On May 13, 2015, I visited Professor Cai Gao in Changsha. We chatted for a full day and then again for half the afternoon. During the conversation, we discussed Cai Gao’s book, “Meng Jiangnu Weeps at the Great Wall,” which was then only available in Japanese but is now available in Chinese. We first discussed the dramatic elements in picture book creation, and then, using this book as an example, since I can’t read Japanese, Professor Cai Gao explained it to me in detail, from beginning to end. It was truly enjoyable. I’d like to share it with you.

…

A: I feel that “Mulan” has a bit of a dramatic flavor, both at the beginning and when Mulan comes back. The middle part is more lyrical and artistic conception is developed.

Cai: Yes. Perhaps “Meng Jiangnu” has a bit of that, too. The dramatic quality of “Meng Jiangnu” is primarily a necessity for the story’s entry. It has two main plotlines, and that’s how it needs to begin.

A: That is to say, the background and characters need to be introduced in this way.

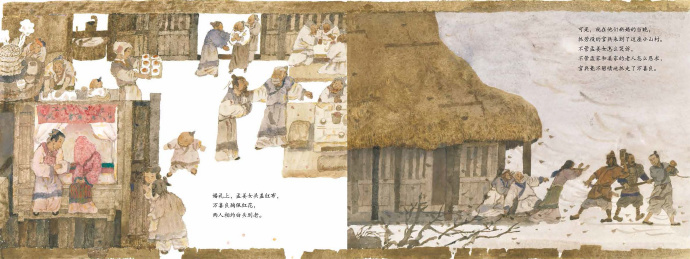

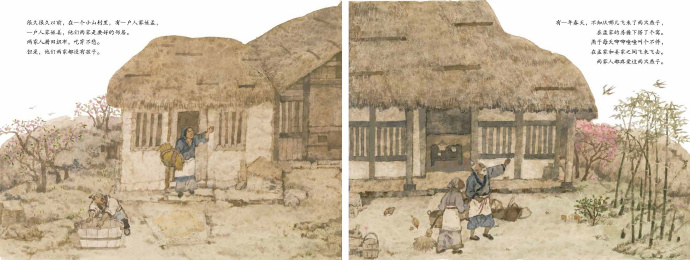

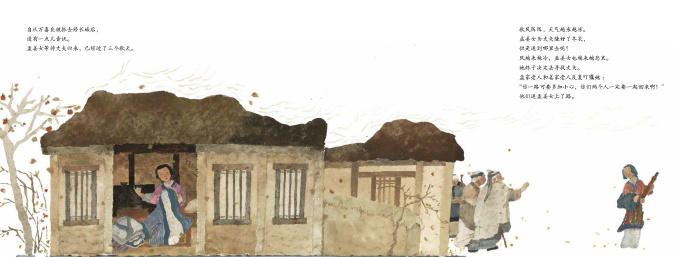

Cai: From the beginning, it needed to create a sense of neighborhood. There’s a saying in the story that the child is from the gourd, so how could it be a child shared by two families? We needed to offer this possibility: the wall between our two homes is like this, so the gourds you planted have crawled into our house. We had to offer this possibility for the reader’s imagination. We also needed water, fields, and the surrounding terrain. We needed to hide here and rest for a while, so the story could unfold. We also needed time for a love story to unfold. And then there were the traps everywhere; without the mountains, there was no place to hide. So, setting up this kind of setting made the story possible.

A: The opening scene on the title page is the main scene that takes place in the first half of the story.

Cai: Then on the next page, the picture is enlarged and the wall is completely removed. Both companies use this kind of stage effect to perform and don’t worry about the specific actual situation.

A: Yes, it is very troublesome to paint the wall.

Cai: It’s both cumbersome and ugly; readers will immediately know they’re two separate families. This is theatrical expression, separating two scenes. Take, for example, the play “Lychees for Red Peaches” that I watched as a child. The drama between the two families takes place on two different floors: the boy’s home on one side, the girl’s on the other. Another example is “Wall Horse,” which also tells a story separated by a wall, but requires the audience to see both stories unfold simultaneously.

A: On the stage, with one setting, two stories happen at the same time.

