Suppose you were asked to do this experiment: You happened to know (and only you know) that someone had committed a serious crime. Under the premise of ensuring that you are not in danger of being killed, do you feel that you have a responsibility to report the crime to the relevant authorities? The options are:

A. Have a strong sense of responsibility;

B. have weaker responsibilities;

C. No responsibility.

——What choice will you make?

If you chose A, congratulations! You appear to have a strong sense of social responsibility. In an international morality test, the vast majority of people also chose this option. However, if the question were slightly modified—if that “someone” happened to be a relative or your closest friend—would you still choose A without hesitation? In fact, in the legal systems of many countries around the world, “killing relatives for the sake of justice” is discouraged, and “protecting relatives” is exempted because such situations are indeed too complicated.

So, let’s modify the title:If “someone” is a relative or close friend of yours who isn’t suspected of any crime but is a positive COVID-19 case or close contact who doesn’t want to tell others about it, do you feel a responsibility to report it? Or would you help them keep it secret?

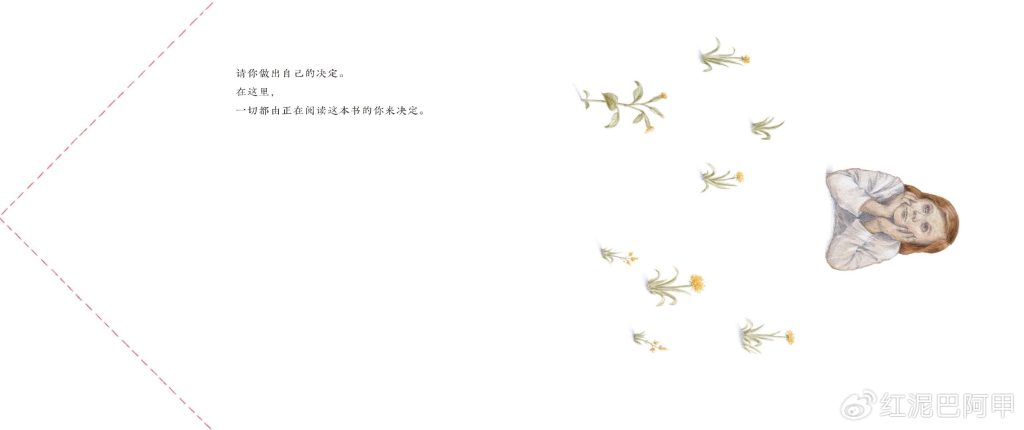

In fact, the “moral dilemmas” we encounter in life are often more like this last type of situation. As Polish picture book artist Iwona Chmielewska writes in her new book, “Fold It Like This,” “Most people want to be good people.” If the question is simplified to “Are you a good person?” most people would undoubtedly choose “yes,” and we often harbor a certain sense of moral superiority. But when faced with a practical choice that involves your own personal interests, especially when helping others requires some degree of sacrifice, or when caring about others’ suffering affects your emotions and disrupts your perception of a “peaceful life,” will you choose to close the door to help or simply turn away? Iwona’s most unbearable image in the book is a post-war ruin. Using origami, the artist creates a door and leaves the reader with the choice: open it or close it? “Just one fold reveals your stance. This book offers you an exercise.”

