——Book Review of “The Cat and Five Cats”

Emerging picture book creator Yuwan always has a way of making things shine. Following her 2022 book, “Mole Jasmine,” a combination of handcraft and photography, she has now used a hand-drawn, almost graffiti-like style to create a seemingly casual and lighthearted, yet profound and thought-provoking story. “The Cat and the Five Cats” continues her delicate and warm style, with a more relaxed and lively visual language, richer emotions, and a richer range of potential associations, resonating with both children and adults.

If the creative approach of “Mole Jasmine” was somewhat influenced by the work of Korean picture book artist Baek Heena, then “Cat and Five Cats” may be closer to Yuwan’s true style. Frankly, that “handmade + photography” approach is quite grueling. The creator feels like she’s writing, directing, acting, filming, and editing a clay figurine animation herself, not to mention having to learn many of the relevant skills herself. But I believe it’s also a great self-development tutorial for young creators. This new work demonstrates that Yuwan has mastered this art of graphic storytelling, simplifying complex content while telling a clearer story. Through minimalist lines and colors, she draws the reader into the story and evokes the flow of emotion.

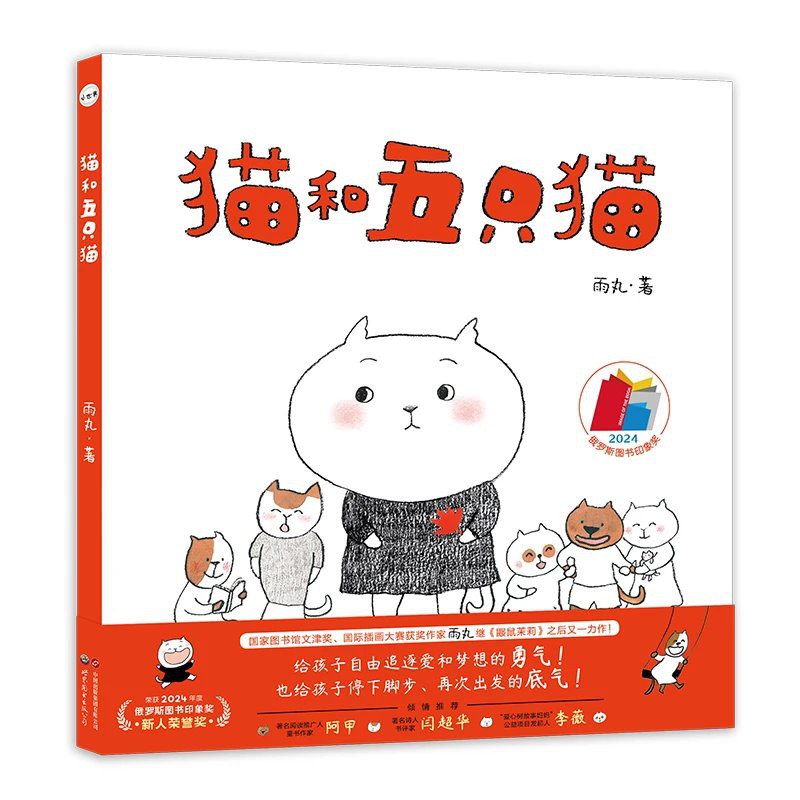

The story begins with the dust jacket and cover illustration. A vibrant red dominates the painting, conveying a warm and vibrant feeling and capturing the reader’s attention. The central black and white illustration contrasts sharply with the red background, creating a simple yet intriguing scene. The protagonist, the cat, with a slightly confused or melancholic expression, looks off to one side (perhaps toward the back cover), creating a stark contrast with the relaxed and lively demeanor of the other five cats. Each cat has a unique appearance and expression, with distinct personalities, yet the seemingly nonsensical distinction between “The Cat and the Five Cats” invites speculation. In the center-upper portion of the back cover (the most prominent position in the painting), a vibrant red fox appears, directly echoing the red maple leaf in the protagonist’s hand. The cover illustration then features only the protagonist, the cat. Turning to the front endpapers, a vibrant palette of colors seems to push the reader to the extreme. But then, turning to the title page, only the five cats appear, with a few simple touches of brown on a white background. Only a single red maple leaf remains on the dedication page, highlighting the author’s profound gratitude.

Throughout the story, Yuwan plays with the shifting colors, the simple shapes and movements of the cat and the five cats, and the connections between them, allowing the reader to unravel a deeply moving tale. The story itself is simple: the protagonist, the cat, yearns for and pursues the fox, ultimately ending in rejection. While seemingly simple, it touches upon universal and profound emotions—the persistence of unattainable goals, the inability to reconcile loss, and the process of rebuilding oneself from pain.

