“The Cat and the Young Pied Piper” is a fantasy novel specially created for children. It has rigorous logic and ingenious ideas, and the reading pleasure is no less than any classic fantasy work.

Exquisite structure

The novel opens with a strange ensemble: a talking cat, a group of mice, and a flute-playing boy. They’re on their way to the somewhat remote town of Hubovard, where they’ll perform a Pied Piper exorcism of rats. To put it bluntly, they’re going there to swindle money. Author Pratchett leaves no room for mystery here. The novel’s original English title literally translates to “Magic Maurice (the cat) and his band of educated mice.” It’s a fairy tale trope: these cats and mice can talk, think, and set traps. And the boy, Keith, who’s being “led,” initially seems rather clueless.

Just as readers anticipate a “Pied Piper of Hamelin”-style drama, the story takes an abrupt turn. Though the town is suffering from a severe rat infestation, the rat catcher seems to have everything under control, leaving the city destitute. Most bizarrely, all the other rats (the normal, dumb ones) have vanished! Perhaps it’s not too much of a spoiler to reveal this is a conspiracy orchestrated by the rat catcher, because there’s an even more terrifying plot further down the line, one that threatens even the survival of humanity. At this critical juncture, when the story seems hopeless, the fantasy novelist surprisingly doesn’t resort to magic, but instead decisively untangles the knot using the same technique Alexander the Great used to solve the Gordian knot. Finally, light has been cast upon the clouds.

Upon first reading this, I thought the story was over, but turning the pages, I discovered there was still a fifth to go. I couldn’t help but wonder, what else does the author have to say? It turns out there’s a climax—the Pied Piper truly arrives! Perhaps this final fifth is what makes Pratchett transcend most ordinary writers and become a master of fantasy. He asks and attempts to answer a “real question,” but wisely leaves no “standard answer.” This perfect ending embodies his mastery.

Story Collection

If you are familiar with fairy tales and juvenile fantasy stories, you will meet many “old friends” in this novel.

The “Adventures of Mr. Bunny” that permeates the entire book is clearly Miss Potter’s “The Tales of Peter Rabbit,” or more precisely, the “World of Peter Rabbit” that encompasses all the little books. At the end, when discussing it, the mayor confesses that he loved the books, but never really liked the rabbit, preferring the supporting characters. Indeed, in this novel, we seem to vaguely glimpse the qualities of Miss Potter’s mischievous kittens and “bad mice” in the protagonist.

By the way, do you know the mayor’s last name? The novel doesn’t specifically emphasize it, but interestingly, his daughter’s name (Malicia) appears from the very beginning, and it seems to emphasize throughout that her last name is Grimm—the Grimm of the Brothers Grimm. Ironically, Malicia’s “Grimm’s Fairy Tales” were written by the Grimm sisters. Malicia lives in a fairy tale, while her father, a mayor named Grimm, doesn’t believe in fairy tales (despite loving them as a child). Like the mayor, the adults don’t believe in them either. Ironically, in this story, they’re saved by a child and a mouse who “mistakenly” believe in them.

Besides Peter Rabbit and the Grimm’s Fairy Tales, Pratchett also tucks Easter eggs into this novel: The Pied Piper of Hamelin is the most obvious; the mice whose intelligence is awakened by something they ate naturally reminds people of O’Brien’s The Mice of Nim (1972 Newbery Medal winner); the idea for the Mouse King clearly comes from German author Hoffmann’s classic fairy tale The Nutcracker; and the numerous references to Puss in Boots in the book are clearly a reflection of the relationship between Morris and Keith…

Aims to be ironic

In fact, in addition to the obviously borrowed ideas mentioned above, there are many places in Pratchett’s works that subtly borrow logic from other classic works. If you happen to pay attention and think about it, you can’t help but trigger a series of associations.

Most writers hesitate to be told their work “resembles that of a predecessor,” and even occasional creative “collisions” inevitably lead to a defensive response. However, Pratchett seems to deliberately make his borrowing known to the reader, as displaying creativity or showing off his technique isn’t his primary goal. He says his story seems primarily intended to draw the reader’s attention to issues. Since a single novel typically can’t contain too many issues, he employs extensive borrowing, compelling the attentive reader to engage with the subject. This technique is similar to the use of allusions in classical Chinese poetry; appropriately applied, it can spark endless associations within a short verse.

