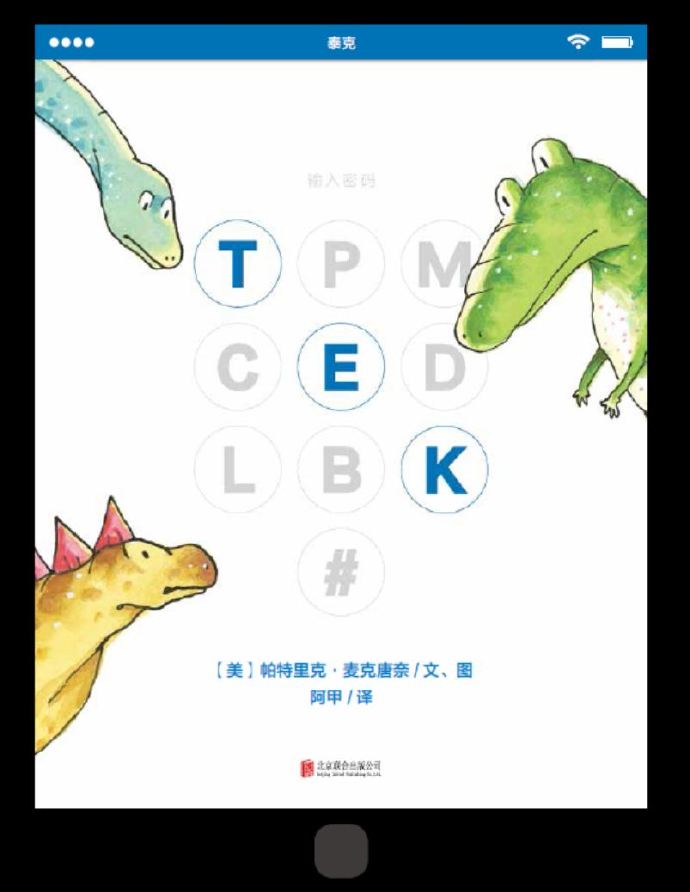

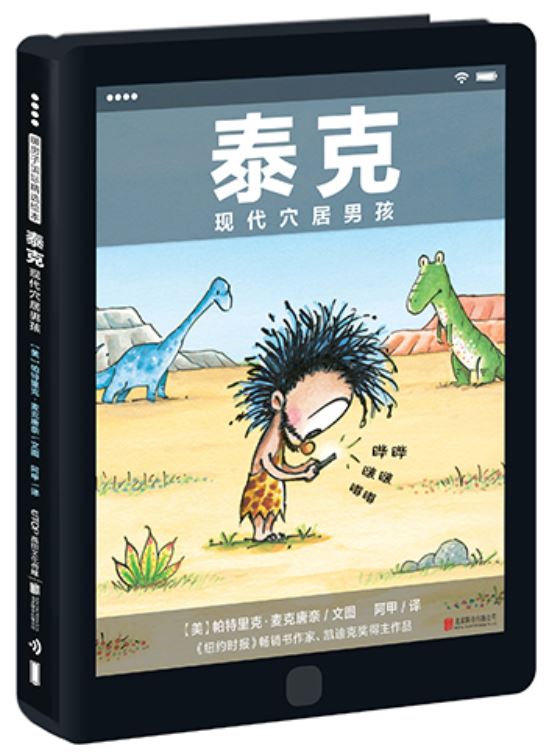

The first moment I held “Tek: A Modern Caveman” in my hands, I felt a strange sense of time travel. There were dinosaurs and a caveman child in the picture, but—why did that child look like he was looking down at his phone?! And the funniest thing is, the cover doesn’t look like a book, but more like a tablet. From a distance, it really is an iPad. And notice the top right corner of the “screen”: there are even network signal and battery indicators! The illustrator was incredibly thoughtful, even going so far as to create a realistic-looking home button right below the cover. I couldn’t help but press it while flipping through the pages, and I imagine little ones would be even more tempted.

