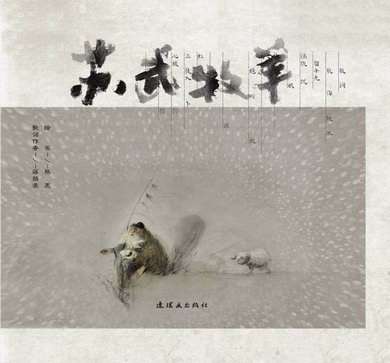

The original picture book “Su Wu Shepherding Sheep” was illustrated by Xiong Liang and published by Comic Book Publishing House in 2008.

It is actually a song with lyrics by Jiang Yintang and music by Tian Xihou.

I’ll sing it first, sorry for the poor performance :)

Link:Listen to flute music online: Su Wu Shepherding Sheep

Su Wu herding sheep on the North Sea coast in the snow and ice

Where is the North Sea? The North Sea is actually a large lake, which is today’s Lake Baikal in Russia. During the Western Han Dynasty, it was under the control of the Xiongnu.

http://www.hongniba.com.cn/bookclub/demo/qingyun/suwu08.jpg

Complete Map of the Western Han Dynasty (Scanned from Concise Atlas of Chinese History)

Su Wu’s family was in Chang’an, yet he had to go to such a remote place with ice and snow to herd sheep. No one would be willing to do that, but Su Wu went anyway. That was around 100 BC, or 2,100 years ago.

http://www.hongniba.com.cn/bookclub/demo/qingyun/suwu03.jpg

Today, Lake Baikal is a beautiful and fertile lake, a popular tourist destination. However, 2,100 years ago, for a Han Chinese like Su Wu, life was a difficult one. He was detained and exiled there, like a prisoner or a slave. He was completely alone, without a single Han Chinese by his side.

Detained for 19 years

Su Wu was held captive by the Xiongnu for nineteen years, a somewhat unlucky fate. He was a kind man, and the Han Emperor Wu of Han greatly favored him and placed him in important positions. When he arrived in the Xiongnu, the Xiongnu king, Chanyu, also favored him and tried every possible means to subjugate him. However, Su Wu suffered instead.

In the first year of the Tianhan era (100 BC), Su Wu was promoted by Emperor Wu of Han to the rank of General of the Central Guards (chief of the imperial guards) and sent on a diplomatic mission to the Xiongnu. Prior to this, Su Wu held a low-ranking position, serving as a mere guard in the emperor’s inner circle, and had achieved no significant feats. He gained this position because his father, Su Jianli, had military achievements, rising to the rank of prefect and the title of Marquis of Pingling. This promotion was also due to Emperor Wu’s fondness for him. Coincidentally, he was 41 years old that year, which also coincided with Emperor Wu’s 41st year on the throne.

Logically, Su Wu’s assignment to the Xiongnu was a welcome one. Relations between the Han and Xiongnu had been strained for some time. Due to misunderstandings, friction, and a rebellious nature, each side had detained some of the other’s envoys. That year, the Xiongnu Chanyu, Qiedihou, had just come to power and, out of a sense of righteousness, promptly sent the Han envoys back. Emperor Wu of Han was overjoyed, believing the new Chanyu was a man of integrity. So, he, too, sent envoys to return the detained Xiongnu envoys. Furthermore, he also prepared generous gifts for the Chanyu Chanyu. Who wouldn’t be happy about such a mutually beneficial situation? Therefore, Su Wu’s assignment was supposed to be a great one, earning him a promotion and facilitating goodwill for both sides. So, accompanied by two deputies and over a hundred soldiers, he set off with the detained Xiongnu envoys, escorting gifts and making friends along the way. It seemed his trip was bound to be highly rewarding.

