The “Gunash Bunny” picture book trilogy has recently been reprinted. This series is one of my favorite translated books, perhaps because the stories of a father and daughter growing up together remind me of myself and my daughter. The final letter from the father, an old pen pal, to his daughter was particularly moving. I found an opportunity to write an email to the author, Mo Willems, to pay tribute to him and express my gratitude.

This series of books is also the one I’ve discussed the most with editors of all my translations. Throughout the publication of the trilogy and subsequent reprints, I went through three different editors, each of whom repeatedly asked me, “Why is ‘Gunash Bunny’ translated as ‘Gunash Bunny’?” Or, more subtly, “Can ‘Gunash Bunny’ be renamed? Perhaps something more child-friendly?” Each time, I had to explain the title from the beginning (of course, I also hope the previous editor has left behind some editorial notes as a reminder). But I’ve always been reluctant to write a direct explanation (perhaps this explains Mo Willems’s decision not to explain the original title, ‘Knuffle’). I believe readers would be happier if they could find a satisfactory explanation themselves. And indeed, some readers have written to tell me about their children’s amusing reactions to reading.

But it’s almost been ten years since I translated the first book, “Gunash Bunny.” Perhaps it’s worth giving a few spoilers, which would be a different kind of fun.

In fact, when this book was first submitted to the editor, there were two versions: “Gunash Rabbit” and “Gnarfo Rabbit”.

Let’s talk about the original English name first: Knuffle

Bunny. Knuffle is a word that does not exist in English. It is likely derived from Dutch because the author Mo Willems’ parents were Dutch immigrants. They gave birth to Mo Willems in Chicago shortly after they immigrated to the United States. When he was four years old, his family moved to New Orleans, where he grew up. In the third book of this series, we see Tracy go to the Netherlands to visit her grandparents. So is Knuffle a word?It must beWhat about Dutch? I’ll talk about that later. But according to Dutch pronunciation, it should be pronounced “K‑nu-ffle,” with a slightly stronger first “K.” That’s about it. But if you think of it as English, the “K” is usually silent, like “knife.”

So when deciding on the translated title, we considered imitating the Dutch pronunciation. Initially, we considered the translation of “Gulliver the Bunny”, which obviously has a bit of the shadow of “Gulliver”, hoping to have such an association. But why were we not so keen on this translation later? One of the reasons is that this book (at least the first one) is aimed at children who are just learning to speak (of course it can be compatible with upwards), and the association of “Gulliver” has no meaning to them. The more important reason is that we need to grasp where the focus of the story lies. After reading it over and over again, I am convinced that the focus of the story is on pronunciation — of course, this is superficial, and the deeper level is the leap in the child’s growth, which is manifested by overcoming certain pronunciation difficulties. This is how I explained it in an email many years ago:

The word “knuffle” doesn’t exist in English. The author uses it primarily to point out that English children have difficulty pronouncing it, confusing “n” with “l,” “ffle” with “gle,” and “pple.” In Chinese, however, the most common mispronunciations for children learning to speak are “k” and “g,” often pronounced as “d.” They also have trouble distinguishing “n” from “l,” and, most ridiculously, “sh” as “j” or “x.” Therefore, “knuffle” might have been pronounced “dulaji”—that’s how the translation came about.

Looking back today, I can understand it better. Knuffle is a “weird foreign word” in American English, and there is a very important principle in translation: the “equivalence” principle.When a word is strange or difficult to pronounce in the source language (especially for small children), the word we translate into the target language should also be as strange and difficult to pronounce as possible.——Especially when the effect of this pronunciation is an important clue to the story.

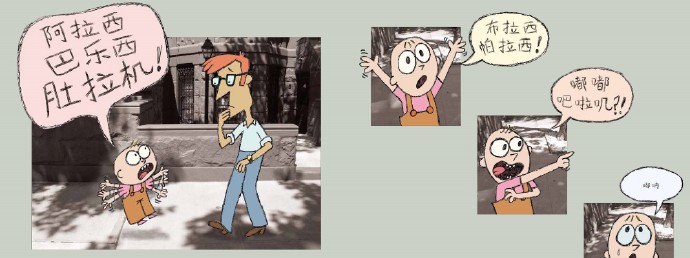

This word plays a crucial role in the development of the whole story. When Tracy was anxious and couldn’t find the little rabbit, she couldn’t pronounce the sound of Knuffle accurately. Look at the English, what sound did she make?

“Aggle flaggle Klabble!”

“Blaggle plabble!”

“Wumby flappy?!”

“Snurp.”

In Chinese, the corresponding translation is——

Arasi, Balesi, belly machine!

Brasi

Palasi!

Dudu

Balalaji? !

Du Na.

These translations all correspond to “Gunash” -

The word “gu” could not be pronounced, so it became “a”, “ba”, “bu”, “du”, “pa”, and “du”;

The “na” sound could not be pronounced, so it became “la”, “le”, “la”, and “na”;

Since the pronunciation of “shi” cannot be made, it becomes “xi”, “ji” and “ji”.

At the end of the story, the child finally found it and suddenly relaxed completely, and then he could send out the words that he had found particularly difficult.“Gunash Bunny”!——At this moment, the child feels so accomplished! ——“This is the first word Tracy learned to say.”

Just imagine, if the name of the little rabbit was just “Hug Bunny” or “Fluffy Bunny”, which is easier for young readers to pronounce, where would this sense of accomplishment come from?

Of course, the biggest drawback of the name Gunnash Bunny is that “Knuffle” itself has no meaning. However, Knuffle may have meaning in Dutch (though it’s pretty certain it doesn’t in English either). Last year, I attended an event in New York City and met a British translator who has lived in the Netherlands for many years and primarily translates children’s literature from Dutch into English. I asked her if “knuffle” was a Dutch word. She said there’s no such word in Dutch, but there’s a very similar word, perhaps its origin: the Dutch word knuffel, which means hug/cuddle. The Dutch pronunciation is slightly different, similar to “knuckle.” So, while the meaninglessness of “Knuffle” itself isn’t necessarily inappropriate, it’s not necessarily flawed. While translating from Dutch to Chinese might be flawed, translating from English to Chinese, if both are meaningless, why not?

Why did Mo Willems insist on creating a meaningless English word to embarrass American children? I asked Leonard Marcus about this, but he didn’t have a definitive answer. He suggested it was more of a joke, something Williams was known for. I think that’s a possibility. American culture appears to be very inclusive, but children living there (especially those from minority groups or foreign backgrounds) strive to look like everyone else. Willems experienced similar hardships as a child. Born to Dutch parents, his mother “surprisingly” worked as a lawyer, making her somewhat of an outsider among her classmates. So, I suspect his creation of the word “knuffle” was also a form of revenge, though certainly a joke. This “revenge” is similar to his pigeon, which provokes endless “nos” because he grew up surrounded by them.

Of course, I chose “Gunash Bunny” with no intention of “revenge”. I just treat it as a pure joke on the little guys.

Finally, here is the “test feedback” sent by a mother:

Teacher Ajia, this is how my 1‑year-10-month-old son named this little rabbit:

The first retelling (not after I said it, but after I guided him to remember it): called “Guna” rabbit

Second retelling: “Gunash” Bunny

The third retelling (a day later): “Pinocchio” Rabbit (perhaps influenced by Pinocchio) looked very proud of himself after he finished telling the story.

I told him that this little rabbit also has an English name, Knuffle. You can call him Knuffle Rabbit or Gunash Rabbit. What do you like to call him?

“Gunash Bunny!” came the loud and cheerful reply.

Written in Beijing on December 4, 2016