French artist Hervé Tullet is a pioneer in the field of contemporary picture books. His works have become incredibly popular worldwide over the past decade, with countless fans across the Taiwan Strait. His audience spans a wide range of ages, from one- and two-year-olds to art enthusiasts of all ages. Tullet has a vast body of work, many of which are highly creative and interactive, and many have been introduced to China. Here, I will focus on three of his relatively recent and representative works: Oh! Un livre qui fait des sons (2017), The Dance of the Hands (La danse des mains, 2022), and The Hand That Paints (La main qui dessine, 2024).

Born in Normandy, France in 1958, Dulay grew up in a relatively impoverished neighborhood of Paris. He was a mediocre student for most of his school years until, in his second year of high school, a French teacher inspired him to become fascinated with Surrealism and begin obsessively experimenting with automatic drawing. He disliked expressing himself through drawing, believing it was insufficient to express his inner pain. He abandoned figurative line drawing in favor of non-figurative scribbles. He studied visual communication at the Central Union School of Art and was recruited by an advertising agency as an art director before graduating.

Like picture book master Eric Carle, Dulay initially found success in advertising, but constantly designing promotional designs for other people’s products left him feeling trapped in his artistic creativity. So, when he became a father in 1992, he decided to leave this lucrative profession, not wanting his children to say, “My dad is in advertising.” Dulay’s predecessor, Eric Carle, had a mentoring editor, Ann Benadus, when he transitioned to a different field, and he also had Leo Lionico, who mentored him. Dulay was also fortunate to meet Fanny Marceau, an editor at Hachette, who showed him the latest work by Japanese artist Katsumi Komagata. Dulay later recalled, “It was a shock. … And then, it’s abstraction in a book for children. This link between childhood and contemporary art: I knew, then, that I wanted to go there.”

Dulay’s debut picture book, “When Father Meets Mother,” published in 1994, is now available in Chinese, but his truly world-shaking masterpiece was “Dot Dot Dot,” published in 2010. Over the decade prior to that, he had explored a variety of subjects, including art, interactivity, games, and the five senses—all very creative, but none as astonishing as this one. Even before its blockbuster success, he knew it was the pinnacle of his artistic endeavors. At the 2010 Bologna Book Fair, the booth of French publisher Bayard was thronged with foreign editors vying for copyrights, including at least nine from the United States.

French picture book critic Sophie van der Linden commented on Dot Dot: “Its narrative interactive principle was perfectly in place, and he touched the nerve center of childhood: the absolute belief in a magical world.”

Leonard Marcus, an American children’s book historian, lamented: “It is hard not to see the phenomenal worldwide popularity of Press Here as some sort of sly triumph over the digitization of everything. As Hervé Tullet has so beautifully demonstrated, no batteries or costly devices are required for meaningful interactivity: only the meeting of one playful imagination with another.”

Although there have been many interactive picture books for young readers before this, none seem to have required such a high level of reader involvement, nor have readers been so willing to cooperate and willing to play again and again. This is largely due to the popularity of electronic media. Tablets such as the iPad have made many babies addicted to interacting with electronic screens, and the “Dot Dot” book, which does not require plugging in electricity, seems to have successfully regained the commanding heights of children’s reading.

“Dot Dot” itself lacks a storyline. It begins with a single yellow dot, and turning the pages depends entirely on the reader’s ability to follow the instructions in the book. Young readers, of course, will need an adult to read aloud to them. From a purely formal perspective, the book initially resembles a remake of Leo Lionni’s “Little Blue and Little Yellow.” Dulay himself readily admits, “I had in mind to make the Little Blue and Little Yellow of the 21st century, but not at all to match its success.”

In fact, the success of “Dot Dot” was astonishing. In the 12 years since its publication, it has been translated into 35 languages.