But things went against their wishes. The problem started with the generous gifts. According to the Han people’s understanding, courtesy is reciprocity, and when giving generous gifts, it is natural to have something in return. But the Xiongnu people didn’t think so. Seeing Emperor Wu of Han so polite, the Chanyu became proud, and seeing that the other party was so rich, they couldn’t help but want to find an opportunity to grab some more. We always say “the more courtesy, the less blame”, but that only applies to the Han people. Being polite and respectful to everyone is fine for family members, but sometimes it will cause problems for outsiders. In short, the Chanyu kept delaying and didn’t give a reply, that is, a reply or a gift, so Su Wu and his companions had no choice but to stay there, waiting, waiting…

Finally, something happened. One of Su Wu’s lieutenants, Zhang Sheng, was embroiled in a Xiongnu conspiracy, participating in the assassination of Prince Gou, Wei Lu. Wei Lu, a native of the Hu people, had served as an official in the Han Dynasty and an envoy to the Xiongnu. He later defected to the Xiongnu and became a close confidant of the Khan. This incident is a long story, but simply put, Zhang Sheng was embroiled in a situation completely unrelated to his mission. Regardless of his initial intentions, he ultimately committed a major diplomatic offense.

The assassination attempt failed, and the mastermind was arrested. Zhang Sheng hurried over to tell Su Wu the truth. He had to tell the truth because he knew he would be betrayed soon. Su Wu was shocked after hearing this, and in desperation he was about to draw his sword and commit suicide. This was Su Wu’s first suicide attempt. It was called “the first time”, so of course it was unsuccessful. Zhang Sheng and another deputy, Chang Hui, hugged him. Why did Su Wu want to commit suicide as soon as he heard about this? Because he was a diplomat who understood the rules of diplomacy very well. He knew that he was in the wrong in this matter, and the Huns would definitely hold on to it and make use of it. At that time, his personal safety would be small, but the country’s face would be lost. As the person in charge of this mission, he wanted to die to apologize.

As expected, Zhang Sheng was arrested soon after. The Chanyu thought this was a good opportunity, so he asked Wei Lu to find a way to use this as an excuse to subdue Su Wu. On the one hand, he wanted to embarrass the Han Dynasty, and on the other hand, the Chanyu still liked Su Wu. The Chanyu sent Wei Lu to arrest Su Wu for trial. When Su Wu heard about it, he immediately drew his sword and committed suicide. This was Su Wu’s second suicide attempt. This time he almost succeeded. At that time, he was only with Chang Hui. Su Wu explained to Chang Hui that this was an apology to his country. Chang Hui did not dare to stop him this time, because he also understood the reasoning. It was extremely humiliating for a diplomat to be arrested and tried. So Su Wu really slit his throat and almost died. Fortunately, Wei Lu arrived in time, personally picked up Su Wu, dug a pit, drained the blood, and found a concubine. After a long time of hard work, he finally rescued Su Wu.

From then on, the Chanyu became even more fond of Su Wu. You see, this is the nature of the Xiongnu: if you’re polite, they’ll look down on you, thinking you’re weak and easy to bully; if you’re desperate, they’ll respect you and be polite. While Su Wu was recovering from his injuries, the Xiongnu took exceptional care of him. King Wei Lu also visited him daily, personally caring for him and constantly trying to get close to him.

After Su Wu’s wounds healed, Wei Lu began to make arrangements again. He arranged a joint trial, this time inviting Su Wu to the bench to watch Wei Lu interrogate the prisoners, including Zhang Sheng. This scene was clearly for Su Wu to watch. Wei Lu first ordered the mastermind to be brought in and beheaded on the spot. He then called Zhang Sheng and wanted to behead him as well, but Zhang Sheng, fearing death, surrendered on the spot. Wei Lu threatened Su Wu, but Su Wu remained unmoved. Seeing that hard tactics didn’t work, Wei Lu tried soft tactics, using himself as an example to persuade Su Wu to surrender. He also said that if you surrender, we will become sworn brothers, but if you don’t, you will never see me again. Su Wu then cursed Wei Lu: Who do you think you are? You are an ungrateful traitor who is seeking fame and fortune. Who would care about you? If you have the guts, kill me. Nanyue, Wan, and Korea had all killed Han envoys in the past, and all suffered devastating retaliation. The Xiongnu had never killed a Han envoy. If you kill me today, the disaster for the Xiongnu will begin from now on. Wei Lu was so frightened that he had to give up.

Upon hearing Wei Lu’s report, the Chanyu, far from being angry, was overwhelmed with admiration for Su Wu. He was determined to subjugate Su Wu, disregarding all diplomatic rules and the Han Dynasty’s military threat. Thus began Su Wu’s captivity with the Xiongnu.