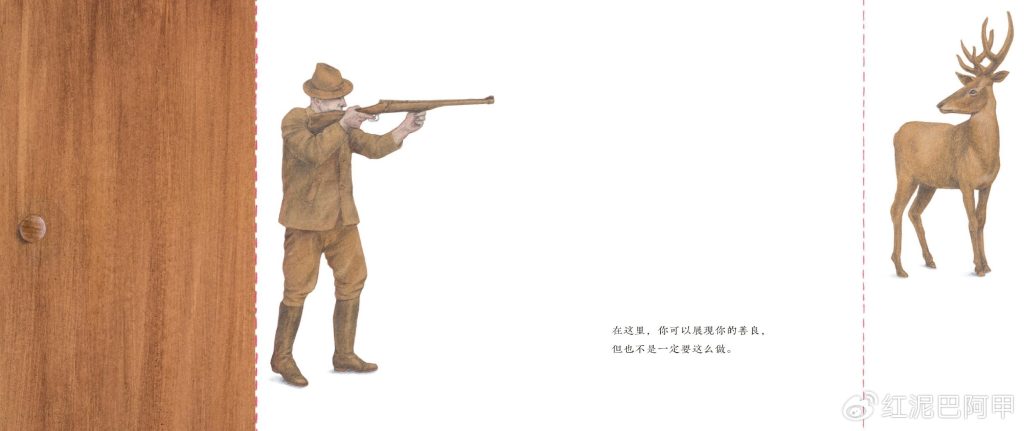

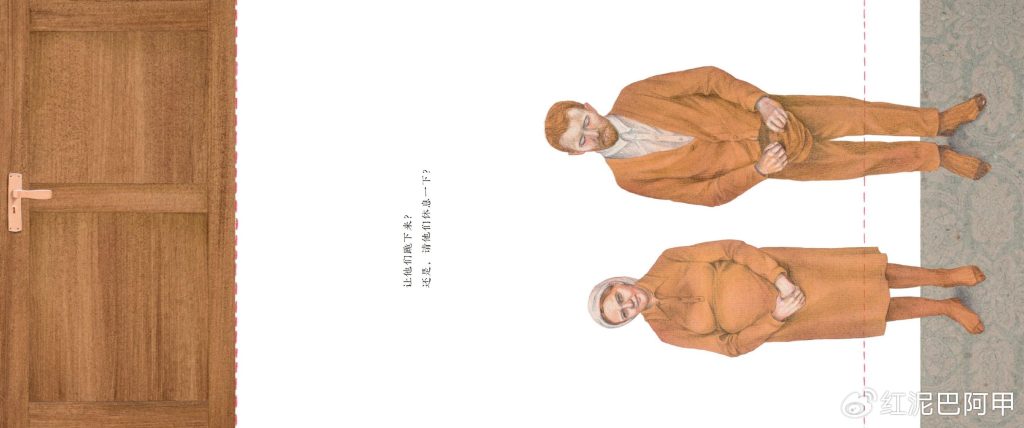

This image easily evokes the Russo-Ukrainian war in Europe in 2022, which saw a massive influx of Ukrainian refugees into other countries, most of whom ended up in Poland. This posed a dilemma for the Poles: should they accept these refugees and provide them with assistance? However, “Fold It Like This” was originally published in late 2021! It wasn’t that Ivana predicted this dire crisis; in reality, localized wars have never ceased on this planet, such as the intense Syrian civil war a few years ago. The refugee influx, directly or indirectly caused by these wars, has had a significant impact on EU countries, including Poland. Poland has been quite reluctant to accept refugees from the Middle East, accepting only over 5,000 refugees in the first nine months of 2021. Furthermore, a raging migrant crisis has occurred on the Polish-Belarusian border. Some of the questions in the book are probably Ivana’s own feelings: “How should we treat different lives? This needs you to decide. Let them kneel down? Or, ask them to rest? How do you want to treat them?” This situation changed dramatically in 2022. According to data released by the European Union in June 2022, since March, Poland has granted temporary protection status to 675,085 Ukrainians, two-thirds of whom are women and children, and more than half of them are children under the age of 18.

