Miss Porter with her rabbit, Benjamin (September 1891)

The story of Miss Porter is a perfect match with Miriam Stockley’s Perfect Day :)

Miss Porter

Beatrix Potter at age 9

Beatrix Potter was born in 1866 into a typically wealthy Victorian family in London. This meant her parents relied entirely on their inheritance to lead an upper-class life, with her father spending his days in clubs and her mother constantly visiting friends and entertaining them. Fortunately, both received a good education and possessed a refined artistic background. The 2006 Hollywood film Miss Potter successfully recreated the artist’s life and upbringing.

Movie poster of “Miss Potter”

Little Beatrix Potter spent most of her time on the second floor of the mansion at 2 Bolton Park Road, where she was cared for by servants and taught by a governess. She saw her parents only at bedtime and on special holidays. Her brother Bertram, six years her junior, was her best playmate. Upstairs, they secretly kept a variety of pets, including frogs, lizards, salamanders, turtles, rabbits, and even a rattlesnake! These served as study subjects and models for the children’s paintings. However, her brother was eventually sent to boarding school, while Beatrix remained at home. The Potters likely hoped their daughter would marry into a suitable family, but even if she chose not to, they would have her manage the household once she grew up. Little did they know that Miss Potter had secretly honed her painting skills and profound knowledge of the natural sciences.

The Porter family on vacation (1882)

This was also thanks to the very wealthy Mr. and Mrs. Potter, who had a villa in the countryside of the Northern Lake District, where the whole family spent the summer enjoying the embrace of nature. There, Miss Potter found spiritual liberation and the most perfect opportunity for observation and research. She was once obsessed with the study of mosses and fungi, writing papers and painting hundreds of amazing watercolors of fungi, which were later used in many scientific monographs. If she had not been a woman, she would have beenRoyal Botanic Gardens, KewSay no, and maybe she could end up being a botanist.

Amanita muscaria

Painted by Beatrix Potter in September 1897

Courtesy of the National Trust

The talented Miss Porter could only express her literary and artistic ambitions in her secret diaries and private letters. She was keen on writing letters to the children she knew, because in the letters she could tell funny stories, draw her favorite animals, stay away from the annoying world and return to nature and innocence.

The four girls of the More family, presumably Noel’s sisters (photographed in 1900)

Anne Moore, the former governess and close friend, had eight children, all of whom were naturally devoted readers of Miss Porter’s illustrated letters, but the most devoted was Noel. Obviously, a five-year-old boy couldn’t understand the letter himself, but he could look at the pictures and ask his mother to read the story to him. Miss Porter had deliberately designed this—perhaps the greatest secret of the so-called “modern picture book”:It is best to ask children to look at the pictures while adults read the text for such stories. The pictures conveyed visually and the text conveyed auditorily are cleverly combined to form a complete story. Both children and adults can get the greatest enjoyment and pleasure in the process.

If you have the opportunity, try picking up a palm-sized copy of “The Tale of Peter Rabbit,” inviting your child to sit beside you or snuggle in your arms, and reading this century-old classic aloud to them. You’ll be captivated by the joy they bring. Even J.K. Rowling, the magical mother who created the “Harry Potter” bestseller, chose the little books written by Miss Potter a century ago when choosing a book to read aloud to her seven-year-old daughter. What a magical power that is! Miss Potter seems to have a deep understanding of the inner world of children. While her stories have a touch of didacticism typical of that era, they are generally lighthearted and playful, focusing more on appreciation and encouragement for children. Most amazingly, the animals you see in the illustrations are clearly small animals—they’re so accurate they could be straight out of an animal encyclopedia—yet they possess the demeanor, movements, and emotions of humans (primarily children), often wearing human clothing, and the more you look at them, the more adorable they become. Reading such stories, you might even unconsciously imagine yourself as a member of the animal family, sharing their joys and sorrows. The perfect combination of natural and realistic animal images with vivid fantasy is Miss Potter’s most magical feature, and no one has surpassed her in this field so far.

But even she didn’t realize it at the time. The More children, out of their love for the illustrated stories, asked their mother to keep every letter safe. Anne meticulously preserved them, encouraging Potter to adapt them into a book, and promising to lend them back to her at any time. In 1900, Potter finally decided to adapt The Tale of Peter Rabbit. Based on publishing needs and, reportedly, on the advice of Noel, the first reader, Potter significantly expanded Peter Rabbit’s adventures in the vegetable garden, more than doubling the number of images.

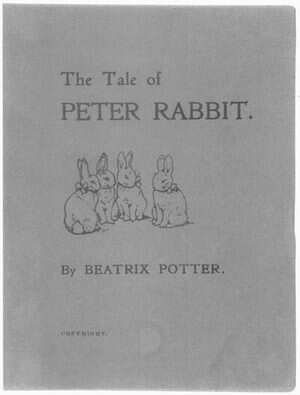

The cover of The Tale of Peter Rabbit, published by Miss Porter at her own expense in December 1901

Potter insisted that the book be palm-sized (approximately 105 x 140 mm) and in black and white, ensuring a low cost and price, making it accessible to as many children as possible. However, the publishers she submitted the book to were uninterested, likely because it was too different from popular children’s books at the time. Only one, Frederick Vaughan & Co., showed some interest, but they were still debating whether the illustrations should be in color and the text should be verse. Just before Christmas 1901, Miss Potter self-published the initial black-and-white edition, printing 250 copies to give away among friends and family while also testing the waters for sales. The book proved incredibly popular, with even Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the author of Sherlock Holmes, buying a copy for his own children and praising its format and content. A week or two later, Miss Potter printed another 200 copies. Vaughan & Co. finally decided to publish the book, but recommended a color edition.