Reading “Tek” isn’t as engaging just by looking at the images; you have to hold the thick paperback, with its cardboard cover. Just how thick is it? If you have an iPad, you can measure it—it’s roughly the thickness of the iPad plus the cover. Just how big is this book? Let’s measure it again. Hmm, it’s just the right size—the same size as an iPad! So, cartoonist and children’s book illustrator Patrick McDonnell created a book that’s a near-perfect replica of the iPad. That’s a problem, and adults might be wondering: We’re already struggling to get our kids to use screens less. Why did the creators create a book that’s a near-perfect imitation of the iPad?

This is the extraordinary quality of the cartoonist and storyteller. He clearly intended to offer advice, but first he completely “appealed to the child’s taste.” Children born today seem irrevocably digitized. They easily become fascinated by all things high-tech, using them as if they were experts in a past life. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing, but it’s certainly not necessarily a good thing either. There’s only a fine line between good and bad. Children are naturally curious. Spending time outdoors easily makes friends with animals, and they often enjoy playing in the mud and sand, which adults consider “dirty.” We now know that these activities are crucial to a child’s development and even to their lifelong happiness. But when they are trapped indoors for various reasons, and locked in front of various electronic devices voluntarily or involuntarily, they seem to be firmly stuck to them, and their curiosity about the real world and the natural world is worn away bit by bit, until it seems incurable… McDonnell created this high-imitation IPAD book, and in a fictional story that seems to have spanned tens of millions of years, he stuffed in elements that children of this era particularly like — IPAD, mobile phones, technological gadgets, games, dinosaurs, and crazy primitives, solemnly recreating a hilarious “disaster”, and actually showing different possible choices. The final right of choice is still returned to the young readers.