Cai: In the plays I watched as a child, the boys and girls from the two families could see each other, but the plane had to be open to the audience. In this page, I also have a plane facing the audience. This arrangement can only be done on stage; it’s impossible in real life. How could two houses be like this?

A: The picture can be cut across the page to create a stage effect.

Cai: After cutting it open, a white line remains in the middle, creating a connection and representing the two scenes. This is the flat treatment, completely following the flat effect, unfolding like a stage. (Turns to the next page) The story can be seen by you, by children, and the wall becomes this effect.

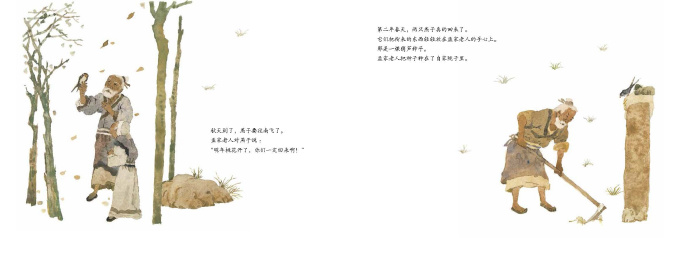

A: The wall on this page (Meng’s old man hoeing the land and sowing seeds) looks short.

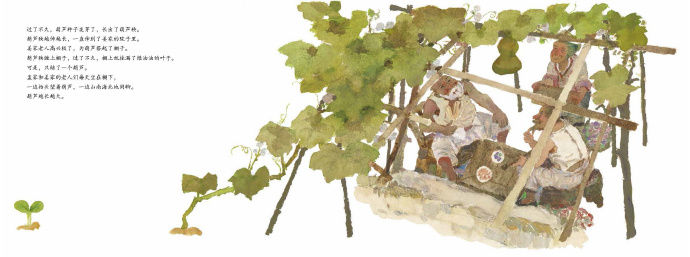

Cai: Over here, people are farming, and there’s a bird on the wall. A child could easily understand it. Then the gourd vine crawls along the wall (turn to the next page, two families are chatting in the shed). I didn’t draw the wall at this point; it wouldn’t look pretty. The wall actually drops down here, allowing everyone to see the shed.

A: It feels like looking down from the top of a wall, a bird’s-eye view.

Cai: Looking from above, you can’t see this. This is also a kind of division. It looks like a bird’s-eye view, but it’s actually a flat surface. This visual effect doesn’t make sense, but it works in a picture book. You can see the trellis dividing the scene, which is also very beautiful. This division doesn’t look dull, and the characters become interesting. You can see the gourd here.

A: This is also the special presentation method of picture books, showing the audience a flat surface, much like a stage.

Cai: On this page (and then two pages), it’s more of a stage effect. The text says, “Meng Jiangnu grew up day by day, becoming a beautiful woman.” So, I used a door as a partition in the painting. Time passes like a fleeting moment. It feels like a thousand years have passed through the crack of the door, right? So, just walking from here to there is already a growth process. It’s completely dramatic and two-dimensional.

A: Although I don’t understand the Japanese on this page, I completely get its meaning. It means to walk slowly and grow up as you walk.

Cai: Yes, partitions are often used in drama. For example, in Romance of the Western Chamber, there are several side rooms separated by doors. This approach is easy to understand, as if there is a fixed meaning behind it.

A: At least Chinese people understand it. Foreigners may not understand it, but Japanese people should understand it.

Cai: Yes, Japanese readers can understand it, and Mr. Nao Matsui particularly likes this painting. I didn’t say anything to him about “time flies”, but he liked it right away.

A: One day we can also find a Westerner to try and see if he can understand this page, haha.

Cai: Haha, it’s really interesting. You see, Meng Jiangnu’s movements remain the same; she’s still a hardworking girl, but her clothes have changed, and so have the things she carries. Her father has aged, and she’s grown up. Some things change, and some things don’t. The house remains the same, but time has changed. I often use this method to depict time, and I also see it in “Mulan.” Going upstairs is a moment, and changing clothes and putting on makeup are also moments. You can see her transformation simultaneously, and the fun lies in these processes. I find it quite engaging.

