Continued from the previous chapter: Masters of the Art of Storytelling for Children (Part 3)

Speaking of the United States——

Early European intellectuals viewed the United States as a land of rampant piracy. In the 1840s, when the British literary giant Charles Dickens first visited the United States, he was shocked by the rampant and blatant pirating of his own works. Inspired by this, he wrote a pamphlet specifically mocking and criticizing this phenomenon. During his travels, pirated copies of this pamphlet were readily available.

Cover of a 1904 American pirated edition of Peter Rabbit

In 1904, pirated copies of The Tale of Peter Rabbit also appeared in the American market, causing considerable headaches for Miss Porter and the Vaughan Company. In that era, in that publishing environment, the United States could not have its own picture book masters.

The earliest masterpiece of a picture book in the United States is undoubtedly Wanda Gag’s (1893–1946) A Million Cats (1928), which won the Newbery Medal Silver Medal from the American Library Association in 1929. Today, the Newbery Medal primarily recognizes children’s literature, but the Caldecott Medal, specifically for picture books and illustrators, was not established until 1939. The establishment of such an award by the National Library Association is crucial, not only providing spiritual encouragement to the work and its creators but also providing substantial support for the work’s circulation and the creator’s livelihood. Winning the award also means that the book will be included in the collections of all libraries in the country, significantly boosting the book’s market share.

Cover of the Chinese version of “A Million Cats”

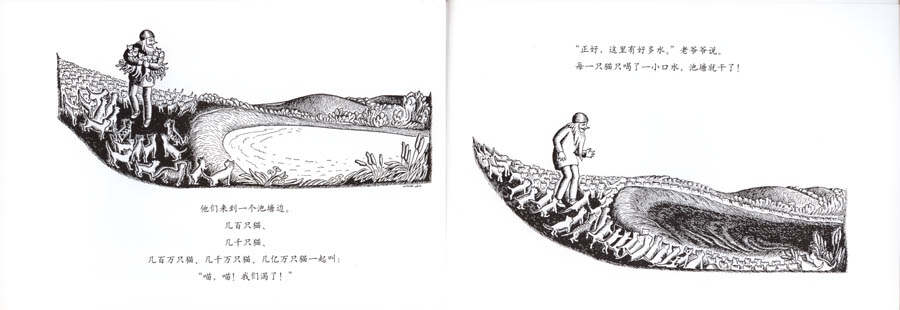

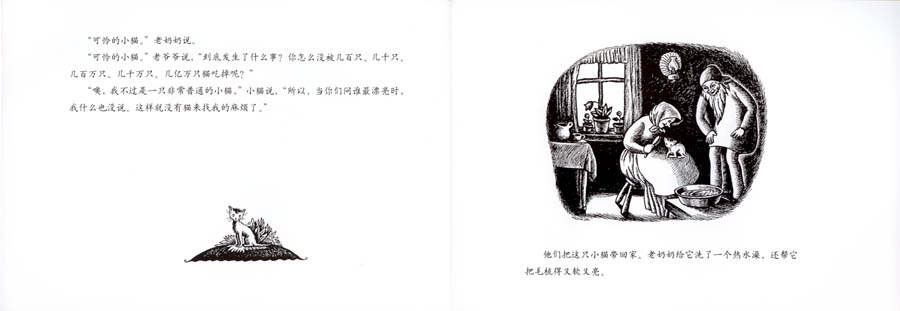

Page 1 of “A Million Cats”

Inside page 2 of “A Million Cats”

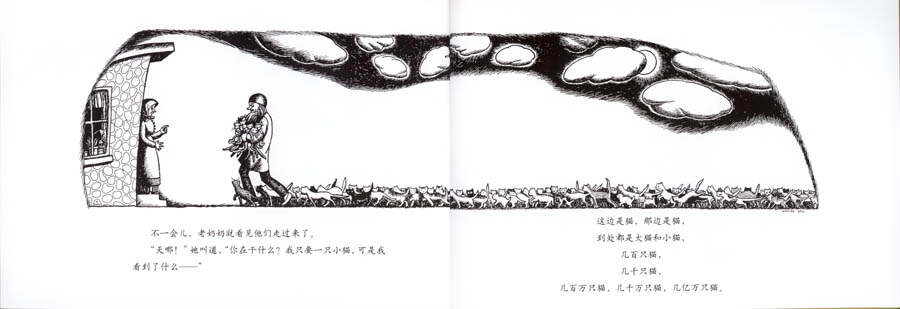

Page 3 of “A Million Cats”