Obviously, such a topic is quite weighty even for adults, so wouldn’t it be too complex for children? If only through words, I can’t imagine how to explain such complex moral dilemmas to children. Yuval Noah Harari, author of Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, once said in a speech, “Morality is about a deep understanding of human suffering.” While this is true, it’s also an area where simple consensus is elusive. How can we explain this to children? Fortunately, Ivana is an artist who excels at provoking readers through the visual design of books. Readers have witnessed her extraordinary skill in “The Eye,” which won the Bologna Children’s Book Award. She simply inserted a pair of holes in the pages, but each page offers a surprise, broadening their horizons and eliciting a powerful experience, extending from the physical eye to the spiritual eye. The book is written in simple, poetic prose; Ivana doesn’t preach, but readers’ minds will be stirred as they experience it firsthand, and they will gain unique insights based on their life experiences and reading experience. Both children and adults will gain a wealth of insights.

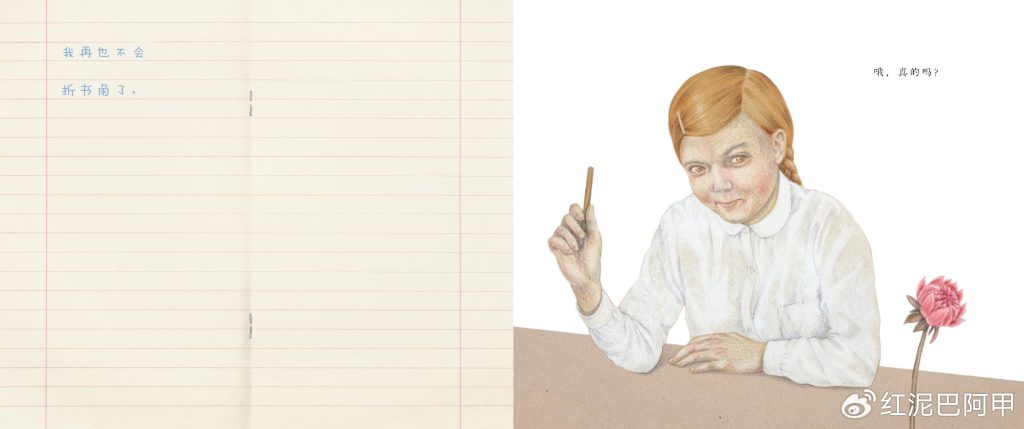

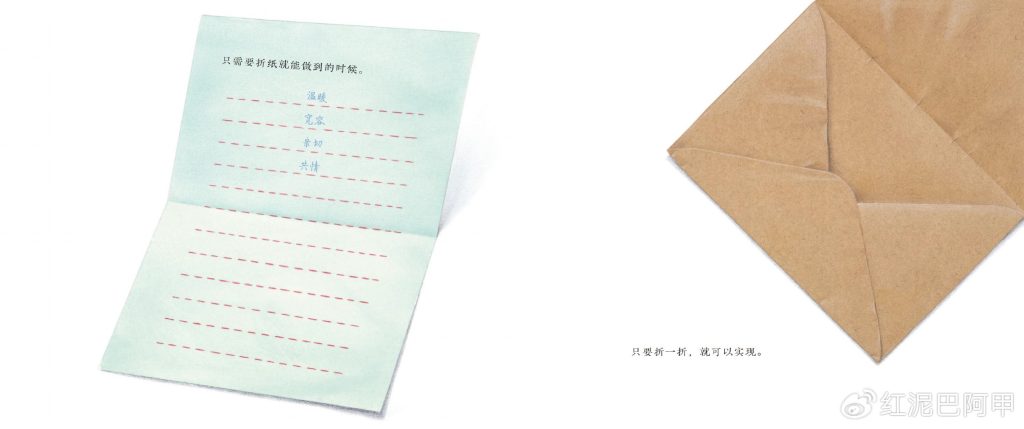

“Fold It Like This” is another visual paper game. If you were to ask me, “How should I teach this book to children?”, my advice is to “play” with them. A Korean reader suggested buying two copies: one for collection and the other to cut out the pages and try folding them individually. This will give you a stronger sense of the experience! Of course, you can also fold just one copy. The artist provides red dotted lines for reference. Fold along them and see how it turns out. Some parts, like the page with the prince and Cinderella, require two more folds to create the staircase effect, and the piano cover also requires two folds to achieve a realistic effect. Overall, however, the origami in this book is very simple and easy to imitate. For example, the paper hat and sail scenes can be easily replicated with your child by drawing on their own blank paper.