(Turn to the next page, Meng Jiangnu sees someone in the backyard.) This page also has a stage effect. This person hides here, that person hides there, both visible to the audience. Then the wall is placed there, and beyond the wall are distant mountains, a layer of barriers, coming from that side, as if to emphasize that in this situation, some kind of emotion could arise. This is why they have time to fall in love. If they didn’t have feelings for each other, if they didn’t fall in love, how could they have gone to cry at the Great Wall later?

A: Yes, this is the necessary foreshadowing for this story.

Cai: But this isn’t in the text. It has to be shown in the illustrated story, to establish a solid emotional foundation for them. There has to be emotional foreshadowing. Spaces should be inserted here and there to build foreshadowing, and later on this page (turn two pages back) they should complete their love journey in one single image.

A: In this page, the two people always work together.

Cai: Look, here is the love that was born while we were pounding rice and sifting millet together.

A: These two details have a bit of the meaning of “The Exploitation of the Works of Nature”.

Cai: I first tried drawing water from the well, but I felt the current scene didn’t capture the couple’s affection as well. I moved that to a later page because it didn’t have much to do with the girl washing and drying her clothes. In this later scene (the next page), the girl is a bit shy, stealing glances at him, a bit embarrassed. That’s when I enlarged the flowers.

A: These flowers should have a symbolic meaning.

Cai: Yes, the flowers are blooming, it’s perfect, my heart is blooming too, and I’m in a good mood.

A: Is this flower a peony?

Cai: I have this flower planted upstairs. It’s a redbud. Mine aren’t this red, more rose-red. I like this kind of flower. It’s a bit like a peony, but not quite. Peonies are too rich, while redbuds are more humble, but they have great vitality and a long blooming period. Wan Xiliang also gave her some flowers while carrying water.

A: What kind of flower is this (the flower on the bucket)?

Cai: It doesn’t matter what kind of flower it is, the point is that while carrying water, he didn’t forget to pick flowers for her. Also, in this picture, you can see his parents’ recognition of him.

A: You can see that both elders are very happy and want to arrange something.

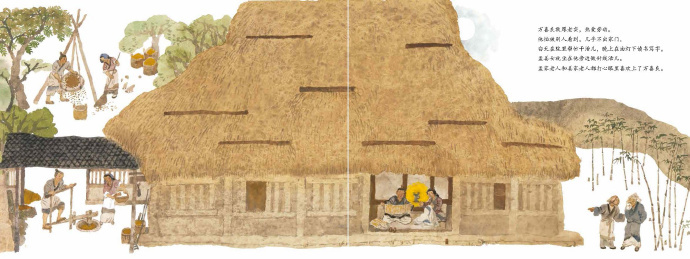

Cai: This is a scene from everyday life, with the parents secretly arranging their marriage. On the next page (the wedding), a stage is separated, and the people in the background are transformed into tiny figures. This allows for more storytelling, eliminating the need for close-ups. Close-ups are usually used to depict psychological events, but that’s not how I directed here. I relied entirely on the story itself, using action to convey the story, much like a play, without relying on close-ups.

A: Chinese people express stories and emotions mainly through the way they do things.

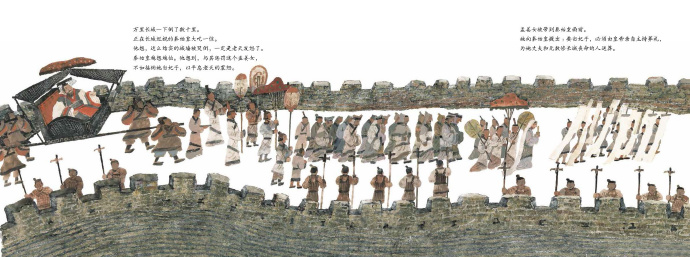

Cai: Exactly. It’s hard to express it if you bring it too close. And this kind of storytelling has to take into account the entire story, especially the later stages. You see, these characters are all “ants,” small-time villains. This book has two main themes: the Great Wall and the storyline. I had to maintain both, developing them in parallel. Why did Naoki Matsui particularly like this book? He said it was excellent, even better than “The Story of Peach Blossom Spring.” I understand why he said I “surpassed” it because, beyond the storyline, there’s also the Great Wall thread running through it, making it even more challenging and, therefore, surpassing my other works.

A: How was the Great Wall line in this book realized?

