The idea for this book first came to me when I was translating Dear Genius: The Letters of Ursula Nordstrom. It took two and a half years, and with the combined efforts of everyone involved, to finally complete it. This book follows the characters introduced in Dear Genius, telling their life stories one by one, in chronological order. Threading these stories together, a breathtaking picture emerges: a vast cross-section of the American children’s book landscape for roughly half a century after the 1930s! While not complete, it provides a glimpse into the broader picture.

A long scroll made of letters

“Dear Genius” is a collection of nearly 300 letters written by Ursula, a brilliant American children’s book editor, to authors, artists, critics, and readers. These letters were selected from over 100,000 letters surviving from her nearly half-century career. These authors and artists are many of the most celebrated talents in the American (and international) children’s book world. Many of them have become increasingly familiar to Chinese readers and have countless fans there. Many of the works discussed in these letters have gone on to become classics of children’s literature worldwide. Readers who love children and children’s books often yearn to understand the stories behind these wonderful books, while children’s literature enthusiasts and researchers also seek to understand the creators and the context behind their creations. Ursula’s letters are truly a rare first-hand resource.

However, simply reading the collection of letters is inevitably confusing: if one doesn’t know much about the recipients, understanding their content can be difficult. And because copyright and other issues limit the collection to single-sided correspondence, a comprehensive understanding of the topics discussed can be challenging. Therefore, these letters may initially appear to be scattered fragments. But with enough patience, putting these “fragments” into a coherent order, searching for more relevant information to transform them into clearly defined, fleshed-out characters and stories, and employing a bit of detective work to uncover the connections between them, a seemingly complete scroll gradually emerges. And Ursula is precisely the scroll of this scroll.

Early childhood reading promotion campaigns in the United States

To fully appreciate this long scroll, one needs to have a basic understanding of the progress of children’s reading promotion in the United States in the early 20th century. While the United States is now a clear superpower in the children’s book sector, in the early 20th century, it was a mere follower of Europe (particularly Britain), and piracy was rampant. Beatrix Potter’s The Tale of Peter Rabbit, hailed as “the pioneering work of the modern picture book,” was published in Britain in 1902, and pirated copies appeared in the United States just two years later! However, within this rising power, a thriving movement was underway that significantly propelled the development of American children’s books, gradually propelling them to the forefront of the world. This movement was the American Children’s Library Movement, or, in modern parlance, the American Children’s Reading Promotion Movement.

This book introduces this movement through the story of the legendary children’s librarian Virginia Haviland. Haviland can be considered a third-generation promoter. Anne Carroll Moore, the often-mentioned head of the children’s book department at the New York Public Library, and Haviland’s mentor, Alice Jordan of the Boston Public Library, can be considered second-generation standard-bearers. Thanks to this movement, the United States began establishing dedicated children’s reading rooms in public libraries in the early 20th century. Librarians and community members often read children’s books aloud to children as a primary means of promoting reading. As early as 1902, the Boston Public Library had a dedicated storyteller. Later, Miss Porter expressed her envy of this in a letter to Ms. Moore, as Britain was still quite conservative in this regard.

Precisely because of this increasingly vigorous promotion, society’s demand for children’s books (especially trendy children’s books) grew, prompting major publishing houses to establish dedicated children’s book departments. In 1919, the world’s first children’s book editorial department was established at Macmillan USA. Founding editor Louise Bechtel was only 25 years old, having graduated from the prestigious Vassar College only a few years earlier. Subsequently, companies like Doubleday, Viking, and Harper’s also established children’s book departments. In 1919, Ms. Moore, Mr. Matthews of the Boy Scouts of America, and Mr. Melcher, editor-in-chief of Publishers Weekly, jointly launched the first Children’s Book Week. A few years later, also at Melcher’s initiative and sponsorship, the American Library Association’s Children’s Library Section established the Newbery Medal. In 1922, 212 librarian representatives voted for the first winner, The Story of Mankind. With such continuous promotion, “A Million Cats” created by native American artist Wanda Geiger was published in 1928. This work made children’s librarians represented by Moore particularly proud, because it can be said to be the first world-class original local picture book in the United States — the soil cultivated for a long time finally bore fruit.

Greenwich Village

Ursula entered the scene in the early 1930s. Initially a shy clerk in the college textbook department of Harper & Company, she transitioned to the children’s department a few years later and quickly found her place in the role that would ultimately become a groundbreaking editor in American children’s publishing. During these early years, she primarily lived in Greenwich Village.

