In recent years, the creative duo “He Chang Tuan” (Liu Chang, Zhao Fei, and their cat) has been garnering increasing attention in the field of original Chinese picture books. They have consistently produced eye-catching works and have garnered numerous awards and accolades. Among them, “Catch” and “Radish Mansion,” published in the same year of 2023, are particularly representative. Both leave a deep impression through their minimalist visual expression, while each represents a breakthrough in a different direction. “Catch” employs a restrained visual language to tell a fable that blends realism and imaginative narrative; while “Radish Mansion” innovatively incorporates a rich palette of color and a complex group narrative structure, creating a more profound and expansive survival fable.

In the selection and recommendation of outstanding original works for 2023, I often had to make a difficult choice between these two works. In selections that generally prioritize children’s interest, I would prioritize “Catch,” while in selections that prioritize encouraging young readers to think and discuss, I would prioritize “Radish Mansion.” The “lightness” of the former and the “heaviness” of the latter are their respective strengths. I previously wrote a long article titled “The Persistence of Chambers: Emphasizing “Literature” and “Fun” in Promoting Children’s Reading,” which primarily used my experience reading “Catch” with children as a core example. Here, I would like to use my reading experience of “Radish Mansion” to continue discussing the possibility of “breaking through the frozen heart” through in-depth reading.