Cover of The Tale of Peter Rabbit, published by Vaughan & Co., 1902

After the two sides finalized the text, it took nearly six months of revisions, deletions, coloring, discussions, redrawing individual panels, and finalization. Another three or four months of production, proofing, copyediting, printing, and binding finally brought the “Little Rabbit Book” to fruition. Upon its release, 8,000 copies were sold in early October 1902, with a print run of 28,000 by the end of the year. Soon after, it also achieved great success across the Atlantic in the United States. In a 1905 letter, Porter optimistically predicted, “I believe ‘Peter’ will be in print until 1907!” However, she was far too conservative. Not only did ‘Peter’ remain in print until 2010, it even made its way to China!

2002 Centennial Complete Restoration Edition

2004 officially authorized Chinese hardcover edition

A new hardcover translation will be released soon

Illustration Appreciation 1

Illustration Appreciation 2

Illustration Appreciation 3

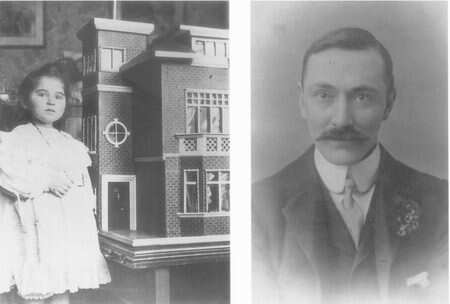

Over the next three years, Porter collaborated with Vaughan and Company to publish “The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin,” “The Tailor of Gloucester,” “The Tale of Little Benjamin Rabbit,” and “The Tale of Two Bad Mice.” Both publication and sales were successful, and her creative drive was intensified, with one brilliant idea after another. During this period, she developed a close friendship with her publisher, Mr. Norman (Frederic Vaughan’s youngest son), who offered her unwavering support and support. Norman, finding himself deeply in love with this strong-willed and passionate woman, wrote to propose marriage. Porter was overjoyed but also deeply concerned. As expected, her parents strongly opposed the idea, believing it was a disgrace to marry into such a merchant family. Porter, already 39 years old and still financially independent, was forced to vigorously fight her parents’ case. Ultimately, they reached a compromise: a secret engagement followed by a year’s wait to see what would happen. This decision was already painful enough, but Norman suddenly died of pernicious anemia a month later at the age of 37. At that time, Miss Porter was spending the summer with her parents in the Lake District. She didn’t even see her fiancé for the last time, and the world didn’t know about their relationship.

Mr. Norman and Miss Porter in the film

On the right is a photo of Mr. Norman and on the left is the dollhouse he found for Miss Potter.

This dollhouse was the setting for “A Tale of Two Bad Mice”

After this major blow, Potter became stronger. She continued to create picture books and maintained her cooperation with Vaughan Company. In the nearly 30 years, she created a total of 23 picture books, all of which have been reprinted to this day. Unexpectedly, she found that she had become very wealthy, so she bought herself a farm in the Lake District village of Thorley, which made her fall in love with it. Gradually, she began to break away from her parents’ control, away from the sad place of London, and lived alone in the countryside, painting, sketching and creating.

Beatrix Potter at Hilltop House (1913)

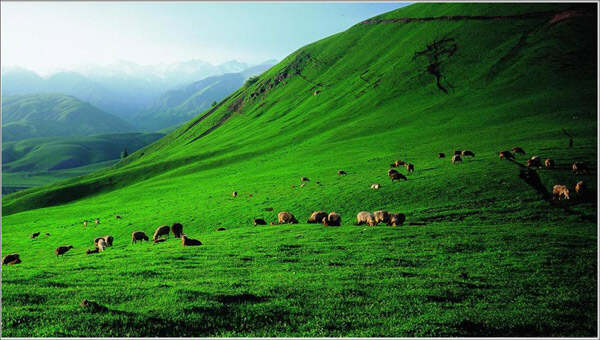

She loved the beauty of the Lake District so much that, to others, she seemed almost madly infatuated. Her books sold increasingly well, and she became increasingly wealthy. She began frequenting Lake District land auctions, always bidding slightly higher than others to secure this farm, that pasture, here and there, leaving other property owners baffled. Only local lawyer William Harris understood Miss Porter’s intentions. They worked together happily, and finally married in 1913, when Porter was 47. They remained together for thirty years.

Beatrix and William pictured the day before their wedding

From October 15, 1913 she became Mrs. Harris

In her later years, she became increasingly passionate about hands-on farming, herding Herdwick sheep and encouraging the breeding of this endangered goat species on all her farms. Her goats consistently swept the major local goat competitions. She was later deservedly elected President of the British Herdwick Sheep Society. After 1930, she completely abandoned her creative activities to devote herself entirely to her farm, living a simple life typical of a local farmer, working the land herself.

Beatrix in her later years

When Beatrix Potter died in 1943, she owned 4,000 acres (16 million square meters) of land in the Lake District, 15 manors and farmhouses, and numerous scenic spots, including the glacial lake of Howth. In her will, she donated all of this to the National Trust, a religious charity dedicated to protecting the natural environment. Under British law, religious charities’ land cannot be auctioned! Thanks to her tireless efforts in the latter half of her life, no real estate developer has had a chance to target the Lake District. The Lake District’s ecology has been preserved intact, with hares still roaming the hills and Herdwick sheep still grazing leisurely. All this is thanks to the magical Peter Rabbit and his many friends.

Before her death, Miss Porter entrusted a shepherd she trusted to scatter her ashes on a hill in the village of Soli and to keep it a secret. Now, the shepherd who kept his promise has long passed away…

One of the current lake district landscapes

Today’s Lake District Scenery 2

For more information about Miss Porter, please visitThe World of Beatrix Potter”.

To know what happens next, please wait for the next episode.

Masters of the Art of Storytelling for Children (Part 4)