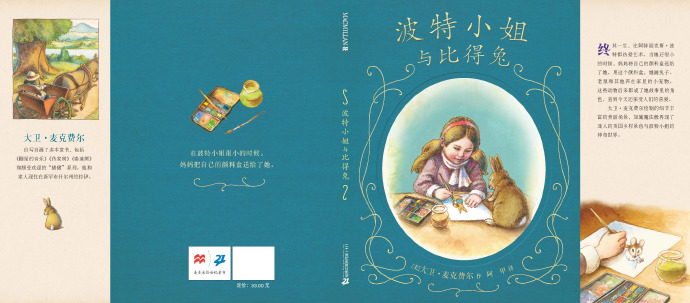

I’ve had the great honor of translating the Penguin edition of Beatrix Potter’s “The World of Peter Rabbit,” and I’m also honored to have translated David MacPhail’s “Miss Potter and Peter Rabbit.” Like MacPhail, Miss Potter is a hero of mine, and I’m grateful to him for creating this picture book about Miss Potter’s coming-of-age story for children (it’s also the first one I’ve ever read). I couldn’t resist sharing some more information with older readers. You can delve deeper into this book, and if you’re interested, share it with your children.

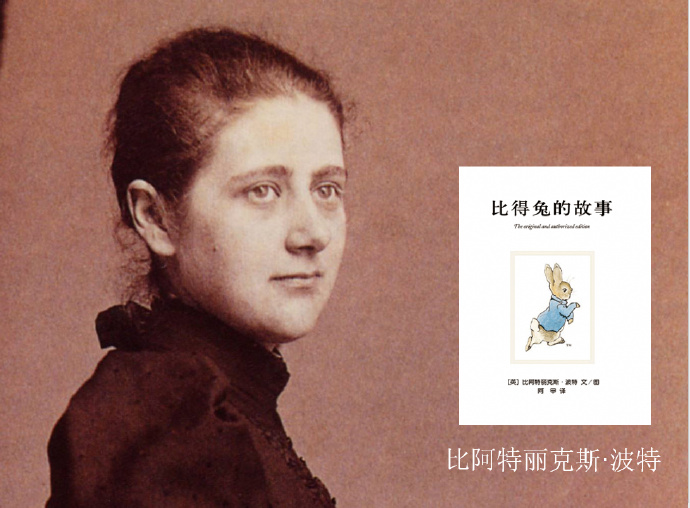

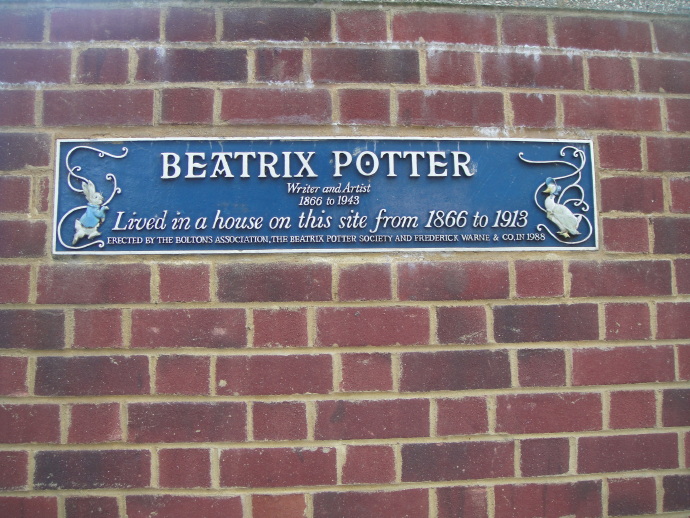

Although Miss Porter was born in the middle of the Victorian era in England and died during World War II, and her life span is quite long ago, many people still remember her because of her many remarkable contributions to the world. They have collected and compiled a lot of relevant information. There are at least three rigorous biographies alone. Her diaries, letters, and works have been preserved quite well. Her farm, old house, and furniture in the Lake District of England have also been preserved very well. Therefore, we can basically have a pretty clear understanding of the outline of her life. If necessary, we can go there to see it in person.

