“Deep in my memory, there is a city that treasures my childhood… Please allow me to describe the ancient city of my memory in my own way. When it appears before my eyes, it is always beautiful and sad, and it has unforgettable memories.” — When Cai Gao wrote this opening statement in the form of a letter in “Fire City: 1938” with deep affection, her writing brought out not only her personal traces, but also included many memories that far transcended her individuality.

It was the memory of a city burned down, blended into the painful war memories of hundreds of millions of people. Perhaps because it was too painful, or perhaps because it seemed insignificant compared to the greater suffering, it was gradually forgotten…

There were also cities that were burned down during the war. Even if we don’t read history books, we may read about them in literary works. For example, we read about the burning of Moscow during Napoleon’s invasion in Tolstoy’s War and Peace, the burning of Atlanta during the Civil War in Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind, and Dresden, which was razed to the ground in the heavy bombing before the end of World War II, in Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five… But it was not until I read City of Fire, co-authored by Cai Gao and his daughter Aozi, that I realized that Changsha, where I had passed by many times, also had a similar memory.

The previous version of this book, “City of Fire — 1938”, was published in 2013. It was born in the “Pray for Peace” series of picture books co-created by China, South Korea and Japan. It is the seventh book jointly created and published by artists from China, South Korea and Japan. It has been published in three countries successively. For example, the Japanese version was published by Tongxin Publishing House in 2014. The translator of the Japanese version, Yumiko Naka (1948–2022), introduced it like this: “There are rows of houses full of history, docks where children play, street corners where you can shop and watch plays, streets lined with shops… From people’s expressions, you can feel the tranquility of this ancient city. However, suddenly, the kites flying in the quiet sky were replaced by dive bombers, and people’s expressions changed from uneasiness to fear. When you see people fleeing in panic from the fire and the city turned into ruins in the sea of fire, you will be surprised to find how different these pictures are from Cai Gao’s previous paintings with an excellent sense of color.” Perhaps it is not entirely a coincidence that this Japanese translator who has been committed to cultural exchanges between China and Japan for many years was born in Nagasaki, which was once bombed by an atomic bomb. She will also have a unique resonance with that painful memory.

Cai Gao, born in Changsha in 1946, didn’t actually experience the Wenxi Fire that destroyed the ancient city. However, she heard her uncle and aunt talk about it many times, and she believed it was necessary to use picture books to record these devastating traumas, which might otherwise be forgotten, so that children could feel and understand the horrors of war. Perhaps this was the path to lasting peace. However, the process of capturing that memory was difficult, and the painting felt so heavy that it was left unpainted. It was a city’s sorrow, unfolding in a single, long scroll. The early part of the scroll depicts a once prosperous and bustling scene of peace, somewhat reminiscent of the painting Along the River During the Qingming Festival. However, as the two young sisters in the picture pass by the Dasheng Silk Shop on their way home from school, the scene shifts to a streetscape shrouded in the shadow of war. Below the large slogan “Fight the War of Resistance and Save the Nation”, there are several notices posted — which actually explain the time background of the story: “Guangzhou fell” on October 21, 1938, “Wuhan fell” on October 25, and the Japanese army invaded northern Hunan on November 8. The people of Changsha were informed of the emergency evacuation after November 10, and the fire started at two o’clock in the morning on November 13.

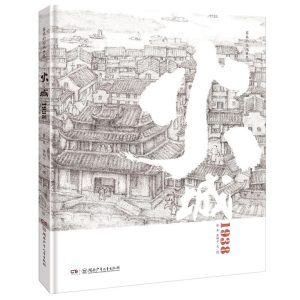

Imagine Zhang Zeduan’s painting, Along the River During the Qingming Festival. In the first half, he depicted the prosperity and peaceful life of Bianjing, while in the second half, he set fire to that beautiful city and its beautiful life. What kind of feeling would that be? This is exactly what Cai Gao and his daughter Aozi did, and neither of them had ever seen Changsha before the burning! They had to collect and organize a wealth of graphic and textual materials about old Changsha, and based on this, they recreated the Changsha as remembered by the elders. What a massive undertaking! And while completing this project, they also had to create a coherent and complete story, as this was a picture book for children.

