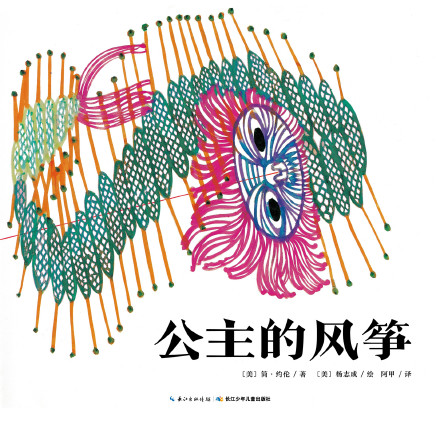

The Princess’ Kite is the second picture book written by Jane Yolen that I have translated. The first isGoodbye, Happy Valley (illustration by Barbara Cooney)In that story, she recounts in the first person how her hometown, the Happy River Valley, was flooded by the construction of the Cobbin Reservoir. The story moved many, leading many to believe it was a genuine account of her childhood, when she lived in the Happy River Valley in Massachusetts. In fact, she was a true New Yorker, born and raised in the city. She moved to the vicinity of the reservoir with her husband after marrying and having children, and later wrote the story. Her storytelling skills are truly admirable.

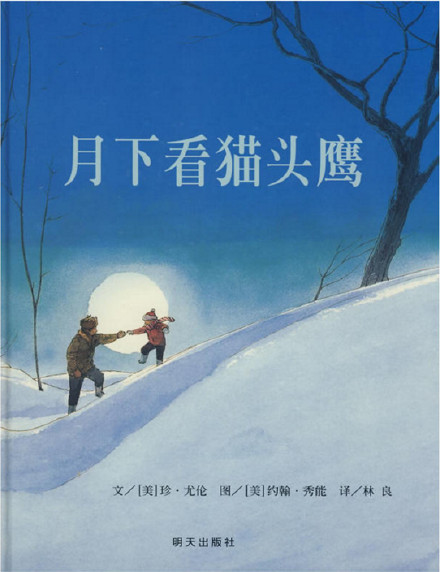

Most Chinese readers were introduced to Jane Yolen through her picture book “Watching Owls Under the Moon,” which won the 1988 Caldecott Medal. Of course, the award went to illustrator John Shonen, but it’s hard to imagine the success of her work without Jane Yolen’s beautiful, quiet story. She is a prolific writer, not only of picture books but also of poetry, fairy tales, novels, and nonfiction for both children and adults. She has won numerous awards, the most prestigious of which are two Nebula Awards and a World Fantasy Award, two of the highest honors in science fiction and fantasy literature. Over the years, she has created at least 150 high-quality original fairy tales, beloved by readers. Some critics have even hailed her as the “American Hans Christian Andersen.” However, she is somewhat uncomfortable with this praise, explaining that she simply enjoys turning her life experiences and feelings into stories. For her, writing is not just work; it’s also entertainment, or, in other words, life itself.

Even a quaint Chinese folk tale like “The Princess’ Kite” is based on her life and, in her own words, is a semi-autobiographical story. The emperor in the book is Yolen’s father, and the little princess is of course herself. She says she always wanted to do things to please her father, but she never found the right way.

Jane Yolen as a child with her parents

Her father, Will Yolen, was a multitalented genius. He worked as a journalist and screenwriter, but his greatest passion was kite flying. His devotion reached such a high level that he won the World Kite Championship and set a Guinness World Record for continuous kite flying for 179 hours. He was one of the key figures in promoting kite flying as a popular sport in the United States in the 1950s. His daughter rightly called him the “Kite King” in her dedication. Legend has it that Will, so engrossed in his kite flying, accidentally fell into Long Island Sound, and it was his daughter who managed to rescue him from the sea. A bit like a little princess saving her father, isn’t it?

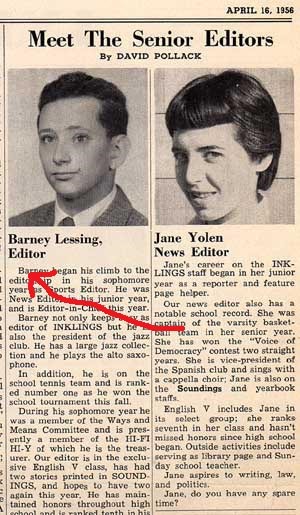

Jane Yolen worked as a newspaper editor as a teenager, and it almost became her career.

