After receiving the notification letter for the children’s book reading group yesterday (theme: Love, marriage and family in children’s books), this sentence kept popping up in my mind: what we talk about

when we talk about love, so much so that I had to write something to sort out my messy thoughts.

what we

talk about when we talk about love

It is the title of a short story by American writer Carver and the name of the collection of short stories that includes it. There is already a Chinese version, “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love” translated by Xiao Er of Yilin Press.

, a superb translation, very enjoyable. But I wouldn’t recommend reading it unless you’re mentally strong. Carver’s beautiful writing is imbued with a kind of despair I’d call it—though there’s also a certain warmth, yet still despair—that can deeply move even the mentally strong, unless that strength is merely numbness.

I was probably drawn to this book because I think it’s the polar opposite of children’s books. It’s incredibly realistic, so despairingly real, it has a bit of Kurt Cobain in it, the great singer forced to find his own way out. Carver was slightly better off; his alcoholism didn’t kill him, and once things got better, he managed to quit drinking. But, ironically, he succumbed to the lung disease brought on by his smoking addiction. A closer look at their success reveals that it was largely “benefited” by difficult family situations and childhoods; contemplating their early deaths also seems to be deeply connected to those difficult situations.

Love, marriage, family, childhood, growth… Love, marriage, family, childhood, growth… Love, marriage, family, childhood, growth… is also a kind of reincarnation.

»> Continuing the Gossip Chapter of Love Cultivation — A Story of a Mother Who Abandoned Her Child…

Even if the marriage chain is severed and the next generation is abandoned, it is said that the angry energy may not necessarily be cut off, but can be dissipated to others and passed on through others.

I seem to have strayed from the topic.

![[Children's Book Study] What do we talk about when we talk about love... [童书研读]当我们谈论爱情的时候会谈论什么……](https://ajia.site/blog/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/5881300ct9225920a67dd.jpg)

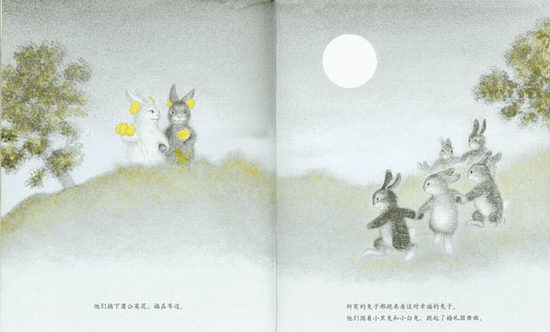

The one I want to talk about most in children’s books about love and marriage is “The Black Rabbit and the White Rabbit”. It reminds me of Edward Lear’s absurd poem “The Owl and the Cat-Girl”.

Owl and the Pussycat). The former is ultimate enough, the latter is funny enough.

The family in children’s books that I want to say most is Now One Foot, Now the

Other (translated as “First the Left Foot, Then the Right Foot” in traditional Chinese) revolves around the love between a grandfather and a grandson. It is tear-jerking, very realistic, and yet rich in symbolic meaning.

There are roughly two types of love in children’s books. One is pure, fairy-tale-like (or, for that matter, anti-traditional fairy-tale-like), where “they lived happily ever after” is the perpetual theme, even in the ending where “the cat never resurrects.” The other is a continuation of family ties, because the love felt in childhood is inseparable from family ties.

At the other extreme, discussions of love in adult literature are rarely pure; purity can even seem equated with affectation. From the casual love stories in Maurois’s “Dinner Under the Chestnut Trees” to those discussed in Carver’s “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love,” I don’t see much difference in substance, beyond the distinction between outward elegance and vulgarity. The final story of the elderly couple is simply too powerful, yet too pure, for Carver to present it openly. He must first, like a “normal” adult, stir it until it’s sufficiently muddy (enough to pique the murky interest of “normal” adults) before suddenly tossing it out. In fact, if Carver were writing a children’s story, he could have easily cut out the rest.

So what’s the biggest difference between adult literature and children’s stories when it comes to discussing love? I think it probably lies in the word “desire.” Just think about it: if it were a pure, fairy-tale love story, one that was completely free of lust, how many adults would be willing to read it? And what’s the difference between lust and love?

I recently read Tao Yuanming’s “Idle Feelings,” and I realized that even this serene and indifferent master had moments of “emotional expression.” Whether he ever “stopped at propriety and righteousness” is unclear. Even if some insightful scholars have called it “a flaw in a flawless jade” and a bit “debauched,” why does this short fu poem remain so captivating and captivatingly beautiful? I think the reason is simple: the writer and reader are both living adults. There’s no going back, so let’s just make the best of it. O(∩_∩)O~

In this sense, love in children’s books is fundamentally metaphysical.

However, this metaphysical lesson is also compulsory and can only be learned in childhood.

Just imagine, will there still be a chance to repair it when you become an adult? There is really no going back!

Those who are interested in children can also come and practice, and practice in the children’s book, which is a big discount^_^

Written on Red Mud on October 8, 2010

[Children’s Book Study] What do we talk about when we talk about love…