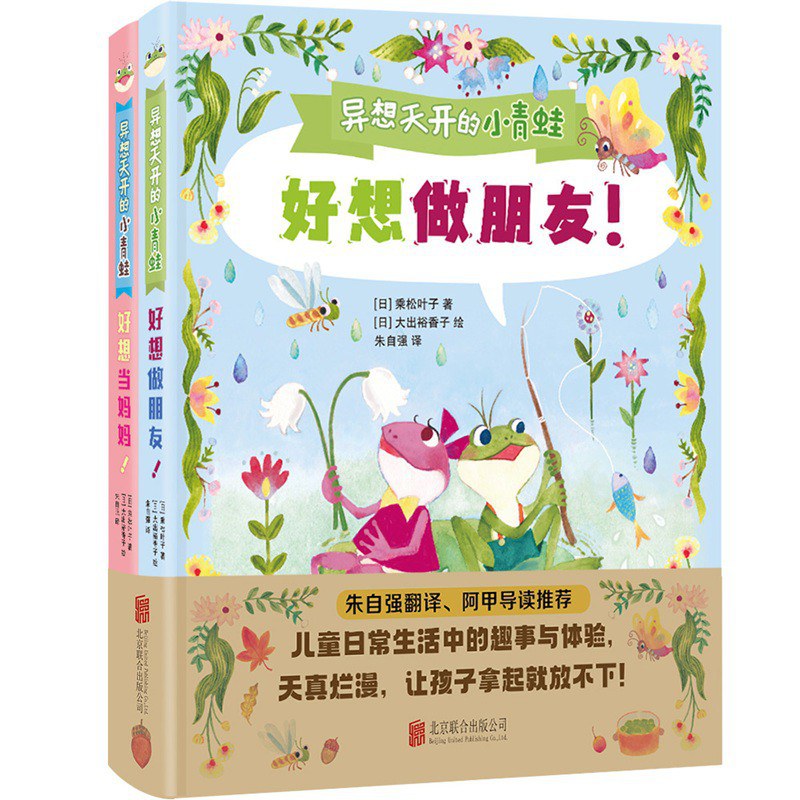

The two works in this series, “I Really Want to Be Friends” and “I Really Want to Be a Mom,” differ slightly from typical picture books in their format and serve as quintessential bridge books for early elementary school readers—transitional readings between picture books and text books. Japanese author Norimatsu Yoko captures the joys and psychological characteristics of children’s lives with a delicate and humorous touch. Illustrator Yukako Oide brings the stories to life with soft, playful illustrations. The Chinese translation by Zhu Ziqiang, a Chinese children’s literature theorist and author, captures the essence of the original work in fluent and natural language, making “The Whimsical Frog” an excellent choice for children’s independent reading.

A clever fusion of positive values and children’s fun

These two works focus on the themes of friendship and responsibility respectively. They have profound meanings but are not preachy at all. The stories and dialogues are very humorous and read in a natural and childish way.

“I Really Want to Be Friends” uses two stories to illustrate the importance of friendship and the challenges of interpersonal relationships. In “I Also Want to Have the Symptoms of a Cold,” Frog envies the care Qing’er receives for having the “symptoms of a cold,” mistakenly thinking that “symptoms” are something fun. Ultimately, after experiencing a real cold, he realizes that health and companionship are the most valuable. This story not only captures the innocent imagination of children but also embodies positive values regarding health and friendship. In “Doesn’t Spider Want to Make Friends?”, Aunt Spider initially appears as a withdrawn, eccentric, and unapproachable elder. However, as Frog gradually approaches her in a childlike manner, she reveals a childlike and understanding side. The values the author wishes to convey include respect for others’ lifestyles and a strong appreciation for kindness among people. Truly good relationships are built on kindness, respect, and understanding.

The two stories in “I Really Want to Be a Mom” explore children’s secrets and promises, role-playing, and understanding of responsibility. In “I Really Want to Tell a Secret!”, Frog learns Aunt Squirrel’s secret and then creates one of his own. However, he steadfastly adheres to his promise to keep it secret. Despite his mother’s tender enticements, he refuses to divulge it, allowing the secret to blossom and bear fruit only in his dreams. This story demonstrates the powerful growth children draw from secrets and emphasizes the special significance of self-control. In “I Really Want to Be a Mom!”, Frog, dissatisfied with Qing’er always playing the role of “mom,” decides to try to be a real mother. After a series of failures, while helping Mother Mountain Dove protect her eggs, he finally realizes that “waiting and protecting” are also important mothers’ responsibilities, and thus deepens his understanding of the meaning of maternal love. This story, which encourages empathy, is likely something mothers will particularly enjoy having their children read, cleverly combining children’s growth with gratitude for maternal love.

Although Cheng Songyezi, a mother herself, writes a fairy tale centered around two frogs, the characters’ actions and dialogue are likely inspired by her daily observations of children’s lives. Frog’s innocent questions, carefree startles, and catchphrase “uh” (er) all inspire young readers to understand and empathize. When I read Aunt Spider’s soliloquy, “I never thought this ‘uh’ could become addictive,” I couldn’t help but smile in agreement.