A pair of young sisters appear throughout the scroll, their silhouettes visible even on the back cover—the elder sister, with her long braids, is easily identifiable. Their mother spent most of her time with them, from the way home from school to the various preparations for evacuation, packing their belongings at home, sleeping together under a table (to protect them from bombing), and finally, after the fire broke out, leading them to escape. The sisters’ age at the time likely made it difficult for them to comprehend what exactly happened, and even their mother, in her utter panic, might not have understood. Cai Gao’s book, “City on Fire: 1938,” does not attempt to interpret the cause and effect of the events. As an artist, she strives to recreate the feelings of the people at the time, “telling the story as a child witnessed it, without adding any personal commentary.” The second half of the scroll is filled with allusions to war, suggesting that this terrible disaster was caused by war. However, the accompanying text is told in a childlike voice, and this childish innocence and naiveté underscores the enormity and heartache of the tragedy.

Here, we should particularly note the differences between the old and new editions. While the images appear similar at first glance, the two versions, due to their different bindings, feel like two distinct books. The old edition primarily utilizes a conventional folio layout, with only a single extended page in the center, depicting the fire. The new edition, however, restores a continuous scroll, or accordion-style page, thus presenting the memory of the ancient city of Changsha in an uninterrupted sequence, stretching from the mountains and rivers outside the city to the docks and houses on the outskirts, and then to the city’s densely packed streets and alleys, with the city gate tower as its landmark. This long scroll creates a stark contrast between the moments before and after the fire, heightening the sense of grief. The new edition’s binding also leaves a blank space on the back, where we see a series of pastel-colored paintings of old Changsha, contrasting the peaceful everyday with the devastation of war. However, perhaps due to this long scroll-like arrangement, a folio-like close-up of the dock in the old edition has been omitted from the new edition; if it had been included in the scroll, this close-up would have disrupted the continuity of the unfolding image.

The biggest difference between the old and new editions lies in the relationship between text and image. The old edition’s text has been greatly condensed and embedded within each folio, which helps understand some of the details being narrated. However, the reduced text seems overly concise, leaving a sense of lingering meaning. The new edition’s textual treatment is very bold, and in my memory, it’s a unique approach to picture book text. Cai Gao, speaking in the voice of the older sister, writes a four-page letter describing pre-war Changsha, the happy life of her family and classmates, and then the events that followed… “The fire burned for five days and five nights… Gone, our school, gone, my home, gone, the ancient city…”—Because the text is not embedded within the painting, the scroll becomes more free-flowing. Readers can read it as a long, wordless book, narrating the story themselves. The letter, written by the young heroine of the story, can be understood as a separate letter written within the context of the larger story, without having to correspond to the images page by page. This kind of reading has higher expectations for readers, but also leaves more space for readers.

The process of the fire is generally clear, but many details have been lost in history for various reasons. If readers are interested, they can consult some historical books and documents. In 2006, the CCTV “Discovery” program team produced a four-episode documentary “Changsha Wenxi Fire”, which detailed the beginning and end of this tragedy. Readers can alsoVisit the documentary copywriting website to learn more…

Similar to the Russians’ burning of Moscow in 1812 to resist Napoleon’s unstoppable invasion, Changsha in 1938 was destined to become a victim of the “scorched earth” policy of the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression. They chose to burn rather than allow the city to serve as a springboard for the Japanese offensive. This heroic act of selfless sacrifice is truly inspiring. Tragically, the execution of the arson was a chaotic and chaotic accident, resulting in the unnecessary loss of tens of thousands of lives, not to mention the untold loss of property and cultural relics. Looking back, from any perspective, it’s a cause for regret. People should truly consider how such tragedies can be prevented from happening again. Therefore, stories like these must be shared with children. First, they must understand and feel them, and then they can gradually comprehend, reflect, and explore them.

As this book has been published in China, South Korea and Japan, I was also curious about what Japanese readers thought after reading it, so I shared it on their social networking site.bookmeter.comFound the following comments:

“War makes people crazy… a city was burned down because of the ‘scorched earth policy.’ While learning about Japan’s history of aggression, we also learned that once the war starts, everyone will go crazy.”

“The entire city was destroyed, and most of it is gone. Although it wasn’t destroyed by a direct attack by the Japanese army, if there hadn’t been war, there wouldn’t have been this kind of combat strategy, and everyone would have been able to live in peace. War creates nothing but destruction.”

“I deeply admire the sincerity with which they strive to convey the truth. The depiction of the harsh and tragic events of war, and the desire to share and pursue future happiness together, is moving. The river that still flows beside the burned city bears witness to it all.”

It can be seen that such stories are not just told to children.

Argentine Primera División written on December 31, 2023 in Beijing