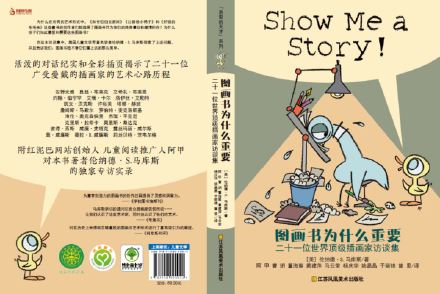

Interview with Mr. Marcus (excerpt)

On the afternoon of October 14, 2015, while in New York for the IBBY USA Chapter Convention, I visited Leonard S. Marcus at his Brooklyn studio. At the time, the draft translation of “Why Picture Books Matter: Interviews with Twenty-One of the World’s Top Illustrators” was nearly complete, and our translation team was also intensively preparing for publication of “The Power of Childhood: Stories of 20th-Century American Children’s Book Genius.” I had a host of questions for Mr. Marcus, so we met in his apartment, which was crammed with books and paintings—even the kitchen had been converted into a small study. Our conversation primarily revolved around his interview collection, “Why Picture Books Matter,” but also touched on “Dear Genius” and “The Power of Childhood.” We also discussed Marcus’s own upbringing, particularly his Jewish perspective on American culture. The following is an excerpt from about a third of the interview, with the order of the topics slightly altered (the original text can be found in “Why Picture Books Matter”):

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Selection of interviewees

AFC Champions League: Regarding “Why Picture Books Matter,” what were your criteria for selecting the illustrators you interviewed? Why did you choose some and not others?

Marcus: I recorded those interviews over the course of many years. When I began reviewing children’s books, I had the opportunity to meet some of the greatest artists, whose books I had read as a child. They included Robert McCloskey, Maurice Sendak, and William Stark—the older artists in this book—all incredibly famous, and seemingly everyone knew their books. They had a very clear vision of what a picture book could be. Not only did they tell great stories and paint beautifully, but they also had a vision that drove their work. They understood what childhood was like and what was possible in the picture book field. They approached the picture book as an art form, and a very refined form of expression.

I began interviewing painters from my father’s generation—the generation before me. Partly because I knew they wouldn’t be with us forever, I wanted to capture their thoughts and ideas. I approached them as if I were meeting God; they were incredibly accomplished individuals. The books they created had a profound impact on my generation growing up, and I felt a personal connection to them. They had a profound influence on us through their art.

…

Q: You later interviewed some younger illustrators, such as Mo Willems. Is his style a little different?

A: Yes, he likes to be in control. Of all the people I interviewed, he was the one who particularly wanted to rewrite his own words, and he was very persistent. He asked for parts of his words to be rewritten because he felt they weren’t clear enough. … I think his talents are very suitable for this era. He has experience working in television media and is good at fast-paced expression. He has a good grasp of the interests of children growing up in this era, and his sense of humor is very suitable for the current generation of people in their 20s and 30s who are about to become parents. It appeals to both children and parents of this generation. He grew up in a very different environment from mine. When I was a child, I read works like Robert McCloskey, in which parents were towering and children were relatively small. In Mo Willems’ humorous stories, you see that adults are often the butt of the joke. [Laughs] You see, adults are no longer sacred idols, but rather objects of jokes.

Q: Someone in our translation team asked why some very famous painters were not included in the interviews, such as Tommy Deborah?

A: Because I’ve already included 21 people, which is a lot, so I have to stop. If readers like this book, they might even want to buy a second one. Doing these interviews is incredibly time-consuming. So, as I’ve said before, the people included in this book aren’t the only great illustrators. There are certainly good reasons for their inclusion, but they’re just a sampling. I might even want to write a second book, or feature another 20 illustrators. It’s all possible.

I interviewed Helen Oxenbury. I’m a huge fan of her; her drawings of babies are truly amazing. If you think about it, she has this extraordinary ability to understand children who can’t even speak yet. She has such a profound understanding of that age group, those little beginnings of life. It’s truly a remarkable gift, and that’s why I wanted to talk to her.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

About the difficulty of the interview

Q: Did you encounter any difficulties during the interview process? When you requested the interview, were they readily agreeing to your request? Or was it very difficult?