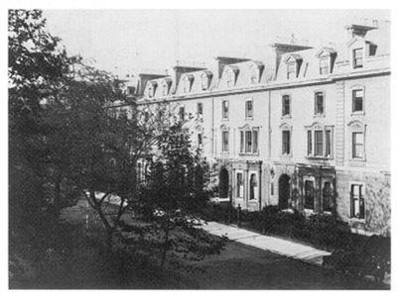

The book opens by mentioning that Miss Porter was born into a wealthy family, but her parents didn’t spend much time raising their children themselves, instead leaving them to nannies and governesses. Indeed, Miss Porter later described the large house at 2 Bolton Gardens in London where she and her brother were born as a “loveless birthplace.” While their parents did love them and provided them with excellent material conditions, the lack of parental companionship still left them feeling a sense of loss.

Number 2 Bolton Gardens (photo taken by Miss Porter’s father Rupert in 1889)

Miss Porter’s birthplace, 2 Bolton Gardens, London

The original mansion was destroyed by bombing in World War II and has now been converted into a primary school.

Miss Porter’s parents, both originally farmers in northern England, rose to wealth through tireless hard work, becoming emerging industrial tycoons in the Manchester area. Her grandfather, a major player in Manchester’s textile industry, later became an MP in London and actively participated in politics. Her maternal grandfather, through his successful overseas trade, also achieved international influence. Both placed great emphasis on their children’s education and possessed artistic taste, including avid art collectors. Her maternal grandfather’s collection included numerous landscapes by the Impressionist master Turner. Miss Porter’s father, Rupert, was a London lawyer and a skilled investor, accumulating considerable wealth through both personal accumulation and inherited wealth. Her mother, Helen, also amassed a substantial fortune, primarily through inheritance. When Miss Porter was born, the family, with a butler, housekeeper, cook, groom, and several servants, was considered a distinguished family. However, without a title and limited social circle, they were still considered upper-middle class.

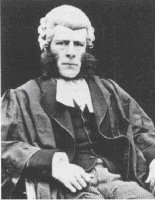

Miss Porter’s parents

A child living in such a home should naturally feel happy, but Miss Porter recalls her childhood as one of rigidity and loneliness. Her father was away on business, often on business trips, while Rupert was active in various social clubs. Her mother was busy directing servants, entertaining guests, and socializing at other homes. The child, cared for by a surly Scottish nanny, spent most of her time in the children’s playroom on the third floor, away from the adult world downstairs. Miss Porter usually played alone, occasionally seeing the children of visiting relatives. This situation did not improve until her younger brother Bertram arrived, when she was almost six. It was indeed a rather lonely childhood! Miss Porter’s first biographer was so moved that he even imagined the nursery window barred with iron bars. In fact, there were no bars at all, and the view from there was breathtaking.

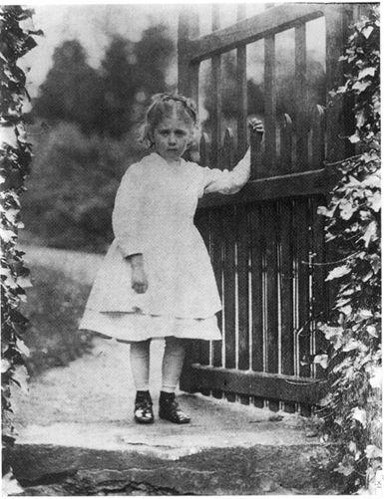

Miss Porter in her childhood

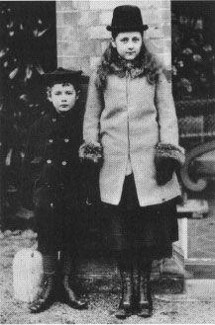

Photo of Miss Porter and her brother

Fortunately, Miss Porter had a passion for painting from a young age. This solitary activity must have helped alleviate much of her loneliness. Her artistic nurturing came primarily from her family. From a young age, she often visited her grandparents and her grandmother’s home, though her grandfather sadly passed away five years before she was born. Both homes were filled with their collections of famous paintings, and the furnishings and furniture were elegant and antique. Miss Porter later became a collector of these works. However, even as a young girl, it was the natural surroundings of the country estate that most captivated her. Her grandfather’s Camfield Estate spanned over 300 acres and even featured a cave! He hired a leading landscape architect of the time to design and transform it into a renowned scenic spot. In that environment, Miss Porter developed a close connection with nature and a love for observing beautiful things.