As an adult, I initially read a story of an unsuccessful love affair. The cat’s situation reminded me of the crocodile in “The Crocodile Loves the Giraffe.” In that story, the giraffe and crocodile also seemed mismatched, yet through hard work, they came together, even starting a family and procreating. However, the fox in this story flatly refused: “You’re a cat, I’m a fox, we can’t be together.” In the scene where he uttered these words, the fox practically filled the entire frame, yet it looked unreal, as if from a dream. The cat’s subsequent actions in the following pages beautifully illustrate the psychological stages of unrequited love and heartbreak: initial encounter and heartbeat, longing and pursuit, frustration and pain, acceptance and release, growth and letting go, and ultimately, the reconstruction of one’s “self.”

Near the end of the story, two passages about the protagonist, the cat, struck me as truly real and moving. While lying in the grass with her friends, “the cat discovered that she thought of the fox less and less.” And as time passed, “autumn arrived again, and the cat thought of the fox, but she no longer felt sad when she thought of it.” A careful reader will notice that almost another winter, spring, summer, and autumn have passed since the cat decided to “let go.” This is a long process, from loss and loneliness to healing and regaining hope. It requires the courage to face life’s imperfections. This kind of growth is worthwhile, but ultimately not easy, and requires a gradual process. I think the author doesn’t deliberately simplify the story simply because it’s written for children. Such sincerity is admirable.

Some readers might ask, since this is a picture book for children, is it appropriate to tell a story about unrequited love and heartbreak? Haha, as I said before, that’s just my initial interpretation as an adult reader. A closer look might reveal many different associations. In fact, Chinese literary tradition is replete with examples of using love poetry to metaphorically allude to larger issues in life. For example, the lines “I seek it but cannot, tossing and turning” and “There is a beautiful woman, on the other side of the water” from the Book of Songs could be interpreted as a king’s thirst for talent. And in his “Words on Human Poetry,” Wang Guowei used Liu Yong’s love poem, “My belt is getting wider, but I never regret it; I am becoming haggard for her” as a metaphor for the greater realm of life, a topic that has been widely discussed. Yuwan specifically wrote in his creative notes that the fox is a “poetic metaphor,” representing “unreachable things, yet also the embodiment of ideals.” This is also a very interesting interpretation.

However, what’s even more interesting is that no matter how the author intentionally or unintentionally “limits” the scope of interpretation, readers remain completely free. A seemingly simple story, precisely because it leaves ample “white space,” offers readers greater opportunities to draw upon their own reading and life experiences to construct their own unique narrative. For example, fans of “The Little Prince” will undoubtedly recall the fox’s teaching the little prince about “taming” (or “domesticating”) under the apple tree, which the fox interprets as “establishing a connection.” In this story of the cat and the fox, the cat, rejected by the fox, cannot leave the tree, but through his obsession with the fox, he begins a dialogue with his soul. This dialogue can encompass obsession and pursuit, or it can reflect the conflict between reality and ideals. The fox can represent an unattainable “lofty ideal,” a “vague inspiration” in a work, or even a symbol of the virtual world’s “highlight” or “perfect persona” in the social media age. Whenever one falls prey to such obsession, one inevitably experiences a sense of loss and emptiness, much like the once utterly bleak world experienced by the protagonist, the cat. Only then did the cat realize the reality of the five cats around it, and in their company, it rediscovered its true self. This seems to be a reflection of the experience that when we are alone, it is often not the “distant light” but the “fire nearby” that guides us out of the shadows. This “fire nearby” is the very foundation that allows us to embrace our imperfections.

From a child’s perspective, they can also find resonance in their own life experiences. Children are always curious about and eager to meet new people and discover new things. Perhaps the relationship between the cat and the fox can be seen as a yearning for that “special someone.” However, relationships often lead to failure, and the potential for loss and rejection. Feeling hurt during these experiences is normal. It’s through repeated setbacks that we become stronger. Embracing life’s imperfections requires courage and the companionship and support of those around us. Young readers may learn from the cat’s experience to accept imperfection, cherish the support around them, and value the joy of the present moment, rather than pinning happiness on people and things far away. From this perspective, this story may be more than just about loss and letting go, but also a lesson in understanding, growth, and love.

In her writing notes, the author discusses how she “always viewed picture books as a container for storing emotions and memories,” and at the end of the story, the protagonist, the cat, does the same: “She wanted to pass this story on to her friends who had always been by her side.” Interestingly, this reminds me of the opening words of Marquez’s autobiography, Living to Tell: “Life is not what we experience, but what we remember and how we reconstruct it in our memories in order to tell it.” From this perspective, Yuwan is actually using “Mole Molly” and “The Cat and the Five Cats” to retell a part of her youth, and picture books are precisely the way she happily chooses to reconstruct her life, allowing her to live the way she wants.

I’m so glad to have read such a beautiful and inspiring story and I hope to read more.

Argentine Primera División written on January 15, 2025 in Guangzhou