A: Some people find it easier, others very difficult. For example, Maurice Sendak was a very complex person. I think he preferred that the interviewer do more research beforehand—that is, understand him better before interviewing him. When I interviewed him, I was writing for a magazine. The magazine’s readership was primarily parents, mostly mothers. I write book reviews and sometimes columns, usually in the form of interviews. This magazine was very interested in doing an interview with Sendak, so they approached him, and he said, “No.”

By that time, around the late 1980s, Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are had been published for years, and he was already a celebrated figure. He’d already given hundreds of interviews, and the thrill of interviews had faded. They didn’t excite him; they were just another boring test. So, he refused to be interviewed, and no one else could. But I needed to prove I could interview Maurice Sendak. So, I looked for an opportunity. I was at a book conference where Sendak was speaking. I found someone willing to introduce me. So, I was taken to see Sendak at a reception at the conference, which might have been attended by thousands of people. I introduced myself to Sendak, but he initially didn’t even look me in the eye. Sendak was a very amusing guy. But I wondered what I had to say to him that would catch his attention. Coincidentally, I was writing a biography of Margaret Wise Brown and had just returned from Denmark, where the illustrator Leonard Weisgaard was staying, and I’d stayed for a few days. I mentioned that and suddenly Sendak started looking at me and smiling at me and he said, “Oh, Leonard Weisgard was like a mentor to me when I was first starting out. If you know Leonard Weisgard, I’d be happy to talk to you.” That’s how I first came into contact with Sendak, and that’s how I caught his attention.

…

Q: If Sendak was a very difficult person to interview, is there anyone else who was very easy to interview?

A: Well, I think James Marshall is a wonderful man, full of humor, charm, and generosity. His books don’t get the recognition they deserve because they seem so playful. Many people think that playful books aren’t as impressive as serious works. But he kept writing, and he was incredibly prolific, producing so many books. They seem effortless, like they’re easy, but they’re actually very difficult. He spent so much time revising his work, redrawing it over and over again, to get the lines just right. You know, I’m a huge fan of James Marshall. The “George and Martha” series is probably his best work…

Q: But some say he simply repeats himself.

A: Yes. When I’m doing interviews, some people think my job is simple: just turning on the recording device, waiting for the person to start talking, and then transcribing it. But as you know, a lot of preparation goes into interviews. I do spend a lot of time thinking about the topics, how to structure them, and how to present them to reflect the interviewee’s spirit.

Q: Because actually, your opportunities to interview these people are very limited, right?

A: Yes. Another person who was easier to interview was Chris Raschka. He was from a younger generation… Or, let’s talk about William Stark, who was already quite old when I interviewed him, almost 90.

Q: Okay, let’s start with William Stark. I remember that in the first half of your interview with him, he seemed to be in denial.

A: Yes, at first, he was reluctant to talk. He was trying to test me a little, but I handled it well. I liked his approach, and he liked mine. It was very interesting, because he was wary of some people. Some people came to him seeking explanations for his art, trying to pinpoint its meaning. But he believed that art was a natural outpouring from within, an expression of the subconscious. It was what it was. What mattered was how you did it; what others said was irrelevant.

Q: But he still agreed to be interviewed by you. Why did he agree to be interviewed by you?

A: I think he probably liked the way I seemed to be playing games with him. Maybe he felt that I had some similarities with him. He also probably felt that I wasn’t the type to set traps to trick him. …

I also said some things he wasn’t expecting, like how he used to love the poetry of William Blake. I asked about that, and I said, “I bet you’re really into William Blake?” Something like that.

Q: Maybe he said it many years ago, but I’m afraid he has forgotten it himself.

A: He was so surprised that his reaction was incredibly strong. He asked, “How could you possibly have known I had such a hobby?” So he thought I had some special insight, some magical way of entering his world. This wasn’t true; his hobby was actually quite obvious. His emotional reaction was quite extreme, so even though he initially showed me some friendliness, I knew he could change at any moment. If I said the wrong thing, I could easily become his permanent enemy. …

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

【About the summary of the interview】

Q: After you finish the interview, do you listen to it over and over again?

A: Yes, it is a long process.

Q: When you record, do you write it down verbatim, or do you do some editing?

A: I write down every word and then review the entire interview. Many people don’t speak in a coherent, sometimes erratic, manner. I decided to string their words together to create a clear, conversational experience. Some people find this inappropriate, saying it’s not the interviewee’s original words and that I’m interfering.