Her parents also passed on to her the ability to feel and express beauty. Rupert and Helen already had a deep artistic background: Rupert loved painting in his early years, often sketching in his sketchbook even while studying at law school. Later, he became fascinated with photography and became a skilled amateur photographer; Helen excelled in watercolor landscapes in her youth, and her works are still auctioned and collected. Some critics believe that her paintings have beautiful composition, but are “too subjective.” The two of them always carried sketchbooks with them when they went out, and would write and draw in them at any time. Rupert would often draw while telling his daughter interesting things. Miss Porter developed this habit naturally. It is said that once someone gave them a rare pineapple, she quickly drew it before the servants could cut it.

Landscapes painted by Miss Porter’s mother when she was young

The book recounts one of Miss Porter’s happiest childhood moments, when Helen gave her watercolor box to her daughter. She kept the box throughout her life. Various sources indicate that Miss Porter’s relationship with her mother was strained, even distant. However, her mother’s encouragement and affirmation of her daughter’s painting played a significant role in her future success in this field.

By comparison, her father, Rupert, had a more direct and profound influence on her. Although he was often away from home, he was incredibly kind and patient with his daughter and son. He also had a wonderful habit of writing down interesting things he saw upon their request. Rupert and his daughter often exchanged notes. When his daughter asked him if he had seen anything interesting outside, he would patiently write down a long paragraph. Rupert’s photography required models. At the time, cameras took a long time to process, requiring him to sit facing the lens for several minutes before taking a single shot, which required repeated adjustments. Most people wouldn’t have endured this, but Miss Porter loved being her father’s model because it allowed her to spend more time with him. Even better opportunities included fishing trips with her father or outdoor photography sessions, where they had more time to interact freely. This was how Miss Porter learned photography from her father, and also how to observe like a photographer.

Rupert was well-connected in the art world of his time, associating with numerous artists, most notably Millais, one of the three great Pre-Raphaelite artists. Miss Porter’s favorite painting was “Ophelia.” Millais frequently visited the Porter family’s farm in Scotland, where they vacationed, and asked Rupert to photograph him. He also frequently invited them to his studio in London. As a child, Miss Porter was terrified of this painter, who often teased her, but she gradually learned from him and received numerous praises and encouragement from the master. Millais once remarked to Miss Porter, “Many people can paint, but you and my son know how to observe.”

Although Miss Porter’s parents did not succeed in making their children feel fully loved, they did a lot of things within their ability, consciously or unconsciously. One of the most wonderful things was to take their children on vacation to the countryside in northern England every summer, which often lasted four or five months.

Originally, the Potters had longed to join London’s upper crust, but their thickly accented Yankees, their upstarts from a family of farmers, and their membership in the niche Unitarian sect (which didn’t believe in the Trinity) made this difficult. Despite this, whenever the warm English summer breezes blew, they couldn’t help but yearn for the earthy aroma of the north. They quickly packed their bags, gathered their children and servants, and headed for their farms in northern England or Scotland. For now, they could forget all about London society. The peasant blood coursing through their veins flowed irresistibly into their daughter and son, who, as adults, chose to leave London behind and settle down in the rural countryside of northern England. Miss Potter even made remarkable efforts to become a true country bumpkin. But that’s another story.