Greenwich Village in Lower Manhattan, New York is a place mentioned in many stories in this book. We will see that: William Pene du Bois and Kara Kuskin grew up in this area; Ezra Jack Keates’s father worked as a waiter in a cafe here, and lied to little Keates that he had exchanged soup for paint from a down-and-out artist; Marco Semon and Robert McCloskey raised ducks in the bathtub of the apartment they shared here, and they later became the models for “Make Way for Ducklings”; Margaret Wise Brown studied early childhood education here and became a writer. She also bought a small stand-alone building here as a studio, and completed classic picture books such as “The Runaway Bunny” and “Goodnight Moon” here; Margaret and Ursula often met at a cafe on a corner at breakfast time. The area was once a hub for conversation; Clement Hurd, Leonard Weisgaard, Maurice Sendak, and Tommy Unger all lived here. Sendak and Unger had similar schedules and often met for chats at mealtimes. HA and Margaret Ray lived here before moving to Boston. Seeing Ursula lonely, Mrs. Ray even brought her a puppy. It was here that Mr. Ray completed his book, “Stellar: A New Way of Seeing the Sky,” observing the sky from the rooftop of a six-story apartment building. EB and Katherine White also lived here in New York, and Charlotte Zolotov rented here with her husband when they were newly married. It was once a hub for writers, artists, and radicals and alternative figures (including homosexuals). Even today, despite its transformation from a neighborhood of tenement buildings to a high-end residential area with exorbitant land prices, many in the arts still prefer to live there.

Looking back at Greenwich Village before the 1970s, it felt like a truly symbolic village (even though it was essentially made up of reinforced concrete blocks). Everyone in the village seemed to know each other and had harmonious relationships, yet everyone was keen to go their own way, especially to be different. Many landmark works in the history of American children’s literature were conceived or spawned there.

From Bank Street to Fifth Avenue

In Greenwich Village, there is a small street called Bank Street, which is actually a small street between West 11th Street and West 12th Street. It was named after the Bank of New York, which once stood on this street. But what really made this street world-famous was the Bank Street School of Education, an experimental early childhood education institution that was established there.

Fifth Avenue, a major north-south thoroughfare in Manhattan, New York, is often associated with extreme luxury, as many of the world’s luxury boutiques are clustered there. However, in the heart of this prime location, there are surprisingly two libraries: the New York Public Library and its Manhattan branch.

The distance from the former site of the Bank Street School of Education to the New York Public Library is about 3 kilometers, or a 40-minute walk, which is quite close in a metropolis like New York. However, in the first half of the 20th century, the two became almost mortal enemies in the field of children’s books.

The standard-bearer of Bank Street School of Education is the school’s founder, Lucy Mitchell, who was Margaret Wise Brown’s mentor. At the same time as she founded the school, she also founded an experimental kindergarten. Later, she encouraged a parent of a kindergarten child to establish Scott Company, which mainly published works for members of the “Here and Now” creative experimental group, and Margaret was the founding editor and leading writer.

The standard-bearer of the library camp was the aforementioned Ms. Moore, who once played a crucial role in promoting children’s reading. However, in terms of her reading interests, she preferred traditional classics and fairy tales embodying the elegance of the Victorian era. She disliked realistic and unconventional works and was averse to incorporating modern art into children’s books. She was deeply opposed to Mitchell’s “here and now” writing philosophy, which emphasized the experience of contemporary life, and naturally disliked Margaret. In her later years, Ms. Moore became even more intolerant, disliking neither the “Little House” series nor “Charlotte’s Web.” Due to her immense influence in the children’s library community, works she disliked often missed out on major awards and were even excluded from public library recommendations, significantly impacting their promotion and sales.

Although Margaret was Michel’s most prized protégé and assistant, her unique poetic temperament and literary sensitivity enabled her to surpass (and, to a certain extent, betray) her mentor. Her most successful works embody the concept of “here and now” while also retaining a poetic fantasy and fairytale-like charm. Ursula, born the same year as Margaret, was three months older, but she idolized her and was deeply influenced by her children’s book writing and editing philosophies. They shared a love of modern art, which emphasized free expression, and naturally gathered around artists like Hurd and Weisgaard. Despite Margaret’s untimely death, the influence of the experimental creative community at Bank Street College of Education continued to ferment and expand. Its successor, Ruth Kraus, teamed up with her husband, the left-wing artist Kroger Johnson, and with the emerging Maurice Sendak, they produced a series of revolutionary works that were quite revolutionary for the era.

