The Chinese New Year does create a lot of fragmented time, which can be interspersed with reading. I looked back and counted that from New Year’s Eve to the fourth day of the New Year, I also finished reading two Newbery Gold Medal works, one is the Chinese version of “Indian Suede Boots” and the other is the English version of Flora

and Ulysses.

I actually started reading Suede Boots a long time ago, but I always got stuck somewhere, never seeming to have the motivation to keep going. The Chinese New Year holiday was certainly quite boring (though quite joyful), so I finally found the motivation to finish it. Honestly, after finishing it, I still think it’s quite good—very touching and insightful. The only downside is that it doesn’t spur me on to read it on a regular basis. It’s packed with rich knowledge of American geography, like a half-road guide to the US, and offers plenty of tips for young writers. Of course, there are also some slightly suspenseful psychological coming-of-age stories. Overall, I think it’s the kind of book American teachers would love: skillfully written, rich in knowledge, and incredibly instructive.

Flora and

Ulysses is the new winner of the Newbery Medal in 2014. Out of strong curiosity, I got a Kindle version to read, which happened to coincide with the theme of this study session. The earliest book to win this American children’s literature award was “The Story of Humankind” by Van Loon, and the most recent one is this one. More than 90 years have passed. How have the two changed compared?

Honestly, reading this new book really tested my patience. After the first third, I was still completely bewildered. I had no idea what the author was trying to say, or what his “creative intention” was. It’s not that the text was difficult (it was actually quite easy to read), but I just couldn’t figure out where the characters, events, and dialogues the author had been creating were going. At times, it felt truly baffling. Fortunately, it was during the Lunar New Year holiday, so I had plenty of free time to spare. I could read it while idly enjoying morning tea, chatting, waiting in line, or sauntering on the water bus… I could find time to read it, and before I knew it, I was moving forward.

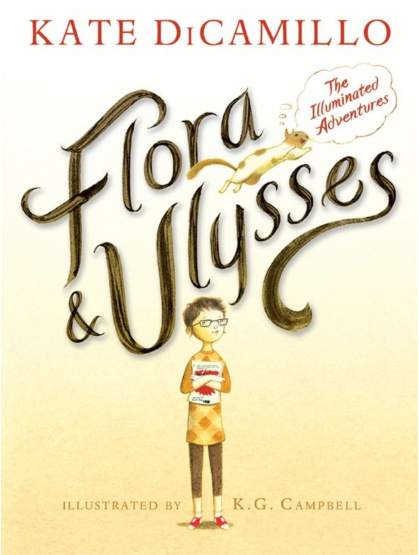

I have to praise the novel format of this book. The full name of the book should be: Flora and Ulysses: The Illuminated

Adventures (Flora and Ulysses: Picture Adventures), which means that at least part of the story in the book is told with pictures, so the creator is not only the author of the text, but also the illustrator is a co-creator. They are: Kate

Kate DiCamillo (author), KG Campbell

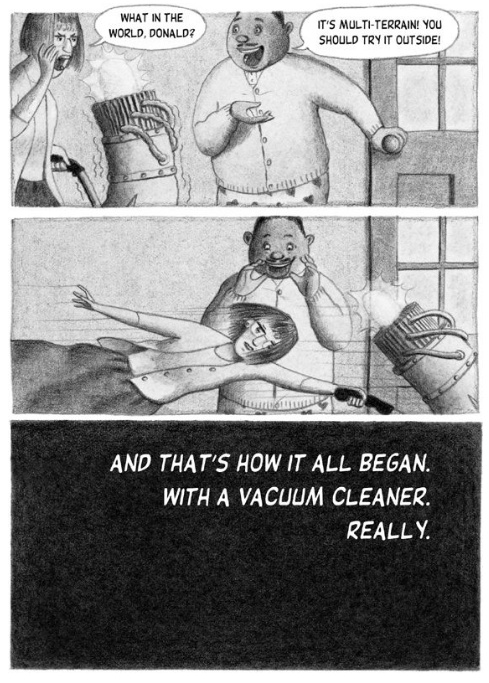

(KG Campbell, illustrator). Overall, this is still a novel, but the story begins with a comic, or rather, the introduction to the novel is a comic story. Take a look at this picture:

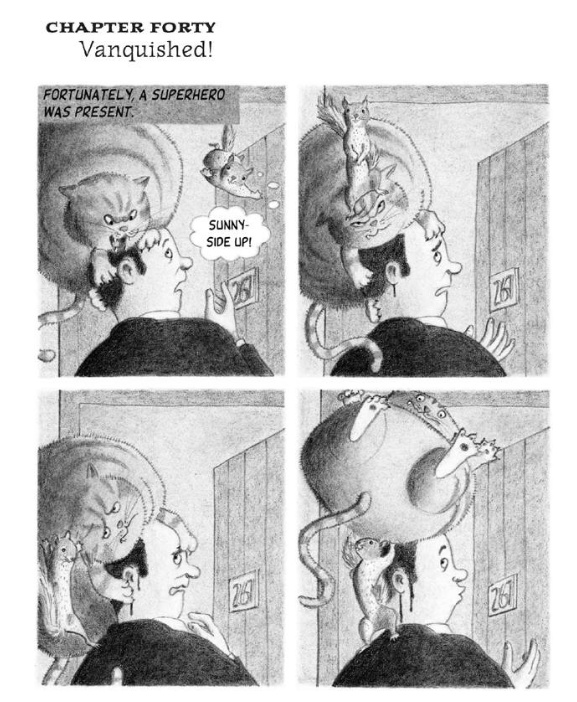

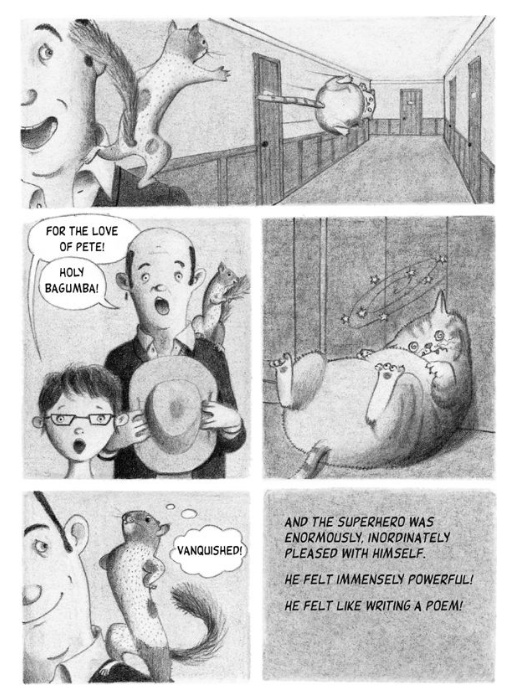

At first glance, you might mistakenly think that this is a comic book, and I think young readers will certainly enjoy flipping through it. In addition, as a fairly long novel, it naturally has chapters. I was shocked when I looked at the table of contents: there are 68 chapters plus an introduction and an epilogue! — How long will it take to finish reading this (the Water Margin annotated by Jin Shengtan also has 70 chapters). But when you really open the book and take a look, you will find that you have been “tricked”. Each chapter is pitifully short, only 5 or 6 pages long, and only 1 or 2 pages short. It is indeed very easy to read a chapter (it seems very fulfilling). Some chapters are even more exaggerated, but they are just 2–4 pages of comics, which seem to be a light and pleasant way to pass the “hard” reading. For example, Chapter 40 is as follows:

Overall, thanks to the combined efforts of the author and artist, reading this “novel” is truly enjoyable, though I still felt a bit baffled after reading the first third. I suspect this bafflement stems in part from cultural and age differences. Some of the popular American elements in the book felt a bit alien to me as a foreigner, and perhaps it’s just my age that makes me feel a bit unaccustomed to this comic-like narrative style.