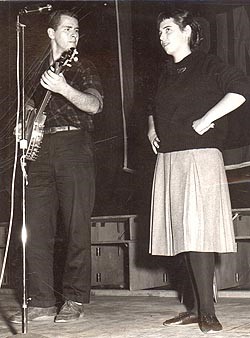

Jane Yolen of Girls’ Generation can sing and dance

I gave up ballet just because of my body shape.

Jane Yolen’s inspiration for this story stems from her father. It began in 1961, a year after graduating from university at the age of 22, when she was looking to become a freelance writer. Her father had asked her to write a book about kite flying, and he asked her to be the “author.” Despite the modest royalties and the fact that her name couldn’t be on the book, she happily accepted. While researching every available source on kites, she came across a book that mentioned how Emperor Shen, imprisoned in a tower, was saved by a kite. This inspired her, leaving a vivid image that stuck with her, and she wrote the story years later.

It was a shame that the talented editor, Susan Hirschman, initially rejected the story as unsuitable for children!

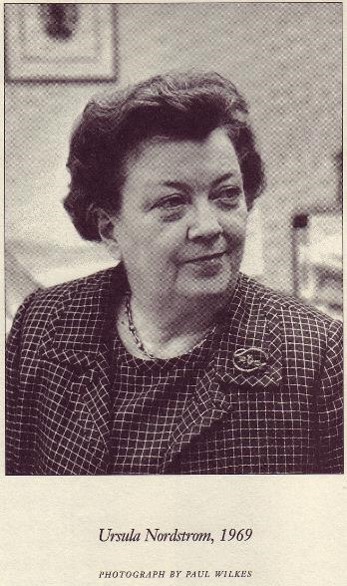

However, the book’s publication was somewhat fraught. Around the mid-1960s, Jane Yolen’s primary collaborator left Macmillan. Susan Hirschman, who subsequently took over the department, disapproved of the story. She frankly told Yolen that she wasn’t very good at writing children’s stories yet, and perhaps she would gain some insight after having her own children. Susan, a top editor, had been the right-hand woman of legendary Harper’s editor Ursula, and it was she who discovered Pat Haggins in 1967 and mentored her in the classic Hen Rose Goes for a Walk. Even the best editors can make mistakes. Fortunately, Jane was a confident writer, and she asked her agent to continue submitting her work to other publishers. Finally, in 1966, she found a kindred spirit. Ann Beneduzzi, editor at World Publishing, not only decided to publish the book but also hired Chinese-American artist Yang Zhicheng to illustrate it—a truly remarkable combination!

It turns out that Yang Zhicheng’s debut in the American children’s book industry is related to Ursula Nordstrom!

The story of Yang Zhicheng and Ursula is also written in “The Power of Childhood”

The story of Yang Zhicheng and Ursula is also written in “The Power of Childhood”

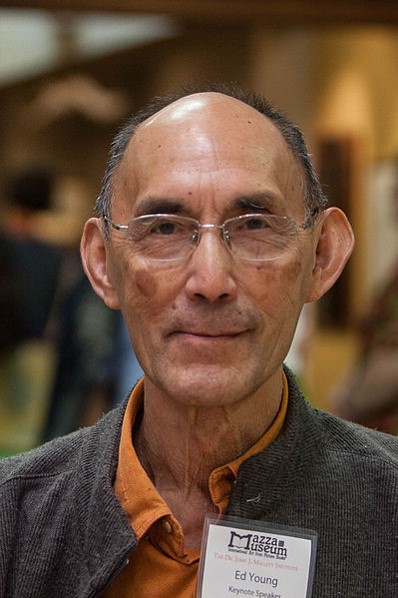

Coincidentally, Yang Zhicheng’s debut in the American children’s book industry coincided closely with Jane Yolen’s. Initially working as an advertising designer in New York, he enjoyed sketching animals in Central Park in his spare time. A friend recommended him to Ursula of Harper’s. Ursula was so impressed with Yang Zhicheng that she immediately commissioned him to illustrate The Nasty Mouse and Other Nasty Stories by Woodley (author of “Trees Are Good”), published in 1962. Although Yang Zhicheng himself disliked the book and never collaborated with Ursula again, it won the Graphic Design Association’s Award for Excellence that year. Publishers flocked to him, and Yang Zhicheng was drawn into the children’s book world, a position he would later deepen.