Cai: My Great Wall came about this way. Look at these lines, appearing here (referring to the painting of the water bearer), they all evoke bricks, the structure of a brick wall. This hasn’t appeared before, and there’s no sense of a city. Here, the Great Wall is hinted at, and it begins to become part of life, and this continues later. There’s a continuous association here, a continuous thread. Formally, the two lines are connected. The beauty of ordinary life at the beginning contrasts sharply with the desolation that follows. With this level of emotional foreshadowing, it would be surprising if she didn’t go looking for her husband. This was necessary, to create the contrast between marriage and the forced labor to build the Great Wall.

A: This house is on both sides of the double-page spread of the wedding and the birth of a son.

Cai: Yes, it also feels like a stage setting, completely oriented towards the reader, guiding the child’s perspective. The child sees the bride and wonders what the people outside are like. This is the kind of joy that only a small village can have.

A: The wedding page brings everyone together to celebrate, which forms the strongest contrast with the next page.

Cai: The atmosphere changes immediately. Then, on the next page, Meng Jiangnu sets out, moving from left to right. The figures below can’t be any bigger. On this page, she’s sewing winter clothes, and the figures are already large enough to show her mood, the change in weather, the rising wind, and her parents’ aging, but she must leave.

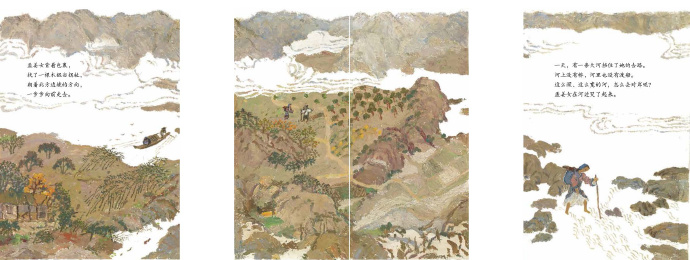

The next page is a triptych, showing the long journey. If it were connected completely, it would be like walking in a painting. The three partitions would tell you about spring, summer, and autumn, walking and walking…

A: This triple partition looks like a screen, but is slightly wider than a screen.

Cai: Yes, it feels like a folding screen. “The Story of Peach Blossom Spring” also has a similar three-panel structure, depicting the vastness of a river. It’s a necessary expression. As you go further down, you seem even smaller, even smaller.

Then comes the crossing of the river on the next page, which reminds me of the story of “Liu Yi’s Letter”.

A: Yes, the story of “Liu Yi’s Letter” is also about the water parting.

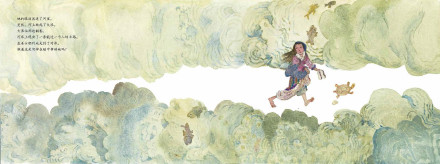

Cai: This is my design; it’s impossible to tell it this way in the text. The original story is that Meng Jiangnu cried and cried, and the water level dropped. How could she move when the water level dropped? How could she express this? Should she float? I didn’t think that would work. I wanted her sincerity to be like Liu Yi’s. The water had to part for her, and once it parted, she could move through. This form feels very good; the water stands up like a wall.

A: You can see fish on the water wall and turtles below.

Cai: Then, with a mixture of fear and determination, she took these steps, with an exaggerated air, walking so fast that her hair flew up. She had to hurry across this vast area, with high water levels. Imagine walking across the riverbed, just imagine what it would feel like if the water stood up. It reminded me of when we went to the underwater world and my grandson said, “Grandma, Grandma, look, the fish are swimming in the sky!” That was very inspiring to me, too.

A: She had to hurry over, and when she got here, the water behind her was almost connected.

