—— Reflections on the Translation of the Second Chinese Edition of “The World of Peter Rabbit”

Readers familiar with “The Tale of Peter Rabbit” and related stories will undoubtedly be captivated by the beautiful illustrations created by Miss Potter over a century ago. Today’s critics, hailing it as “the pioneering work of the modern picture book,” tend to focus on Miss Potter’s artistic achievements. As early as 1904, British reviewers praised the “loveliness and wit” of her illustrations and unhesitatingly declared her to have a “perfect brush.” Interestingly, if left to her own devices, Miss Potter would probably prefer to be considered primarily as a writer.

The Tailor of Gloucester, included in the second volume of the Chinese edition of “The World of Peter Rabbit,” is a long story with far more text than pictures. It is also Miss Porter’s most cherished of her own little books. Of course, she also loves the “masterpiece” “The Tale of Peter Rabbit,” but she has a deeper affection for this meticulously crafted tailoring book.

Although more than 100 years have passed, thanks to the unremitting efforts of biographers and researchers, and thanks to the preserved collections of letters, especially Miss Porter’s early secret diary of more than 200,000 words that was deciphered by later generations, we can basically outline the ins and outs of her early works.

The Tailor of Gloucester is based on a true story she heard from a distant cousin. In 1894, when she was 28, she was allowed to stay at her cousin’s house near Gloucestershire for a few days. This trip had a profound impact on her. During her subsequent visits there, she heard a story: a tailor named Pritchard in Gloucester was rushing to make a vest for the mayor. When he left on Saturday, he had half the work left. However, when he returned on Monday, he found that the vest was almost finished except for one buttonhole. A small note was pinned on it with a needle, saying “No thread”. The tailor was puzzled and surprised. He hung a small sign in the window of his tailor shop: “Our vests are made by night fairies!” — If it were someone else, they might think this was just a gimmick to attract business, but it fascinated Miss Potter because she was particularly obsessed with this kind of fairy fairy tale in life.

Pritchard’s tailor shop, now a memorial

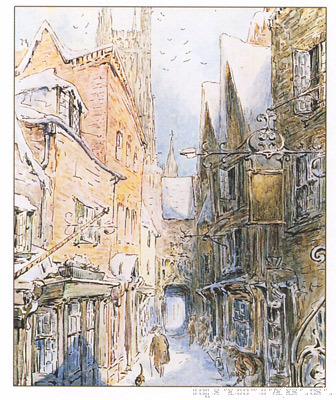

Snow scene in the story

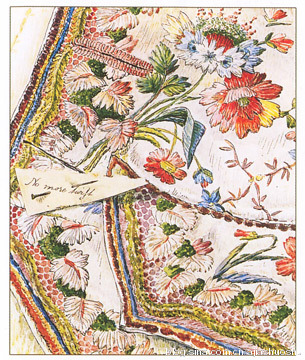

From the first day she heard about the story, she diligently worked to complete the unknown aspects of her imagination. She put in a lot of meticulous work, as recounted by many people: she visited Gloucester City specifically to sketch the exterior of the legendary tailor’s shop, the surrounding houses, and the streets. She painted the story’s College Road scene under strong summer sunlight, simulating an imagined winter snowscape. She later visited tailors in Chelsea and even found a tailor’s shop on London’s Old Street, ripping off a button and mending it there just to observe closely. She even spent hours at a London costume museum, observing and sketching the magnificent 18th-century garments. Clearly, she had already had a clear vision of her imagined tailor’s story, but it wasn’t until December 1901 that she completed the initial version. The story takes place in the 18th century, and the tailor’s work is assisted by a group of adorable mice! The initial version of the story was quite long, consisting of only 12 watercolors, interspersed with numerous nursery rhymes, including authentic Scottish ones, and she even added annotations in the Scottish language.

It would be hard for people today to understand that the story Miss Porter had painstakingly conceived and crafted over several years was actually just a Christmas present for a ten-year-old girl! Frieda was no one else; her brother was Noel, the recipient of the letter story “The Tale of Peter Rabbit.” Originally, Miss Porter had simply written the story to entertain herself and the children of her friends and family. However, inspired by the success of Peter Rabbit, she began to plan for a proper tailor’s book. Before Christmas 1902, she printed another 500 copies of “The Tailor of Gloucester” at her own expense. This self-printed edition proved popular, especially with older women. Vaughan Publishing Company, already working closely with Miss Porter on her second book, “The Tale of Squirrel and Plum,” also began to seriously consider the tailor’s book. However, there was a problem: the book would require major revisions!