The above story is primarily based on Ban Gu’s “Book of Han,” with reference to relevant sections of Sima Guang’s “Zizhi Tongjian.” Both of these historical texts were written by Han Chinese. I’m curious about how the Xiongnu would have written about this period of history—if they actually did. While I certainly admire Su Wu for his remarkable achievements, I also find the Chanyu and Wei Lu to be lovable individuals, especially the Chanyu, who deeply admired heroes. The Chanyu, convinced of Su Wu’s exceptional heroism, was determined to gain his allegiance, even at the cost of a fortune. This is a truly heroic act. However, from a Han perspective, it seems outrageous and unreasonable.

Thirsty drinks snow, hungry swallows felt

There is also a version written as “thirsty drinking blood”, which is also written in this picture book. Although it can be explained in another way, I think it is better to use “thirsty drinking snow”. It has a source and the story feels more real.

The Book of Han records: “The Chanyu became increasingly eager to surrender, so he imprisoned Wu and placed him in a large cellar, denying him food or drink. When it began to snow, Wu lay down and gnawed on snow and its hair, swallowing it, and survived for several days.”

The Chanyu was completely helpless against Su Wu. Neither threats nor bribes worked; he couldn’t let him go, nor could he kill him. He had no choice but to imprison him in a large cellar, depriving him of food and water, to see how long he could endure. While someone could endure a few days without food, they couldn’t endure without water. The Chanyu probably thought Su Wu might give in and surrender. If he didn’t, he would have starved to death, not been killed by the Huns. In essence, it was the same thing.

But a few days later, the Xiongnu discovered that Su Wu was still alive. It turned out that it was snowing heavily at the time, and Su Wu chewed handfuls of snow when he was thirsty, and gnawed on the wool felt wrapped around him when he was hungry. This is how he tenaciously survived.

The Xiongnu believed Su Wu to be a god and, no longer able to hold him captive, sent him to the North Sea to herd sheep. They left him there without food, leaving him to fend for himself. Yet Su Wu managed to survive, sometimes even digging into burrows where wild mice hid their food and snatching millet from them to satisfy his hunger.

Some may ask, considering Su Wu attempted suicide twice, why did he later fight so tenaciously for survival? Are there any contradictions between his actions? I believe there are none. Su Wu’s first two suicide attempts were not for himself, but for his country. As an envoy, he risked his life when his country was threatened with humiliation, embodying the saying, “Better to die in glory than live in disgrace.” It was precisely because of Su Wu’s attitude that the Xiongnu dared not make a fuss about this matter, and their subsequent actions were primarily directed at Su Wu personally. The Chanyu completely disregarded diplomatic protocol and no longer treated Su Wu as an envoy. Instead, they sought to force him to surrender and subjugate him, putting him in a desperate situation, completely isolating him, and sapping his fighting spirit. At this point, Su Wu was incredibly stubborn, determined to survive as long as there was a glimmer of hope!

As an individual, Su Wu can endure humiliation and endure it, just because of his belief, his mission, and his commitment, he can survive in an extremely humble way!

This is what makes a great hero!

Sleeping Alone in the Wild Night

Both this song and this picture book allow us to see a stubborn, lonely soul in the wilds of nature. The sky is his tent, the earth his bed, even the sheep huddle together, and only the bright moon listens to his silent confession…

What is this lonely man thinking?

http://www.hongniba.com.cn/bookclub/demo/qingyun/suwu04.jpg

The dream of the Han Dynasty is in my heart, and my old homeland is in my heart

After going through so much hardship, I still haven’t returned

He was naturally thinking of his homeland, his homeland. How do we know? Look at what he was holding in his arms: a stick with a row of fur tassels tied to it. From a distance, it looked like a flag when blown by the wind. Su Wu leaned on it while herding sheep all day, held it when he sat down, and even kept it close at hand when he went to sleep.

http://www.hongniba.com.cn/bookclub/demo/qingyun/suwu05.jpg

This is no ordinary stick or flag; it’s called an envoy, a symbol of the country and its mission. During his long, lonely wait by the North Sea, it was Su Wu’s only old acquaintance who remained with him, and it held all his faith.

The tassels of this kind of envoys were made of yak tails, hence the name “jiemao”. During the Spring and Autumn Period, Prince Ji of Wei was on a diplomatic mission to Qi. On the way, he was ambushed by bandits sent by his father. The envoy’s tassels he was holding were made of white hair, hence the name “baimao”.