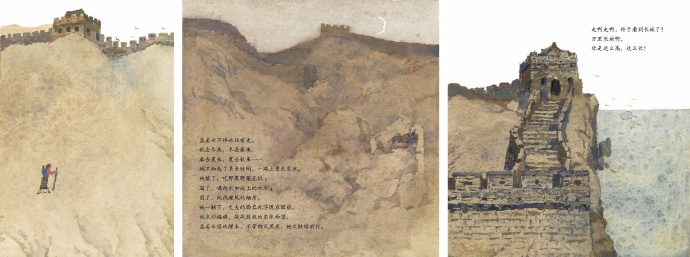

Cai: She looks back and sees the water already pushing her. The scene is tense, creating an atmosphere of fearlessness. She’s very brave. What makes a girl brave? Do you think she’s naturally fearless? Her eyes are filled with fear, yet she’s determined to search. The next page also emphasizes her determination. “The Story of Peach Blossom Spring” is also about searching, that is, searching for an ideal place. This is also about seeking an ideal, but it’s very tragic: she’s searching for her husband. This is even more distant, more uncertain, and more desolate. You have to keep talking about it, using the same method as the Great Wall, with the same distance as the Great Wall. The Great Wall is severed, yet it continues. (Turns to the three-panel Great Wall image) Scenes from different places, just like this, constantly walking, and then resting like this by the Great Wall (under tent and mat on the ground), on a patch of broken grass. I’ve read many ancient musical descriptions of Meng Jiangnu’s personality, including ancient ballads from Hunan Province, and ballads about Meng Jiangnu from every dynasty. Meng Jiangnu is not an isolated case. Every dynasty and generation has had such resentful women, and there have been such people who built the Great Wall. The Great Wall existed in ancient times, and it was completed during the Qin Dynasty, and the gaps were connected in the hands of the Qin Dynasty.

A: It was repaired until the Ming Dynasty.

Cai: The Qin Dynasty built the Great Wall all the way to the sea. Why did I design the Great Wall in the story to the sea? Actually, we have the remains of the Great Wall in Hunan, and it is quite remote.

A: Do you also have Meng Jiangnu and the Great Wall here?

Cai: Yes. There’s the Jiangnu Temple and the Great Wall. I’ve been there, but the Jiangnu Temple was rebuilt later. This is because every dynasty and every country once had a Jiangnu. “Meng” isn’t just a surname; it’s a broader concept. The “Meng” in Meng Jiangnu may be the name of a place. In this story, “Meng” and “Jiang” are two families, but in ancient times, they weren’t. There are so many stories, it’s hard to explain them all at once. I set the story of Meng Jiangnu near the sea, primarily to create a grand scale that would complement the Great Wall. So I had to depict the sea. Once we reach the beach, I don’t need to draw the characters; I’ll leave it to the reader’s imagination.

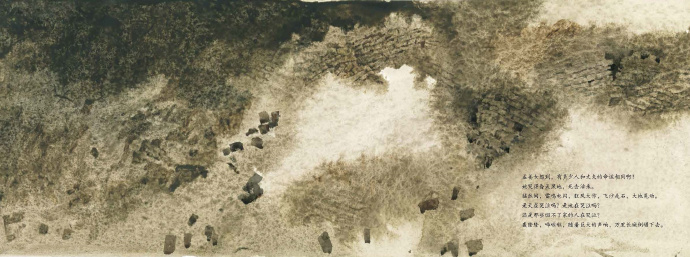

A: In this picture of her resting by the Great Wall, the figures are very blurry, and there is a crescent moon on the Great Wall.

Cai: There’s a caption here. Based on the scene and the text, you can imagine how she slept in this situation. That’s actually a good thing. Then you see the desolation of the ancient Great Wall (flip to the next page), its broken, damaged appearance before repairs. The collapse is beautiful, a sense of vicissitudes.

A: Many parts of the Great Wall look like this now.

Cai: Yes, it’s still incomplete. I drew it this way based on photos I found. I can’t travel around much anymore.

A: I’ve visited many ruined sections of the wild Great Wall. Many places are still quite dangerous. They’re very high and steep, making it easy to fall, and even get struck during thunderstorms. This image of the ruined Great Wall gave me a similar feeling.

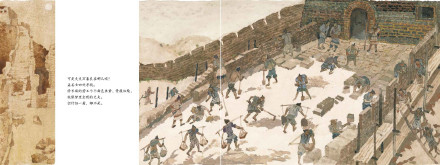

Cai: I like this sense of vicissitudes. It also lets readers know that the Great Wall needed repairs at the time, connecting it to the subsequent story. We need to understand that the Great Wall was built and repaired in this way, so this painting of the construction of the Great Wall was also necessary. I also consulted a lot of materials to complete this painting of the construction scenes and the construction of the Great Wall. Then I placed Jiang Nu in this place (on the left side of the picture).

