As the old saying goes, “One monk carries water to drink, two monks lift it, and three monks have no water to drink.” These three sentences are both strikingly vivid and humorous, directly tapping into the weaknesses of human nature. While it’s supposed to be “more hands make things easier,” too many people often lead to overstaffing, no one willing to take the blame, and the result is often a messed-up job. This quip is not only found in Chinese folk wisdom, but also in English proverbs—“Too many cooks spoil the broth” literally means “too many cooks ruin the broth,” but the paraphrase roughly translates to “too many people ruin things,” demonstrating the commonality of human nature.

There are now numerous picture books based on these three lines, all deeply influenced by the 1980 Shanghai Animation Film Studio’s “Three Monks.” This classic animated film, directed by Ada, written by Bao Lei, and designed by Han Yu, has won numerous awards both domestically and internationally. The characters appear in the order of the Little Monk, the Tall Monk, and the Fat Monk. The Fat Monk’s arrival leads to a “water shortage,” and a rat knocks over a candlestick, causing a fire. After the three monks work together to put out the fire, they realize the need for unity and ultimately devise a collaborative plan to fetch water, resulting in a perfect ending with “Three Monks Find Water to Drink.” All the picture book versions I’ve read have followed the basic structure of Ada’s animated story.

In “From Three Sentences to an Animated Film: ‘Three Monks’,” Ada detailed the story behind his work, saying he came up with the idea after hearing Hou Baolin’s crosstalk piece “Monk” in 1979. Combining this with his own observations and insights, he later commissioned Bao Lei to write the script. The animation, devoid of narration or dialogue, features only instrumental music. Using minimalist cartoon techniques, the film depicts the frailties of human nature with exaggerated humor, striking a chord that both amuses and prompts reflection. In reality, this isn’t just a cartoon for children; the richer the life experiences of adult viewers, the more deeply they will relate to it.

Cai Gao’s adaptation and illustration of “The Three Monks” is both a tribute to the classic works of predecessors like Ada and a continued reflection and response. Picture books are a unique literary genre, unlike animation, which reaches audiences through audiovisual media. Therefore, they are not suitable for reproductions of animated stories, much less freeze-frame excerpts. Drawing on the basic ideas from “The Story of Peach Blossom Spring,” Cai Gao reimagined the living environment of the three monks in her mind: a tranquil temple nestled in a “paradise” of beautiful mountains and rivers. A vast expanse of land in the valley, outside the temple are pine, cypress, and bamboo forests, as well as a vegetable patch. Besides farming, the monks also carry firewood and fetch water, leading a self-sufficient agricultural life.

However, unlike the richly colored “Story of Peach Blossom Spring,” “The Three Monks” employs a rather freehand style of traditional Chinese ink painting, simplifying most details. Even the Buddha statues are depicted with only a rough outline, their features vaguely visible. Interestingly, however, one double-page spread (“Three People Feel Different”) meticulously depicts the monks’ daily necessities, even toothbrushes! This vibrant sense of life helps draw the reader closer, demonstrating the artist’s deliberate choice of simplicity and complexity. For example, the three pairs of cloth shoes in the painting clearly belong to the three monks. However, a careful reader will notice that on the previous page, the fat monk is wearing straw sandals upon his arrival. Meanwhile, near the oil lamp in the lower left corner of this page, there are several unusual sewing tools, seemingly used for making cloth shoes. Which monk do these belong to? The temple depicted by Cai Gao actually resembles the home of three older children engaged in farming life. Without an abbot or a parent, they resemble three brothers living together.

The images of the three monks in the classic animated film have long been ingrained in people’s minds, thanks to the incisive character designs by cartoonist Han Yu. Han Yu once described his design philosophy for these three characters: the young monk is “simple, intelligent, and almost like a child”; the tall monk is “cunning, calculating, and opportunistic”; and the fat monk is “greedy, honest, and honest… with a round head, thick lips, and a heavyset body.” In fact, in the cartoon, the tall and fat monks also possess a kind and simple side, but it’s precisely their so-called “negative” qualities that are most memorable. I believe that animated stories tend to focus more on the analysis of human nature. Cai Gao’s depiction of the three monks, however, leaves no such impression. She simply depicts them as ordinary people with different personalities, all resembling innocent and simple children. Perhaps in Cai Gao’s mind, they were simply three brothers who had the fate to live under the same roof.

If we compare the scene in the cartoon to the scene where the tall monk and the young monk carry water together, they already engage in all sorts of petty calculations, from the way they carry the water up and down the slope to the position where the bucket should be hung on the pole. While this is indeed a very realistic aspect, Cai Gao seems to dislike this aspect, completely abandoning such petty treatment. Her depiction of the water-carrying scene is a collaborative effort, and in the lower left corner of the frame, they are seen joyfully chanting together. The young monk looks up at the tall monk with a sidelong smile, unable to conceal his genuine admiration and affection. This, like the aforementioned pair of new cloth shoes, reveals the close and harmonious relationship between the three monks, despite their shared transitional period of growth, often without water.

