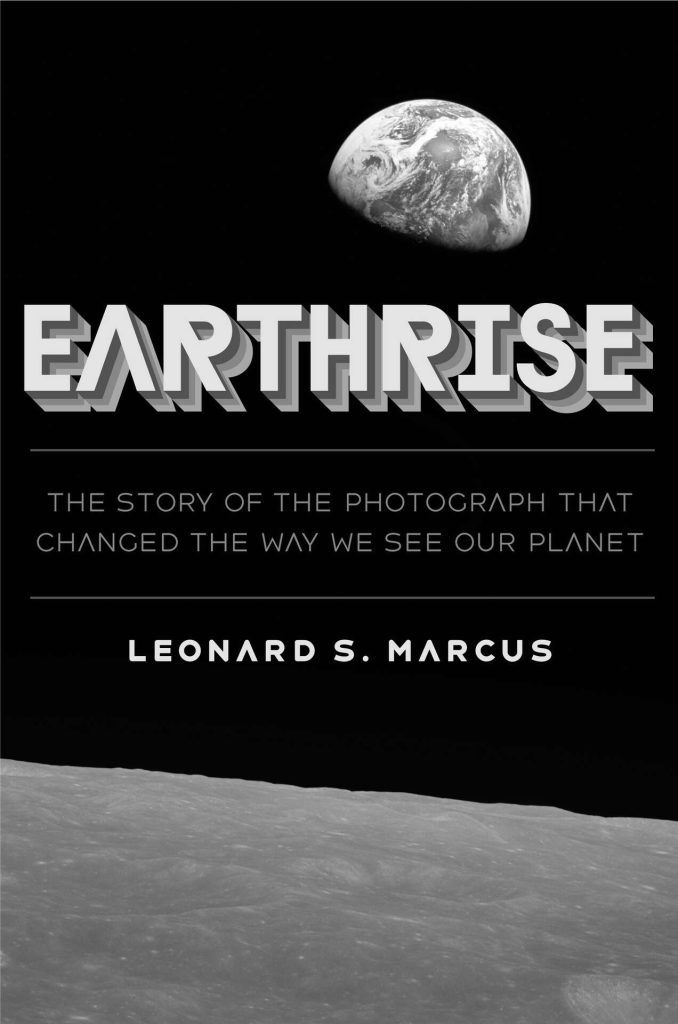

I finished reading a new book by Leonard S. Marcus over the weekend: “Earthrise: The Story of the Photograph That Changed the Way We See Our Planet”

This book was just released in the U.S. on March 4, 2025. It’s available on Kindle, and the title could be translated into Chinese as 《地球升起:一张改变人类视野的照片》. The term Earthrise is quite interesting — it parallels Sunrise and Moonrise, which would suggest translating it as “地出” (like “日出”), but that sounds odd. Translating it as “地球崛起” (like Rise of the Planet of the Apes) would be strange too. So I’d say just go with “地球升起,” which reflects the original name of the iconic photo featured on the cover.

As a children’s book historian, Marcus has written several history books for young readers. Earthrise follows the same narrative approach as his previous work, “Mr. Lincoln Sits for His Portrait” (2023) — using a single famous photograph as an entry point to explore the deeper historical context behind it.

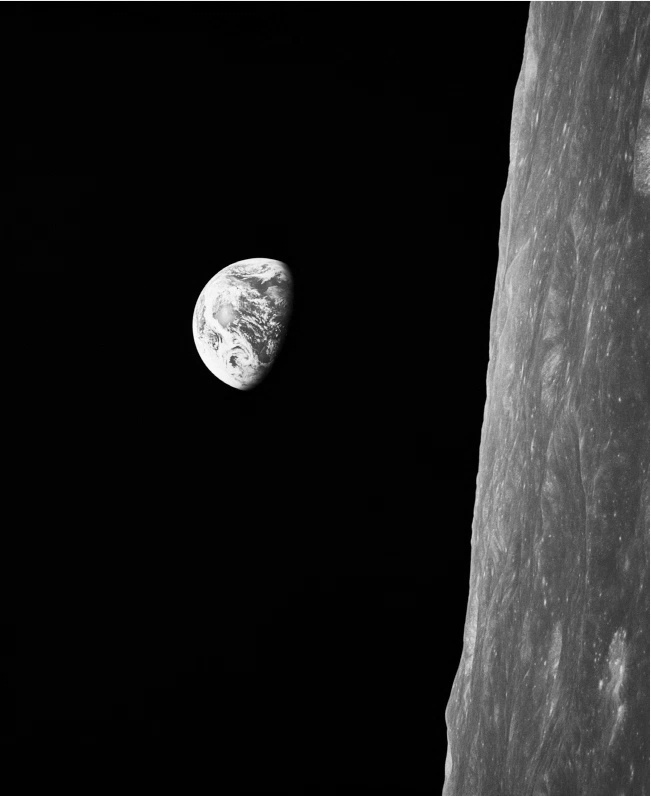

To put it simply, Earthrise tells the story of the iconic photo taken on Christmas Eve, 1968, during the Apollo 8 mission by astronaut Bill Anders as he orbited the Moon. This photo shows the Earth rising over the Moon’s horizon — one of the most consequential and widely viewed images in human history. Marcus unpacks the story behind this photo, combining vivid details, historical context, and personal perspectives to reveal how it changed humanity’s understanding of our place in the universe.