A: She walked slowly from the left and then walked out from the other side.

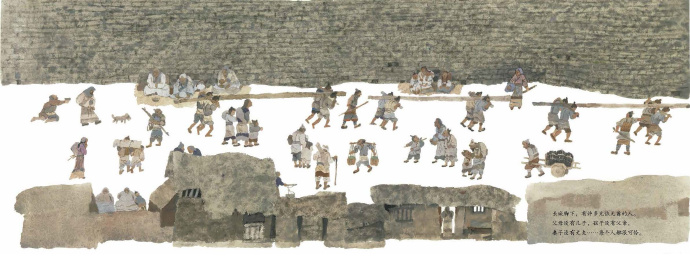

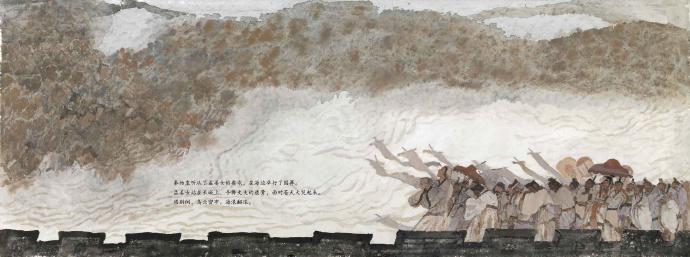

Cai: She searched all the way, it was such a arduous search. Then she came to this place (turn to the next page). I had to paint this place: the roots of the Great Wall, because her husband was buried there after his death. This place was also a slum, filled with people in need, all looking for their husbands and relatives. She followed these people, the people who built the Great Wall.

A: She first appeared at the lower left, then at the upper right, and walked along the foot of the Great Wall.

Cai: She kept walking, seeing all these people, and none of them were her husband. Then she moved on to the next page, to a more grand scene, which she had to see as well. As she continued to look along, she finally understood how the Great Wall was built; it was a massive construction site.

A: These paintings are very good. They are schematic diagrams of the construction and repair of the Great Wall.

Cai: I painted these paintings with great care and detail, and I did them at least twice. Doing them twice or more isn’t easy. I’ll show you my first draft later. The painting is much better now, with a stronger overall feel and excellent technically. These little figures look amazing after the second pass! Although small, every detail is clear. The charcoal seller is here (to the right of the painting at the foot of the Great Wall). It’s meant to evoke a connection. Although this isn’t the charcoal seller, it’s the same concept. Look, over here are orphans and widows, while over there are the able-bodied men. Over here are the homeless, searching for their loved ones.

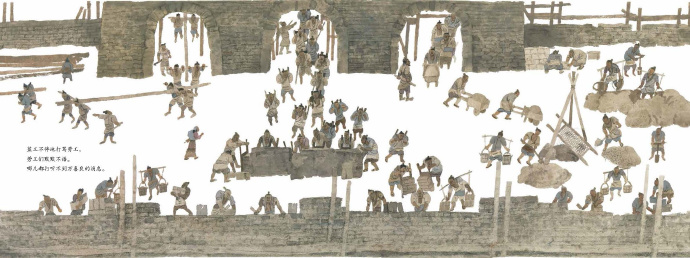

A: The next page shows scenes of construction on a construction site, showing various construction activities. In contrast, the previous pages are scenes of daily life.

Cai: Yes, both everyday and architectural scenes are necessary. I looked up information on how ancient people pushed carts. I visited construction sites, and everything else is based on assumptions. The architectural aspects are similar, and the techniques are similar.

A: Then the scene of carrying bricks on the next page seems to have a strong symbolic color.

Cai: It’s symbolic. The life of an ant, like an ant, carries a heavy burden. They approach Jiang Nu, and even though they’re face to face, it’s hard to tell who’s who, to identify their husband. It’s like Leo’s search for the prince in Swan Lake. The identification in that ballet is beautiful, while here it’s truly tragic. All of these men could be her husband, or none of them. It’s like, “A thousand sails have passed, but none of them is the right one.” That’s the feeling. I wanted to paint this: a girl standing here, dressed in rags, representing the many Meng Jiang Nus searching for their husbands, each of these strong men who may or may not be their husbands.