Title page of a self-printed edition of a tailor’s book

Although the primary source of the revisions was Miss Porter’s future fiancé, Mr. Norman Vaughan, she maintained a rather complex attitude toward the book. On the one hand, she was deeply captivated by the story, largely due to its inclusion of many personally cherished elements, such as a dozen nursery rhymes she particularly favored. On the other hand, she felt the publisher’s suggestions were reasonable, and that she felt she had to make some painful sacrifices for the sake of a more accessible publication. Furthermore, she believed the story wasn’t for children, and should be read by ages around 12. To put it bluntly, it was originally a story she had created for her own amusement! Yet, she compromised, and after extensive deletions, partial rewriting, redrawing, and additional illustrations, she finally arrived at the version we see today. Correspondence reveals that the revision process took six months, with the manuscript finally being completed in late June of the following year.

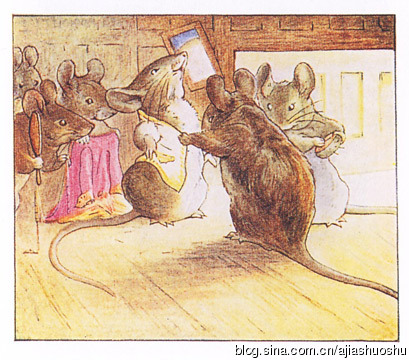

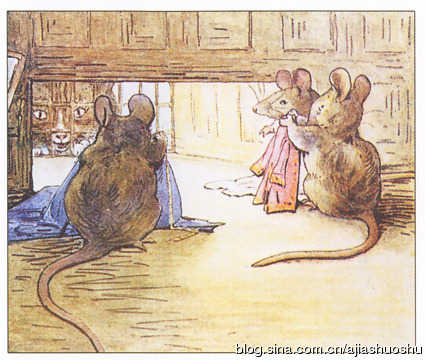

The final published version almost cut all the nursery rhymes. But Miss Porter couldn’t bear to let go, so she came up with a clever idea. She re-planned the structure, making the highlight of Simpkin’s Christmas Eve wandering and discovering the mice’s secret very compact, and retained six nursery rhymes that were embedded in the story and played a role in driving the plot, making them an inseparable part. For example, the little mice who helped make the vest first sang a cheerful nursery rhyme that teased the tailor, attracting Simpkin to the window of the tailor’s shop. The hungry kitten couldn’t get in without a key, so he could only stand anxiously outside the door. At this time, the mice laughed and sang:

“Three mice sat down to spin together,

A cat came over and stared inside.

My little baby, why are you so busy?

We make clothes for gentlemen.

Can you please let me in and help you with the thread?

Oh, no thanks, Miss Cat,

You’ll bite our heads off!”

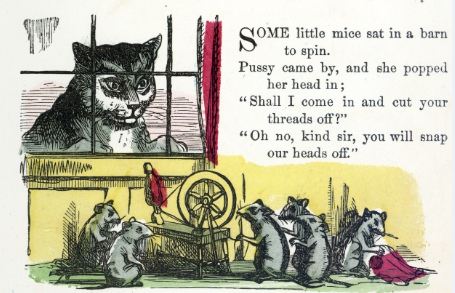

The top picture is an illustration by Miss Porter; the bottom picture is an illustration from a collection of nursery rhymes published in 1868

It is adapted from another song called “some little mice sat in a barn to

The nursery rhyme “spin” was probably read by Miss Porter as a child, and it was included in the illustrated collection of nursery rhymes published in 1868. Her adaptation not only improves the rhythm, but also seamlessly integrates with the tailor’s story. Even the most demanding editor would have to give in! You see, her obsession with word games is no less than her painting.

In 1916, when the commemorative edition of the Dressmaker’s Book was about to be published, Miss Porter confessed that it was her favorite of all the little books. However, to be honest, she preferred the version she printed at her own expense, perhaps because there was more magic created by pure words in that version.

Careful readers may also notice the following quote on the title page:

“I want to spend money to buy a dressing mirror,

Hire him twenty or thirty tailors…”

This line from Shakespeare’s historical play “Richard III” appears here. Why? Because it’s spoken by the Duke of Gloucester, who later became Richard III. The Duke of Gloucester, immortalized in Shakespeare’s literary creation, and the Gloucester tailor, by chance, found himself in Miss Porter’s writings. Another wonderful coincidence!

Years later, two assistants to the real-life tailor, Mr. Pritchard, revealed that the magical vest was actually a job they had secretly completed at the tailor’s shop on weekends, and that their subsequent silence was a joke on their employer. However, by then, people had largely ignored this revelation. When Mr. Pritchard died, his tombstone became a beloved landmark in Gloucester, inscribed with “The Tailor of Gloucester.”

