The origins of picture books

Picture book comes from the English word “picture book” and is called “ebon” in Japanese.

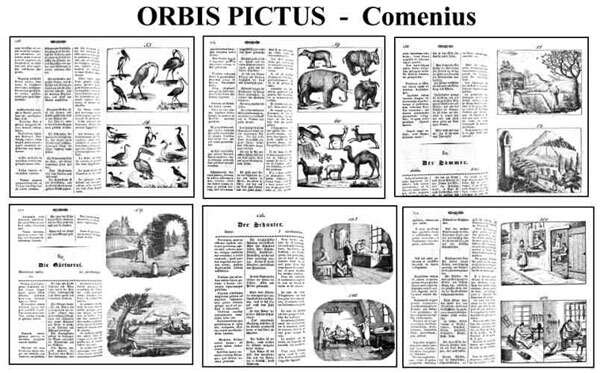

Comenius

Orbis Pictus, published in Nuremberg in 1658 by the Czech educator John Amos Comenius (1592–1670), is generally considered the world’s first picture book specifically for children. Today, this book is little more than an illustrated children’s encyclopedia, at most a prototype of a picture book, but at the time, it was of great significance. Comenius conceived of this children’s textbook years before compiling it. He believed that children needed special reading materials, and that combining pictures and text could achieve remarkable results, both entertaining children and making teaching more effective.

World Atlas

Inside page of World Atlas

As a 17th-century scholar, Comenius understood that children find pleasure in pictures. He also developed illustrated textbooks and dedicated himself to reforming children’s education, focusing on respecting children’s personality and liberating them. This was quite avant-garde at the time. The World Map had a lasting influence. Originally published in Latin and German, it was translated into numerous languages and was still being reprinted until at least 1780. Comenius is also revered as the founder of pedagogy.

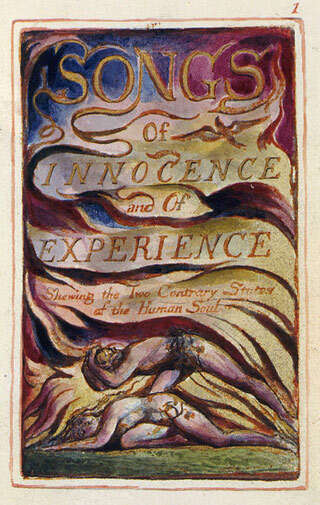

In 1789, the English poet and printmaker William Blake (1757–1827) created a beautifully colored illustrated collection of poetry for children, Songs of Innocence. However, the colors in the book were hand-painted, not machine-printed! In the first half of the 19th century, color printing technology gradually developed, and publishers and illustrators began to explore how to use color to lure children into the world of books.

Blake’s “Songs of Innocence and Experience” cover

In the opening chapter of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, published in 1865, there’s a classic line: Alice laments the book her sister is reading: “What good is a book without pictures and conversation?” This line could almost be considered a manifesto for modern children’s books. It at least suggests that by the second half of 19th-century Britain, the idea that children’s books should include illustrations had become a kind of social consensus.

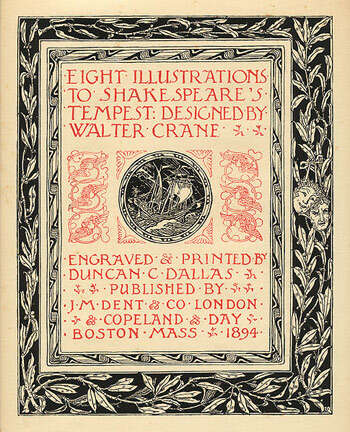

At the time, there was a publisher named Edmund Evans (1826–1905), also a painter and engraver. He was adamant about providing children with beautifully illustrated books, even in inexpensive editions. He collaborated with a number of outstanding illustrators to produce a large number of exquisite children’s books. Among the most famous were Walter Crane (1845–1915), Kate Greenaway (1846–1901), and Randolph Caldecott (1846–1886), all of whom are considered the founders of the modern picture book. The Greenaway and Caldecott Medals, two of the most prestigious picture book awards in the UK and US today, are named after the latter two.

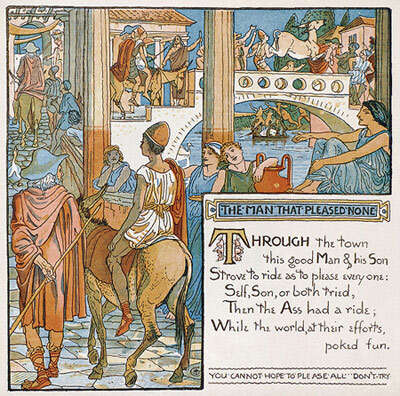

Walter Crane illustrations

Illustrations by Walter Crane

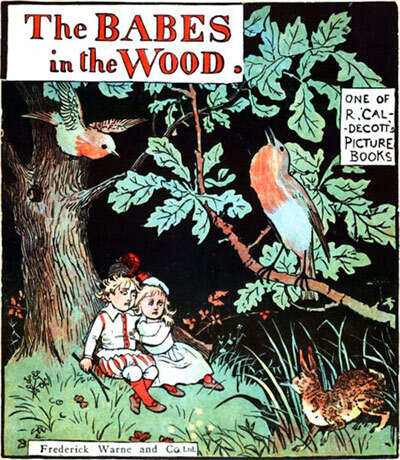

Randolph Caldecott

Caldecott’s works cover

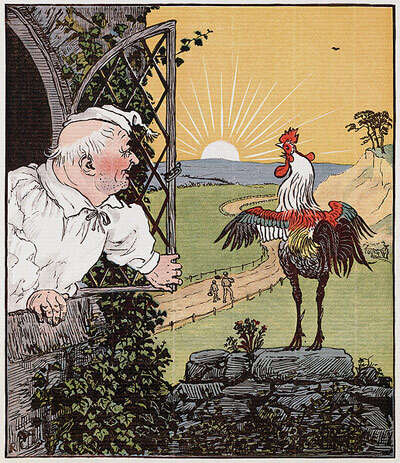

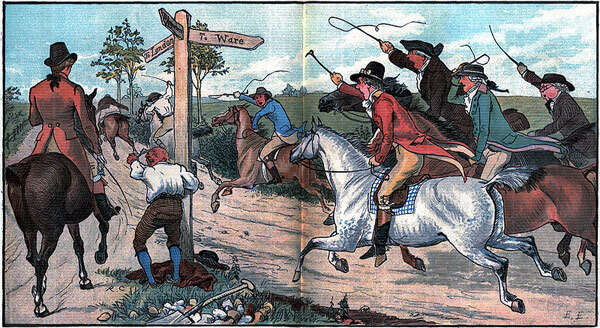

One of Caldecott’s illustrations

Caldecott illustrations

Kate Greenaway

Kate Greenaway Collection

The last painting of Kate’s long poem “The Pied Piper of Hamelin”

However, before Peter Rabbit came along, picture books in the truest sense of the word hadn’t been invented. Even those meticulously illustrated by master artists simply combined pictures with text. Illustrations made reading more enjoyable and easier for children to understand, but they didn’t play a decisive, essential role in the meaning of the work.

Japanese publisher Nao Matsui once defined picture books in his mind as follows: “Picture books have a unique relationship between text and painting. They use a leapfrog and rich expression method to express content that is difficult to express with just text or pictures.” If we use a formula to express it:

Text + Picture = Book with illustrations

Text × Painting = Picture Book

Only from this perspective can we understand why “The Tale of Peter Rabbit” is considered the first picture book in the modern sense.

To know what happens next, please wait for the next episode.

The masters of the art of telling stories for children (Three)