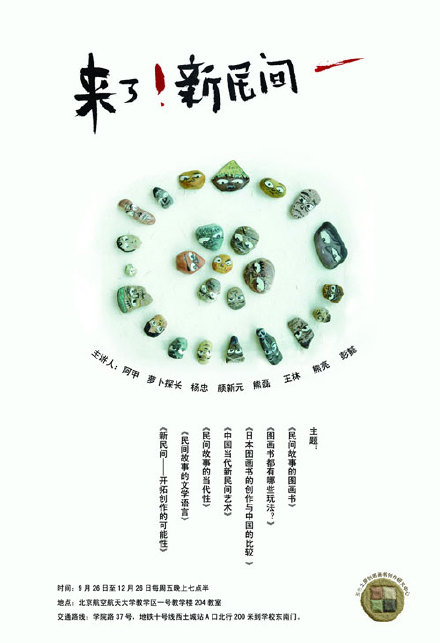

Link:2008 “Five-Colored Soil” China Original Picture Book Annual Forum (September-November, Beihang University)

Last night (October 24th), I attended Professor Yang Zhong’s lecture at Beihang University, which was truly eye-opening. Most discussions about picture books these days focus on storytelling, literary quality, appreciation perspectives, and reading methods, but rarely on artistry or the relationship between visual art and children’s cognition. Professor Yang Zhong’s lecture addressed this gap. I took detailed notes yesterday, but I haven’t had time to organize them all. Here are some of the things that impressed me the most, which I’ve hastily written down in rough order, without any specific categories:

☆

Regarding the current situation of picture books in China, “parents blindly buy books for their children from an educational perspective, ignoring the fact that picture books themselves are an important medium for enriching children’s emotional world, improving their inner personality, and cultivating their aesthetic tendencies.”

☆

In China’s development, comic strips and children’s illustrations were once glorious, and in the 1980s they reached a very high level in some areas. However, in the 1990s, with the popularization of television and the impact of foreign culture, it seemed to come to a sudden halt.

☆

For example, the style of Yan Zhexi’s “The Adventures of Little Cock” (written by He Yi) in the 1960s is really similar to that of “Make Way for the Duckling” (Robert McCloskey, USA), which is said to be influenced by Russian painting style.

☆

I learned that there’s a theoretical book called “New Millennium Image Gala” by Japanese author Masaya Takeda, which specifically studies Chinese comic strips. It’s interesting to note that comic strips used to be called picture books in Shanghai.

☆

Among the original works, I was particularly impressed by Zhao Baishan’s “Secrets of the Ocean” from 1978. Its realistic skill and earnest spirit were touching. I feel that the lack of development of picture books (or children’s illustrations in general) in China is not the fault of the painters.

☆

Modern Western and Japanese picture books place more emphasis on visual integrity, layout, and the integration of images and text. (This may be the biggest difference from comic strips or traditional illustrated stories — my association)

☆

I was also a little surprised to learn that Professor Yang Zhong, a professional researcher in the art field, also focused on comic strips and children’s illustrated stories when analyzing Chinese picture books. I’ve actually thought about this myself before :)

☆

A quote from Mr. Yang Yongqing’s review suggests that Chinese comic strips and children’s illustrations are largely based on folk tales, while too few are based on stories from children’s own lives, resulting in a monotony in variety. Xiong Liang’s formulation of the “new folk” proposed by Wu Se Tu suggests drawing more on real-life children’s stories and incorporating the techniques of folk tales.

☆

Professor Yang Zhong mentioned that picture books in the United States, Britain, and Japan had already become academic research topics in the 1980s. (This is consistent with British researcher David Lewis’s assessment of Britain and the United States.) China is currently just getting started.

☆

The creation of picture books must be combined with life.

☆

Don’t underestimate children’s ability to understand. Children’s understanding is just from a different perspective than adults’.

☆

Meet a very important person: Bruno Munari

Munari (1907–1998)—I’m ashamed to say I’ve never heard of him before.—He was an Italian picture book master. Originally a graphic designer, 3D modeler, sculptor, and art critic, he turned to children’s books after becoming a father, hoping to provide suitable books for his own children.

☆

We watched Mnari’s The Circus In the Mist (1968) together and were deeply moved.

☆

Munari’s understanding of picture books: the content of illustrations must be unified and clear.

☆

The question of what colors are best for children is still under study, and there are many different opinions. Some people think that things with gray tones may be the best for children.

☆

Children’s visual judgments can differ significantly from adults’ imaginations. Japanese researchers once conducted an experiment among children, asking them to choose their favorite from a selection of world-famous paintings. The results surprised many adults: the children preferred Picasso’s “Weeping Woman.”

☆

Before the 1960s, Japanese picture books were mostly in a style that adults considered “cute”, but later they gradually realized (represented by Mr. Naoki Matsui) that picture books should “convey a correct recognition ability” to children; children especially like those “living things”.

☆

In addition, the question of “Is what children like right and good?” is also worth pondering. Parents’ aesthetic sense is also very important.

☆

Japanese picture books have gone through several periods of development: the 1960s, the period of building a new children’s culture; the 1970s, the heyday; the 1980s, the period of results and development; and from the 1990s to the present, questioning the essence of picture books.

☆

Since the 1960s, picture books have strived to convey information to children “intuitively and accurately” (exemplified by Nao Matsui’s Fukushikan). For example, a picture book about trucks wouldn’t depict the vehicles in cartoonish or cute ways, but rather “describe the relationship between the trucks, people, and the streets.” This emphasis on the overall aesthetic impact of picture books on children.

☆

Take Fukushikan’s latest “Japanese Masterpieces” and “World Masterpieces” series of picture books, for example. Printing has reached a high level, achieving “dot-free” and “zero DPI” printing, maximizing the beauty of the original artwork. Of course, the price is also high, at around 140 RMB per book.

☆

In the 1960s, animal images were prevalent (previously cute children were the main focus), and they placed more emphasis on children’s individuality and mischievous nature.

☆

In the 1970s, mothers’ groups became very important and gave a great impetus to the development of picture books.

☆

“The Cat Who Lived a Million Times”, published in the 1970s, is the first picture book in Japanese history about death.

☆

In 1980, Cho Shinta’s Cabbage Boy was published. It was “written entirely from a child’s perspective” and “reproduced the child’s imaginary world.”

☆

The diversity of Japanese picture books, classified into: folk tradition, fairy tales; intellectual education, education; children’s; pop (three-dimensional books); textless; e‑books.

☆

The creation of picture books combines education, artistry and entertainment.

☆

Next, everyone admired the work of three classes of picture book creation students taught by Teacher Yang Zhong. Although I’ve seen some of these before, this systematic and comprehensive review was truly astonishing. I was particularly struck by the creativity and professionalism displayed by the students. Although many of these works are still incomplete, they already transcend the typical children’s illustrations and storytelling, creating a refreshing experience. In particular, the visual design and use of color in some of these works have a distinctly children’s picture book feel, making it hard to believe they were created by such young students. I used to think that illustrating for children primarily relied on specific childhood experiences, but now it seems that professional training is truly possible. At the very least, through professional training, we can systematically understand the accumulated experience of others.

☆

Finally, everyone enjoyed “The Birth of the Forest,” “Dream-Eating Tapir,” and “Listen to Grandma” again. Teacher Yang is very proud of the upcoming publications of her three students. Furthermore, compared to their coursework, these works are truly remarkable, demonstrating remarkable progress! Congratulations!

Argentine Primera División (October 25, 2008)

Impressions after the lecture “Comparison of Japanese Picture Book Creation and Chinese Picture Book Creation”