Illustrations for “My Ideal” by Xiong Liang and Wang Puzhi

Today is October 23, 2009 (Frost Descent), and the weather is beautiful. This day, like so many others, is so ordinary for some people that it seems as if it never existed. But for others, it may be a momentous occasion, worth anticipating and cherishing. Future historians may not even find room to include this date in their history books, because it’s possible that nothing truly happened on this day. But perhaps some will still remember it. For example, I will likely remember this day as a very happy “unbirthday,” even though it seems as if nothing happened, and nothing will happen.

I played a clip of Miriam to myself

Stockley sang Perfect

Day. I’ve been listening to this song a lot lately because I’m currently retranslating Potter’s Peter Rabbit. It always reminds me of that incredibly beautiful woman, sitting on a grassy slope in the English Lake District, meticulously painting the world around her with watercolors: the sky, the lake, the grass, the hares, the squirrels, the hedgehogs, the ducks, the dogs, the cats, the country mice, and the children. A dark cloud drifted in, followed by a slanting wind and a drizzle. She hurriedly gathered her paper, stood up, and, holding her sketchpad on her head, hurried toward the stone house on the hillside…another

perfect day……

But today I thought of listening to this song because I wanted to seriously praise a set of books: the recently published “Wild Child” by Xiong Liang.

http://landaishu.zhongwenlink.com/home/upload20083/2009102313354971.jpg

http://landaishu.zhongwenlink.com/home/upload20083/2009102313411660.jpg

http://landaishu.zhongwenlink.com/home/upload20083/2009102313424277.jpg

http://landaishu.zhongwenlink.com/home/upload20083/2009102313748121.jpg

http://landaishu.zhongwenlink.com/home/upload20083/200910231382986.jpg

http://landaishu.zhongwenlink.com/home/upload20083/2009102313814763.jpg

For over a year now, whenever I’ve talked with friends about Xiong Liang’s upcoming “Wild Child” series, I’ve been filled with sincere admiration: This picture book far surpasses Xiong Liang’s previous works! It marks a new height in Xiong Liang’s picture book creation. Whether it will become a landmark in the development of original picture books is hard to say, but I believe it will be a significant achievement that cannot be ignored.

The reason for such admiration is mainly due to the shock I felt when I saw the drafts of books such as “A Garden of Vegetables Became Spirits”, “My Ideal”, “Crickets and Grasshoppers”, and “We Want to Be No. 1” almost a year ago.

I remember visiting Xiong Lei and Xiong Liang at their studios. We had a wonderful chat, and Xiong Liang casually mentioned that he’d also illustrated a book based on a Beijing children’s rhyme, “A Garden of Green Vegetables Becomes a Spirit.” He’d originally planned to publish it, but seeing that Mr. Zhou Xiang’s picture book of the same name had already been published, which was excellent and well-received, he felt hesitant to bring it out. The inspector and I were incredibly curious and insisted on seeing Xiong’s version of the vegetables. When Xiong Liang unfolded it, we were overjoyed. In other words, it was fun! It really was fun. Compared with the graceful, delicate and gentle style of Zhou’s version of Green Vegetables, the style of Xiong’s version of Green Vegetables is rather rough, and at first glance even looks a bit like the particularly childish graffiti of a naughty boy; the story structure of Zhou’s version of Green Vegetables follows the style of a Jiangnan vegetable garden, as if it is a fairy tale taking place in a vegetable farmer’s vegetable garden, while the Xiong version pays more attention to its original fun in the interpretation of this nursery rhyme, alluding to the story of the White Lotus Sect in the Qing Dynasty, and there is a sense of wildness in the scenes of fighting and playing; what surprised us the most was that many of the images in the Xiong version of Green Vegetables were actually directly painted from photos of vegetables, fruits and melons, and they are very lifelike, which is a unique experience.

http://landaishu.zhongwenlink.com/home/upload20083/200910232218371.jpg

Illustrations for the bear version of “A Garden of Vegetables Becomes a Spirit”

We were all thrilled after reading it and urged Xiong Liang to publish it as soon as possible. Concerns about a potential conflict were completely unnecessary. These two books clearly differ in style and interest. Although both are adapted from the same nursery rhyme, the stories are vastly different. The more classic something is, the more it deserves different versions, just like “The Three Little Pigs” and “Little Red Riding Hood.” Vegetables with different flavors deserve to be enjoyed by both adults and children.

The Xiong brothers, somewhat excited by our Lin brothers, began to discuss their “Wild Child” concept. We then looked at “My Ideal,” crafted from small stones, the vividly written “Crickets and Grasshoppers,” and the particularly playful and creative “We Want to Be Number One.” What surprised us most was that the characters in these books were all children’s toys—pebbles, crickets, grasshoppers, ants, and, combined with the vegetables and fruits from the previous book, “it was a real mess!”—but under Xiong Liang’s brush, seemingly casual and simple strokes, we created incredibly vivid images. Even without the stories, revisiting these images and characters over and over again was deeply captivating and never tires of them.

http://landaishu.zhongwenlink.com/home/upload20083/2009102321623881.jpg

Illustrations for Cricket and Grasshopper

However, if this is all there is, the painter is still just a painter, not a creator of picture books.