A: The black here is very thick and large, almost too large, and has a strong sense of symbolism.

Cai: The sense of oppression is particularly strong, indeed, quite excessive. It’s approaching its most tragic moment, on the verge of exploding. Just look at how heavy it is. I wanted to emphasize the weight of black here, to emphasize the growing pressure on her heart. She feels so hopeless, so hopeless, so near the end, so lost. Then someone tells her, “Your husband is over there, buried somewhere.” Only then does she receive the true news.

A: At this time, she has to turn her back to us.

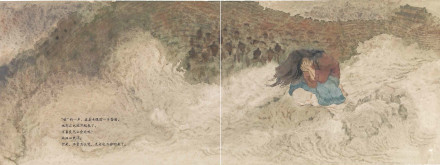

Cai: Yes, we can’t see her face. Without it, it’s difficult to express, so I can only use my body language. She’s about to fall. She can’t stand up, her legs give out. And so, she kneels down. She hasn’t weakened at all along the way, but here, she’s about to fall. Here (turn to the next page), at the foot of the Great Wall, she must fall. She cries, and I can only depict this gesture here: the gesture of weeping. And speaking of her crying, I wonder where the power of the Great Wall lies. It’s a completely supernatural force, a spiritual force, I understand. Its soul has emerged. Her cry, every brick is moved. A British writer said that beneath every railroad tie lies the soul of an Irish worker. In our old spinning mill, every spindle held the soul of a wronged Chinese girl. I painted souls, each brick a ghost of a strong man. This is the Great Wall of flesh and blood. So, her earth-shaking cry, like a storm, surges and clouds, arrives just like that.

(Turns to the next page) The Great Wall at this point is an image, not a realistic one; it’s a feeling. This painting wasn’t easy; I worked on it several times. The previous one was also difficult; I painted several different crying poses. There was only one way, crying with hands raised, the kind of crying that can’t be helped, the tearing cry, the crying of kneeling, clinging to her husband’s clothes. And then on the next page, she’s gone. The Great Wall has collapsed, a gap has appeared. Needless to say, this one turned out incredibly well; I couldn’t have imagined it would be so. I tried several times, and when the mood struck, I felt confident. I said, “It’s coming, it’s coming,” and it just happened. The atmosphere was wonderful, like a landslide.

A: This should be the climax.

Cai: Yes, there are no people here, only an image, a whole. Meng Jiangnu has also collapsed, having reunited with her husband, their two spirits have merged. But there is also a tail, and it cannot be left out because the story must continue.

(Turn to the next page) The Great Wall continues to appear, with a solemn sacrificial scene. Meng Jiangnu requested a state funeral for her husband, and I thought of a national mourning, with all the world in mourning. The literati, also feeling uneasy, wanted to join the sacrificial ceremony to appease the public anger. I also felt it was a good idea to add a stroke here. The power had to be lowered here; Qin Shihuang and the literati were required to attend, so I drew a ceremonial procession. I drew Meng Jiangnu in the foreground, far ahead, her reckless defiance reminding us of her majesty. This flow of thought leads to the final stroke. (Turn to the next page) As she weeps, the real Great Wall, the flesh-and-blood Great Wall, appears, so I drew this stroke. This stroke is essential; it further clarifies the concept of the flesh-and-blood Great Wall.

A: The one below where people are standing is the realistic Great Wall, and the one above is the Great Wall of the soul.

Cai: The Great Wall of the Chinese Spirit. Several factors come into play, and then there’s the wind and clouds, which can be interpreted as any sudden, unpredictable, and unforeseen event. So, amidst all this, there’s the final act of utter disgrace. The common people saw Meng Jiangnu throw herself into the river, but I painted it as Meng Jiangnu throwing herself into the sea. My son wasn’t satisfied with this final painting, and I wasn’t satisfied either. So he extended the image to one side, opening up the sea and placing the figure in the center. Then, like before, he placed the figure in the river, opening and closing it again, as if giving the sea emotion.

A: Maybe the sea also protected her.

Cai: It’s like Jingwei filling the sea, with that spirit, and Meng Jiangnu’s heroic spirit, with that sense of dying in glory. So I painted the sea to resemble jade, with a sense of beauty, not fear. It’s not a black sea.