Fortunately, by then, the children’s library and children’s literature criticism communities were gradually opening up. We saw prominent critics like Lindquist, editor-in-chief of Horn Books magazine; Haviland, editor-in-chief of the Children’s Book Center Newsletter; and George Woods, editor-in-chief of the children’s section of The New York Times Book Review, all aligning themselves with the reformist movement represented by Ursula and others. More and more children’s librarians were re-evaluating their previous judgments and gradually revising them in various ways. Although they failed to award a major prize to any of the “Little House” books, they eventually established a new lifetime achievement award for their creators—the Laura Ingalls Wilder Medal, which they later gave to E.B. White, author of “Charlotte’s Web.” In 1964, they even awarded the Caldecott Medal to the controversial “Where the Wild Things Are” upon its release. Even Sendak later said, “That was perhaps the most surprising thing in my entire life.”

Before the curtain of history

The 61 individuals featured in this book are cultural elites active in the American children’s book industry since the 1930s. They are all considered heavyweights in terms of their achievements and status. Let’s examine their composition using a set of data.

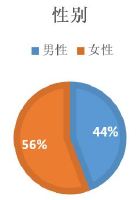

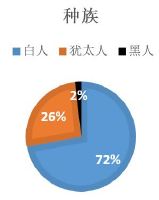

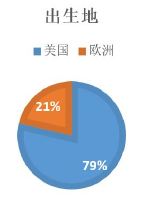

Of these, 34 were women, a slight majority. Considering that children’s book editors (such as Ursula and Susan Hirschman) and children’s librarians at that time were all women, the gender ratio among children’s book creators was roughly 50–50. In terms of birthplace, over 20% of the creators were born in Europe, a characteristic of the United States as a nation of immigrants. In terms of ethnicity, Jewish people made up over a quarter of the creators. What explains this?

Let’s try to place these geniuses in the children’s book world in the context of American history.

Let’s start with Laura Ingalls Wilder. She grew up amidst the American westward expansion of the mid-to-late 19th century. Janet Sperling Lowry and Fred Gibson also experienced similar pioneering family life. However, you’ll notice that Wilder’s “Log Cabin” series appeared after 1932, during the height of the Great Depression. It was precisely at this time that such stories resonated widely.

From the mid-to-late 19th century to the early 20th century, the United States experienced several large-scale waves of immigration, with European Jews being the most prominent. While some immigrants were relatively affluent German and Austrian Jews, such as the ancestors of Ruth Kraus and Mary Rogers, many were impoverished Jews from Eastern Europe and Russia, including the fathers of Ezra Jack Kitz, Maurice Sendak, Nat Hentoff, and Shel Silverstein. These impoverished Jews primarily clustered in the slums of Lower Manhattan and Brooklyn in New York City, later dispersing to cities like Boston and Chicago. The two world wars, fought primarily in Europe, drove a significant number of European cultural elites across the ocean to the United States. Figures like Isaac Singer, H.A. and Margaret Ray, Maya Wojciechowska, and Leo Lionni fled to the United States. After the wars, figures like Tommy Unger, Eric Carle, and Anita Lobel, who had endured the hardships of war, immigrated to the United States. Although the two world wars and the Great Depression in between brought great economic impact to the United States, they actually provided excellent development opportunities for this large immigrant country, even in the field of children’s books.

During the early Cold War following World War II, the political atmosphere in the United States was extremely tense. McCarthyism was rampant, and many left-wing writers were persecuted, unable to publish or teach normally. In other words, their livelihoods were almost cut off. Fortunately, however, censorship in the children’s book industry was less strict, and with the help of free-spirited and fearless editors like Ursula, a group of left-wing writers such as Johnson Kroger and Millicent E. Selsom were attracted to the children’s book industry. Perhaps we owe some of the incredible talent of children’s books like “Arrow Has a Colored Pen” to the rampant McCarthyism.

