Continued from the previous chapter:Masters of the Art of Storytelling for Children (V)

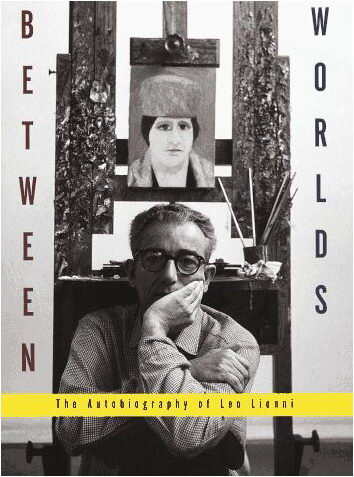

Leo Lionni

Today, a train ride from New York’s Grand Central Station to Greenwich, Connecticut, takes about an hour and a half, but in 1959 it would have taken at least three hours. Imagine being on that train with two energetic children, ages three to five. What stories would unfold along the way? Would you have imagined you’d have written a world-famous picture book by the time the train arrived? Even Leo Lionni (1910–1999), returning home with his grandchildren, had no such idea. At the time, his career was still far from being a children’s book.

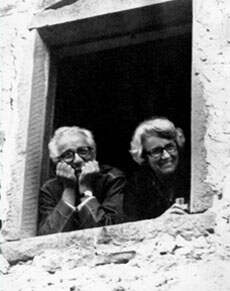

Family photo (from left): youngest son Paolo, Leonie, wife Nora, and eldest son Mannie

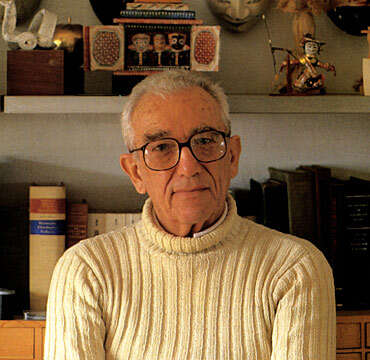

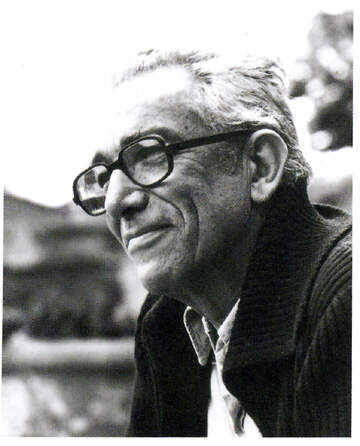

Lionel Leoni was 49 years old that year. He had married and had children early, and his son continued the tradition, so he was already a grandfather of two. He looked quite young, with a slightly thin face, large earlobes, and bright eyes. He was easygoing and always spoke with a kind smile. But he was also a remarkably quiet man, often lost in thought, giving off a certain noble melancholy.

Lioni was an artist, but his primary focus at the time was advertising and commercial design. He designed several cars for Ford and later held senior design positions in the printing and magazine industries, most notably serving as design director for Fortune magazine for ten years. During this period, he held numerous solo exhibitions of his paintings and designs in Europe, Japan, and the United States. He served as president of the American Society of Graphic Arts and chaired the 1953 International Design Conference. He also held countless other titles. However, in 1959, at the peak of his career, Lioni decided to step away from it all. He announced that at the age of fifty, he would return to his adopted homeland of Italy to start a new life. Perhaps no one, except his wife, truly understood or supported his decision. In fact, in his second picture book, “The Inchworm,” Lioni hinted at a hidden secret: he was tired of “success” that didn’t truly belong to him. He wanted to find his own voice, his own way.