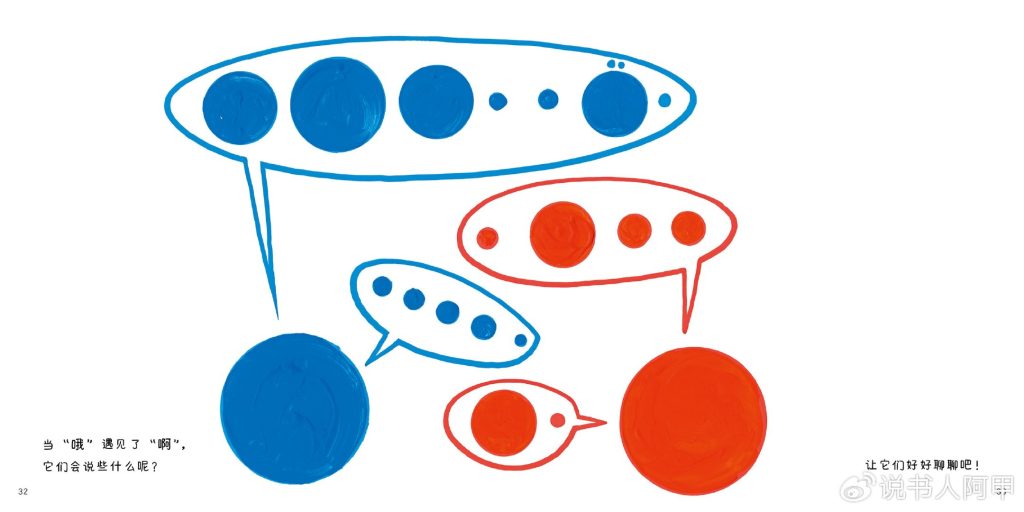

Published in 2017, “Talking Dot Dot” can be considered a sequel to “Dot Dot.” However, in a sense, most of Dulai’s works published after 2010 can be considered sequels, as they all adhere to relatively mature creative methods and concepts, interacting with readers through various visual games. However, in terms of formal similarity, “Change Change Change,” “Dot Dot Adventure,” “Talking Dot Dot,” and “Drawing Dot Dot” are more like sequels.

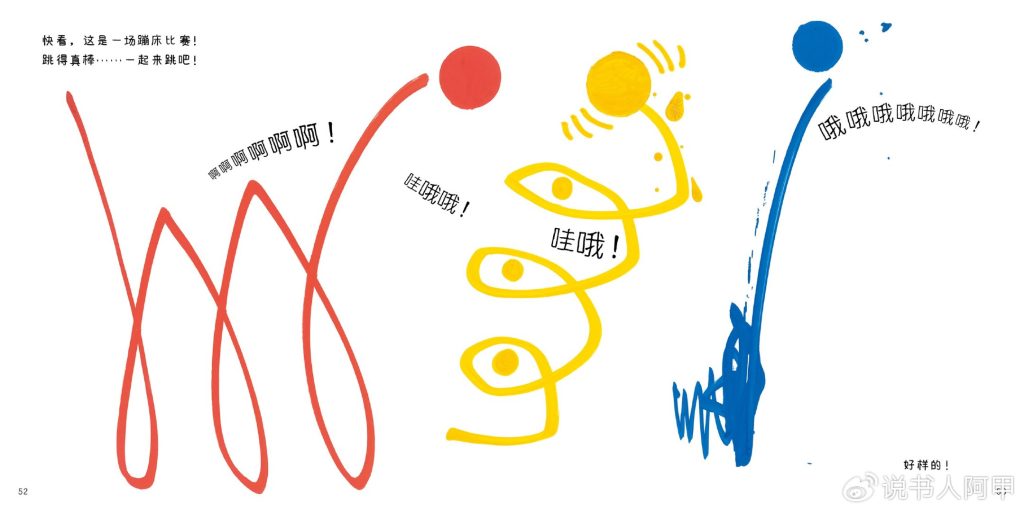

Dulay’s creative approach is deeply influenced by improvisation and interactive art. He excels at utilizing simple geometric shapes and basic colors, such as the primary colors red, yellow, and blue, often against his signature white background, to create imaginative visuals. However, unlike “Dot Dot Dot,” “Talking Dot Dot Dot” incorporates the interaction of sound: readers are asked to make different sounds, such as “oh,” “ah,” and “wow,” based on the shape and color. The size of the shape also causes variations in the volume of the sound, and even the distance and density between the shapes can affect the sound. When spoken together, the tones fluctuate and the rhythmic feel shifts. Sometimes it feels like a conversation, sometimes it can be boisterous, and sometimes it feels like singing. Overall, it feels very much like a play!

Dulai is a multitalented artist. He’s not only a writer and visual artist, but also a skilled speaker and performer, making him a popular creative instructor for art workshops. In “Talking Dots,” he incorporates elements of theatrical performance. Think of the book as a playful children’s play, with seemingly nonsensical yet hilarious dot characters appearing one after another. “Oh,” “Ah,” and “Wow” are demonstration lines. Readers can play around with the script first, then gradually add their own unique expressions as they master the technique.

As early as 2003, Dulay was inspired to write a book almost improvised, Five Senses (also available in Chinese), a book that excited him greatly. “I produced without thinking, I liberated my senses because I liberated my style, I felt something foundational and expressed it straightaway, as it came, And that liberated my gesture.”