I’m confident I know a bit about DiCamillo. Her novels, Winn-Dixie, won a Newbery Silver Medal, and Depero, The Romantic Mouse, won a Gold Medal a few years ago. The novels are pretty good, and the movies made from them are quite good. Another book, The Amazing Journey of Edward, is also quite good. Her writing is beautiful, her storytelling is highly skilled, and she’s often very tender and romantic. If I had to find a flaw, it’d be that her writing can sometimes seem a bit too preachy, or unnatural.

But a third of the way through “Flora and Ulysses,” I’m truly unsure what DiCamillo is trying to tell. The story unfolds like a soap opera. The main setting is the home of ten-year-old Flora, a comic book lover obsessed with a superhero (a rather ordinary one in real life) who she and her father once shared. But her father is now divorced from her mother, a writer who loves romance and hates comics. As the story opens, Flora’s mother writes on an old typewriter in the kitchen while she secretly reads comics upstairs, imagining the superhero. Then, she sees a new vacuum cleaner in the neighbor’s yard, frantically dragging the woman around, sucking up everything, until it finally sucks in a squirrel…

The story’s opening is certainly quite boisterous, and while it’s comic-book-esque, it still maintains a realistic approach. But then, somehow, the narrative suddenly shifts. Flora shouts from upstairs, her words seemingly floating in the air, transforming into a speech bubble. Then, she rushes downstairs to rescue the squirrel, and the squirrel’s consciousness becomes part of the story. Flora resuscitates the squirrel with mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, and then a miracle occurs: the hungry squirrel, seeking food, lifts the bulky vacuum cleaner with one hand! Flora instantly “realizes” that this squirrel is her superhero, and she names it after the brand of vacuum cleaner: Ulysses. Perhaps not coincidentally, Flora is the Roman goddess of flowers, and Ulysses is the Roman name of the Greek hero Odysseus.

At this point, the story enters a triple logic system (at least triple): (1) Real life: Flora and her writer mother, her father who is going to pick her up to play, the neighbor lady and her grandnephew William, and Dr. Meescham, the neighbor of her father’s apartment — their stories revolve around Flora and the squirrel Ulysses; (2) The comic book world: The logical system of the comic book world that Flora is immersed in. She sets the position of each real character based on her experience in the comic book story, as well as the countermeasures when encountering various situations; (3) Fantasy story or surreal life: The main line is the squirrel that has undergone magical changes. This Ulysses really has some superpowers. He can fly, communicate with people, write on a typewriter and computer keyboard, and even write poetry.

The story is advanced by the interweaving of these three logics. The first half seems quite random. As the squirrel Ulysses shows his superpowers again and again, the wheels of the story roll very noisily, but I don’t know where it wants to go… Until Flora’s mother decides to “get rid of” this annoying squirrel, the direction seems to become clearer (although privately I think it is still a bit forced).

The story naturally has a happy ending, but I can’t spoil the details. But looking back, you’ll find DiCamillo once again demonstrates her masterful storytelling skills, infusing a homely tale with fantasy and comic book elements, ultimately achieving the warmth and romance she’s so adept at. The illustrators’ collaborative efforts have made this story incredibly light and lively to read.

I’m particularly noteworthy for the fact that, despite incorporating numerous popular elements and giving the book a comic-like feel, the author manages to craft a sophisticated approach to language, seemingly inadvertently incorporating some challenging yet apt vocabulary. This is especially true through the involvement of William, a voluble 11-year-old boy obsessed with science and philosophy, and Mrs. Meescham, a somewhat mystical doctor of philosophy, who imbues the story with a wealth of scientific terminology and philosophical reflections. I found this to be quite engaging and a testament to the author’s skill. The delicate handling of language, even the exploration of poetry, and the use of squirrels to further the storyline, are also quite successful, and I think they will be very appealing to both primary and secondary school teachers. Overall, I think these seemingly “byproducts” are even more successful than the book’s main plot.

Based on my experience after just one read, I think this is a fairly successful work, but it may not be a classic, primarily because it seems to lack any truly emotionally touching moments. However, because it successfully integrates various elements, it will undoubtedly be enjoyed by many children and adults (especially teachers). Overall, it’s a very enjoyable book.

Ajia …

Beijing, February 2014