Marcus is a master storyteller. He opens the book with a compelling idea: this photo changed how we see ourselves and our planet. From there, he skillfully unravels a narrative full of tension and conflict — starting with the Cold War space race, including the Soviet Union’s launch of the first satellite, Sputnik; Yuri Gagarin becoming the first human in space; and President Kennedy’s declaration of the Moon landing goal. Marcus maintains a brisk, engaging pace, punctuating the narrative with rare historical images and detailed accounts of the personal sacrifices made by the astronauts and their families.

Interestingly, Marcus begins the book by referring to the “Sputnik moment” — a term that has recently resurfaced in the wake of DeepSeek’s success. Some Western media outlets have described DeepSeek’s breakthrough as a new “Sputnik moment.” But what does this really mean for humanity? Marcus’s account of the original “Sputnik moment” invites us to reflect on how technological rivalry can drive both competition and cooperation — just as the Cold War space race eventually gave way to space collaboration in the 1970s.

How exactly did Earthrise change humanity’s view of the world — even our worldview? I recall that a global historian once suggested that we could try to rewrite human history from the perspective of standing on the Moon and looking back at Earth.

Bill Anders, the astronaut who took the iconic photo, famously said: “We came all this way to explore the Moon, and the most important thing is that we discovered the Earth.” This was a completely new perspective. For the first time, humanity saw Earth not as a vast, endless expanse — but as a small, fragile, and beautiful planet. It inspired humility and awe.

Marcus also pointed out that the “Earthrise” photo made people feel the uniqueness and preciousness of the Earth. The visual impact of viewing the Earth from the lunar orbit prompted people to have a strong “home consciousness” and rethink the definition of “home”. Another astronaut, Jim Lovell, could completely cover the Earth by blocking the window with his fingers. This simple action made him deeply feel the smallness and loneliness of the Earth:

” Just think, over five billion people, everything I ever knew was behind my thumb.”

Earthrise is not just a photograph; it’s a metaphor. It reminds humanity that we are all passengers on “Spaceship Earth,” a fragile and limited vessel that we must protect together. The idea of “Spaceship Earth” sharpened humanity’s awareness of limited resources and environmental vulnerability. It reinforced the idea that we are not just citizens of individual nations, but members of a shared global community with a collective responsibility.

One of my favorite lines from the book comes from Jim Lovell’s realization: “Then I remembered a saying I often heard: ‘I hope I go to Heaven when I die.’ I suddenly realized that I went to Heaven when I was born! I arrived on a planet with the proper mass to have the gravity to contain water and an atmosphere, the essentials for life. I arrived on a planet orbiting a star at just the right distance to absorb that star’s energy—energy that caused life to evolve in the beginning.”

Yes, people on Earth imagine that Heaven is such a wonderful place, but in fact, we have been in Heaven since the moment we were born!

Many people think that the Earth is not so good anymore and are ready to migrate to other planets, but think about it, which planet is more suitable for “Earthlings” than Earth? Instead of trying to migrate, it is better to try not to destroy the Earth, right?

Having followed Marcus’s work for some time, I think the core message of Earthrise is this: Earthrise is not just a famous photograph — it’s a symbol that reminds humanity to re-evaluate the planet we inhabit. It reveals Earth’s isolation and uniqueness in the universe and challenges us to embrace a mindset of global care, peace, and sustainability.

Think about it, if people stay in a village for their whole lives, the people in the village on the other side of the river may be “enemies”. But if you run a thousand kilometers away and look back, the people in the next village are “fellow villagers”. When fellow villagers meet, their eyes are filled with tears. If people stay in the same country for their whole lives, is there a similar situation? When we have the opportunity to turn a few somersaults and run to space hundreds of thousands of miles away, the people in the “enemy country” become neighbors and fellow villagers. When we meet, won’t our eyes be filled with tears?

How do we see the world, how do we see ourselves? — It depends on where you stand.

Finally, I’d like to note the book’s dedication (which I almost missed): “In Memory of Amy Schwartz—Shining Light, Beautiful Spirit”

Amy Schwartz (April 2, 1954 – February 26, 2023) was Marcus’s late wife. The dedication carries a quiet yet profound sense of loss and remembrance — a reminder that, just as humanity must cherish the Earth, we must also treasure the people and memories that give meaning to our lives.

Ajia written on March 10, 2025