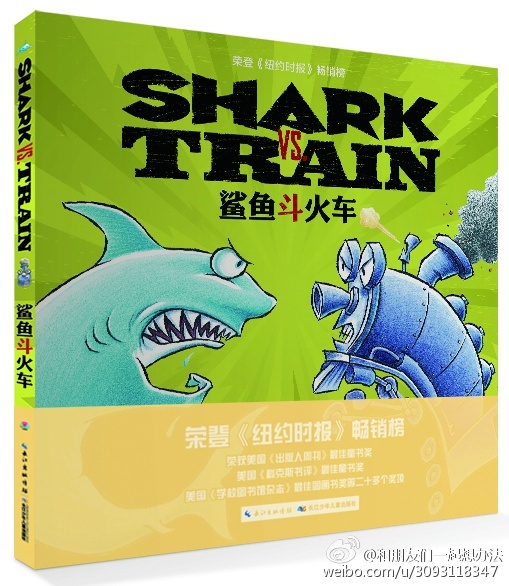

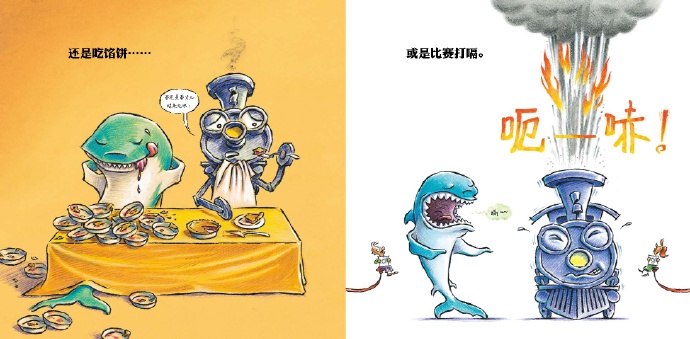

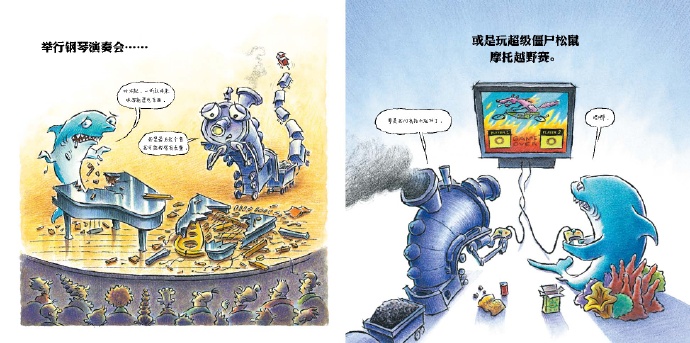

Have you ever heard of a shark vs. a train? How is it fought? Ping-pong, poker, high diving, slam dunk contests, piano playing, burping… It sounds like a complete mess, even more chaotic than the crosstalk story of “Guan Gong vs. Qin Qiong.” But there really is a picture book called “Shark vs. Train,” which made the New York Times bestseller list and has been a hit across the United States.20Such absurd yet amusing things can only happen in the world of children’s books.

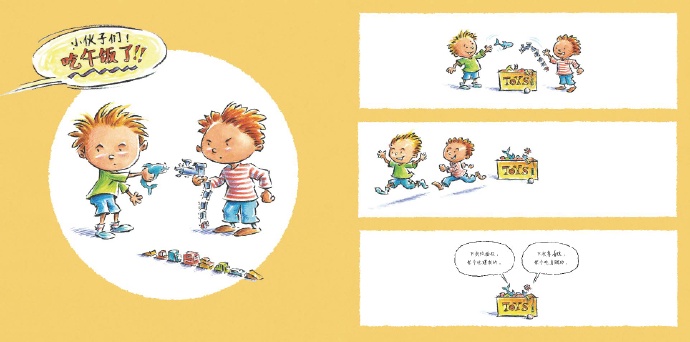

Open this seemingly boisterous book, and don’t rush to the title page. Instead, look at the story already begun in the endpapers. Then, wandering through the illustrations until you reach the final pages, you’ll discover: Oh, this is actually a story that makes perfect sense. Two boys in the book grab their favorite toys—a shark and a train—from a pile of toys. One pretends to be a shark, the other a train, and they engage in a fierce, imaginary battle. The competition escalates, and the atmosphere heats up—until… lunchtime arrives, and the shark and train return to their toy box. It turns out that the book’s endless stream of seemingly intense yet absurd battles are nothing more than the product of a child’s imagination.

