings in terms of material, composition and creativity. Of course, Sendak made corresponding adjustments based on the needs of the new story. But what is certain is that Sendak was deliberately imitating Potter in these illustrations -

Painted by Potter in 1884

Sendak’s illustrations from the book (1962)

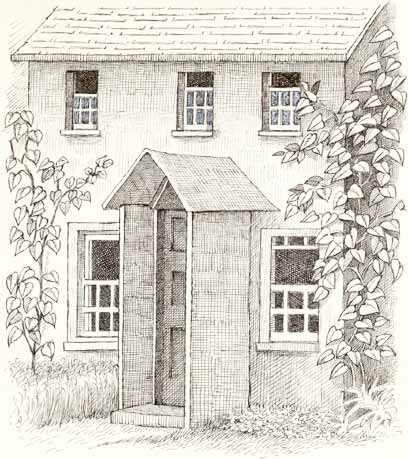

This, it turns out, was Sendak’s special way of paying homage to Beatrix Potter. Sendak deeply admired the “beauty,” “poetry,” and “vividness” of Potter’s paintings. He once marveled, “How could she (Potter) paint so well?”—a talent not all painters possess!

Miss Porter’s “Green House” at Hilltop Manor

Miss Porter standing in front of the door (photo taken in 1913)

One of Sendak’s illustrations for The Big Green Book (published in 1962)