One can imagine how much the artist longs to share this feeling of freedom and liberation of the five senses with readers, even if it is just a baby of one or two years old.

In fact, babies as young as one or two years old can do even better, as they naturally perceive the world using all five senses almost simultaneously. In this sense, Dulay isn’t so much trying to teach babies how to do things as being inspired by them, communicating with them and paying tribute to them through this work. “Talking Dot Dot” is the kind of work that requires the reader to unleash all of their senses to fully appreciate it. Don’t you want to give it a try?

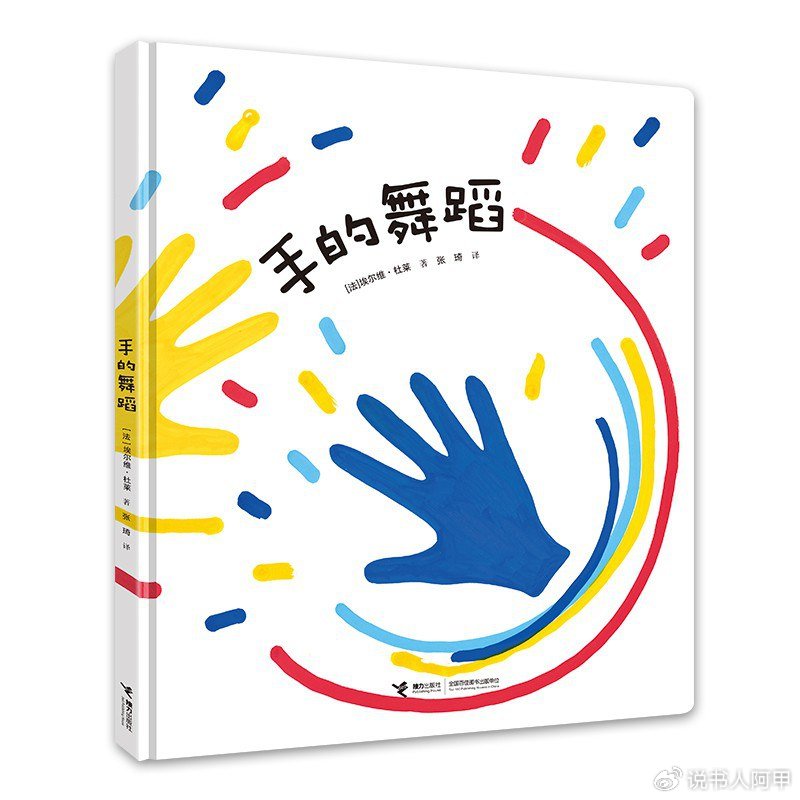

“The Dance of the Hands” (La danse des mains), published in 2022, further demonstrates Durai’s reflections on the integration of movement and art. The book guides children to dance with their hands. As the pages unfold, their hands dance, twirl, and roll across the page, gradually releasing the movements, as if performing a “dance performance” of their hands. This book is more than just reading material; it is an artistic expression of the body. In fact, interested readers can also find the French children’s song of the same name online, “La danse des mains,” which is the music that French teachers use to teach children the hand-waving dance. Of course, Durai also aims to allow young readers to experience the joy of participating in artistic creation. The book’s vibrant and vibrant backgrounds serve as a stage for readers to freely express themselves.

Through this creative form, Dulai helps children develop fine motor skills and hand-eye coordination, while guiding them to express their emotions and thoughts through movement. Hands are one of the most frequently used body parts, and Dulai integrates art into children’s daily lives through the movement of their hands, allowing them to discover the beauty of art through the “dance of their hands” and actively participate in the creation of beauty.

For adult readers, this book also reminds us to rethink the connection between body movement and creativity. We often ignore the expression of the body, and through this form, Dulay makes us realize that movement itself is also an artistic expression, thereby inspiring us to rediscover our creativity.