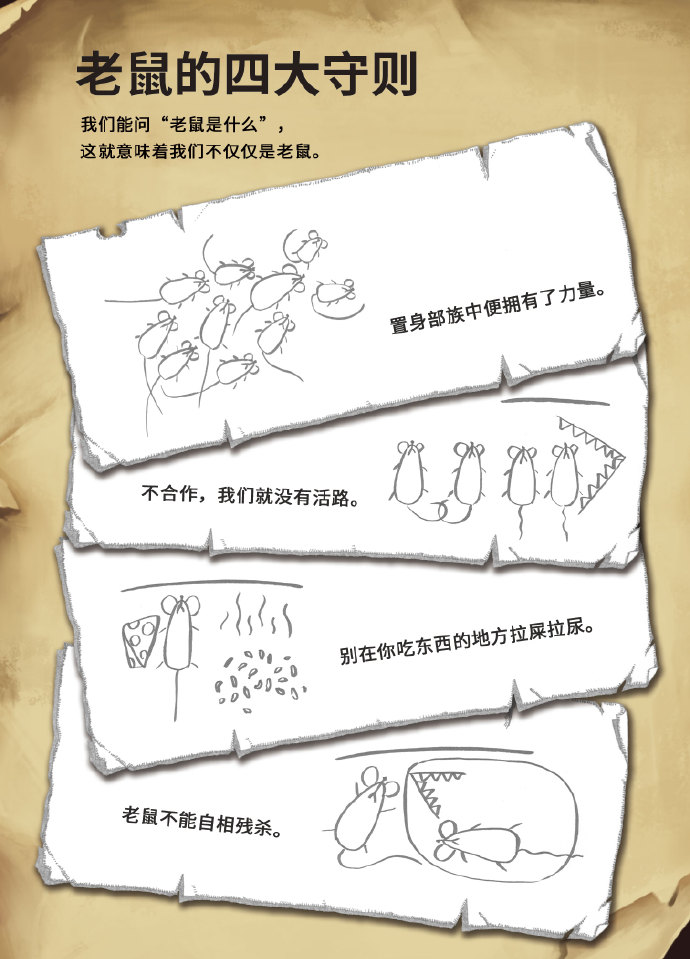

For example, the intelligent mice in the novel are most directly related to The Mice of Nim. The mice in that novel escaped from a laboratory, while this novel only briefly mentions their origins, leading readers to assume that they are “the result of technology.” This is the benefit of borrowing, because Pratchett is truly concerned with their future. When they begin to gain human-like intelligence and communication abilities, how will they build a society? How will they get along with humans?

This is a big question. Perhaps Pratchett also wants us to think of another sci-fi classic, “Planet of the Apes,” a popular science fiction novel and film series in the 1960s and 1970s, which was remade into the “Rise of the Planet of the Apes” series in the 2000s. It’s a rather heartbreaking yet deeply moving series, in which we see the gradual decline of humanity amidst technological advancements, while the true “humanity” must be sought in the enlightened apes.

Pratchett’s mice often embody glimpses of “humanity,” such as Blackie’s remarkable ability to forgive the bloodthirsty humans during the barn showdown. However, they face a similar choice to the apes: they dream of a paradise undisturbed by humans, but that island seems to exist only in dreams; if forced to coexist with humans, they face either ruthless extermination or enslavement, or a terrifying rise to power, ultimately destroying humanity. This antagonistic, often necessitating annihilation, mirrors human society, evoking the Cold War, racial conflict, religious clashes, underprivileged ethnic groups, and the underclass. The otherworld beneath London, beautifully depicted by Neil Gaiman in his classic novel, Utopia, echoes Pratchett’s depiction of the subterranean mouse society.

Discworld Convenience

But Pratchett is not a sociologist, nor does he aim to write intellectual flares like “Utopia” or “Leviathan” (he’d rather borrow them). His fascination with stories borders on religious belief. Those who love to listen to and tell stories must first seek complete pleasure, basking in the sunshine of the imaginary world. Humans immersed in imagination are particularly relaxed and often defenseless, allowing interesting ideas to be absorbed through casual breaths, or even seep through their pores at who knows when.