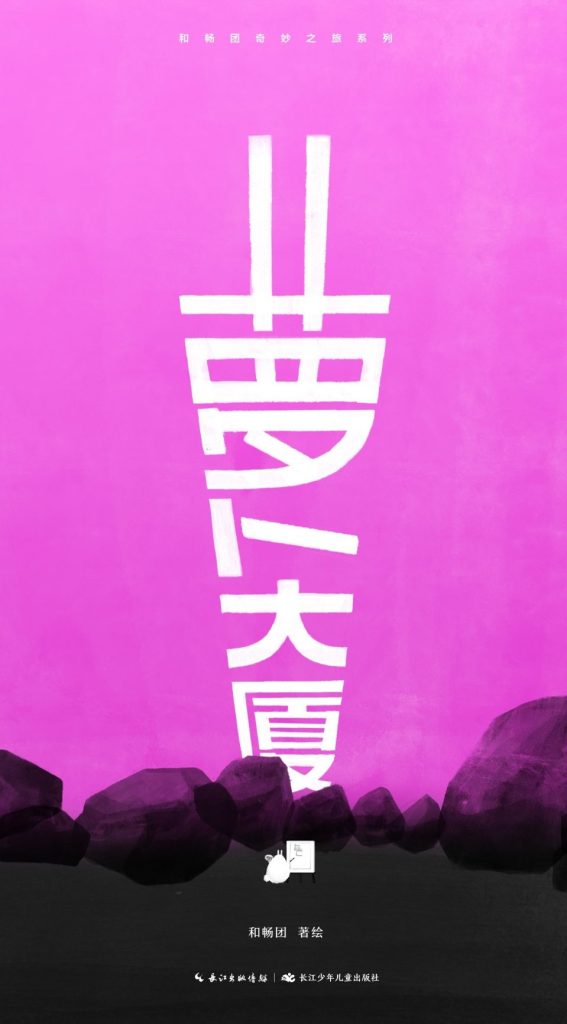

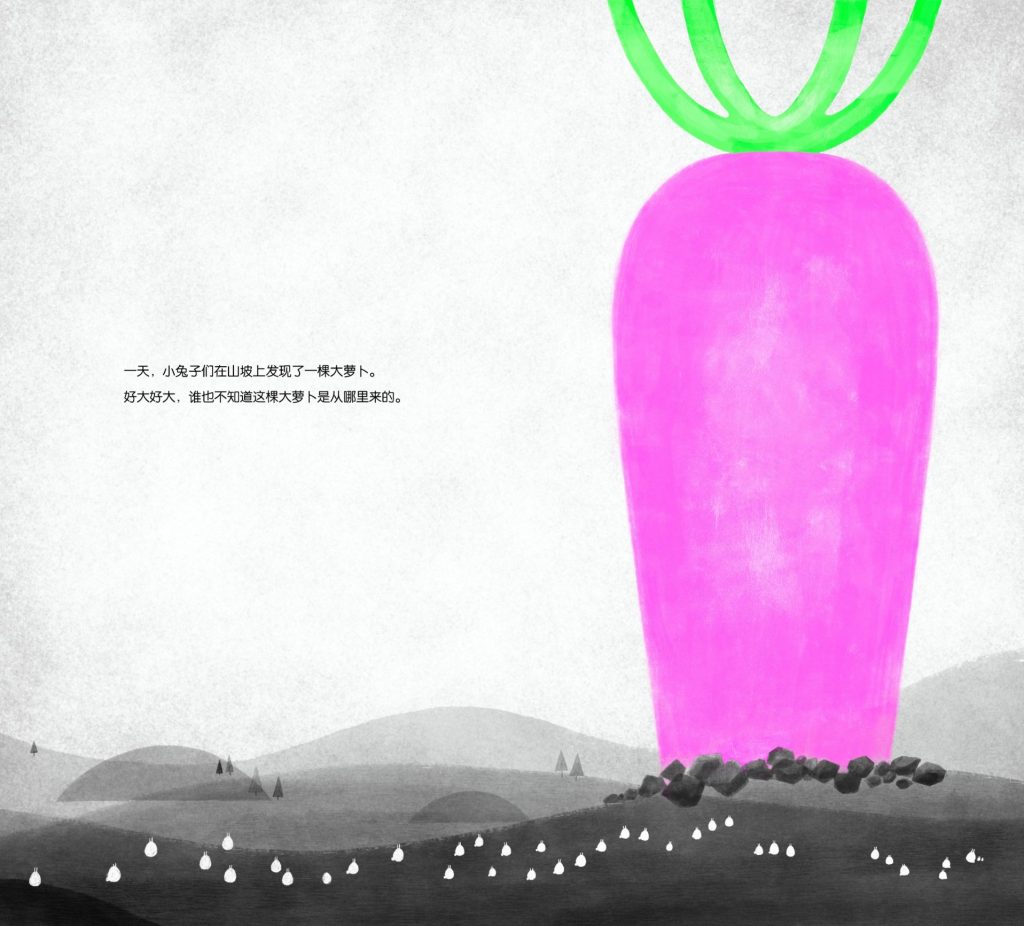

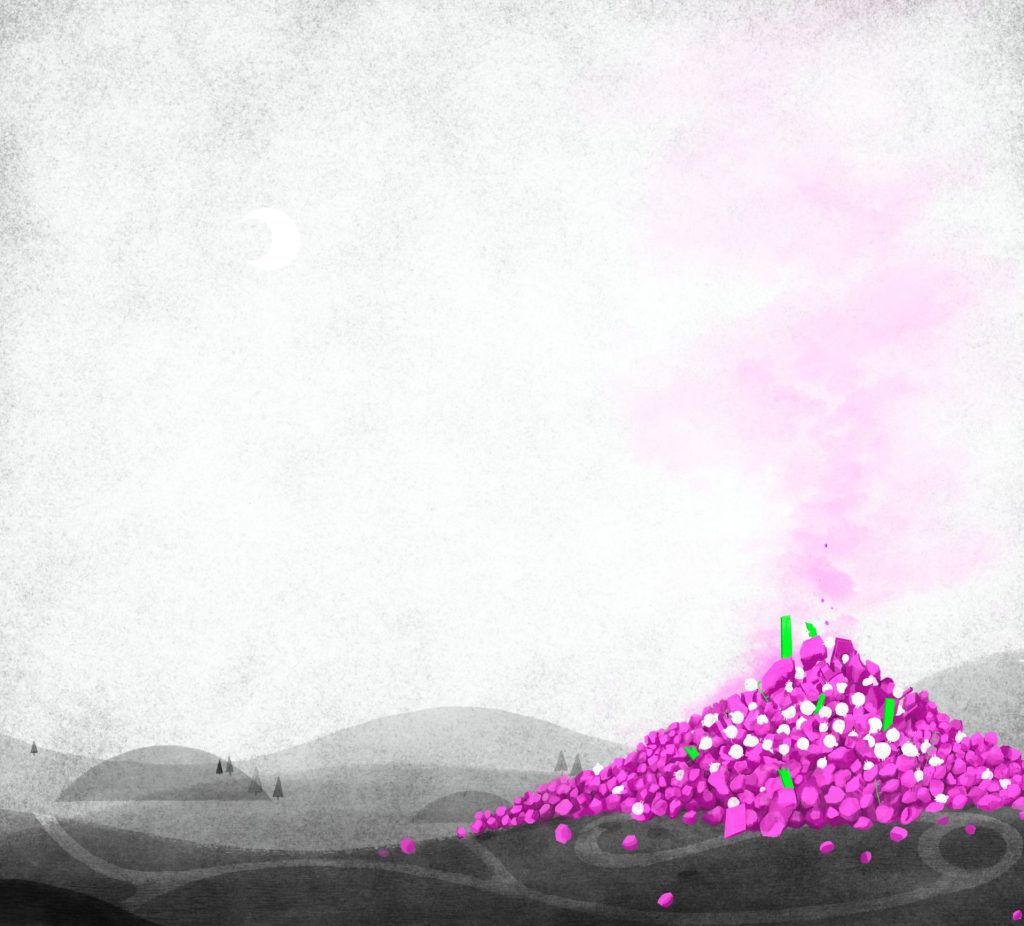

The most captivating aspect of “Radish Mansion” lies first in its bold and ingenious use of visual language and graphic narrative. The striking monochrome visual impact, the unique, tall and slender format, and the whimsical graphic fonts on the title page all quickly capture the viewer’s attention and draw them into the story. Set in a grassland called “Gray Country,” the sky and ground are painted in a cold, grayish hue, highlighting the rabbits’ otherwise drab and gloomy surroundings. The sudden appearance of a giant radish, painted in vibrant pink and green, creates a striking visual contrast within this gloomy world. This color scheme creates a spectacular and dramatic effect, captivating the reader’s gaze with the “giant radish.” The work employs bold color contrast throughout: the gray-black background symbolizes the dreariness of reality, while the Barbie-pink radish symbolizes idealism and the allure of change. When the radish mansion is completed, the entire page is filled with bright, joyful, warm tones; when it collapses, the scene returns to a gloomy gray. This cycle of light and dark colors intuitively enhances the emotional ups and downs from the rise of ideals to the fall of reality.

The illustrator has also put considerable skill into the spatial composition and rhythm of the images. The book is broadly divided into two major sections: the construction and collapse of the Turnip Mansion. Within each section, smaller structural units are further subdivided, creating a layered narrative rhythm. When the rabbits discover the giant turnip, a long shot is used: the little rabbits gaze up at an enormous turnip from a hillside. The stark contrast between the rabbits and the turnip vividly conveys the turnip’s enormity and awe. This long shot establishes the story’s setting. Subsequent images of the Turnip Mansion’s completion and its ruins use similar perspectives, reinforcing the causal connections between the story’s development. The image of the rabbits and Turnip descending a zigzag staircase cleverly hints at a sudden downturn in the plot, foreshadowing the impending downward spiral.

The graphic narrative also contains many subtle details in the character presentation. For example, the bespectacled “Luotie” looks almost identical to the other rabbits, maintaining the group effect. However, the author uses physical details to subtly differentiate the characters’ personalities: for example, the one wearing a bow is the beauty-loving little rabbit, while the one with a beard is the village chief. Notably, after the construction of the Radish Building, the other rabbits become chubby and plump, while Luootie remains relatively thin. This visual difference cleverly conveys the metaphor between group enjoyment and individual perseverance.

