Once upon a time, there was a boy named Johnny who was nearly starving to death. An old woman gave him a seed (said to be a fairy). Johnny planted the seed and carefully tended it for a month (somehow he managed to survive), until a delicate pink flower grew. He then devoured it with such eagerness! Although the flower didn’t fill him up, it enabled him to understand the speech of animals, and he went to where the animals gathered and became their friends.

Two flowers bloom, each with its own beauty. In that kingdom, there lived a prince named Margarine, a tyrannical and greedy man (in short, not a good person). One day, however, the prince disappeared. The king posted a notice offering a reward for finding the Margarine Prince. Whoever found him would receive a large sum of money, a princess, and the chance to live in the palace forever. However, the prince was imprisoned in a cave, guarded by two giant dragons that never slept…

Then what?

Will Johnny save the Margarine Prince? How?

If the rescue is successful, will Johnny get a reward and a princess, and live in the palace forever?

If you’re a teacher or parent who wants to inspire children to write, share this story with them and ask them to continue telling and writing about it. You could also explain that the story originally ended here, and no one knows what happened next. The author of this story is none other than the world-renowned storyteller, Mark Twain!

Did Mark Twain really write such a “childish” fairy tale? Absolutely. He was not only a great writer, but also a father of several children. Writing and telling stories to his children is a father’s unshirkable responsibility (and, of course, the highest honor). While we mere mortals usually rely on reading books, Mark Twain, as a great writer, naturally drew on his own repertoire. According to his own diary, his daughters would often “force” him to tell stories, simply pointing to an illustration in an adult magazine and asking him to start a story based on it. He always happily complied, telling stories until his children were satisfied.

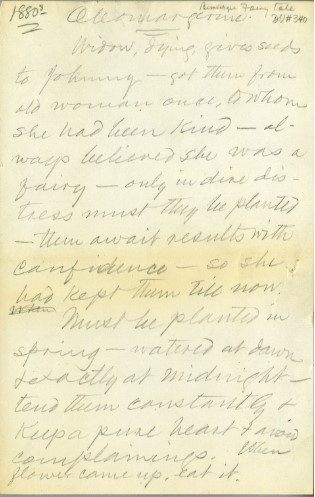

Many wonderful things must have happened in these heartwarming family storytelling sessions, countless magical ideas coalescing and dissipating like smoke. Unfortunately, there were no recorders back then, and the great writer himself didn’t bother to record them. Fortunately, there was one exception. Over several evenings in April 1879, they shared the story of Johnny and the Margarine Prince. Although it was a tale improvised from a human anatomy diagram, his two daughters (7‑year-old Susie and 5‑year-old Clara) clamored to continue, a great encouragement to the storyteller. Driven by some impulse or revelation (perhaps he decided the story had publication value), he finally wrote down the main points of the story in his notebook. Unfortunately, he didn’t write down the conclusion. Perhaps they hadn’t finished telling it, or perhaps he wasn’t satisfied with the live ending—in short, he left it as a mystery.

The unearthing of this long-lost mystery was by Dr. John Bird, a Mark Twain scholar. “Mark Twain actually attempted to write a fairy tale”—it was indeed an exciting discovery. But who could resist the question of “what happened next?” after seeing the 16 pages of handwritten notes? Bird added to and continued the story, completing it. Critics who have read Bird’s version of the story describe it as a faithful reproduction of Mark Twain’s style, told as if speaking to the two young daughters, informed by their knowledge of the family. Unfortunately, this version is currently unavailable; all we know (according to reviewers’ spoilers) is that Johnny successfully rescues the prince, receives the reward, and marries the princess—a perfect fairy tale ending.