Su Wu wasn’t the first person to herd sheep while on a diplomatic mission. Before him, Zhang Qian had also spent over ten years herding sheep while holding a diplomatic mission in the Xiongnu. However, Zhang Qian’s circumstances were different. He was on a mission to the Western Regions, preparing to unite with the Xiongnu to attack the Xiongnu. Therefore, when captured by the Xiongnu, he could be considered a prisoner of the enemy state, and being forced to herd sheep as a slave did not violate diplomatic rules. Su Wu was truly wronged. He was clearly an envoy to the Xiongnu, and as the saying goes, “When two countries are at war, envoys are not executed.” Yet, he was also forced to herd sheep as a slave, and his mission lasted for nineteen years!

Because he always held on to this envoy, after a few years, the hairs on it fell off, and there was still no hope of returning home.

Sitting alone in the cold, I hear the sound of the Hujia, and my ears ache.

Sitting alone in the extremely cold wilderness, still with my back straight, the mournful and tragic sounds of the Hujia music came to my ears from time to time. I don’t know if it was in my ears or in my heart, it was so painful!

The meaning of this line likely comes from “Li Ling’s Reply to Su Wu,” a book some consider a forgery. Regardless, it’s a well-written piece of writing, equally poignant and moving. One passage reads: “The land of the Hu people is covered in black ice, the borderlands are shattered, and all I hear is the mournful sound of a desolate wind. In the cool ninth month of autumn, the grass outside the Great Wall withers. Sleepless at night, I listen intently to the echoing sounds of the Hujia. The herds of pasturing horses neigh mournfully, the whistling of flocks, the sounds of the border rising from all directions. Sitting in the morning, listening to them, I find myself shedding tears.”

Li Ling is a renowned figure in history. I remember listening to the storytelling of “The Generals of the Yang Family” as a child. In the story, Yang Linggong was defeated and trapped, unable to break out. He was led by some mysterious force to Li Ling’s tomb. Unwilling to follow Li Ling’s example and surrender to the foreign powers, Yang Linggong crashed into his head and died in front of Li Ling’s stele. While this isn’t necessarily the case in official history, the storytelling naturally uses Li Ling as a metaphor.

In the “History of the Han Dynasty,” the deeds of Li Guang, Li Ling, Su Jian, and Su Wu are recorded in the same biography, as Li Ling was Li Guang’s grandson and Su Wu was Su Jian’s son. Among Li Guang’s descendants, only Li Ling was the most promising, inheriting his grandfather’s skills: exceptional martial arts, superb archery, and a seasoned warrior. Li Ling and Su Wu remained close friends.

In terms of skill and martial prowess, Li Ling was undoubtedly superior to Su Wu. However, in the eyes of later generations, Su Wu is a towering hero, while Li Ling is riddled with blemishes, even storytellers and children can use him to make fun of him. The only difference between the two is that Li Ling surrendered to the Xiongnu; Su Wu preferred death to surrender.

In 99 BC, the year after Su Wu was held captive by the Xiongnu, Li Ling led his army in a campaign against the Xiongnu. The Han army suffered a crushing defeat this time, as the commander, Li Guangli (no relation to the Li Guang family), was a mediocre commander with questionable character. But after all, he was the younger brother of the emperor’s favorite concubine. Unwilling to follow such a commander, Li Ling requested to lead a detachment of 5,000 infantry archers deep into Xiongnu territory. With the main force of the Han army routed and isolated, Li Ling led his troops into battle against a force of 100,000 Xiongnu troops led by the Chanyu himself. Fighting while retreating, he repelled numerous Xiongnu attacks and killed nearly 10,000 enemy soldiers. Finally, they were within a hundred miles of the Han frontier, but with no one to rescue them, Li Ling’s troops, exhausted by ammunition and food, were routed by the Xiongnu. Despite risking his life to remain behind, Li Ling was unfortunately captured. Although Li Ling dealt a heavy blow to the Xiongnu army and killed so many Xiongnu people, the Chanyu still admired and respected this general, so he accepted Li Ling and made him a king in the Xiongnu. Later, he entrusted him with important troops and tasks.