A: Here, the colors become bright again.

Cai: Let’s go back to the painting of crossing the river. It’s also green, and it has a jade-like feel. This is my interpretation of water throughout the entire painting. There’s a connection between the two pages. You see, rivers, lakes, and seas, I see them as one thing. Jade, I see it as a kind of meteorite, and I want to paint it preciously and beautifully. You see, Meng Jiangnu, who jumped into the sea, didn’t look very tragic. I painted her as if she were about to fall asleep, holding her husband’s hand.bone china, just jump like that.

So, as you said, this book is more like a drama in structure. Unlike “Bao Er,” which is more psychological, with that strong folk, strange, and spooky atmosphere, that book had to be written in black throughout, to have a spooky vibe. “Meng Jiang Nu” is different. It doesn’t have a spooky vibe. It must develop naturally to its climax like a normal story, with the integrity of a drama from beginning to end.

A: I’d like to ask you a question. In the penultimate painting, the one that summons the spirit, Meng Jiangnu is facing left, toward the “back,” while the preceding story unfolds toward the right. Is there any special significance here?

Cai: This is mainly about power. The front is always facing right, but here we need to face left, so the power is gathered and prevented from escaping. These souls are gathered here, and this curve resonates with her, connecting her. From another angle, she can be seen like this. Because the Great Wall ends here, it ends here.

A: So here we are looking back, those souls came from the Great Wall.

Cai: Look at the Great Wall I drew. It swirls around like this, breaking off like this. If it came from this side, it wouldn’t be finished on the other side. But now it feels like it’s advancing, pushing from left to right.

A: So Qin Shi Huang became very frightened and lost his composure here.

Cai: At this point, he also felt the might of Heaven and showed his weakness before the heavens and the earth. The Son of Heaven, the Son of Heaven, was also subject to Heaven’s control. He could not, no matter what, anger Heaven and Earth. Therefore, in the original story, his decision to marry Meng Jiangnu was also a soothing act. He married her, and she found a good home. The original story goes like this. He said, “How can I blame you? This is my fault.” Meng Jiangnu replied, “How can I blame the Son of Heaven? Just as war is inevitable, so is building the Great Wall.” She said, “I only regret one thing.” Qin Shi Huang asked her what it was. She replied, “If only I had been born a decade earlier or later. I only blame myself for being born at the wrong time.” So pitiful! I was deeply moved when I saw this. Many people truly don’t blame Heaven or others. The Chinese are known for their loyalty and honesty. They simply feel they were born at the wrong time. I don’t blame your power; he didn’t have that kind of power. He also knew that the Emperor’s fate was irreversible. I can only blame myself for not being born a decade earlier or later. Seeing this, I can’t describe the feeling in my heart. It’s so heavy! So pitiful! This is how it was in the surging river of history, and it seems to remain so even now. Many intellectuals, like Wang Bo, who said, “How could a child know, witnessing a triumphant feast?” They have a kind of awe within them, and this also applies to the unknowable, including power.

This can also be considered a kind of insight, a woman’s insight. Like Hua Mulan’s, it all clicks here. Why did Hua Mulan join the army? It was because she knew war was inevitable. It was a natural and man-made disaster, and there was no point blaming anyone else. Ultimately, it was better to face it herself. Meng Jiangnu’s response was to search for her husband, but when she couldn’t find him, she longed to see him one last time, even to see his remains. This kind of emotion requires a final encounter, only then can it be fulfilled. Even this final outcome is a kind of fulfillment, to be with him. This is something that has been passed down since ancient times. I say that the Chinese are truly loyal and honest.

A: So from your understanding, this search for a husband is more like a symbol.

Cai: Yes, it’s more like a symbol. The weight of the story is too great, and my pen can’t carry it. When I’m forced to read these historical stories, I don’t really judge these two plot lines in any way. The Great Wall was inevitable, Meng Jiangnu was inevitable, its collapse was inevitable, its restoration was inevitable, and people’s love for it is inevitable. This subject matter daunts me, and I know that maintaining these two plot lines is a real challenge in terms of form.

…

Argentine Primera División (According to the recording) on May 20, 2016