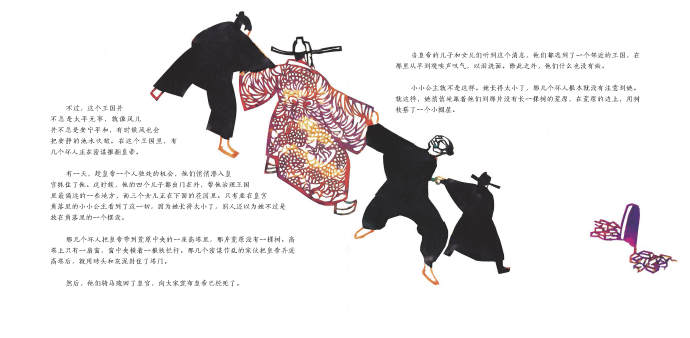

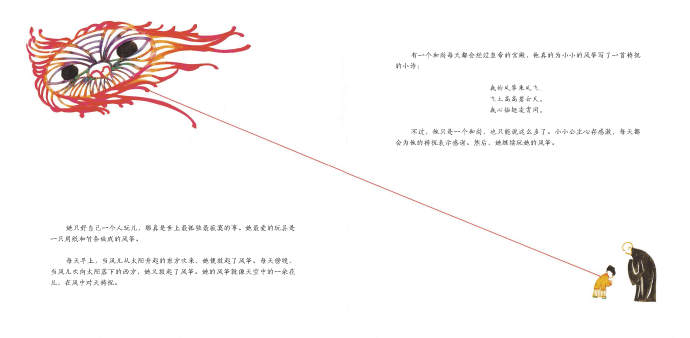

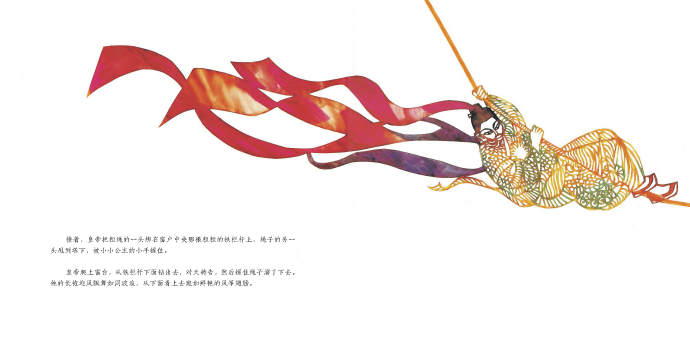

Illustrations for The Princess’ Kite, whose bold white space is still stunning today!

The artist imbues this story with a rich Chinese flavor. Not only does he accurately depict the author’s intended narrative, but his images reveal something more, perhaps even unimagined. The most striking aspect is his use of paper-cutting as his primary creative medium, a groundbreaking experiment in the Western picture book world at the time. Even more striking is his generous use of white space in the composition. This not only contrasts with the vibrant paper-cut illustrations but also allows for a vibrant “qi” (energy) to flow through the canvas. The attentive reader can sense the flow of this energy, hinting at the artist’s exploration of the qualities of wind. This creative approach embodies the spirit of traditional Chinese literati painting, offering a fascinating glimpse into Zen philosophy. Around 1965, Yang Zhicheng began studying under Zheng Manqing, a master of poetry, calligraphy, painting, martial arts, and medicine, and presumably gradually gained insights.

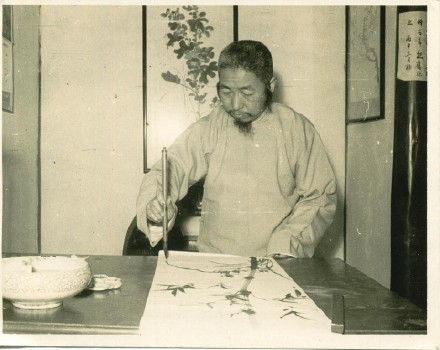

Yang Zhicheng first met the retired Wujue old man in the United States to treat his leg disease, but because of this opportunity, he became his disciple!