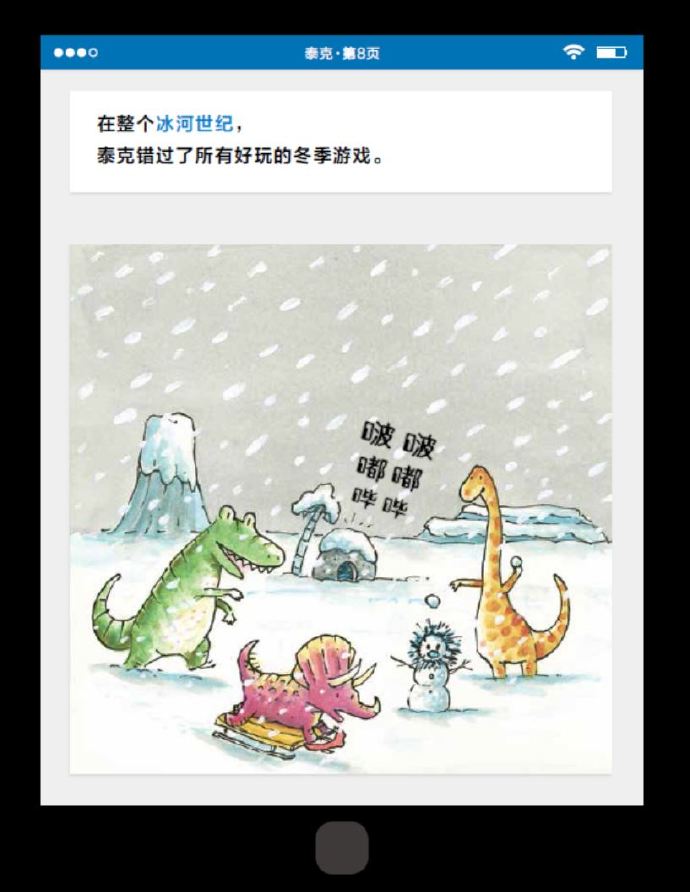

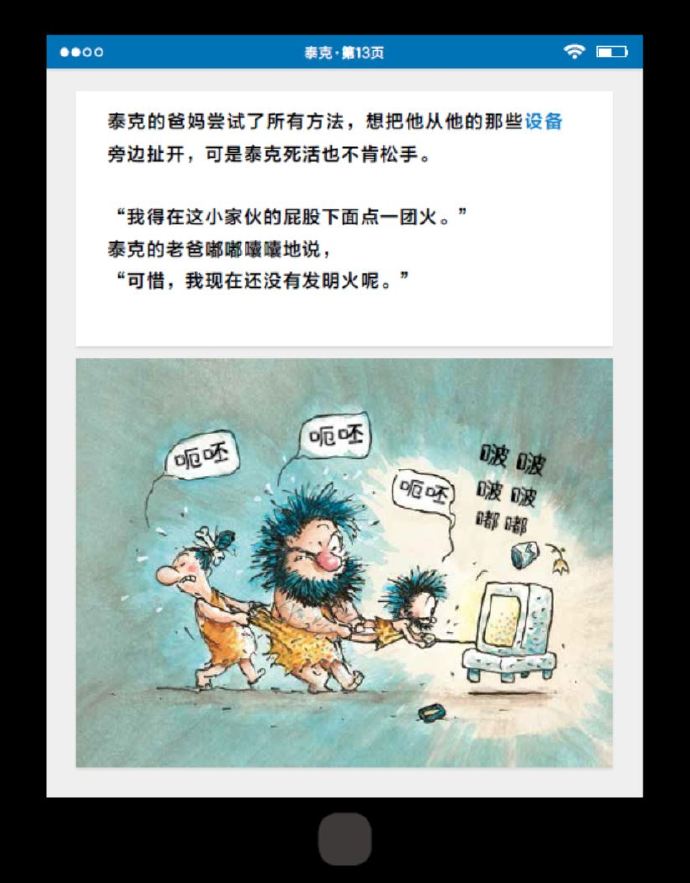

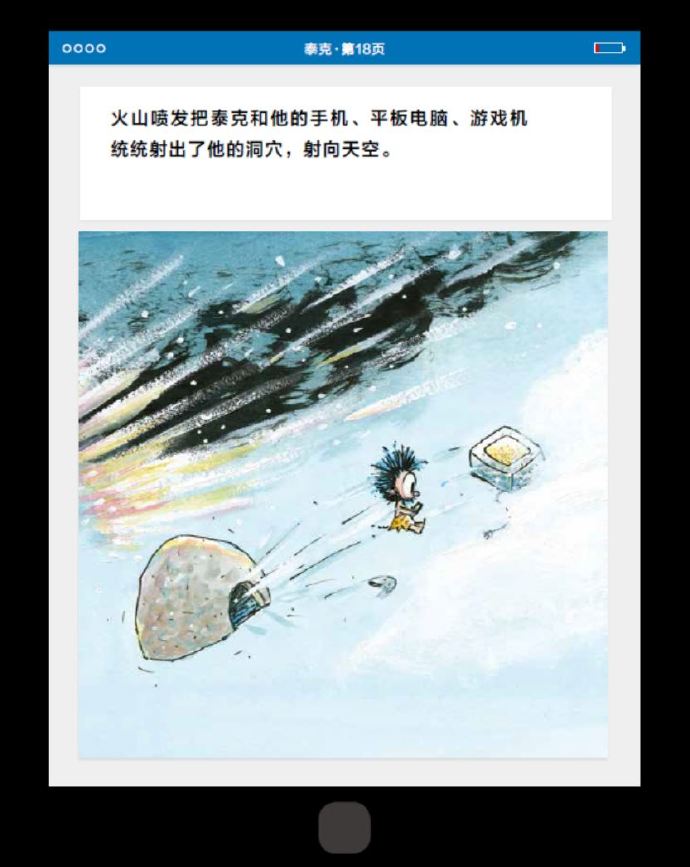

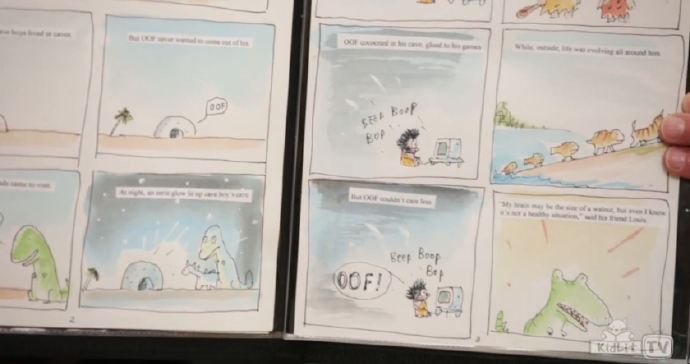

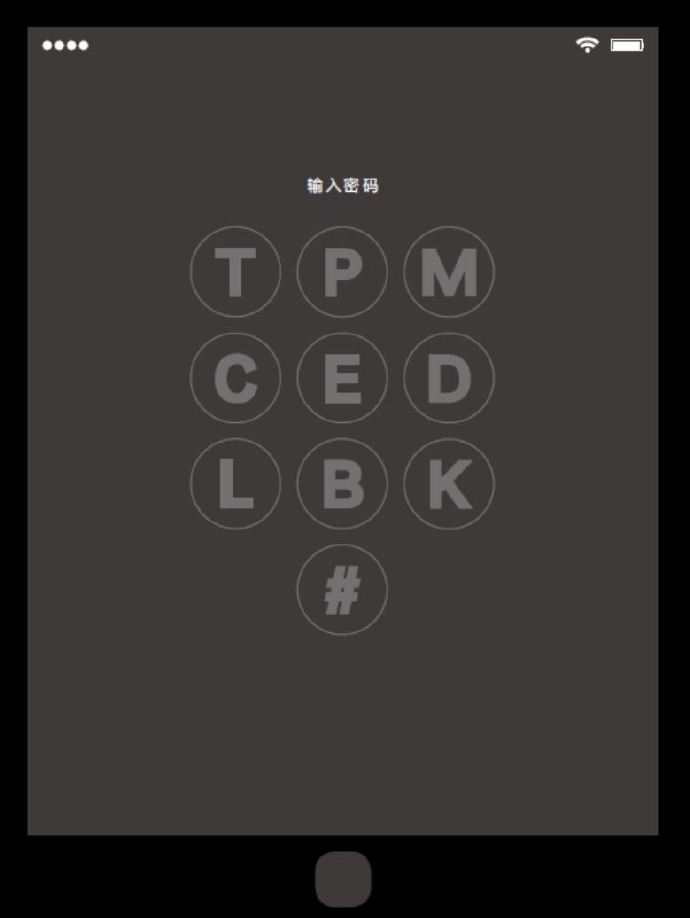

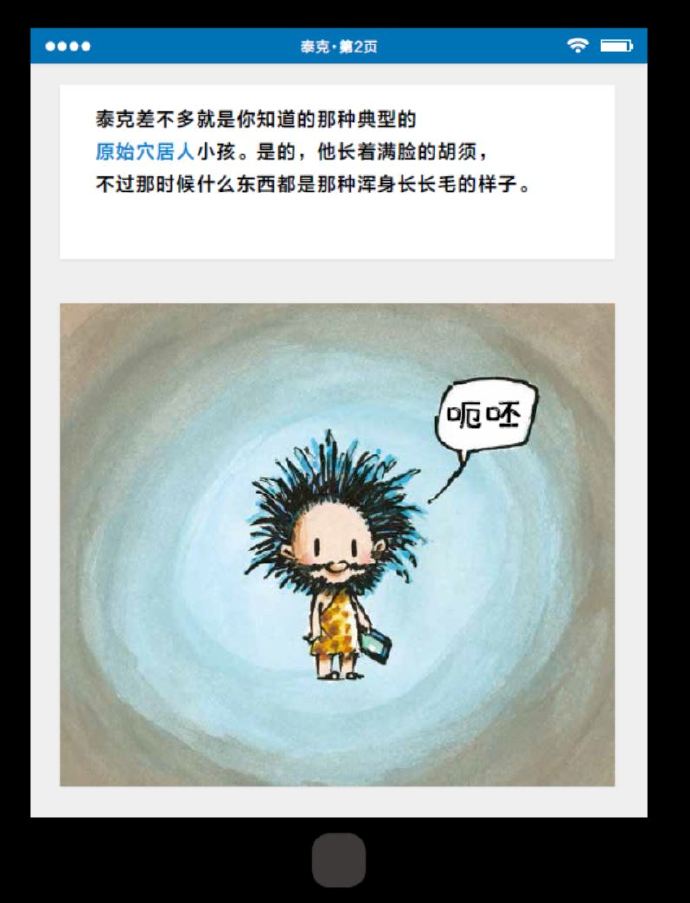

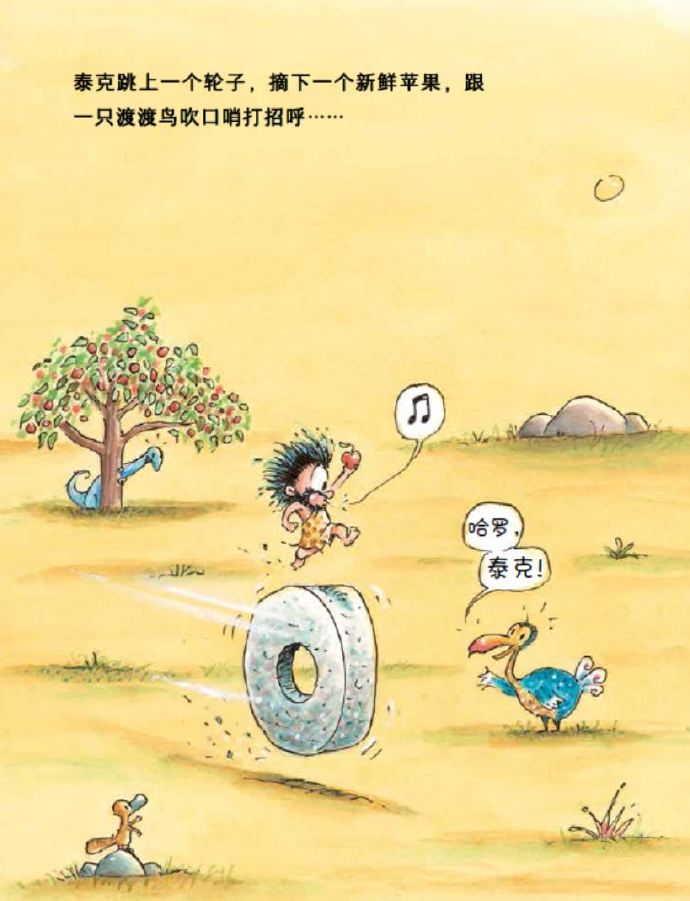

This book is broadly told in two modes. The first half can be described as “iPad-style,” requiring a password to enter. It then unfolds the story of a caveman boy named Tyke, seemingly revealed through a swipe of an iPad screen. This story has its own numbered pages, interspersed with emojis as the plot progresses. As the pages turn, the battery level indicator in the upper right corner changes color, eventually turning red and then disappearing into a black screen. After a volcanic eruption, a black screen, and a disconnected connection, Tyke escapes the iPad book and enters the conventional “picture book” world of the second half. Upon returning to this world, Tyke becomes a living person again (albeit a little savage), curious about everything around him, full of love and enthusiasm for his parents and friends, and his vibrant energy rekindled through the games he plays.