The 1960s marked perhaps the most tumultuous chapter in American history: the Civil Rights Movement, the Vietnam War and the anti-war movement, the assassinations of President Kennedy and Martin Luther King, the women’s movement, sexual liberation, and gay and lesbian violence against police… Interestingly, many landmark works in the children’s book world were also produced during this decade. For example, “The Snow Day,” the first picture book featuring a black child, won the 1963 Caldecott Medal. In 1969, the less-than-19-year-old black artist John Steptoe published his acclaimed picture book debut, “Steve.” That same year, the first juvenile novel to address the topic of homosexuality, “Arriving: A Trip Worth the Journey,” was published.

None of this is accidental. When we place the paths of these geniuses on the backdrop of history, everything seems natural.

Maverick geniuses

However, while it is said that heroes are made by the times—that special figures always emerge in certain eras—why did these particular individuals emerge? There must be some mystery involved.

In this book, we’ve compiled a resume for each genius, assuming they were looking for a job. Imagined, it would be a portfolio of impressive experiences. But in reality, most of these individuals’ resumes, judging solely by their family background, education, and work experience, are largely unremarkable. On the job market, they’d be nothing more than a potential office clerk or graphic designer. For example, H.A. Ray dropped out of college, and his primary job experience was selling bathtubs. Sendak only had a high school diploma, attended a few night art classes, and his primary job experience was decorating windows in a toy store. Silverstein struggled in college, drew comics while in the military, and initially ran a hot dog stand after his discharge. EB White, despite attending the prestigious Cornell University, changed jobs at least five times within four years of graduation, either quitting or being fired. In short, before reaching their peak in life, most of these individuals experienced similarly chaotic lives, some even struggling to make ends meet for nearly half their lives. Yet, they all ultimately surpassed themselves. What’s the secret?

In a letter to Sendak dated January 31, 1963, Ursula let slip a few secrets: “You are not the ‘difficult genius.’ First of all, geniuses are naturally difficult…” Coming from someone who dealt with this crowd constantly, this statement seemed quite plausible. Yet, in the eyes of Susan Hirschman, another talented editor, only Ursula truly deserved the title of genius because she was, in fact, difficult. It was Ursula who fired Susan from Harper’s! This “difficulty” was actually a state of eccentricity, which, to others, seemed like a self-willed habit.

While these “geniuses” are at the top of the children’s book world, their works captivating and captivating, captivating countless children worldwide, they almost all possess a few “quirks,” and the greater their achievements, the more pronounced their quirks. Of course, the “quirks” mentioned here simply describe their uniqueness. Some of these “quirks” are, from any perspective, perfectly healthy. For example, Roland, a pioneer farmer, constantly wrote in his spare time, a habit of writing that can be considered a virtue. Similarly, M.E. Kerr’s penchant for self-given pseudonyms, which stemmed from simple financial necessity, has gradually become a cherished virtue. However, when these “quirks” reach deeper levels, challenging the stubborn ethics of their societies, they often become embroiled in conflict and controversy. This is precisely the most intriguing aspect of the stories of these geniuses: landmark works often emerge from controversy, and when they ultimately overcome it, they emerge stronger and more powerful.

In the words of the restless Eva Golian: “People who are naturally gentle, calm, and don’t cause trouble, who always stay away from violent emotions and evil temptations — people who have never had to fight side by side with angels at night and win with a limp until dawn — these people can never become great saints.”

Growth in various forms

Everyone who participated in compiling the information and writing the stories of these geniuses in this book is a parent. We can’t help but want to explore their growth paths in the hope of learning from them.

Overall, the paths of these geniuses’ development vary widely. Some came from well-off families, but those raised in such privileged circumstances seem more prone to rebellion, such as Clement Hurd and Mary Rogers. Others, like Ezra Jack Keates, came from relatively difficult backgrounds but nonetheless developed resilience, a skill that was evident in their upbringing. Overall, however, the economic circumstances of these geniuses varied widely, with more affluent families tending to have a stronger artistic atmosphere, while less affluent families appear to have closer relationships. We often see that in less affluent families, the bonds between siblings are often stronger. While parents may be unable to care for their children due to financial difficulties, the influence they exert on each other is immeasurable. The influence and support of their brothers played a crucial role in the development of individuals like Singer, Syd, White, Gibson, DeJong, and Keates.