I don’t know how the idea for Discworld entered Pratchett’s mind. When I first read The Cat and the Young Pied Piper, what puzzled me most was how it seemed to have no connection to the Discworld at all. Later, I learned that the story takes place in the city of Hubertus, which is in the Discworld, so it’s somewhat connected. Also, Mr. Death, who can actually negotiate, is a very important interlude in that world.

It turns out this flat-panel world, carried across the universe by four elephants atop a giant turtle, originated in Pratchett’s 1983 novel, The Colour of Magic. The novel is inventive and lively—a bit too lively, to be honest. It feels more like a playful, unbridled creative tale, a bit like an early Tintin story (perhaps before The Blue Lotus). It’s incredibly entertaining, but the author doesn’t seem to have much to say.

Let’s consider it as a framework for the initial map of the Discworld. In “The Color of Magic,” the reader is taken to the edge of that world, nearly swept over a waterfall, and discovers that the people there, like us, possess good and evil, desire, greed, but also integrity, courage, and responsibility to others and the world. Therefore, telling the story of that world is actually telling the story of this world, simply as a mirror image.

The slight difference is that there is magic in that world, and the supernatural forces that we see in myths, fairy tales, and fantasy stories are part of reality in the Discworld. However—and this is very important to note—magic in the Discworld is extremely limited!

Fantasy magic

The secret to Pratchett’s success in writing about magic lies in setting appropriate limits for the magic of his imaginary world. In an interview, he bluntly stated that setting limits for magic is the first rule for writing novels with magic. “If you could do anything with the flick of a finger, where would the fun be?”

Take, for example, the down-and-out wizard Rincewind, expelled from Netherworld University in “The Color of Magic.” He knows nothing but one of eight basic spells, intricately integrated with the fabric of time and space, that has inexplicably found its way into his head. This spell is a torture for him, unusable in normal circumstances, only to suddenly and unconsciously surface in moments of deepest despair or dire need. Doesn’t it sound a lot like Duan Yu’s Six Meridians Divine Sword in “The Demi-Gods and Semi-Devils”? Even Jin Yong ultimately allows Duan Yu to master this magical martial art. But Pratchett simply doesn’t let the protagonist and the reader revel in this, forcing you to wait in agonizing anticipation. Ultimately, you realize that waiting for magic is better than using your brain and courage.

Maurice the tomcat and his group of mice possess no magical powers other than the ability to speak and think. Keith the boy is even more mediocre, while Malicia the girl possesses only a boundless imagination. Yet, as you read this book, you sense that this strange team grows ever more powerful. Why is this so? From the mice’s perspective, the blind Dangerous Beans seems the most useless, yet he becomes the soul of the group, even the worldly-wise Maurice willingly sacrifices his own life to save his. Why is this so? When the antagonistic humans and mice finally come face to face, they surprisingly find a third path to harmonious coexistence. How did this happen? It all stems from another, more ancient and profound magic: thought.

When the mayor (representative of humans) and Black Skin (representative of rats) looked each other in the eye, the human asked, “Can you really speak? Can you really think?” The rat proposed, “If you pretend to think that rats can think, then I agree to pretend that humans can think too.”

Immersed in fantasy, we “pretend” that humans (and children, of course) are capable of thinking. This thinking isn’t about immediate necessities, housing, cars, and career advancement, but rather about larger questions like how different human species can coexist harmoniously in this world. This may seem far-fetched, but if we truly contemplate it, we realize it’s deeply connected to our very survival. The magic of fantasy can offer us a different perspective: even humans and mice, humans and gorillas, can get along harmoniously, so what about…?

Of course, we also know that after closing the book and leaving the cinema, most people will continue to live their lives as usual, “because some people’s minds cannot be changed even with an axe.” But some people will still change, especially children.

The magic of fantasy, though limited, is effective nonetheless. At least that’s what people like me, who are fascinated by stories almost as if they were religion, prefer to believe.

Ajia …

Written in Beijing on October 28, 2017