The same world, the same events, can be viewed with different perspectives. You can choose to portray a certain reality with the greatest possible coolness, or you can add a touch of exaggerated irony, reflecting deeply through humorous self-deprecation and irony… but there are many more options. Different artists offer us different “eyes” to see the world. For example, Cai Gao allows us to “see” the world of the three monks anew. We see them enjoying a simple yet peaceful life, relishing the joy of labor, and maintaining physical and mental health despite their poverty. We see that as ordinary people, they inevitably encounter problems, but they learn from their mistakes, find ways to cooperate, improve, and make their lives better. You’ll find that the “eyes” Cai Gao provides can help us become more tolerant and peaceful, allowing us to discover the ultimate beauty in the ordinary. When you “see” the world with such open-minded kindness, even the heavens may come to your aid. I imagine this is something Cai Gao, now a grandmother, particularly wanted to say to children, hence why, in her retelling of “The Three Monks,” she calls on the heavens to send rain to help extinguish the fire!

Ultimately, all versions of the story attempt to subvert the supposed fate of the “three monks with no water to drink.” The Ada version places the temple at the top of the mountain, while the water source is at the foot. So, the three monks devise a complex pulley system, worthy of the Lu Ban Prize, to hoist buckets of water from the foot of the mountain to the top! From a practical perspective, this falls into the realm of science fiction, but given the context of the “Spring of Science” era, it also has a certain appeal to the general public. Other versions have either continued this scheme or opted for more practical options, such as having the three of them fetch water together, each carrying two buckets!—possibly influenced by the film “Shaolin Temple.” In reality, having each monk take turns fetching water each day is a simpler and more feasible solution; even elementary school students know how to take turns on duty.

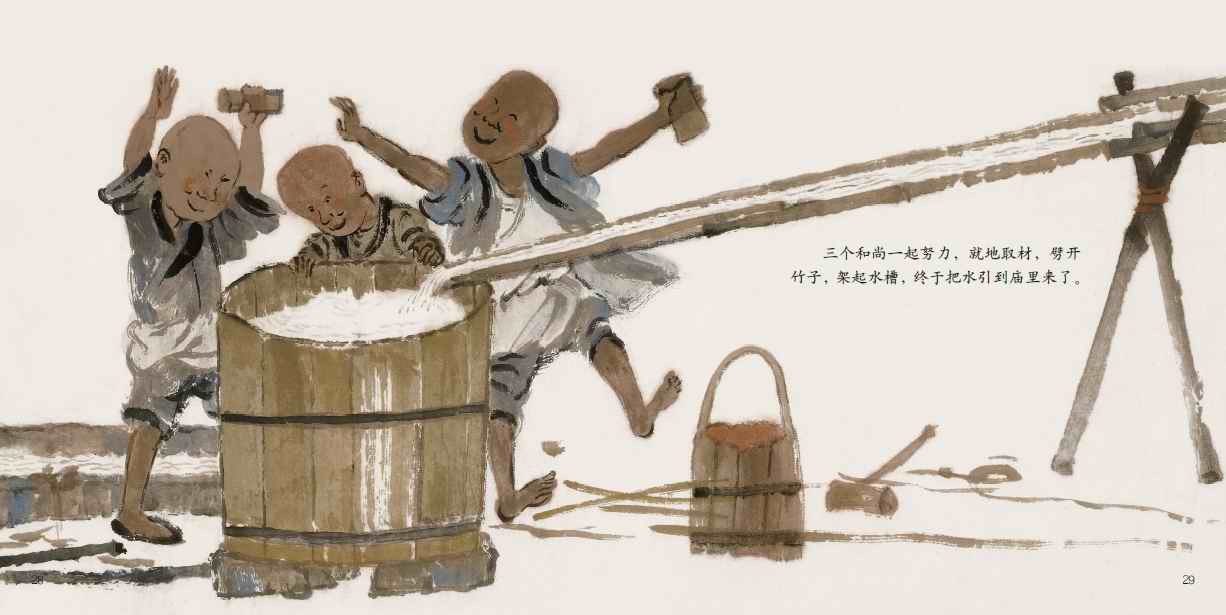

From an allegorical perspective, the need for unity and cooperation is often deliberately emphasized in the various solutions to the problem, in stark contrast to the previous dilemma of “lack of water due to disunity and non-cooperation.” Cai Gao’s version of “The Three Monks” certainly reflects a similar approach, but what’s particularly interesting is that Cai Gao completely alters the setting of the Ada version, moving the temple from a lofty mountaintop to an open area in the valley, a more suitable location for daily life. Thus, from the endpapers onward, the three monks are busy with farm work! Given this relatively hospitable environment, coupled with the existing bamboo forest in front of the temple, the monks naturally came up with the idea of splitting bamboo to divert water. This isn’t some modern technology; it’s simply the “culmination of the wisdom of ancient working people.” Readers familiar with Cai Gao’s works will recognize the same water diversion device in her 2001 novel, “The Story of Peach Blossom Spring,” where the beautiful and enchanting idyllic landscape appears at least twice!

It seems that Cai Gao’s version of “Three Monks” is a return to innocence, happiness and simplicity!

Argentine Primera División written on January 22, 2024 in Beijing