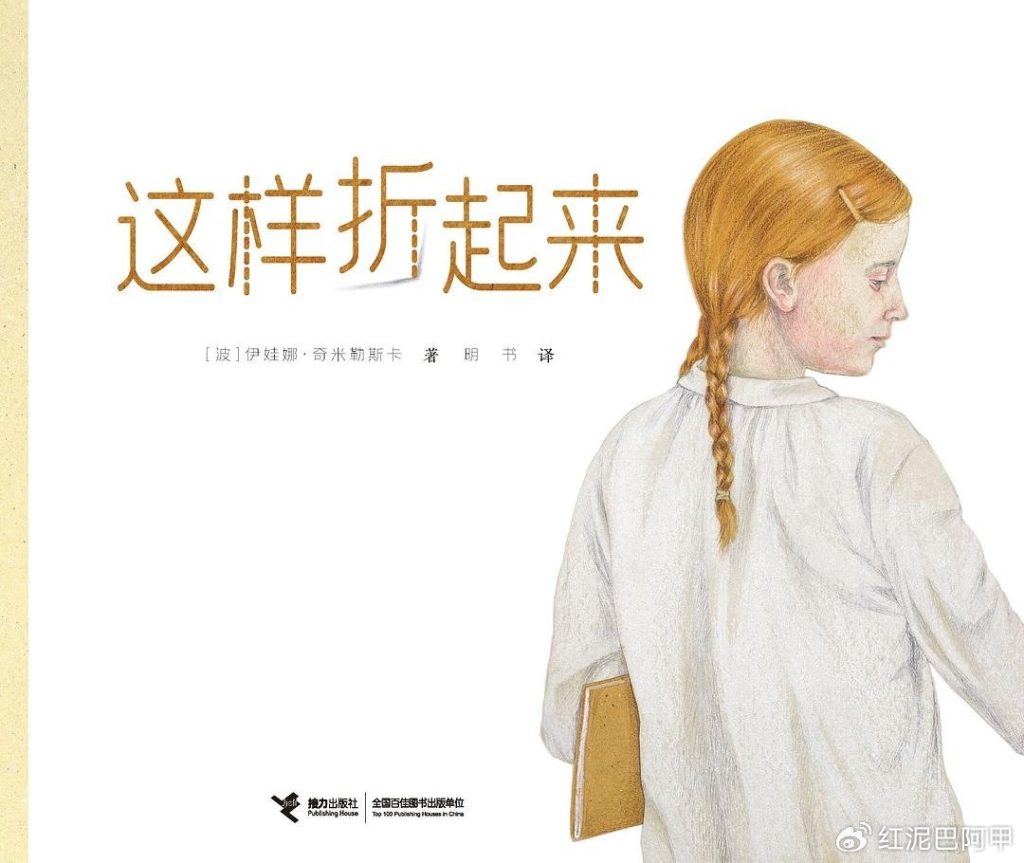

Preserving the book intact (without cutting the pages) is also crucial. Although this book focuses on posing various experimental questions, Ivana skillfully weaves the images together into a roughly coherent story. The jacket depicts a girl holding a brown notebook. Pulling back the front flap reveals the girl’s right hand caressing the back of a boy wearing an origami hat. They look very much like a brother and sister. These siblings appear interspersed throughout the book, and the envelope and dahlia in the girl’s hand continue to the end. The envelope’s letter unfolds, and the dahlia, half-opened, blossoms fully, seemingly symbolizing the girl’s growth and maturity. The meaning of this flower varies across cultures. In Western culture, one meaning of the dahlia is “finding inner strength,” making it a perfect gift for those going through difficult times and in need of support. The flower itself is unique and vibrant, symbolizing a woman’s elegance, kindness, beauty, and dignity.