The Chanyu had his reasons for liking Li Ling, but how could Li Ling, a Han general and grandson of the renowned Li Guang, surrender? According to Li Ling himself, he had other plans: to endure humiliation and survive, waiting for an opportunity to return to the Han court. However, Li Ling’s surrender deeply angered Emperor Wu of Han, who first imprisoned Li Ling’s entire family and later executed them all, even castrating Sima Qian, who had spoken well of Li Ling. Ultimately, Li Ling remained with the Xiongnu.

Li Ling and Su Wu were good friends, and logically, Li Ling should have visited Su Wu upon his arrival in the Xiongnu. However, he never went, primarily because he knew Su Wu’s character and felt embarrassed to meet him. Years later, the Chanyu heard of their relationship and sent Li Ling to persuade Su Wu again. It turned out that the Chanyu still cared about Su Wu.

Su Wu was delighted to see Li Ling. After all, they were old friends, and reuniting in a foreign land brought them a shared passion. For the first few days, they drank and chatted, but when Li Ling tried to persuade Su Wu to surrender, Su Wu sternly refused, threatening to die. This filled Li Ling with shame, and he sighed, “Alas, righteous man! The crimes of Li Ling and Wei Lu are known to heaven!”

For a long time, Li Ling dared not see Su Wu. However, Li Ling remained a loyal friend. He asked his wife to send someone to take care of Su Wu, leaving him livestock and a tent. He later arranged for Su Wu to marry a Xiongnu woman who greatly admired him. With Li Ling’s help, Su Wu’s life in captivity was relatively prosperous and stable, and he began to feel a sense of home.

http://www.hongniba.com.cn/bookclub/demo/qingyun/suwu06.jpg

The geese are flying south, to whom should I send this letter?

White-haired girl leaning against the wooden door

Red makeup guards the empty curtain

For nineteen years, Su Wu’s longing for home and his family never ceased, which was also an important reason that kept him alive.

When Su Wu was sent as an envoy to the Xiongnu, his father had passed away, but his mother was still alive. He had an older brother, a younger brother, and two younger sisters at home. His wife gave birth to a son and two daughters for him.

After Su Wu was exiled to the North Sea, he lost all contact with his family. Every year, when he saw the geese flying south, he couldn’t help but think of his family, wishing he could have wings. What he missed most were his gray-haired mother and his wife, who had been with him through thick and thin. He imagined that they were all waiting for him anxiously.

After seeing Li Ling, he naturally asked about the situation of his family. When he heard it, he was even more sad.

Li Ling told him: “Since you left, your elder brother committed a minor offense while helping the emperor out of his carriage and committed suicide. Your younger brother, fearing the consequences of his actions, accidentally killed a eunuch during an argument and committed suicide by poisoning. Your mother died shortly after your mission, and I attended her funeral at Yangling. Your wife was still young, and I heard she remarried. Only your two younger sisters, your son, and your two daughters remain in your family. It has been over ten years since I left, and I have no idea how they are doing now, whether they are dead or alive.”

How did Su Wu, who had endured more than ten years of hardship in the North Sea, feel when he heard this news?

Alas! The great sorrow and suffering of life, how helpless!

At three o’clock in the morning, I entered a dream, uncertain about safety and danger

http://www.hongniba.com.cn/bookclub/demo/qingyun/suwu01.jpg

In this state of mind, how could I sleep? My own safety, the fate of my loved ones, were all unknown and unpredictable…

Li Ling also included this passage in his speech: “Furthermore, Your Majesty is old, and the laws are inconsistent. Ministers have been executed without cause, and dozens of families have been exterminated. The safety of the court is uncertain. Who would you serve?” His point was that the Emperor (Emperor Wu of Han) was old, and the laws were inconsistent. Today, he executed a minister, tomorrow, another family. The court was in a state of panic, and no one knew their own safety. Who would you serve?—Of course, this was an argument used to persuade Su Wu to surrender, but it certainly held true when it came to Emperor Wu of Han’s later years.

Under such circumstances, could Su Wu be moved?

Sad and hopeless, but still not without its flaws

Yes, all kinds of experiences, hardships, shattered hopes, bad news about his family, and negative news about his motherland have wrapped Su Wu up layer by layer. He feels extremely sad and has lost all hope.

However, even so, Su Wu, as an envoy of the Han Dynasty, still held the banner of honor and remained loyal to his country. He always adhered to his beliefs, his mission, and his promise!