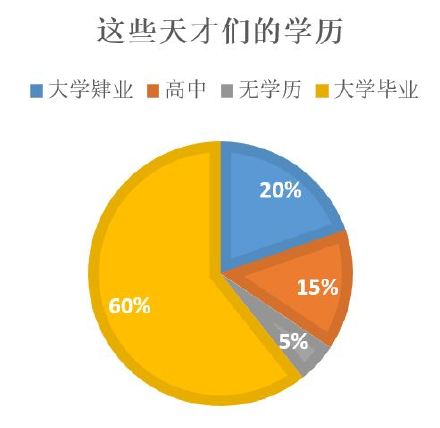

As mentioned above, their educational background reveals that only 60% of this group completed college, 20% attended college but did not graduate, and another 20% either completed high school or had unknown educational backgrounds. Of those who graduated, only seven went on to obtain a master’s degree or a dual degree. Of these, only one was male: Mr. Donovan, who completed his Master of Laws, but he later changed careers. Nearly 60% of these graduates were women, perhaps because, in their era, women seeking to make a living were more reliant on a college degree. However, for the vast majority of these individuals, the majors they studied in college often differed significantly from the successful careers they ultimately pursued. Their career success is largely due to interests and habits cultivated from childhood, primarily drawing and reading in the field of children’s books. If there was one common thread growing up, it was reading. Regardless of their family backgrounds, they all shared a passion for reading from a young age. Those who have a penchant for art often develop a habit of constantly painting from a young age. For example, HA Lei, who traveled to the Amazon Basin in Brazil to sell bathtubs, sketched monkeys along the way. It would be strange if such people didn’t become painters.

Another point worth noting is that, regardless of whether or not the childhoods of these children’s book geniuses can be interpreted as happy, they were undoubtedly memorable, and their childhood memories are an inexhaustible source of wealth for their creations. Moreover, even those whose childhoods were less than commendable were always surrounded by those who loved them deeply, nurturing and encouraging them. The power of love is more conducive to growth than material comforts. The most enviable childhoods are often those spent in close proximity to nature, on the prairies, on farms, in the mountains, by rivers, lakes, and the sea, either settled in their homes or on extended vacations. Such a growth environment, accompanied by a good education and warm family affection, is how geniuses like Roland Ingalls Wilder and E.B. White were nurtured.

Success and happiness

When discussing a piece of literary history, people often focus on the work’s value, the author’s contribution, and their place in literary history. Few ask: Were the authors happy? Does reading their works bring happiness to readers? Such questions seem to have no historical value, or perhaps even impossible to answer. However, when discussing children’s books, such questions seem particularly relevant: Was the author of “Charlotte’s Web” happy? Does reading “Charlotte’s Web” bring happiness to readers (primarily children)? If you love children and cherish childhood, how could you possibly not be concerned with such questions?

When compiling the stories of these geniuses, we paid special attention to this question. While it’s impossible to interview each of them individually, let alone ask them, “Are you happy?” However, through reading their autobiographies, biographies, and interviews, consuming relevant audiovisual materials, and observing their actions, I’ve found that, as a creative group, successful children’s book writers are perhaps the happiest of all literary creative groups. There may be one or two exceptions, but nearly all children’s book writers are deeply satisfied with their readers. Their stories may contain intense conflicts and reveal the darker sides of human nature, but they almost always end with a fairytale promise: they will live happily ever after… And those who are particularly sincere don’t see such promises as a temporary coaxing, but sincerely seek solutions, comforting their young readers while also healing their own wounds. As Hayao Kawai discovered in “A Child’s Universe,” childhood holds a powerful power that not only helps children but also greatly helps adults.

Maurice Sendak was perhaps one of the geniuses who most profoundly discovered this secret. His lifelong work seemed to be a form of healing, particularly addressing the deep trauma of fear he endured growing up. Nearing his 80s, his partner of over half a century was nearing death. He stayed by her side in the hospital room, himself ill in another. The loneliness, helplessness, and grief he felt were unimaginable to others. During this time, he conceived a new picture book. After his partner’s passing, he plunged into his work, finally publishing it at the age of 83 (a year before his death). It was “Adi the Pig,” perhaps the most lighthearted and cheerful of Sendak’s picture books. Despite being born into a deeply Orthodox Jewish family, Sendak was not religious. He said he envied those who believed, because life in this world without faith was bound to be much more difficult. Yet, he ultimately persevered, living a fulfilling life with few regrets, perhaps because he found his own way to pray—writing children’s books for children and for himself.

For those geniuses who create children’s books, when their success is based on a perfect connection with childhood, it must be an indescribable happiness.

Ajia …

Written in Beijing on April 23, 2015