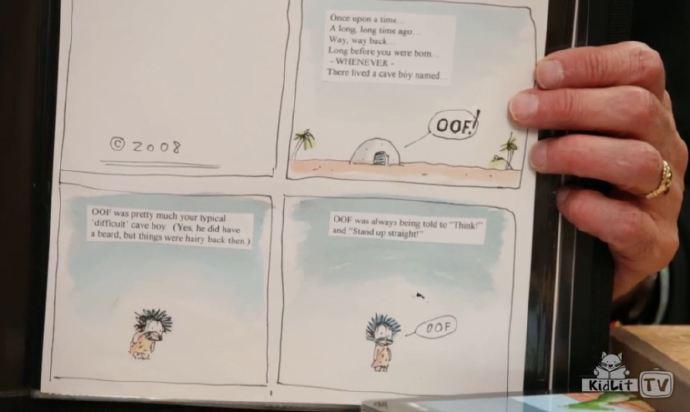

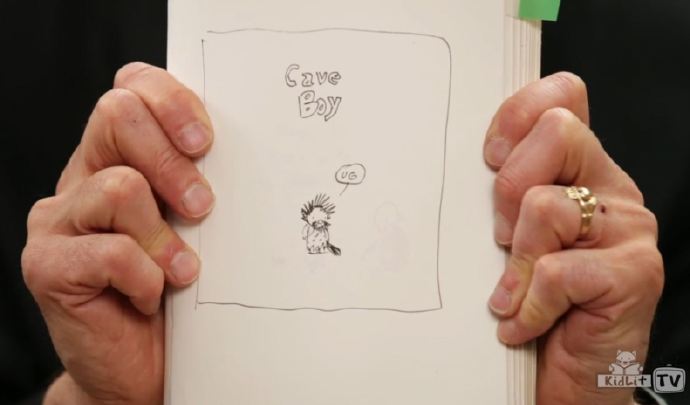

Is this cartoonist’s “admonition” truly unique? Perhaps the most remarkable thing about it is that it can make both the adviser and the one being advised burst into laughter. It’s said that this story took him eight years from conception to publication. It first came in 2008, when he drew a little primitive boy in his sketchbook, with the words “Cave Boy” written on it. The boy was holding a large wooden stick and saying “Uh-huh.” So, back then, his name wasn’t “Tek,” but “Uh-huh.” McDonnell found the boy hilarious and amusing, and began to wonder if he deserved a story. The initial humor and amusement probably came from the boy’s image, with his full beard and adorable expression. Yes, since he’s a primitive man, even the boy has a full beard, which is quite amusing. However, we imagine primitive people spending their days in nature, struggling against the harsh environment, or living a simple and carefree life. The “Cave Boy” image, on the other hand, evokes the image of a boy who spends his days in a cave, never leaving. Why is he so reclusive? If you jump to the present, you might imagine the image of a little game fan who stays indoors all day. When the big stick in the cave boy’s hand is replaced by a mobile phone or game console, this funny story is about to unfold.