Before she was 16, Miss Porter spent most of her summers in the Scottish countryside. In her “aesthetic dictionary,” beauty was synonymous with the Scottish countryside. When she was 16, her family spent their first summer in the Lake District in northern England, and she fell hopelessly in love with the Lake District, especially the village of Thorley, west of Lake Windermere. Many years later, it was there that she completed the pre-publication revisions for The Tales of Peter Rabbit, and later bought Hilltop Farm, where she gradually settled down.

Miss Porter’s former home at Hilltop Farm (photo taken by Ajia in the summer of 2013)

During their summers in the countryside, Miss Porter and her brother Bertram enjoyed a freedom they hadn’t enjoyed in London. They could go out and play on their own, and when they were older, they could go boating or ride in a horse-drawn carriage. In this beautiful natural environment, their parents relaxed, often playing and interacting with their children. Visitors, many of whom were prominent figures from various social circles, also naturally engaged in conversation with the children, which broadened their horizons. Miss Porter’s broad perspectives in literature, art, and science were in part due to these connections. For example, the visiting Millais gave her a lot of artistic guidance; and the postman she met in Scotland was actually a folk naturalist. Miss Porter’s interest in fungi and her outstanding achievements in this area were largely due to his help, and he also became the prototype of Mr. McGonagall in “The Tale of Peter Rabbit”; and the pastor and writer Mr. Rawnsley, whom she met in the Lake District, spared no effort in encouraging her to publish “The Tale of Peter Rabbit”, and his scientific and rigorous attitude and almost fanatical piety to protect the Lake District environment also influenced Miss Porter’s entire second half of her life.

Miss Porter was often ill while in London, suffering several serious illnesses between the ages of 16 and 19, including eight months in which she didn’t write a single word in her secret diary. This little book also recounts this experience. Interestingly, however, once in the countryside, Miss Porter’s ailments vanished, leaving her feeling strong and energetic. In this healthy, free air, she hiked extensively, painted everywhere, and observed with great interest. The Victorian era, during which she lived, was Britain’s most glorious era. Scientific literacy was widespread, and even young ladies enjoyed reading scientific journals, collecting fossils, and preparing specimens in their spare time. Joyfully immersed in nature, Miss Porter developed a deep interest in natural history. Rupert, noticing his daughter’s particular interest in birdwatching, gifted her a beautiful copy of “Bird Sketches” on her tenth birthday. Miss Porter loved it and treasured it for the rest of her life.

When she and her brother had to return to the nursery in London (which later served as a classroom), they not only brought back numerous fossils and specimens but also raised numerous small animals. Besides the more domesticated dogs, rabbits, lizards, salamanders, tortoises, canaries, parrots, mice, and guinea pigs, they also kept wild animals like ring-necked snakes, wild ducks, bats, hedgehogs, kestrels, and grouse. This reflected both their boundless curiosity and their parents’ astonishing tolerance for this hobby. Many of these animals became characters in Miss Porter’s picture books.

Miss Porter’s childhood drawings

The book also mentions Miss Porter’s painting studies, thanks to her father’s arrangement. Rupert, increasingly impressed by his daughter’s talent in this area, urged her to pursue formal painting training. She studied for five years with a Miss Cameron and later took the National Art Training School exams, achieving distinctions in all of them. However, her enthusiasm for this kind of art education waned as she gradually developed her own perspective and standards for judging artwork, often finding them at odds with her teacher’s. Under the guidance of a mentor, Rupert arranged for his daughter to take expensive oil painting lessons with a renowned teacher. Miss Porter reluctantly completed the course, almost instinctively rebelling against the techniques being taught. This rebellion, however, led her to discover a passion for watercolor and gradually develop her own style. While these lessons didn’t directly benefit her, they did provide a window for the young artist to emerge.