But this is just my adult interpretation. Reading this book with children, especially those who love trains, cars, weapons, and menacing dolls, will surely be a completely different experience. They might take it seriously, immersing themselves in the story with great enthusiasm. They might even build on the existing situation and create even more thrilling scenarios, unfolding a more exciting story. This reminds me of the mock war games I often played as a child: chess pieces and military flags were placed on the bed, divided into “our army” and “the enemy army.” Pillows and quilts were used to simulate the terrain, and various stationery items were used to simulate fortifications and weapons. Despite the rudiments of the conditions, after each battle, the pride of “our army” when they successfully annihilated the stubborn resistance of the “enemy” was no less than that of the general who orchestrated the battle.

Perhaps every generation has played this kind of “boring” game. When Chris Barton was a child, he played “Big Jim”, which is an American70back,80The little action figures that our children once loved were essentially the muscular men from action cartoons, punching and kicking, fighting off evil (perhaps even villains), looking very sexy and indestructible. Boys, in particular, loved to playfully fight with these figures. Mr. Barton now has two sons, each fascinated by sharks and trains. While the objects are different, the tradition of pretend fighting in their imaginary worlds has endured, and as a result, their fights have become the stories in their father’s picture books.

I believe both Chris Barton and illustrator Tom Lichtenhold have a deep understanding of this tradition, not least because it’s part of their childhood memories. Tom said in an interview, “I believe it’s crucial for children to understand that their imaginations are not only novel and fun, but also possess real value.” In fact, long ago, Lu Xun also lamented the value of this imagination: “Children are worthy of respect!” Therefore, creating books for children is no easy task; it requires understanding and respect, while also providing opportunities for their imaginations to flourish freely.

Tom has a masterful knack for capturing children’s imaginations. His illustrations for “Goodnight, Workshop Trucks” blend beloved trucks with heartwarming goodnight stories. Meanwhile, “Train Dreams” transforms children’s imaginative play with train toys and various dolls into a bedtime story that’s both absurd and riotous, yet also evokes a sense of dreamlike wonder. These hilarious scenes recall the work of Dr. Seuss, while the wondrous interplay between the imaginary and the real worlds evokes the wonders of Margaret Wise Brown’s “Two Little Trains.” In short, the absurd imaginative play developed by Chris and his sons is perfectly matched by Tom’s exaggerated yet precise drawings.

While translating this book, I was constantly searching for the tone the author was trying to convey. I believe that “seriousness” is key to understanding its underlying tone. The protagonists, Shark and Train, are serious. They aren’t simply there to entertain the audience and then leave the stage. They’re genuinely competing with each other, intent on destroying each other. Therefore, the “harsh words” they utter from time to time are always vicious, conveying the feeling of wanting to kill each other. Some adults may consider such language bordering on vulgarity and try to get children to avoid it, but this is completely unnecessary. Children understand when to use them appropriately, and when truly impulsive, their harsh words may be even more extreme and heated, but everyone knows that they shouldn’t be taken seriously at that point. On the contrary, allowing children to frequently utter harsh words, while knowing that they are playing a humorous and playful game, can be a good way to relieve stress.

Furthermore, I’ve been putting quotation marks around the author’s use of the word “seriously” because I believe this demonstrates the author’s accurate grasp of children’s psychology. The dialogue between the shark and the train in the book actually comes from the mouths of two little boys. Apparently, in this kind of imaginative play, the more “seriously” you take it, the more fun it is. But even children tire of playing. After playing this game for who knows how long, even the children themselves grow tired. When the logic of the game becomes so absurd that even they themselves find it unbearable, it’s a sign of fatigue. Finally, the two boys, speaking their own voices (not the shark’s and the train’s), say, “This is getting ridiculous,” “I think it’s time for a break,” marking the end of the game. A delicious meal at this point is naturally the most satisfying way to enjoy it! This demonstrates the author’s precise grasp of children’s psychology and the rhythm of the story.

There’s another detail that I find particularly noteworthy. Early in the book, two boys rush to their toy box, searching fervently until they finally find the shark and the train. The other toys are scattered across the floor, and the two boys’ initial fight seems rather feral. But near the end of the story, when someone calls out, “Lunch time!” the boys’ expressions calm down considerably. And, surprisingly, the other toys, previously scattered across the floor, are now neatly arranged. It turns out they also form the backdrop and props for the story.

I think the author and the artist are trying to convey this understanding: children’s imaginative play is not only fun and intellectually stimulating, but also helps regulate emotions and unconsciously establish a necessary sense of order. Of course, at least that’s how I see it.

Ajia …

Written on2014Year9moon14Beijing