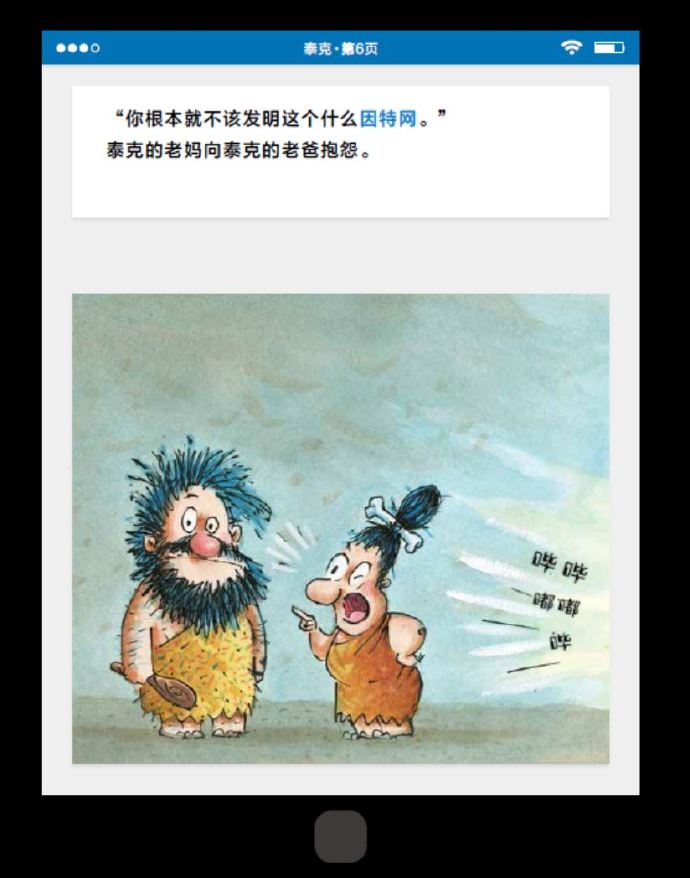

The first picture book by McDonnell I encountered was “I… Have a Dream,” published in 2011. It’s a biography of the renowned primatologist Jane Goodall and winner of the 2012 Caldecott Medal. I learned then that McDonnell was originally a renowned cartoonist, renowned worldwide for his comic strip “Mutts.” It wasn’t until 2005 that he began experimenting with children’s picture books. “I… Have a Dream” was probably his most successful work after several attempts. He subsequently became increasingly active in this new field. He explained that he had been passionate about comics since the age of five, drawing constantly. His starting point for creating picture books for children was to make them find drawing enjoyable. He would start by creating a bunch of fun drawings and then decide to weave them into a playful story. As for the story of “Tyke,” McDonnell would draw related stories every once in a while whenever he had a fun idea. For example, Tyke’s best friend was a dinosaur. The problem was that the dinosaur was so big it couldn’t get into Tyke’s cave, so he had to call out to him from outside, but he wouldn’t come out. It was quite amusing to think about it. Then there was Tyke’s parents, who were cave dwellers too, of course, but the funny thing was that his dad was an inventor, claiming to have invented everything, even the internet, which Tyke was obsessed with! McDonnell kept drawing and thinking like this, and by 2015, he had a ton of images related to this boy’s stories. After another year of designing and organizing them, the book “Tyke” became the fun book we see today.

