Masters of the art of storytelling for children(one) (two) (three) (Four) (five) (six) (seven) (eight)

I finished this article, “Masters of the Art of Storytelling for Children,” just before Children’s Day. It was originally written at the request of a magazine seemingly unrelated to children’s books, but since it happens to be a topic I’m particularly fond of, I finally managed to squeeze some time out of my already limited schedule. Once again, there’s always time for what you enjoy.

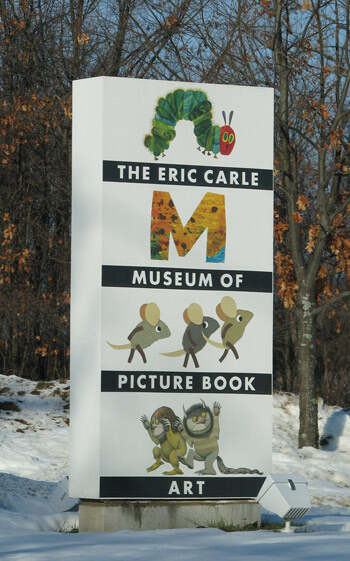

Initially, I had a rather ambitious list: Beatrix Potter, Mary Holly Eiss, Virginia Lee Burton, Leo Lionni, Eric Carle, Maurice Sendak, Dick Bruna, Janosz, Shel Silverstein, Dr. Seuss, Yoko Sano, John Burningham, Anthony Brown, David Wiesner—fourteen in all. Actually, all of them were picture book creators I happened to be familiar with (for those I wasn’t, please forgive my ignorance). They were all “self-writers”—storytellers, and I happened to know a little about the story behind one of their works that particularly touched my heart.

At first, I didn’t realize how huge this project was. I didn’t realize that it would take at least a day or two to sort out the information before writing each person’s short story, and then it would take another day or two to organize each person’s picture information. In comparison, the time spent on typing is negligible :)

Moreover, compared to typing, searching, organizing, and savoring the stories of these masters is so much more enjoyable in its own right. I often can’t help but wonder how happy it would be if I could just be lazy and be a reader… Finally, after finishing my work on Sendak, I’ve decided to call it a day. I’m really running out of time and energy. Haha, I’ll save the rest for next year.

I used the word “master” very carefully in this article; I wouldn’t casually assign it to anyone. I once heard guqin player Gong Yi explain the term, and I deeply agree. He refused the title, stating that he was simply an expert in guqin (so calling him a “guqin player” is perfectly acceptable). An “expert” specializes in a single task, such as selling tickets on a bus or at the entrance of a movie theater. After years of practice, they’ve mastered the art of performing, and that’s when they become experts. So, what constitutes a master? They shouldn’t simply specialize in a single skill or expertise, but rather possess a profound accumulation and cultivation of their entire lives. This might simply be the accumulation of countless seemingly trivial experiences, but when they suddenly burst into a unique light, they embody the entirety of life’s experience. As Yoko Sano said, “I can only say that I express and burn everything in my life in my work.”

Based on my current limited knowledge and careful consideration, I believe that the figures listed above can all be called “masters of picture book art.” When they tell stories for children, they truly draw on their entire life experiences. What is particularly amazing is not the superb skills of their art (which is of course beyond doubt), but the magical power they seem to possess, which allows them to communicate seamlessly with young children!

Regarding the people I didn’t have time to introduce this time, I’ve actually compiled some of their information before, and the links are listed below:

The universal language of children around the world (from “101 Books That Will Captivate Children”)

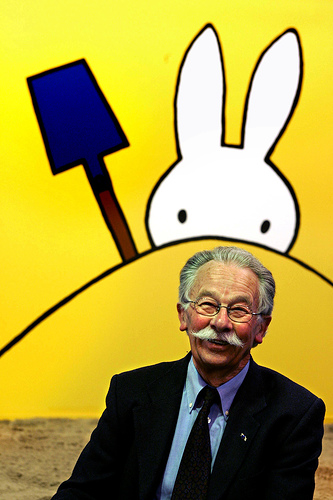

Interview with Dick Bruna, the illustrator and creator of Miffy

Miffy Picture Book Reading Guide (Picture Version)

The secret of Miffy’s success

Children’s first book: starting with Miffy

Experimentation is the twin brother of chance: from “Miffy” to “Micro Psychoanalysis”

About Janos——

Janos picture books in China

Janosz’s World

* Not long ago, while communicating with a German illustrator and picture book researcher who came to Beijing, I got to know more about Janosch and learned that he is indeed a highly respected representative figure in the German children’s literature world. In the words of that scholar: A genius like him who can write and draw by himself is very rare even in Germany.

About Yoko Sano——

Yoko Sano returned to Beijing in May 2007 to look for her former residence

[Review] Record of Yoko Sano’s 2007 Beijing Readers’ Meeting

While waiting for spring in the ancient capital, I miss a woman who is in a foreign country…

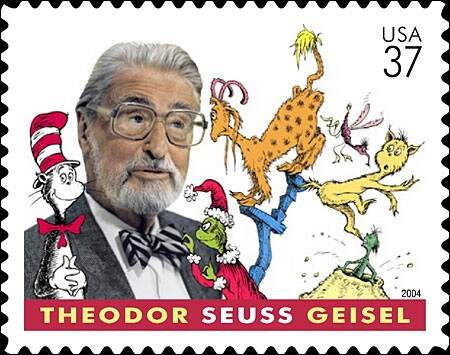

About Dr. Seuss——

[Note 16] Reading Dr. Seuss to your child before bed? Be careful!