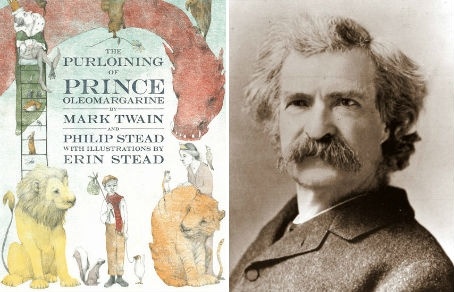

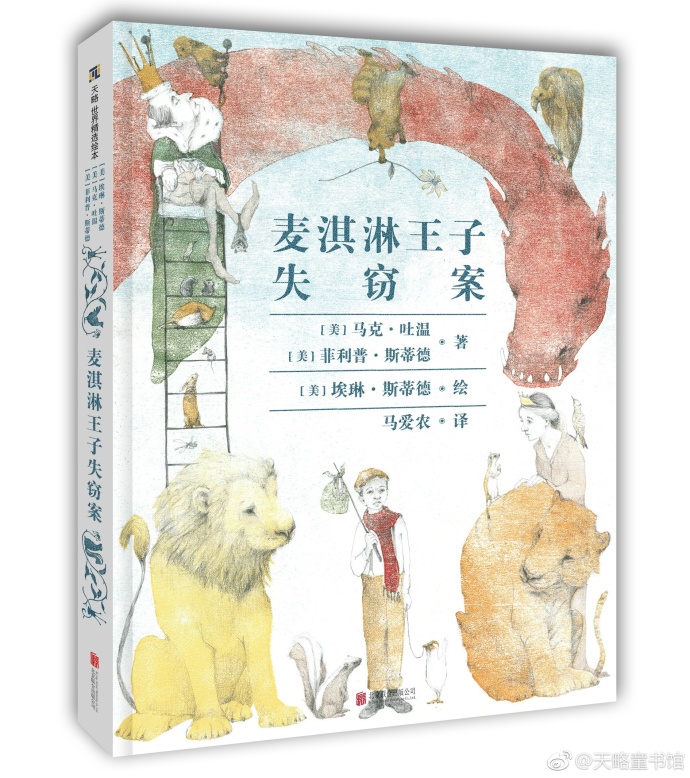

However, when Bird submitted his version to a publisher seeking publication, they rejected it. Instead, they turned to a young children’s book duo, the Steeds. Philip and Erin Steed’s collaboration, “Amo’s Sick Day,” had won the Caldecott Medal. Their subsequent collaborations, “Big Bear Has a Story to Tell” and “Lennie and Lucy,” were also highly popular, garnering countless fans. All of these books are available in Chinese, which I happened to translate. I met with the Steeds face-to-face. They are indeed young, but they possess a rare ability to be quiet and focused, and possess a remarkable creative energy. How could they resist the allure of collaborating across time with a great writer who had passed away over a century ago to complete this story? They toiled tirelessly for three years, endlessly researching, refining, and experimenting. To complete the manuscript, Philip spent ten days alone on a secluded beaver island, so much so that the island itself became part of the story.

What we have here is the Steeds’ version of “Mark Twain’s Fairy Tales.” This may sound strange, but is the story the Steeds’ or Mark Twain’s? The answer is both—as evidenced by the joint signature on the cover.

In reality, when an original story is retold, it largely becomes someone else’s story. Even translation from one language to another is, to some extent, a rewriting or re-creation, and thus becomes the translator’s story. Therefore, a more extreme view is that translation is tantamount to “murdering” the original work. Rewriting and continuing the story are obviously more suspicious of “murder” than translation. It is said that carefully added illustrations are also suspected of similar crimes, as they all take the story in directions that the original author may not have even considered. Therefore, when reading the Chinese version of this story, you must be mentally prepared. The fairy tale of the legendary Mark Twain may have been “murdered” three times, by the Steeds and Ma Ainong! But from another perspective, if there were no such “murder”, how could there be rebirth?

The current version of the story of “The Theft of the Prince of Margarita” has two very typical (and perhaps seemingly conflicting) sides:

On the one hand, the book might seem a bit old-fashioned today, with long sentences and profound language. The main plot is often filled with innuendo, mocking social injustice and the fragility of human nature, albeit veiled in humor. Perhaps this approach is very “Mark Twain-esque,” at least based on Steed’s understanding of him. To make it more natural, Philippe doesn’t hesitate to dive into the story, dragging Mark Twain into the mix, debating everything from worldview to plot direction and character fates (for example, whether the old woman actually dies). This postmodern narrative approach compensates for the book’s often jumpy plot lines. However, this approach also significantly increases the book’s difficulty level, and even a seven-year-old might need an adult to read aloud and provide appropriate explanations.