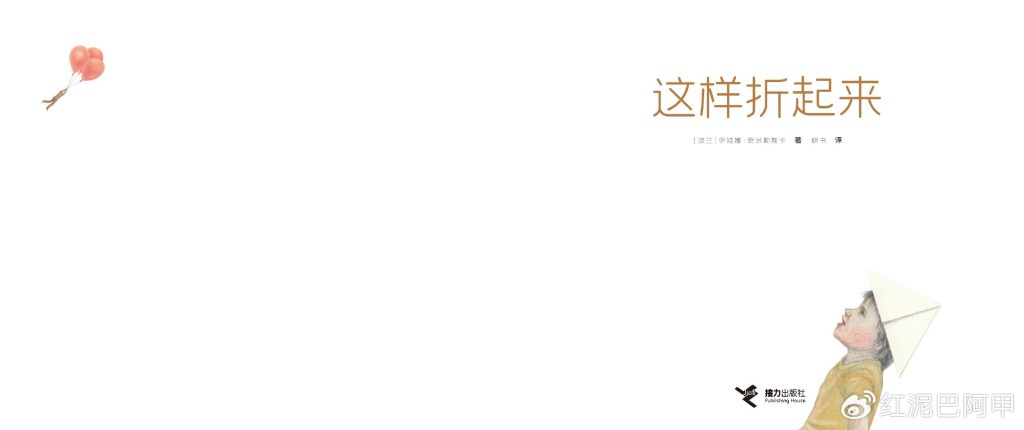

The book’s story is seamlessly guided by this sibling duo, drawing the reader in. The boy in the origami hat on the title page gazes up at a man flying in the sky clutching a red balloon, lending the book a fairytale feel. The sister is a girl going through puberty, while the brother retains the aura of a child full of fantasy, making the book appealing to a wider age range of children. The man hanging from the balloon offers a subtle suspense: where does he come from, where is he going, and why does he take to the sky? Readers must turn to the end to find out. The book, then, resembles a small play on paper, with characters that engage the audience, and even a degree of control over its trajectory.

What’s truly striking about this experimental paper play is that it addresses a series of complex moral issues in a way that children can participate. Rather than posing a question initially, the artist first lets readers practice folding a corner of a book, creating a playful, dynamic effect. The artist also uses fairy tales to immerse readers in a specific situation. Then, starting with simple tasks, the work gradually expands to increasingly difficult issues: children’s rights, the protection of the vulnerable, animal welfare, sexual harassment; and moving from seemingly harmless everyday pranks to war, refugee relief, wildlife protection, the relationship between humans and animals, and so on. The artist doesn’t define these issues; instead, within a simplified and reconstructed situation, the reader is asked to choose their own stance. This choice is made through the use of folding paper, similar to the choice of pressing a key on a computer, but folding paper involves a prolonged and more tactile process, creating a more direct impact and leaving a deeper impression.

This book doesn’t directly tell readers: What should you do? Which approach is more correct? Instead, it allows readers to experience their own true feelings through origami. When guiding children through the reading process, I think wise adults should even temporarily step away and let children conduct such experiments in a more private state. Doing good or doing evil won’t cause any actual harm, but through these positive and negative experiments, children can face their truest feelings.

In more traditional moral education, people tend to simply teach children the so-called standards of good and evil, expecting them to act according to these standards. The “good children” raised in this way are more likely to become those who please adults. Once they are free from constraints, they may be more willing to reveal their suppressed side. However, children with authentic emotional experiences are more likely to demonstrate true moral courage when they make their own choices rather than follow established rules. This is because their choice to do good is motivated by inner joy and peace. I believe this is precisely the value of this experiment.

Thanks to artists like Ivana Chimierska, children are so lucky to have such a game book on their journey to becoming human beings!

Written in Beijing on November 27, 2022