About John Burningham——

John Burningham

[Study Session Sharing] John Burningham, Works and Related Materials

About David Wisner and Anthony Brown –

David Wisner

Anthony Brown

[Reading Session Sharing] Information about David Wisner’s “The Three Little Pigs”

[Study Session Topic] How to read stories from pictures in picture books?

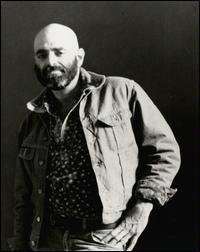

Finally, let’s talk about Silverstein——

The alternative genius uncle Shel Silverstein

Silverstein was a man who was particularly reluctant to discuss his personal life, often specifically pleading with the media to avoid mentioning it in their reports. Therefore, official information about his life is incredibly scarce. What’s even more surprising is that (I hadn’t noticed before) although his picture books and poetry collections are huge bestsellers and have truly moved many adults and children, in the pile of English picture book research monographs I’ve collected, there are very few mentions of Uncle Shel and his works. Only one children’s literature scholar briefly touched on his contribution to children’s poetry, and another psychoanalyst discussed his work “The Giving Tree” in detail. Apparently, he was bothered by the fact that the endlessly devoted apple tree in the work was referred to as “She,” a female character, and devoted considerable space to discussing issues surrounding gender relations.

But even so, there are actually many anecdotes about Uncle Schell. For example, when he was asked by his friends to create children’s books, his main job was to draw cartoons for Playboy magazine, and he had already become famous for this. It was indeed the founder of the adult magazine, Hugh Hefner, who discovered his talent and saved him from selling ice cream on the street, so the two of them were once very close.

For example, the friend who enlisted him to illustrate children’s books turned out to be Tommy Unger, another masterful picture book artist and winner of the Hans Christian Andersen Award for illustrators. His books, “The Three Robbers” and “Cricket Tower,” have been published in China. Uncle Shel recalls that Tommy practically dragged him to Harper’s. He had no faith in his ability to illustrate children’s books. But the Harper’s editor took an immediate liking to him, with an air of “If you can do it, you can do it, even if you can’t,” and he had to agree to give it a try. Thus, his first book, “A Shooting Lion,” was born, followed the following year by “The Giving Tree.”

That editor was the famous Ursula. She was determined to have Uncle Sher illustrate children’s books in 1963, the year “Where the Wild Things Are” was published. Ursula often mentioned Silverstein in her letters, always prefixing his name with “the great Sher”—a testament to her admiration for him. She described the great Sher as always so poised and radiant, as if he had just hit a winning streak at a game of jigsaw. Occasionally, she would write him personally about publishing matters, but she would also jokingly ask at the end if he’d been hanging out with the “bunny girls” in Hefner’s famous pool lately.

The dedications in each of Sher’s books have their own story, but with so few clues, most of it is guesswork. For example, “The Giving Tree” is dedicated to Nicky, his girlfriend at the time and the mother of his daughter. Unfortunately, she died young, leaving the little girl to live mostly with her aunt and uncle. “Who Wants a Cheap Rhino” is said to be dedicated to them. That girl later died of a serious illness before turning 12. The poetry collection “Light in the Attic,” published before her death, is dedicated to her—“To Shanna”—Shanna being Sher’s daughter. The name is said to be Hebrew.

By the way, I used to think Uncle Sher was black, from looking at his photos, listening to his poetry and singing. Later I learned for sure that he was white, and a true Jew. I know nothing about Sher’s parents, but I do know that he later had a son.

The Giving Tree is undoubtedly his most famous and best-selling book, but its initial response was lukewarm. The first print run of 7,000 copies took a full year to sell, and the print run only steadily increased over the first few years before it suddenly exploded in popularity. Initially, the letters the editors received were mainly from pastors who said they had just told the story in a sermon and that everyone was deeply moved…

It’s easy to feel like crying when reading the story of “The Giving Tree”, but listening to Uncle Shel singing “The Giving Tree” can make people feel particularly calm and intoxicated…

Click to play Shel Silverstein’s “The Giving Tree”

Appendix: Lyrics of “The Giving Tree”

The Giving Tree

Once there was a giving tree who loved a little boy

And everyday the boy would come to play

Swinging from her branches sleeping in her shade

Laughing all the summer hours away

And so they loved and oh the tree was happy

Oh the tree was glad

But soon the boy grew older one day he came and said

Can you give me some money, tree

To buy something I’ve found

I have no money said the tree

Just apples, twigs and leaves

But you can take my apples, boy

And sell them in the town

And so he did and oh the tree was happy

Oh the tree was glad

But soon again the boy came back and he said to the tree

I’m now a man and I must have a house that’s all my own

I can’t give you a house she said

The forest is my house

But you may cut my branches off and build yourself a home

And so he did and oh the tree was happy

Oh the tree was glad

And time went by and the boy came back with sadness in his eyes

My life has turned so cold he said I need sunny days

I’ve nothing but my trunk she said

But you may cut it down

And build yourself a boat and sail away

And so he did and oh the tree was happy

Oh the tree was glad

And after years the boy came back both of them were old

I really cannot help you if you ask for another gift

I’m nothing but an old stump now

I’m sorry boy she said

I’m sorry but I’ve nothing more to give

I do not need very much now just a quiet place to rest

The boy, who whispered with a weary smile

Well said the tree an old stump is still good for that

Come boy she said sit down

Sit down and rest a while

And so he did and oh the tree was happy

Oh the tree was glad