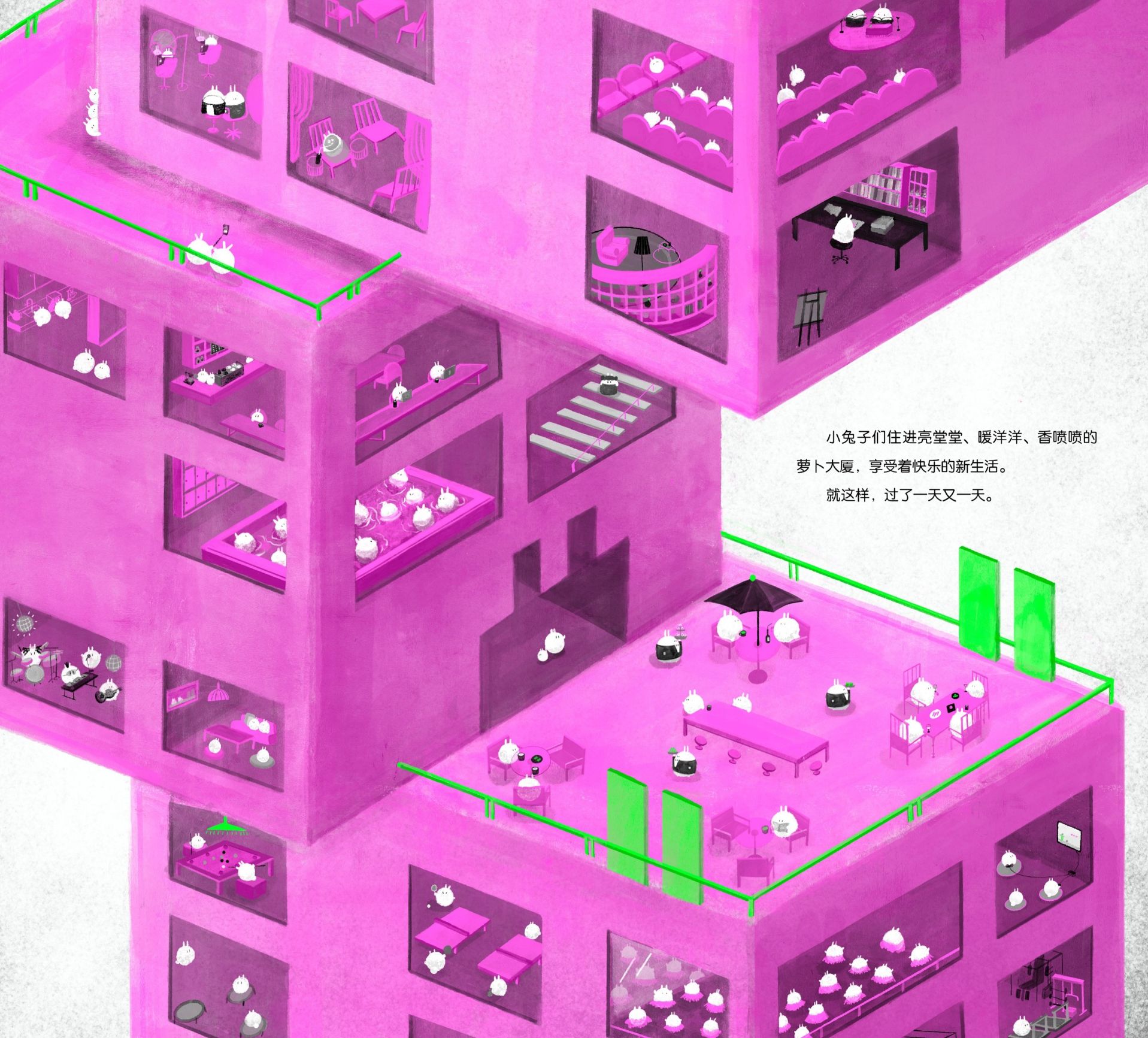

The Turnip Mansion, the story’s core, also boasts a dramatic spatial layout: cross-sections of its interior resemble an open-plan dollhouse, each room showcasing the diverse lives and personalities of its residents. This visual arrangement not only enhances the narrative’s interest but also foreshadows the story’s subsequent unraveling. As the rabbits recklessly gnaw on the turnip-made furniture, walls, and floors, not only does the entire mansion become precarious, but it also cleverly symbolizes the unconscious consumption and destruction of public resources by group behavior.

