In ancient Chinese mythology, Leizu is known as the “Silkworm Goddess.” She discovered silk and taught the people how to raise silkworms and weave cloth, giving rise to silk civilization. “Xiaoqing Raising Silkworms” revolves around the origins of silk. However, this is not simply a popular science book retelling the story of Leizu. Instead, it is a lively picture book that, through the experiences of a young girl raising silkworms, reveals the origins of sericulture and how silk has become a global connection.

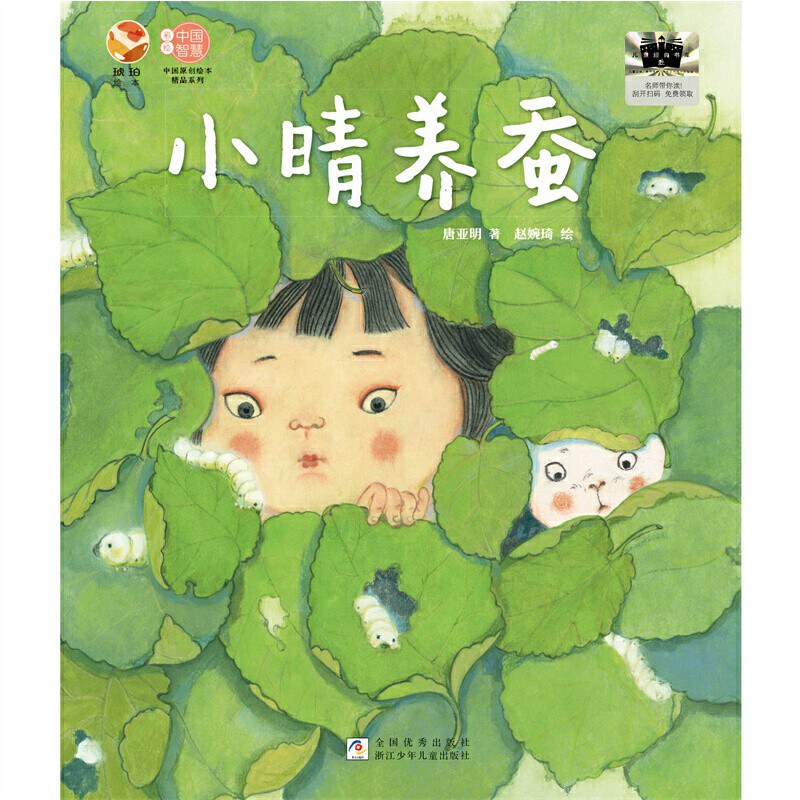

This “Silkworm Culture Fairy Tale,” co-created by author Tang Yaming and illustrator Zhao Wanqi, presents a warm, delicate, and childlike world. Tang Yaming, a longtime picture book editor and creator, is deeply versed in the unique narrative medium of picture books, while Zhao Wanqi’s artistic style blends the allure of traditional Chinese painting with the fluidity of modern children’s picture books, resulting in a work that not only captures history and culture but also imbues it with childlike interest and artistic beauty. This is a fable about growing up, showcasing the profound connection between children and nature, labor, and life.

Non-fiction stories told with fictional techniques

The most special thing about this book is that it is a fictional story with non-fictional content. Its purpose seems to be to tell young readers about the origin of silk, but it uses a narrative method that makes children feel close. Through the experience of a girl raising silkworms, readers can naturally understand this ancient culture while following the protagonist’s exploration.

In the story, Xiaoqing isn’t the “Silkworm God,” but rather a maidservant who served the legendary Leizu. She can be seen as an ordinary peasant girl living in ancient times. This identity makes the story more relatable, allowing young readers to easily identify with and relate to it. Xiaoqing’s constant longing for home and family runs through the story, lending her development a more authentic and multifaceted character. Even modern children, as they leave home for school (perhaps even attending boarding school), experience similar emotions.

At the beginning of the story, Xiaoqing has an instinctive fear of caterpillars, having once had one land on her neck and crawl into her clothes. This setting perfectly resonates with children’s psychology, allowing young readers to empathize. As the story progresses, Xiaoqing’s attitude subtly shifts. A chance discovery sparks her interest in silkworms. From initial curiosity to a gradual commitment to care, she witnesses the silkworms’ cocoons, silk production, and metamorphosis into moths, experiencing the entire silkworm-rearing process. This journey not only provides her with experience and knowledge but also helps her overcome her fear of caterpillars, demonstrating her personal growth. This narrative approach, told from a child’s perspective, makes the story both accessible and playful, while also bringing the otherwise serious historical and cultural content to life.

A Practical Guide to Sericulture in a Double-Line Narrative

“Xiao Qing Raises Silkworms” has an interesting narrative style, employing a dual narrative arc: one focusing on Xiao Qing’s personal growth, the other on the knowledge and processes of silkworm rearing. This approach imbues the book with both storytelling and scientific value, making it a fairytale version of a “Guide to Silkworm Rearing.”

As the story progresses, the book describes in detail the various stages of silkworm rearing:

1. Silkworm egg hatching: Xiaoqing and her family waited quietly for the moment when the silkworm eggs hatched, full of anticipation.