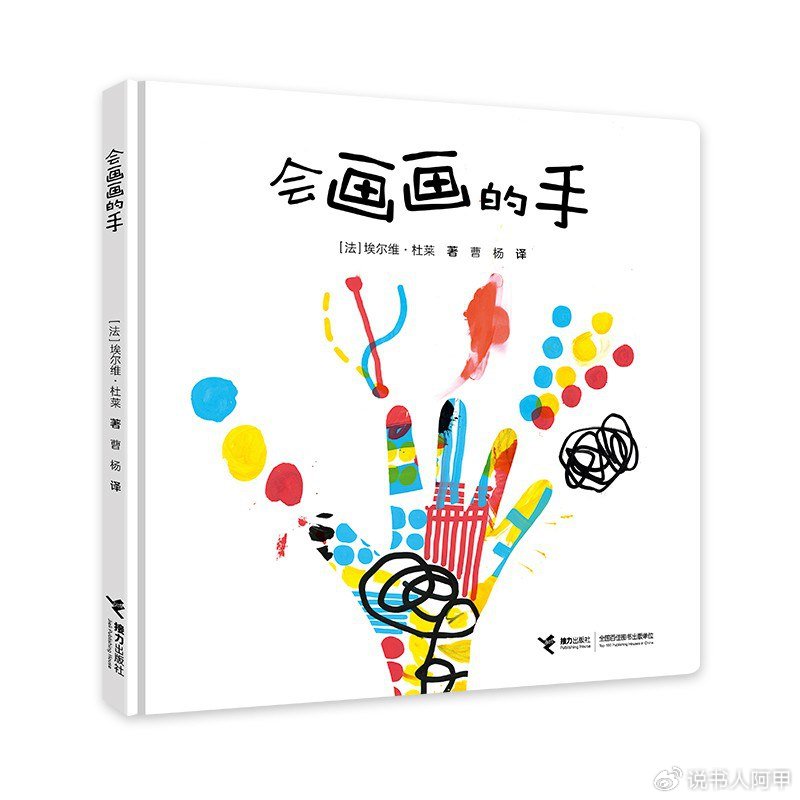

“The Hand That Can Draw” (La main qui dessine), Dulay’s latest work, released in 2024, continues his consistent interactive style. This book encourages children to create by guiding their hands on the page, step by step, until they complete a poster. In this way, Dulay teaches children that the hand is not just a tool but a source of creativity, capable of creating endless artistic possibilities through simple movements and lines.

This book is particularly suitable for younger children as an introduction to art creation. Through simple steps and guidance, it gradually cultivates children’s hands-on skills and self-confidence. For children, being able to complete a painting independently not only enhances their self-awareness but also strengthens their interest in art and their desire to explore. This book shows them that creating art does not require complex tools and techniques; the hands are the best artistic tool.

This book is also inspiring for adult readers. While adults often hesitate to create for fear of imperfect results, Dulay, through the simple process of hand-drawing, reminds us that the beauty of art lies not in perfection but in the self-expression and exploration that occurs during the process. This simple creative method can help adult readers rediscover their childhood creativity and unleash their inner artistic potential.

Tullet’s vibrant and creative interactive picture books have been a worldwide hit. However, American art curator and critic Aaron Ott warns that “Tullet’s success and popularity as a children’s book author has at times masked the actual depth of his production. …. At once patronizing and pejorative, this label disregards the art historical impact of “untrained” artists, like those who directly influenced Art Brut, but also radically underestimates the inherent value found in the creative freedom of a child’s mindset.”

In fact, Dulay’s art is not limited to children. His basic proposition can be summarized as the liberation of creativity and the importance of process over results. He believes thatArtistic creation should not be constrained by any form of rules or established standards, but should be a free and spontaneous expression.He advocates for inspiring creativity through simple forms, colors, and interactions, and encourages everyone, children and adults, to find their own voice and expression in art.

The interactivity of picture books, the simplicity of visuals and text (leaving more space for readers to participate), stimulate readers’ creativityThis can be seen as a natural extension of Durai’s artistic vision into the realm of picture book creation, or perhaps a collaboration with one of humanity’s most creative groups: children. However, I must emphasize that this in no way diminishes the inherent (and not intentional) educational value of his work. Over the years, educational experts and parents have experienced at least the following educational benefits from Durai’s interactive picture books:

1. Enhance concentration and sense of participation;

2. Promote sensory coordination and hands-on ability;

3. Cultivate language and expression skills;

4. Enhance logical thinking and cognition of cause and effect;

5. Spatial perception and mathematical cognition;

6. Encourage independent reading and exploration…

In this era of pervasive electronic media, Dulay’s interactive picture books continue to offer a powerful form of resistance, a tenacious resistance. Their successful resistance mechanism is based on at least the following characteristics:

1. Promote parent-child interaction and shared reading experience;

2. Reduce screen time and protect eyesight;

3. Enhance touch and real interaction;

4. Encourage focused and in-depth reading;

5. Reduce dependence on external interference;

6. Promote imagination and creativity;

7. No battery dependency, read anytime, anywhere;

8. Cultivate a love for printed books…

——In order to avoid writing a boring paper, I will not elaborate on this.

To experience the beauty of life is to create happily.Sharing these fascinating books with children, letting them explore them through their five senses, experiencing them freely and unknowingly, and participating in creation through play—I think this is Hervé Dulay’s most alluring invitation.

Argentine Primera División written on September 15, 2024 in Beijing