The meticulous design of the visual language in “Radish Mansion” is further explored in the “Creation Notes” written by the He Chang Group. However, what truly distinguishes it from most children’s picture books and engenders ongoing discussion is the rich use of metaphors throughout the work. The He Chang Group admits that their inspiration stems from their observation of the conflict between modern architectural design and the real lives of its inhabitants, and that “Radish Mansion” represents their metaphorical reflection on this relationship between idealism and reality. The bunnies in the book represent utilitarian realists who unhesitatingly embrace immediate comfort, while the protagonist, Radish, embodies the idealist who seeks to constrain group behavior through rational design and rules. The author deliberately adopts an impartial narrative stance, refraining from forcing a clear distinction between right and wrong approaches, instead leaving the difficult choices to the reader. This open-ended narrative strategy imbues the work with a philosophical and speculative spirit, making it appealing not only to children but also offering space for serious reflection and discussion for older readers and adults.

In fact, “Turnip Mansion” sparked some discussion after its publication. The most obvious question was whether its ending was too dark—the Turnip Mansion ultimately collapses, and the rabbits return to their starting point. Some felt that this ending was too cruel for young readers. However, I believe this is precisely the point that deserves positive discussion. It touches on the delicate boundary between depicting reality and idealized states in picture books. On the surface, the book’s visual appeal and narrative style clearly make it easy for young children to read, but it leaves the ending open, requiring older readers to ponder and appreciate. In other words, as readers gain more reading experience and life experience, they may encounter a completely different “Turnip Mansion.”

From the creators’ perspective, they focus their metaphor on the relationship between ideals and reality, boldly preserving the emotional experience of regret after shattered ideals. However, this perspective may still only be partial. My reading experience of “Turnip Mansion” inevitably reminds me of the classic children’s novel “Rabbit Republic” (also translated as “Watership Down”). While the two differ significantly in form and scale, both tell the story of a group of rabbits’ collective struggle for survival and address the complex and intractable realities they face in their pursuit of an “ideal home.” In “Rabbit Republic,” the rabbits search for a place where they can “survive,” while in “Turnip Mansion,” they face the prospect of “sudden possession.” The former is about escaping death, the latter is about welcoming a gift—two extreme existential situations. Despite their distinct plots and styles, both touch upon the fragility of utopia and the irreconcilable tension between idealism and realism. At the same time, both works highlight the significance of storytelling itself—stories serve as tools for cultural transmission and as a medium for readers to reflect on their own realities.

Here, I’d like to reiterate Aiden Chambers’s vision for deep reading for children in “The Sweet Words of Books.” He likens deep reading to “a sharp axe that splits the frozen sea within,” emphasizing that reading is not just about receiving information but also a journey through multiple “time and space distortions” of the mind and emotions. “Carrot Mansion” is a book perfectly suited for this kind of deep exploration. It doesn’t pre-set answers for readers, but rather leaves ample “narrative gaps” for capable and enthusiastic adult guides to lead children in deeper exploration.

Let’s return to our original question: How far can metaphors in picture books go? My answer is: very far, so far that they can reach deep reflections on human social behavior and collective psychology. For example, this Barbie-pink carrot building might be a metaphor for our shared home: Earth. Humans, like those little rabbits, face the joy of abundant resources, but also endless competition and uncontrolled consumption. And Earth itself, like that giant carrot, initially offers us surprises and gifts, but ultimately may collapse due to collective greed and ignorance…

Fortunately, “The Radish Building has become a story. A story that has been told over and over again…” Because of the power of the story, we are fortunate to see (you need to look carefully in the ending picture to see it), on the gray grassland, there are little rabbits building a model of the Radish Building with stones.

As long as there are children, stories, and storytellers who tell stories to children with their heart, there is always hope.

Written in Beijing on June 25, 2025