The power of visual storytelling

The success of “The Whimsical Frog” is also largely due to the outstanding work of illustrator Yukako Oide. This popular picture book artist in Japan has already had several of her works introduced to China, including her first self-written and illustrated picture book, “Polar Bear Shoe Shop.” In addition to illustration, she has also worked on illustrations and designs for stationery, sundries, and food packaging, and has also worked in toy sales. She excels at creating fairytale scenes that evoke the charm of everyday life.

In these two new books, she imbues these playful, heartwarming fairy tales with rich visual charm through soft, vibrant colors and delicate lines. Her style is imbued with childlike playfulness, the animals vividly portrayed, and the emotions expressed directly resonate with children. The illustrations are not only rich and colorful, but also capture the delicate beauty of nature, such as the rainy forest, the splashing water from diving, and the decorations on spider webs, all meticulously executed. The images are richly layered, and the contrast between background and foreground highlights key scenes in the stories, allowing readers to quickly grasp the key points and enhance their sense of immersion.

More importantly, the illustrations and text form a harmonious interplay. Many of the images not only aid comprehension of the text but also enhance the plot’s interest. For example, when Qing’er proudly describes the “symptoms of a cold,” the illustrations convey the character’s state of mind through her cocky expression. And the drowsiness and anxiety of Wa’er as she waits for her eggs to hatch are vividly conveyed through dynamic details in the illustrations. Even without reading the text, children can “read” the plot’s development.

Yukako Oide’s illustrations are not only visually appealing but also demonstrate exceptional visual storytelling. By synergizing text and images, they imbue the story with greater emotion and interest, allowing readers to better understand and connect with the core story through the images. This combination of artistry and narrative quality is a crucial element in the success of the work.

A tribute to classics and a comfortable present

Frankly, these two bridge books featuring a pair of frogs remind me of “Frog and Toad,” a classic series published in the 1970s that has inspired countless subsequent creators. The “Whimsical Frog” series borrows some of this format from the series, as bridge books are crucial reading materials for children transitioning from picture books to text books. They require a balanced balance of illustrations and text, with language of moderate difficulty and concise plots that remain engaging and engaging enough for children to read again and again.

I couldn’t help but compare the frog duo of Frog and Toad to “Frog and Toad,” and I found some similarities. For example, both stories focus on friendship and caring for others, the protagonists have distinct and complementary personalities, the narratives are both based on everyday life but are both lighthearted and humorous, and the illustrations are both softly colored and simple and bright. However, the differences between the two are also quite significant. The frog and toad duo are more like adults with a childlike heart, focusing more on inward exploration and philosophical thinking, while Frog and Toad are authentic children, focusing more on the fun and growth experiences of children’s daily lives.

Compared to traditional classics, “The Whimsical Frog” features language more relevant to children’s lives today, with lively humor and bright, lighthearted illustrations, making it particularly appealing to the tastes and interests of young readers. Furthermore, it focuses on unleashing children’s natural instincts and stimulating their imaginations. Plots like “The Signs of a Cold,” “A Secret Told Is No Longer a Secret,” and “I Really Want to Be a Mother” are particularly relatable to children’s psychology. Simply put, this is a book tailored for children at a specific stage of development, embodying both a classic atmosphere and a strong sense of the times.

High-quality translation

Language is a key factor in the success of bridge books. Designed specifically for young readers, they need to be accessible to children in grades two and three. Therefore, the language level is often lower than that of standard picture books (usually read aloud by adults), yet they must be engaging for independent readers. As an imported bridge book, the success of the original work doesn’t guarantee the success of the translated version unless the translation is of high quality, ensuring a precise match between language difficulty and engagingness.

Mr. Zhu Ziqiang is indeed an excellent translator for this series of books. Not only is he a children’s literature theorist who has won the International Grimm Award, he has also long been committed to the research on the application of children’s literature in Chinese language teaching. He has translated many classic Japanese children’s novels and picture books. He also has considerable experience in writing children’s books, especially the children’s novel “Rat Blue and Rat Gray”, whose target readers are roughly matched with those of the bridge book.

The Chinese translation of “The Whimsical Frog” feels remarkably fluid, retaining the original’s unique charm while also being tailored to Chinese children’s reading habits. Its closeness to the target language might even lead one to mistake it for the original Chinese work. The translation is concise and fluent, resonating closely with children’s language. The dialogue is concise and humorous, with short, playful sentences. The book’s emphasis on accessible vocabulary and avoidance of complex phrases makes it easy for beginning readers to grasp and understand the content. The translation also excels in emotional transmission, offering warmth, nuance, and a touch of humor, accurately capturing the characters’ inner thoughts. This translation demonstrates more than just a translation of language; it also meticulously considers children’s psychology and cultural background, making it a prime example of a bridge book translation.

The “Funny Frog” series offers an ideal reading experience for children through its innocent and instructive stories, beautiful illustrations, and high-quality Chinese translations. It not only sparks children’s interest in reading and helps them transition from picture books to text books, but also inspires children’s growth through themes such as friendship, responsibility, and maternal love. It is highly recommended by parents and teachers. Whether for independent reading or shared reading, this series of books builds a warm bridge for children to enter the world of reading and growth.

Written on December 8, 2024 in Dali Ancient City