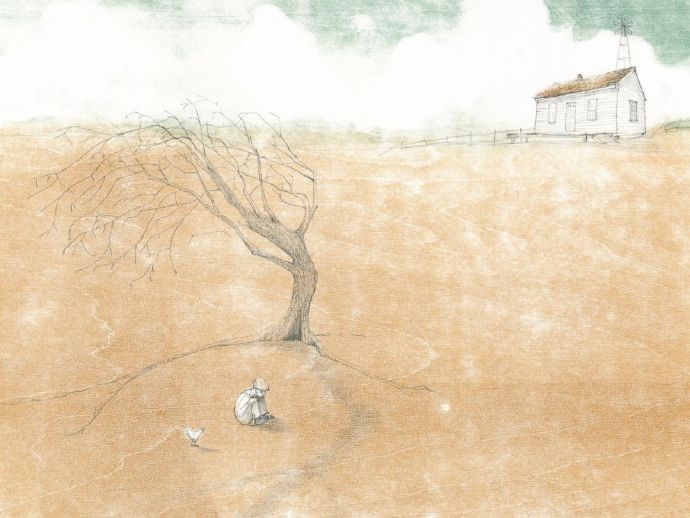

On the other hand, this story is surprisingly heartwarming. The margarine prince barely serves as a figurehead; the boy Johnny is the undisputed protagonist. He’s so kind, calm, and unwavering that the animals and the cave dwellers (perhaps all representatives of overlooked groups) instantly become his friends, and even the queen treats him with such tenderness. Yet Johnny doesn’t seem to do anything special, nor does he possess any unique abilities. He simply humbly and genuinely expresses his joy in connecting with others—a simple yet heartwarming emotion that seems to melt everything. This is clearly not “Mark Twain-esque,” but rather a hallmark of “Stee-esque.” In their collaborative stories, the relentless theme is “friendship,” a value far greater than money, princesses, or the perks of living in a palace.

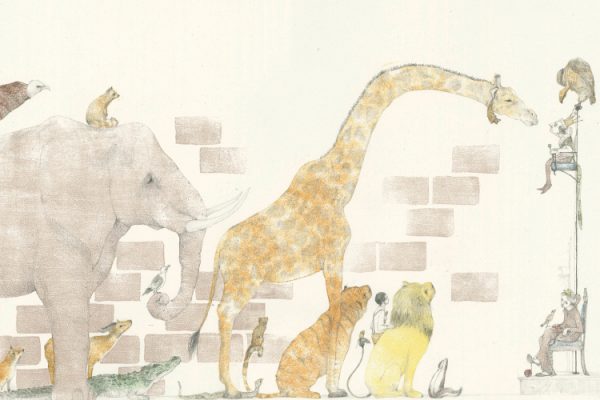

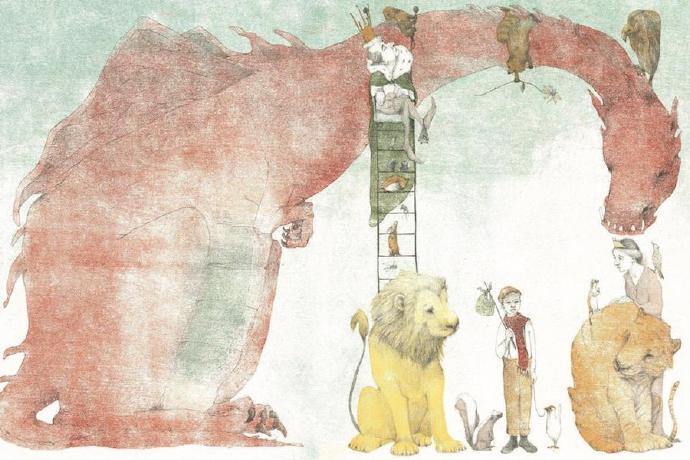

Erin’s illustrations elevate the story’s simplicity, tranquility, and warmth to a tee. The book’s illustration style is very similar to “Almo’s Sick Day” and “Lennie and Lucy,” likely primarily using woodcuts. The overall feel is subtle, ethereal, and quite nostalgic. Philip and Erin envisioned this book as being created for Mark Twain’s daughter. The title page features a quote from Susie, who recalled her 12-year-old wish in her father’s biography: “I’ve always wanted Dad to write a book, a book that would reveal his compassionate nature.” The humorous yet incisive Mark Twain never wrote such a book, but Philip and Erin helped him accomplish it.

Perhaps particularly devoted Mark Twain fans may not accept this “murder,” but I think even if he were reborn, he would agree that there are many possible versions of a story, and even his own sequel is just one of them. In terms of childlike fun and warm style, he may not be able to surpass the Steeds’ version.

Ajia …

Written in Beijing on October 31, 2017