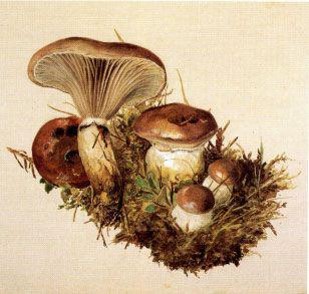

Miss Porter’s paintings of fungi

The book mentions her brother Bertram primarily as a companion growing up, but he was also an artist. Miss Porter admitted that his brother far surpassed her in landscapes and portraits. She herself preferred to paint animals and plants in watercolor, with a certain scientific rigor. She created dozens of watercolors of fungi, which are still included in authoritative encyclopedias. She also had a deep admiration for several of the leading children’s book illustrators of the time, such as Walter Crane, Kate Greenaway, and Rudolph Caldecott, especially Caldecott. Rupert himself was deeply fascinated by Caldecott and collected some of his original illustrations. Miss Porter was a great admirer of Caldecott, even “trying in vain” to copy many of his works. Caldecott’s profound influence can be seen in many of her later works.

Although Miss Porter never attended school, she received a well-rounded education. Even before she was six, her cantankerous Scottish nanny read her countless Scottish nursery rhymes, fairy tales, and folk tales, all of which permeate her little book. From the age of six until she was nineteen, she studied under three governesses, taking specialized assessments and achieving excellent grades in every subject. Homeschooling allowed her to fully pursue her interests. She devoted nearly half her time to painting, and much of her time to natural history research, English literature, French, and German. She wrote fluently in French and conversed quite comfortably in German. At one point, she became a fervent Shakespeare fanatic, assigning herself assignments and assessments, memorizing entire plays in a matter of months.

In short, when Miss Porter wrote The Tale of Peter Rabbit at the age of 27, she was well prepared in every way.

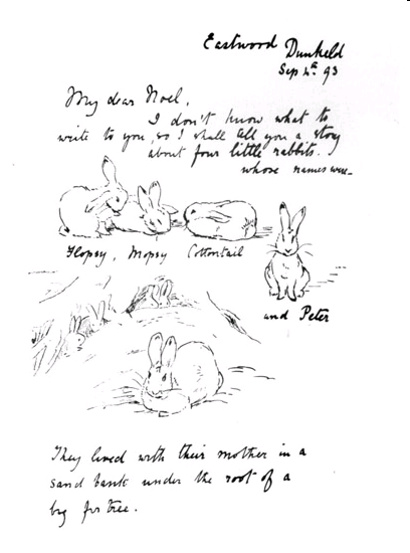

That famous illustrated letter was written on September 4, 1893, while she was spending the summer on a farm in Scotland, busy with painting and her fungal research (which later culminated in a valuable scientific paper). She had heard that her friend’s (and her last German tutor’s) son, Noel, was ill, and she felt compelled to write to comfort him. Remember? Miss Porter’s father often wrote amusing anecdotes to comfort his absent children, so Miss Porter naturally followed suit. But since she had nothing else to tell him, she decided to tell him the story of the four little rabbits. As she wrote and illustrated, a beautiful and lovely story emerged.

The recipient of this famous letter: Noel Moore

A few summers ago, my family and I vacationed in England’s Lake District. On the ferry across Lake Windermere, the captain, upon hearing we’d come from China to visit Miss Porter, was delighted and proudly asked, “Do you know the three things Miss Porter should be remembered for?” I almost guessed the answers, but I was eager to hear his response. He said, first, she was a remarkable writer and artist, the author of so many beautiful books; second, she was a remarkable environmentalist, and the Lake District’s beauty today is largely due to her years of hard work; and third, and this is often overlooked, she was also a scientist, whose vast knowledge instilled in her a deep love for this land. Yes, I happily shook the captain’s hand; what he said was exactly what I had in mind.

In 1913, Beatrix Potter married Mr. Hillis, a local Lake District lawyer, and became Mrs. Hillis. The Hilliss were deeply in love and passionately committed to preserving the Lake District’s environment. They lived together for 30 years until Mrs. Hillis’s death in 1943; Mr. Hillis, unable to bear the grief of his wife’s death, followed two years later. During their lifetime, they donated all their farms in the Lake District to environmental charities to protect them from future overdevelopment. As a result, to this day, the Lake District where they lived retains the natural beauty of its 140-year history.

Written in Beijing on March 7, 2016

The inn next to Hilltop Farm