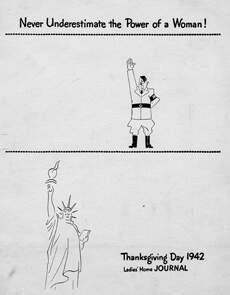

A famous advertisement designed by Lionel Messi for a women’s magazine during World War II

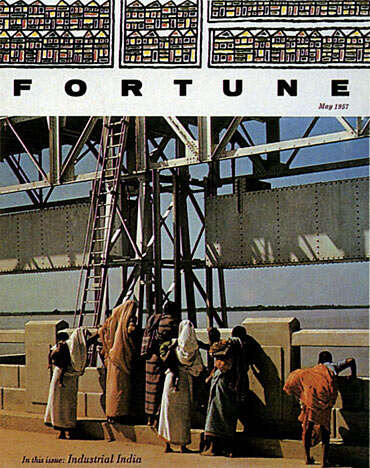

Fortune magazine cover, May 1957 (when Lionel Messi was design director)

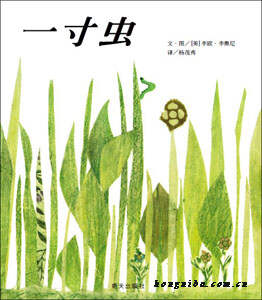

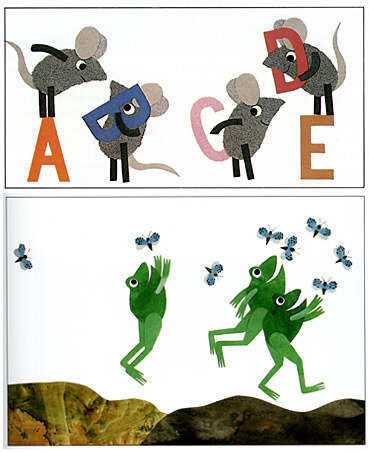

The Inchworm — Lionel Leo’s second picture book

One of the pages of “One Inch Worm”

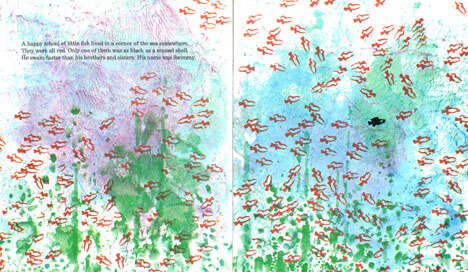

It was as if fate had orchestrated this marvelous journey just for Lioni. The train started, and Grandpa, seemingly calm but with a hint of fatigue on his face, sat down. The two little rascals, after a brief silence, were ready to stir up trouble. Grandpa, an artist after all, struck upon an idea, ready to preempt them. “Let me tell you a story,” he declared, a universal remedy for children everywhere. He spread out his briefcase as a backdrop, tore out some colored pages from a Life magazine, and then tore out round pieces of paper of different colors. As he placed the pieces of paper on top, he began to tell the story: “This is Little Blue. Little Blue lives with Papa Smurf and Mama Smurf. Little Blue has many friends, but his best friend is Little Yellow…” And a miracle happened: not only were the two little rascals captivated by the story, but even the adults nearby were drawn in. The journey was truly delightful.

Merged image of some pages from the French version of “Little Blue and Little Yellow”

Back home in Greenwich, the three of them were still brimming with excitement. Lioni told the children that if they wanted to preserve the story, they had to turn it into a book. So, this master of graphic design used the raw materials to create a small book. As luck would have it, an editor friend visited their home the next day and saw the book. He was so impressed that he urged Lioni to publish it. Unexpectedly, the book became a huge success. This is the book we read today, “Little Blue and Little Yellow.”

Cover of the Chinese version of “Little Blue and Little Yellow”

Later, Leoni really switched to picture book creation. He and his wife returned to Italy, living in a 17th-century farmhouse in the Tuscan hills, where he devoted himself to creating picture books. However, he would return to New York half of the year to handle some of his work.