I have always insisted that picture books are first and foremost for children to read, to be read to, and to tell stories to. It is not enough to have only beautiful and interesting pictures. They must also be able to tell stories. When telling stories to children, children should be able to respond, and it is best if they can respond wholeheartedly.

Of course, I also accept the view that different genres of picture books should coexist, and that’s true. Sometimes, we need picture books to satisfy the nostalgia of those of us who have long since left childhood. We also need to convey to children what we feel is necessary, even if they don’t immediately understand or even don’t comprehend it, but we hope that “they’ll understand when they grow up.” As a result, some picture books are highly appreciated by adults (especially those in refined literary circles), and children, out of curiosity and basic courtesy towards the storytellers, listen attentively to these stories. Even if their reactions are muted, we still firmly believe that it benefits children and is worthwhile. This is actually my own view, albeit a somewhat helpless one at times. Even a good cook cannot cook without rice!

I feel like most of Xiong Liang’s previous picture books fall into a similar category: excellent works that appeal more to adults than children, with sophisticated language, but not ideal for direct storytelling with children. The inspector and I prefer the two “Peking Opera Cats” books because they’re more suitable for storytelling and acting, and they also allow us to connect with our favorite Three Kingdoms stories. I also particularly like “Su Wu Shepherding Sheep” because it makes a great songbook and also connects with a favorite historical story.

Original picture books should be more about telling stories directly to children and evoking their whole-hearted response. This is one of my more stubborn ideas.

A few days ago, when I finally got my hands on the first batch of six “Wild Child” books, I felt a long-awaited urge: I immediately took the books home and told them to my daughter! The result was even more remarkable than I’d anticipated. Perhaps because she was bored with homework, her eyes lit up and she was so excited to hear the “Wild Child” stories. After reading “Any Cat Is Useful” and “The Invisible Horse” (I usually start with the ones I find more challenging), she burst into laughter and insisted on “reading it again.” Her mother urged her to “go to bed” and grumbled, “You’re already in fourth grade, and you’re still so stubborn!” But she persisted. I had to smooth things over and tell her to go through “A Garden of Vegetables Becomes a Spirit” together first, and we’d talk about the rest tomorrow. My daughter reluctantly agreed—it seems these books have a side effect, and they might actually be making her wild!

But, to be honest, telling stories with these six books is no easy task! What’s the difficulty? The difficulty lies in being able to convey that flavor.

When reading picture books to children, it’s usually enough to let the child look at the pictures while the adult reads the words. If the picture book uses simple language for children and the story is particularly interesting, simply reading the story through is generally effective. For example, in the book “Grandpa Will Find a Way,” just read it slowly and don’t speak too fast.

However, to tell the six “Wild Child” books well, you really need some special preparation and practice. What should you practice? — Speaking, learning, joking, and singing. Isn’t that the same as the requirements for performing crosstalk? Hehe, there are some similarities.

For example, “We Want to Be First” tells the story of a group of crickets who are always striving to be number one (it’s a bit of a shame it wasn’t published during the Olympic year, haha). This book can be read directly, but there are so many crickets in the pictures, and they’re talking everywhere, so when reading, I have to find the crickets’ words everywhere. The cricket teacher in the story is particularly emotionally unstable, so imitating his speech takes some effort. Besides speaking, learning and entertaining are also very important when reading this book. Learning means imitating, and entertaining means “playing with you.”

http://landaishu.zhongwenlink.com/home/upload20083/200910232231180.jpg

Illustration of “We Want to Be First”

Let’s talk about “Any Cat Is Useful.” This book tells the story of a seemingly unattractive cat who fulfills his dream of performing Peking Opera. It can also be seen as an extension of the “Peking Opera Cat” story. The book includes a Peking Opera excerpt from “Li Bai Raises His Cup to Invite the Bright Moon,” which would be particularly fun to learn and sing. However, this story isn’t primarily about singing, but about telling. The quotation marks indicate that this isn’t “telling” in the usual sense, but rather about engaging in a stand-up comedy routine. Before discussing this book, listen to a stand-up comedy routine by Liu Baorui to get the feel for it. When telling the story, especially in the later pages, don’t rush; take your time and deliver the punchline at the end.