Later, probably in 87 BC, Li Ling came to Haishang again and told him that the emperor had passed away. This man, who almost never shed tears, faced south and wailed for days and nights until he vomited blood…

I think Su Wu’s crying was not just about crying for the emperor as a minister. His sorrow far surpassed all of this. Because of Emperor Wu’s death, the envoy would never have the chance to return to report to him. He had endured for 13 years for that day! From then on, his promise would no longer be fulfilled.

From now on, what is the point of continuing to live?

Ram not yet lactating

Unexpectedly, he finally survived and returned with the Han envoy

http://www.hongniba.com.cn/bookclub/demo/qingyun/suwu07.jpg

The last line of the lyrics seems quite puzzling on the surface: the ram had not yet given birth to a lamb, but unexpectedly it was finally alive and returned to its homeland with the Han Dynasty envoys during its lifetime.

How could a ram give birth to a lamb? Indeed, it couldn’t. This was a rather unkind joke played by the Xiongnu on Su Wu. Back then, the Chanyu exiled Su Wu to the North Sea to herd sheep, specifically instructing him to herd only rams and declaring that unless the rams gave birth to lambs, Su Wu would never be able to leave.

How could there be such a miracle in the world?

But another “miracle” happened. Thanks to this “miracle”, Su Wu finally returned to his homeland.

After Emperor Wu of Han’s death, Emperor Zhao of Han ascended the throne, and Huo Guang (Huo Qubing’s half-brother), the minister entrusted with the care of the young emperor, assumed great power. Huo Guang desperately wanted Su Wu to return to China. The Xiongnu’s old Chanyu had also died, leaving the nation fragmented. The new Chanyu (the old Chanyu’s son) sought peace with the Han dynasty, and Huo Guang seized the opportunity to demand Su Wu’s return. However, the Chanyu claimed that Su Wu had died several years earlier, herding sheep in the North Sea. His deputies and attendants had also passed away. The Han envoys were left with no other options but to return home to report.

Huo Guang, unwilling to give up, sent another envoy to the Xiongnu. This time, Su Wu’s deputy, Chang Hui, managed to meet with the Han envoy, told him the truth, and secretly gave him a plan. The Han envoy once again demanded Su Wu’s return from the Chanyu, who again lied, saying, “Su Wu is dead.” The Han envoy then solemnly explained that Emperor Zhao of Han had recently shot down a wild goose while hunting in Chang’an. Tied to the goose’s leg was a piece of silk with a handwritten letter from Su Wu, stating that he was still alive and herding sheep in the North Sea. The Chanyu was stunned for a moment, then sighed, “If even birds are moved by Su Wu, what else can we say?” He then apologized to the Han envoy and arranged to retrieve Su Wu and his men and send them back to China.

This “miracle” is the last picture in the picture book “Su Wu Shepherding Sheep”.

http://www.hongniba.com.cn/bookclub/demo/qingyun/suwu02.jpg

In the spring of the sixth year of the Yuanshi era (81 BC), Su Wu and his companions returned to Chang’an. There were more than a hundred of them when they left, but only ten returned. Su Wu was 41 years old when he left, but his hair and beard were completely white when he returned.

The streets of Chang’an were deserted, and everyone rushed to see Su Wu.

When Su Wu came before Emperor Zhao of Han with the bare envoy, even the emperor could not help shedding tears. He said to Su Wu, “This envoy was entrusted to you by the late emperor. Take it to the Taimiao and offer sacrifices. Then you can report back there and make him happy.”

Although Su Wu experienced many hardships, he remained strong and lived to be over 80 years old. He died in 60 BC.

Although he held a low official position during his lifetime, he was revered by everyone in the court and treated like a national treasure. His son, implicated in a palace rebellion, was executed the year after he returned to China. Later, the emperor, sympathizing with his loneliness in his later years, offered to redeem his son, born during his time in the Xiongnu.

When Su Wu returned to his country, the child was about to be born. He could not bring the child’s mother back with him because even Su Wu himself was just a slave when he was herding sheep, let alone his wife. The child’s mother asked Su Wu to choose a name for the child before leaving. Su Wu said, if it is a boy, he will call him Tongguo, if it is a girl, he can decide for himself.

Sure enough, the baby was a son, named Su Tongguo.