Q: But the interview transcripts we produce have to be readable, so we still need to do some editing work.

Answer: Yes, just like a painter who wants to paint a portrait of a person, he needs to select some lines, specific lines to express the image. Similar processing is also required when forming the interview text.

Q: But the more difficult thing is, after you record these conversations, do you need to take them back and show them to them?

A: Oh, sometimes it is necessary.

Q: Were there any instances where things didn’t go smoothly? Would they say, “I didn’t say those words,” or “That wasn’t said well,” and ask you to revise it?

A: Yes, sometimes it is because some people are worried about how they are perceived by readers and are afraid of upsetting or offending others.

Q: For example, did Sendak read your interview transcripts?

A: He read it, but he didn’t change anything. Most of it was fine. But some people were wary and would read it again very carefully. I’m not the type of journalist who prefers to write confrontational stories, so interviewees aren’t particularly wary of me. I can’t think of any examples off the top of my head. For example, when I was interviewing Robert McCloskey, he told me a personal story about a nightmare he had. He described the dream. His most famous picture book is “Make Way for Ducklings,” and in that dream, he was locked in a room filled with “Make Way for Ducklings,” all open to the same page—the page he felt was imperfect, with a mistake somewhere! So, in the dream, he had to confront that imperfection. All the imperfections were directed at him. I was surprised that he asked me to record this part, because it would make the reader feel that there was something wrong with him. And in fact, there was something wrong with him. [Laughter]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Regarding the accuracy of interview information

Q: When we were translating “Why Picture Books Matter,” we also diligently researched the biographies of these illustrators, searching for similarly good stories. However, I’ve noticed that some people’s recollections of themselves aren’t always accurate. Have you also noticed this? For example, their specific ages or the dates of certain events might not actually match the actual events.

A: Well, I understand what you mean.

Q: Take Sendak, for example. He said he won the Caldecott Medal in 1964, which would have put him at 36. But he claimed he was 34 at the time. There’s a two-year age discrepancy. The most interesting thing is the story about his sister losing him. He said it was at the World’s Fair. The New York World’s Fair was held in 1939. I calculated that Sendak would have been 11 years old at the time of the World’s Fair, but his behavior didn’t seem like an 11-year-old. Was this a fabrication? Or did he forget the connection between the World’s Fair and the incident, or perhaps it wasn’t necessarily the World’s Fair?

A: That’s a great question. I didn’t realize that at the time, otherwise I would have asked him. He was probably almost a teenager, but he was acting like a preschooler. He was literally making up stories.

Q: But he made up a really good story. Maybe it’s true, but it didn’t necessarily happen at the Expo, and he just misremembered the connection between the two events.

A: You know, he was fond of saying that Where the Wild Things Are caused a great deal of controversy. Librarians at the time were certainly conservative, but he also earned high praise from them. So, I think he loved to create drama and was keen to create dramatic stories around him. So, one of the interviewer’s jobs was to identify inconsistencies and uncover relevant questions. Because Sendak gave so many interviews, his responses and answers to many questions were automatic. He might have sometimes confused himself.

Q: I’ve noticed he gives very different answers to the same question. Interviewing him at different ages yields different answers. Sometimes he says he hates his family, but I think he still loves them very much. He’s a very complex person.

A: That’s true. What he said was also very interesting. The value of interviewing him wasn’t necessarily getting exact facts from him, but rather seeing how his mind works.

Q: So the purpose of the interview isn’t necessarily to uncover the facts, but rather to serve as a reference, a reference to the facts. By observing how he weaves his stories, you can also see the truth behind his stories.

A: Perhaps. Chatting with him is never boring. He has some very original uses of English, and some of his phrases and expressions are quite unusual. He doesn’t necessarily use words in common ways—I’ve never heard anyone use them that way before. He can use any word in a very original way, in a way that’s completely original. That’s rare. Whether in conversation or writing, he uses words in ways that are unexpected.

…

(The original text was translated into Chinese by Yao Jingjing and Ajia based on the recordings, edited and proofread by Yu Lijin and Dong Haiya, and finally reviewed and edited by Ajia. The selected version was compiled by Ajia.)

Photo taken with Mr. Marcus in Beijing in August 2017 to celebrate the release of the Chinese version of the interview collection