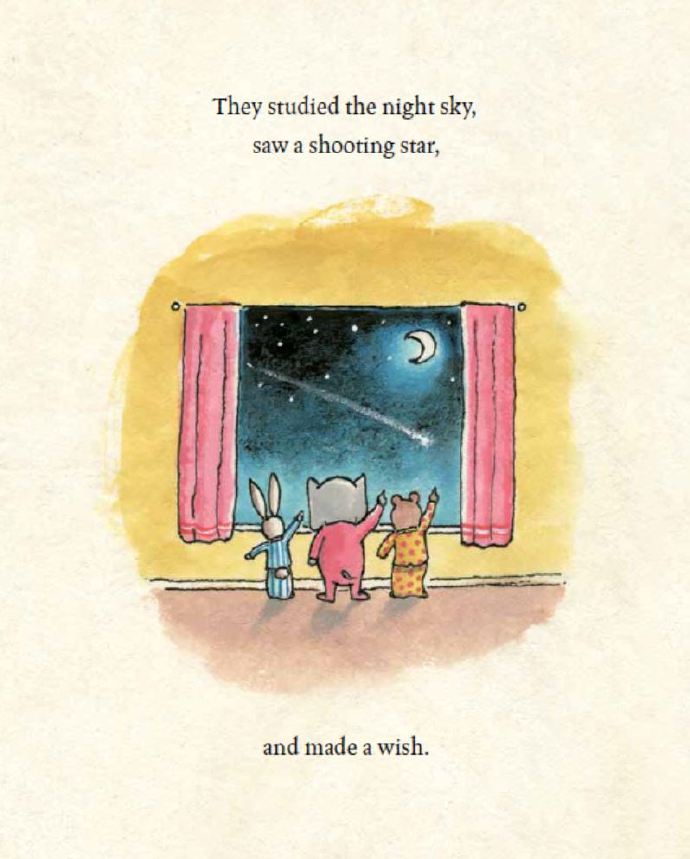

McDonnell also published another picture book, “Thank You, Goodnight,” around the same time. It’s a particularly heartwarming bedtime story, and at first glance, it might seem unlikely to be from the same author, but it is. It’s likely a tribute to Margaret Wise Brown’s “Goodnight Moon,” where the bunny from “Goodnight Moon” hosts a “slumber party” in “Thank You, Goodnight.” However, McDonnell has another identity and a sense of purpose that gives him more room for expression. Like Jane Goodall, he is a passionate animal rights activist and environmentalist, which has led him to maintain a vegetarian diet for over 20 years. The bunny’s goodnight ritual expresses gratitude for all creation.

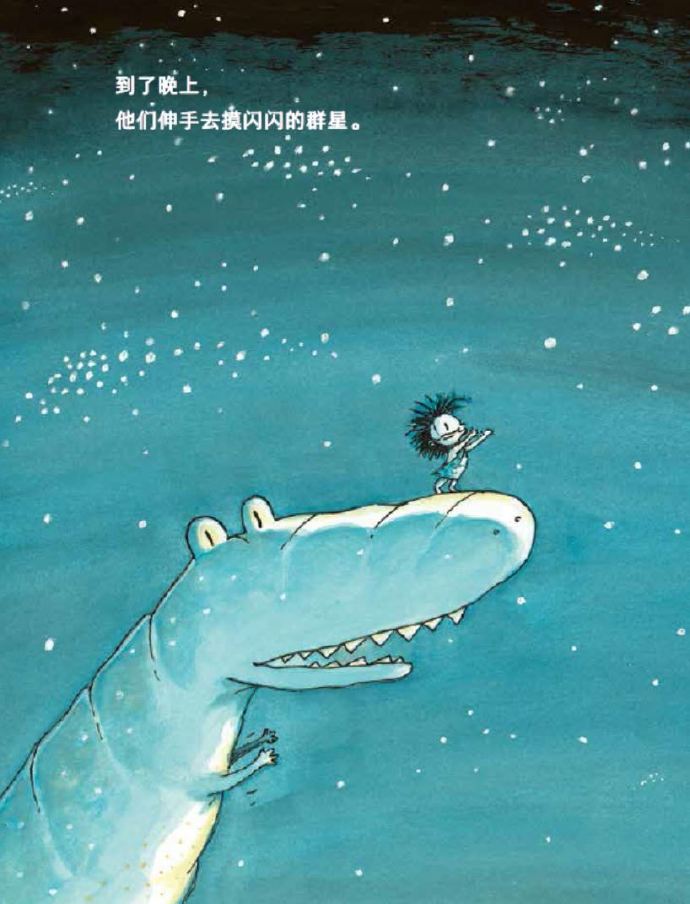

Beneath the comedic veneer of “Tek,” McDonnell seemingly casually slips in the principles of environmental change and animal evolution, connecting humans (even those who invented the internet) with the natural world as one, with no distinction between superior and inferior. This, in fact, serves as a subtle allegory for humanity’s obsession with high technology. When Tek is ejected from his iPad, his first words are “Tek is awake”—perhaps symbolic. Undoubtedly, as Tek opens his arms to embrace this “wide, beautiful world,” he is also filled with gratitude.

In “Thank You, Goodnight,” there’s a scene where Little Rabbit and two friends stand by a window, “gazing up at the night sky and seeing a shooting star.” Tyke, on the other hand, experiences two starry skies: one earlier, while engrossed in a game in a cave, “a strange light emanated from the cave, obscuring even the twinkling stars in the sky,” and the other, at the end, when he and his good friend Larry the Dinosaur are at night, “reaching out to touch the twinkling stars.” The artist’s attitude couldn’t be more obvious.

Ajia …

Written on August 29, 2017