Miss Potter’s Secret Diary (Ages 15–31)

Miss Porter’s involvement with Shakespeare was no accident. Her obsession with Shakespeare was long-standing, as evidenced by her secret diary entries, which reveal she often spent days and nights secluded in her cabin memorizing his plays. On October 10, 1894, she summarized: “I now know Richard III, four-fifths of Henry VI, three pages short of Richard II, King John in four acts, more than half of A Midsummer Night’s Dream and The Tempest, and half of The Merchant of Venice and Henry VIII. Thus, in about a year, I have learned six plays.” This list reads like a wealthy man’s calculation. So, what was the approximate level of mastery she was referring to? A table in her diary entry for November 6, 1895, explains that she had achieved her self-assessed best level of mastery in Richard III and Henry VI, meaning “not more than six lines omitted and not more than twelve errors in important words”! We have every reason to believe, therefore, that when Miss Porter wrote that quotation on the title page of The Tailor of Gloucester, it was done so spontaneously.

In a letter written by Miss Porter to Mr. Norman on June 8, 1905, they discussed the revision of “The Story of Mrs. Tithorne Winthorn”. They exchanged letters with similar contents quite frequently, and it seemed that they had completely replaced love letters with such letters. This letter mainly discussed whether the word “no” should be used or not. That was the place where Lucy heard Mrs. Winthorn singing through the door. Miss Porter wrote in the letter: “I think the grammar of this ballad is not right; the problem lies in the word ‘no’. If it is changed to

‘Smooth and hot – red rusty spot

never here be seen – oh!’

That should be right. She (Mrs. Winthorn) should be in a state of exorcism to remove stains and rust, just like Lady Macbeth! This is an imperative, so it is unreasonable to use ‘no’ with the vocative. Here it says ‘no

spot’ is very contradictory. …” Miss Porter was like a grammarian at this moment. She probably thought of the chilling murmur of Lady Macbeth in the sleepwalking scene in Act 5, Scene 1 of Macbeth: “Out,

damned spot! Out, I say!

As we get to know Miss Porter during her peak creative career, we discover she seemed to be under a captivating spell, constantly conceiving, observing, collecting material, writing, and drawing. Whether writing to herself, communicating with adults and children, or preparing for publication, she approached her work with unwavering care, meticulously weighing every word. She tirelessly revised, discussed, and re-revised her work, striving for perfection. Today, when we read her children’s writings—letters, stories, and published works—we are easily impressed by the playful blending of nature and everyday life, the fairytale world of fantasy and the real world. However, the reader might overlook the painstaking effort that went into these works, spurred by the ease of reading.

For a time, Miss Porter was truly neglected by her country’s literary world. She married in middle age, becoming the happily married Mrs. Hillis, and, as if under a new spell, yearned to become a true farmer (which she ultimately succeeded in doing). By then, her eyesight was failing, and she could no longer paint those dreamy, lovely pictures. British critics rarely mentioned her, and the public image of Peter Rabbit’s creator seemed long dead. Interestingly, however, across the pond, American literary circles held her in high esteem. American readers, publishers, and literary critics made pilgrimages to visit this nearly reclusive farmer, and she gladly contributed to their work.

Miss Porter continued to write until the end of her life. In 1942, a year before her death, she published several short articles in the famous American literary review magazine “Horn Books”, one of which was “The Lonely Mountains”.

Lonely

Hills is a beautiful prose piece, describing the mountains and moors of the Lake District she deeply loved. Even during the stalemate of World War II, she still found the pleasure of viewing the distant German air raids as a unique spectacle. However, due to severe shortages of supplies and labor, her farm struggled to survive. During her final year, she was often bedridden due to illness.

One day, she suddenly remembered an old woman named Katie MacDonald, a washerwoman she had known as a child in Scotland and the prototype for Mrs. Tithorne Winthorn (whose animal form was inspired by her hedgehog of the same name). Miss Porter, lying sick, smiled. She casually grabbed a rolled-up newspaper wrapper and wrote a leisurely message on the back, recalling the short, robust, cheerful old woman who seemed to radiate magical powers while washing clothes. But when she saw the two young girls helping to step on the clothes, she couldn’t help but recall her own girlhood: “What a wonderful time it was, but it’s too bad it’s gone.”

Miss Potter wrote fairy tales for children, but they also contained her entire life.

The Argentine Primera División in Beijing in November 2012

Related blog posts:

Picking up pearls from the sea of words: Essays after the translation of “The World of Peter Rabbit”

Masters of the Art of Storytelling for Children (I)

Masters of the Art of Storytelling for Children (Part 3)