The Lionni couple returned to Italy to settle down

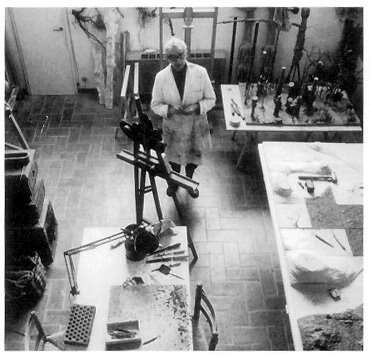

Lionel Messi in his studio

In the latter half of his life, Lioni created over forty picture books, the most famous of which include “Alfred the Field Mouse,” “The Little Black Fish,” and “Alexander and the Clockwork Mouse.” Lioni pursued a solitary approach to picture book creation, rarely influenced by others in the children’s book industry, and even editors rarely interfered with his work. His paintings bear traces of De Stijl and abstract art, and his stories are richly allegorical. While some have hailed him as the “Aesop of the 20th Century,” adults often worry that “children won’t understand” his books, and some even use his picture books as supplementary reading for yoga practitioners. However, these controversies haven’t prevented generations of children from being captivated by Lioni’s works, particularly the iconic characters in his stories: Alfred the Field Mouse, the Little Black Fish, Cornelius the Crocodile, Alexander the Mouse…

For more tidbits about Lionel Messi, please refer to my article:[Postscript] Chatting about Leo Lionni’s life

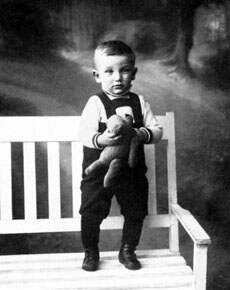

Leo Lionni holding a teddy bear

Leo Lionni as a child (sketch drawn by his uncle)

The newlyweds Leo and his wife (Leo got married at 21 and became a father at 23)

It is said that Leo was initially fascinated by Nora’s elder sister, but eventually found out that he fell in love with her younger sister.

Italian is the fifth language Leo has learned, but he considers Italy his hometown.

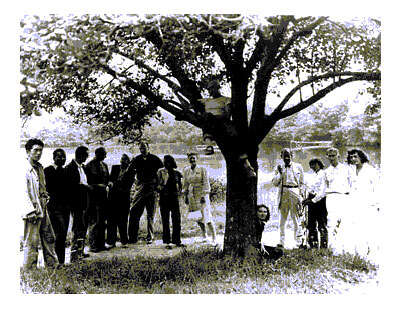

This is a very rare group photo (taken in the summer of 1946)

The third from the left is Leo Lionni, and the fifth is his wife Nora

This is a group of teachers from the famous Montenegro University at that time.

From left: L. to R. Leo Amino, Jacob Lawrence (painter),

Leo Lionni (graphic artist), Ted Dreier, Nora Lionni,

Beaumont Newhall, Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence (painter),

Ise Gropius, Jean Varda (in tree), Nancy Newhall,

Walter Gropius (architect), Molly Gregory,

Josef Albers, Anni Albers

The two on the far right are the famous Albers couple

Lionni died at his home in Italy on October 11, 1999. He suffered from Parkinson’s disease in his later years, but this did not destroy the artist’s will, and he continued to live a very determined and peaceful life.

According to her granddaughter, Anne Lionni (one of the protagonists of the aforementioned train story), her grandfather was a passionate and talented musician. He never even saw sheet music, yet he could play many of his favorite pieces effortlessly. As a child, she often heard him play the accordion. Later, she watched him learn to play the Spanish flamenco guitar, and later, the Indian sitar. Even when Parkinson’s disease prevented him from playing these instruments, he would still play some of his favorite pieces on her granddaughter’s piano.

After Leo passed away, his wife Nora moved in with her granddaughter and her family. Anne was interviewed about her grandfather’s life and works.If you want to learn more, you can visit this website Remembering Leo »»

Well, that’s all I have to say about Leo Lionni for now. Actually, everything about him is in his own books. His works need to be read together in several volumes to get a clearer understanding of the whole.

To know what happens next, please wait for the next episode.

Masters of the Art of Storytelling for Children (Part 7)