The Great Depression in the United States ushered in the golden age of children’s books after the 1930s. Perhaps after people’s material desires became extremely inflated and their minds became overheated, they were particularly eager to nourish their souls and also hoped to reflect quietly on the education of the next generation.

Some famous American picture books from this period have also been introduced and published in mainland China in recent years, such as Madeline (1939) by Ludwig Bemelmans (1898–1962).

Robert McCloskey (1914–2003) Make Way for Ducklings (1941), Serge Picks Blueberries (1948), and Morning on the Seashore (1952)

Marie Hall Ets (1895–1984) In the Woods (1944) and Come Play with Me (1955)

Virginia Lee Burton (1909–1968)‘s “Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel” (1939), “The Little House” (1942), and “Caddy and a Big Snow” (1943), among others.

Every outstanding work is born from a wonderful opportunity, and the stories here are full of different flavors.

In the Forest Illustration 1

Mary Ho Ace and her “In the Woods”

“In the Forest” was indeed written near a forest, and behind it lies a somewhat poignant story. The book tells the story of a boy who, blowing a horn, takes a walk through the forest. He awakens a lion, summons a baby elephant and a giant bear, as well as kangaroos, cranes, monkeys, rabbits, and other animals. They parade, picnic, and play games… until the boy’s father arrives to pick him up, and the forest returns to a profound tranquility. The story sounds lively at first, but the images are those striking black-and-white prints. The narrative is told in a gentle rhythm, simple yet repetitive, lingering, and lingering manner, creating a uniquely tranquil and slightly mysterious atmosphere.

Inside page of the English edition of “In the Forest”

Mary Ho Ace was nearly fifty when she wrote this story. She was at home in the woods outside Chicago, accompanying her beloved husband, who was terminally ill and nearing death. As she quietly awaited death, she felt surprisingly no fear, instead conjuring up images of forest animals and children. These memories were also from her childhood, as she was born in a small town in Wisconsin, nestled between a lake and a forest. As a child, she loved to escape into the dark woods and sit for hours, listening to the wind through the trees and waiting for the animals to appear. It was in this state of mind that she picked up her brush and began painting “In the Woods.” After her husband’s death, she left the forest and never returned. However, the story has two sequels: “The Forest Conference” and “That’s Me.”

“In the Forest” holds an indescribable magic that lingers in people’s minds. Japanese publisher Nao Matsui confidently declared it his favorite picture book of all time. Children have their own reasons for liking it, for example, enjoying imitating the story in the book by acting it out, as it’s a play inspired by a boy’s imagination. Later, a musician adapted it into a children’s musical, using a similar technique to “Peter and the Wolf,” imitating the animals to different tunes. It’s truly entertaining.

However, Mary herself firmly believes that her greatest contribution to American children’s literature is “A Story of a Baby,” published in 1939. This picture book, which remarkably accurately depicts the process from fertilized egg to newborn, is considered one of the earliest children’s sex education books. Her husband, Professor Harold Ace, a medical expert, provided her with considerable assistance in writing the book. But that’s another story.

Illustration 1 from The Story of a Baby (1939)

Illustration 2 from The Story of a Baby (1939)

Illustration 3 from The Story of a Baby (1939)

Illustration 4 from The Story of a Baby (1939)

Every time I read the last line of “In the Forest” where the little boy says “Goodbye, you have to wait for me to come back next time”, I can’t help but wonder if this is a metaphor for a solemn promise in the next life?

This person is gone now, and the living should be like this.

Photos of Mary Ho Ace and her husband, Professor Ace

To know what happens next, please wait for the next episode.

Artists Telling Stories for Children (V)