To sing “A Garden of Green Vegetables Becomes a Spirit” and “Cricket and Grasshopper” well requires some singing skills. The former is easy to learn with standard Beijing-style nursery rhymes, which can be found online. The latter, also a nursery rhyme, is also a Beijing-style drum song, so it’s not so easy to sing. You can find a suitable version online called “Grasshopper and Cricket” and learn to sing it with your child. I’ve found that children learn faster. Both books are incredibly enjoyable if you can sing them well. If you can only read them without singing, the fun is reduced by 60–70%.

It’s said that “The Invisible Horse” requires comprehensive skills, especially the spirit of “bravely performing.” If you take the plunge, this book might be a favorite with children. This book, through a fictional stage play, tells the story of how imaginary horses are portrayed in Peking Opera. A magazine version of the book, published in “Super Baby,” featured only spoken and sung parts by the Peking Opera characters. Honestly, I initially struggled to figure out how to tell this story to children. Xiong Liang must have recognized this problem; he tried reading it to his own daughter and also found it quite difficult. So, in this new version, he added the preface and the book’s narration. (By the way, I’m particularly impressed by Xiong Liang’s spirit and ability to learn, demonstrated in this kind of self-transcendence!) With this approach, the book can be used as a storytelling medium. However, it presents a new challenge for the storyteller: you have to use a combination of narration, spoken and sung parts to tell the story to children. That night, I really gave it my all! Apart from the somewhat unsatisfactory narration, the lines were recited at the top of their lungs and the singing was even more out of tune… Unexpectedly, it was a huge success and was extremely popular with my daughter, who kept shouting “Do it again, do it again.”

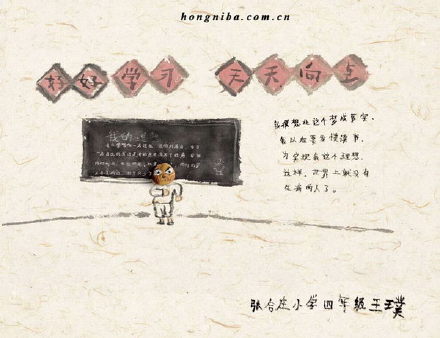

Finally, let’s talk about “My Ideal.” The cover of this book boasts “Works by Xiong Liang and Wang Pu.” Wang Pu is a fourth-grade student at a rural elementary school, and the text in this book is a copy of one of his essays, unchanged. Relatively speaking, this book is short in terms of story content. If you were to read it the usual way, this essay, less than 300 words long, would be finished in the blink of an eye. Of course, that’s not the way to go. Much of the fun in this book lies in the illustrations, allowing you to savor the stories as you read. And just a quick aside, the diverse people of the Five-Colored Earth are also hidden in this book. :)

http://landaishu.zhongwenlink.com/home/upload20083/2009102315627302.jpg

Title page of My Ideal

http://landaishu.zhongwenlink.com/home/upload20083/200910231576895.jpg

Five-color Earth Forum Signature Edition

After a round of “talk, learn, play, sing,” you might think, “Oh, that’s so difficult.” Haha, it’s not that scary. The real secret to telling the stories of these books is: try to relax, don’t take it too seriously, just have fun.

I once heard Xiong Liang discuss the creative process behind “Wild Children.” He explained that the initial inspiration for these stories came primarily from children’s thoughts or outdoor games he played with them. He often traveled alone, meeting children from the mountains and villages, and becoming close friends with some, like the storyteller in “My Little Pony” and the young author of “My Ideal.” When Xiong Liang spoke of the term “wild children,” it was with respect, even a touch of attachment. Playing and breathing in the world like wild children—that, I think, is quite an ambition. Perhaps it was this understanding that allowed Xiong Liang to let go of his artistic baggage in the creation of “Wild Children,” focusing less on their artistic merit and more on whether they could be enjoyed by children. So, you can simply treat these “Wild Children” as fun “toys” to play with your children and do whatever you like.

Okay, that’s all for now. Just a quick note: to celebrate the successful release of the “Wild Child” picture book series, a storytelling session will be held at Hongniba on the afternoon of October 31st. Carrot Inspector and I will be hosting, and we’ll have Xiong Liang himself telling and singing a story. The theme is “Talk, Learn, Amuse, and Sing — Wild Child.” Naturally, there will be a book signing (P.S.: The pages of this book series are made of thicker offset paper, perfect for writing with a brush). Everyone, from 0 to 99 years old, is welcome. Experts in storytelling, learning, amusing, and singing are especially welcome to join us on stage. Hey, upstairs, please!

October 23, 2009 Red Mud

Related links

First a Wild Child, Then a Painter (Reader Original Edition)

Wild Child, Part 6: A Garden of Green Vegetables Becomes a Spirit (Vegetable Version)

“Wild Child” No. 5 “My Ideal” (Composition by Rural Children)

Xiong Liang talks about creation

Talking with Teacher Ajia about the Aesthetics of Picture Books

(Xiong Lei)

Appendix:The birth story of the “full moon cat” — a short note on the red mud reading activity