The Princess’s Kite won the Caldecott Medal in 1968, the first truly prestigious award for both the artist and the writer, giving them a significant boost in their creative careers. The book also won the Lewis Carroll Bookshelf Prize, a truly remarkable award, meaning it “deserves to be placed on the same shelf as Alice in Wonderland”! This truly deserved honor is truly remarkable. This legendary story of love and loyalty, illustrated with vibrant and beautiful Chinese illustrations, is a true addition to any bookshelf.

Ajia …

Written in Beijing on March 5, 2016(Revised on January 2, 2017)

[Translation Highlights 1: Dedication]

The dedication of the author and painter of The Princess’ Kite is very interesting. The author Jane Yolen wrote: “For my father,

who is the king of the kite fliers, and for my little princess,

Heidi

Elisabet.” — Dedicated to her father, the reason has been mentioned above; but why is it dedicated to her “Little Princess Heidi”? It is a family anecdote: in 1962, Jane Yolen married David Stamp (who later became a famous computer scientist).

The couple’s first few years were filled with romance. In 1965, they decided to take a break from regular work and embark on a year-long European tour, one taking photos with a camera, the other writing on a typewriter. They traveled for about eight months and, when they arrived in Rome, discovered they were expecting their daughter, Heidi.

Jane Yolen and David Stamp’s happy family, Heidi has two younger brothers

Heidi was born in 1966. During the period of her pregnancy, Jane Yolen sold the copyright of “The Princess’s Kite”.

“Little Princess” is her lucky star!

When Heidi grew up, she first worked in other professions, and later turned to writing children’s books, mainly collaborating with her mother.

The original dedication by illustrator Yang Zhicheng reads: To my mother, “Rivaling the

Clouds,” for her gift of boundless energy and artistic

resourcefulness, and to the friendly rivalry of ACS where it

This is dedicated to his mother. I know his mother’s Chinese name is Tang Yun, but “Rivaling the

“Clouds” may be a character or an alias, it’s hard to guess (I initially guessed it might be “Lingyun”

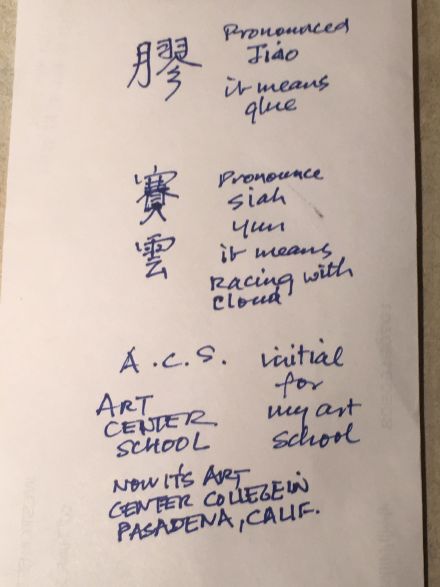

ACS, I found out, is likely the former abbreviation of his alma mater, Art Center College of Design (now renamed), but I’m not entirely sure. So, regarding the translation of this dedication, I had to ask Yang Zhiben himself. He kindly replied, and the original image is below:

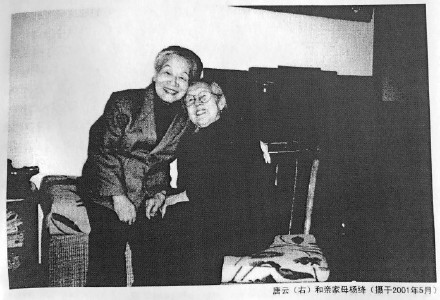

This is the origin of the Chinese translation of the dedication, “Saiyun.” I suspect this very Chinese story reminded Yang Zhicheng of his mother, whose energy and artistic inspiration seemed boundless, and the image of the kite also has some connection to “Saiyun.” (Also, Yang Zhicheng’s mother was born in the Year of the Dragon; could this also be related to the image of the kite?) Out of curiosity, I found a biography of Yang Zhicheng’s father, “Yang Kuanlin: China’s First Generation Master of Architectural Structural Engineering Design,” which includes a photo of his mother:

This is a photo of her and her mother-in-law Yang Jiang! It turns out that Yang Zhicheng’s eldest brother is the son-in-law of Qian Zhongshu’s family——

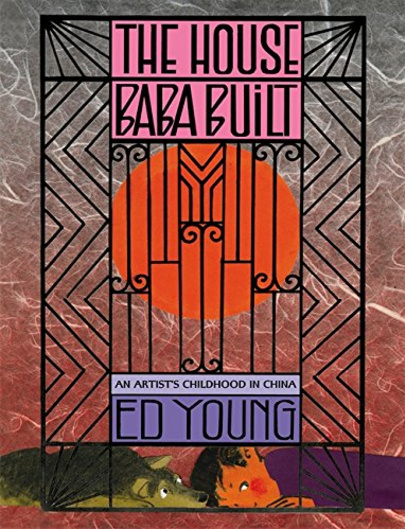

Mr. Yang Kuanlin tragically passed away in 1971, during that unique era. However, I once had the privilege of having lunch with Mr. Yang Zhicheng, and he spoke of his father with fond memories. He told me a story about how his father built a unique house for his family in Shanghai in the 1930s. It sounded like a legend. This story is now available in English, and I’ve read it myself. He was truly an extraordinary father!

Yang Zhicheng’s childhood story “The House My Father Built”

[Translation Extra 2: Princess’ Name and Food Names]

The English name of the protagonist of “The Princess’ Kite” is: Djeow

Seow, according to pronunciation, is similar to “petite”, but the story explains that the meaning of this name is “smallest”, so “petite” is definitely not appropriate as a name.

However, on the first page of the main story, there is a character for “膠”. This is of course the “胶” in “glue”, but it may also be used as a surname in Chinese.Djeow

Could Seow possibly be “膠小” (膠小) or “膠小小” (膠小小)? We also contacted the author and illustrator through the copyright agency regarding this question. As shown in the image above, Yang Zhicheng confidently stated that the “膠” he used here simply means glue. The copyright holder, Jane Yolen, responded on behalf of the author:

As for

“Djeow Seow”: I believe this is intended to be a Chinese name that

translates as “the smallest one,” but rather than writing it in

Chinese characters (which Americans wouldn’t know how to

pronounce), they spelled it out as best as they could using English

letters. Do I explain myself clearly? I honestly don’t think the

author would know the correct Chinese characters to use, but maybe

the publisher can come up with something based on the meaning and

sounds of the name.

In short, similar to my initial speculation, Jane Yolen likely didn’t design this English name based on any Chinese characters she knew. Instead, it was derived from a hypothetical or perhaps an unheard-of pronunciation. Even the illustrator, who knew Chinese at the time, couldn’t figure out which character it was. So, we had to create a name based on the original meaning, and that’s how “Little Princess” came to be.

In the story, the little princess’s daily food delivery to her father trapped in the tower is also very interesting. There is a poppyseed in the original text.

Cakes, what is this? See the picture below:

It turned out to be a poppy seed cake! In such a distant ancient time, how could a little princess send such a Western-style cake to her father in the tower every day? Perhaps Jane Yolen was thinking about the “Opium War”? Anyway, foreigners’ associations with Chinese food are actually quite suspicious. However, poppy seeds are used in Chinese food, generally used to make cooking oil, called “imperial rice oil”. Poppy seeds are also called “imperial rice”, and the word “imperial” has a royal connotation. So poppyseed

In this book, cake is translated as “御米冰” (note that it is not “御米冰”).

(As for what “imperial rice cakes” taste like? I haven’t tried them either. Next time, I’ll try to adapt the poppy seed cake recipe and make them into pancakes. Perhaps they’ll taste good too!) (*Note: Regarding the Chinese food in this book, a young reader went to the US to ask Jane Yolen in person how she came up with it. The American author frankly said she had no idea; it was illustrator Yang Zhicheng’s idea!)

Just a secret, the “water chestnut” in the original text was originally “water caltrop”. I also changed the recipe and I feel that water chestnut is more suitable for the emperor on the tower to fill his stomach ^_^