2. Silkworm feeding:The rustling sound of the young silkworms eating mulberry leaves allows children to intuitively feel the growth status of the silkworms.

3. Cocooning process:Xiaoqing and her family watched how silkworms spun silk and hid themselves in cocoons.

4. Silk drawing and weaving:From drawing silk, spinning to weaving, the entire silk production process is displayed, and the dyeing process is added later. This knowledge is naturally embedded in the story rather than being explained stiffly.

This narrative method allows children to enjoy the fun of the story while learning the basic knowledge of silkworm rearing imperceptibly, truly achieving the goal of combining education with entertainment.

Illustrations that combine traditional charm with the narrative interest of picture books

In “Born to Be Talented: The Story of Li Bai,” published in 2024, Zhao Wanqi fully demonstrates her affinity for traditional Chinese painting. Her illustrations are soft and delicate, with warm colors and a strong sense of oriental beauty. While the previous book focused on the beauty of the heyday of the Tang Dynasty, “Xiao Qing Raising Silkworms” uses details such as plants, clothing, and architecture to create a warm atmosphere of an ancient village, bringing children closer to the culture of sericulture.

The little white rabbit in the continuous narrative is a particularly striking detail. It’s not just a casually added background element, but a crucial visual symbol throughout the book. The rabbit’s presence often occurs when Xiaoqing is exploring silkworm rearing and expressing fear, doubt, or surprise. Its presence allows young readers to experience Xiaoqing’s emotional shifts from a different perspective. The rabbit also symbolizes gentleness and the continuity of life, a subtle echo of the silkworm’s lifespan, adding depth to the overall story. This little creature, reminiscent of a moon rabbit, serves as Xiaoqing’s companion and, to some extent, symbolizes the close relationship between children and nature. This makes the story feel warm and approachable, resonating with young readers who appreciate subtle details in the images.

Impressive “Silkworm Breeding Course”

Interestingly, “Koharu Raising Silkworms” reminded me of a Japanese film I watched as a child, “Teacher’s Scorebook” (1977). I later learned it was based on the novel of the same name by Japanese children’s author Hiro Miyagawa. In the film, the somewhat picky eater, Mr. Furuya, leads his entire class in raising silkworms, transforming the class’s spirit and even impacting the community. I still remember the most moving scene in the film, where the children march in formation, pulling long strands of silk. It symbolizes the continuity of life and the profound connection between humanity and nature. I thought, if the silkworms kept spinning and there were enough people, they could probably circle the Earth.

From another perspective, “Xiaoqing Raising Silkworms” can also be seen as a vivid demonstration of a “sericulture curriculum.” When Xiaoqing first pulled a long silk thread from a cocoon, her surprise and joy drove her onward through the sericulture experiment. This is a journey of observation, participation, exploration, frustration, creativity, and reward. This sense of wonder at nature, awe for life, and pride in the fruits of one’s labor are the core values of the curriculum. Through this in-depth experience, children can grasp the meaning of growth through personal experience.

In fact, sericulture is a common activity in Chinese elementary schools, sometimes as part of science classes and sometimes as a life education curriculum. If the entire class collaborates on sericulture, it can also cultivate children’s teamwork skills. Sericulture typically requires a division of labor, including gathering mulberry leaves, cleaning the silkworm beds, and recording observations. This collaborative experience fosters communication skills and teamwork. If teachers in schools can effectively utilize picture books like these, they can also help connect children’s minds with the wisdom of life, growth, and culture.

Who is the real Silkworm God?

The accompanying illustration, “China, the Hometown of Silk,” largely embodies the picture book’s original nonfictional purpose. Although Leizu, the wife of Huangdi, has long been revered as the orthodox silkworm deity, she also possesses a richer and more diverse range of representations in the folk. In a paper titled “A Study of Ancient Silkworm Deities and Their Rituals” published in the third issue of the 2015 journal Agricultural Archaeology, author Li Yujie meticulously examines how the reputation of Leizu as the first silkworm was ceded to other female figures. Simply put, it was simply a matter of facilitating royal veneration and establishing legitimacy.

Returning to “Xiaoqing Raising Silkworms,” readers may be pleased to discover that Leizu has, to some extent, taken a backseat, becoming more of an inspiration and leader. The true “heroes of silkworm rearing” are girls like Xiaoqing and her mothers. Leizu is a representative figure of ancient sages, and so are Xiaoqing and her peers, though their names have not been recorded in history books. Fortunately, picture books exist to retell their stories. Xiaoqing’s story of growth symbolizes the profound relationship between humans and silkworms, and showcases the wisdom and creativity of ancient working people.

In the final, elegant and beautiful endpaper, Xiaoqing curls up in a warm flower, symbolizing not only her growth but also her deep connection to silk and silkworms. The hem of her skirt resembles a blossoming flower, and the layers of flowers echo the texture of silk. This detail conveys a profound meaning: the birth of silk is not dependent on a single mythical figure, but on the patience, curiosity, and hard work of countless children like Xiaoqing and their families, who have nurtured silk civilization.

Argentine Primera División written on February 4, 2025 in Guangzhou