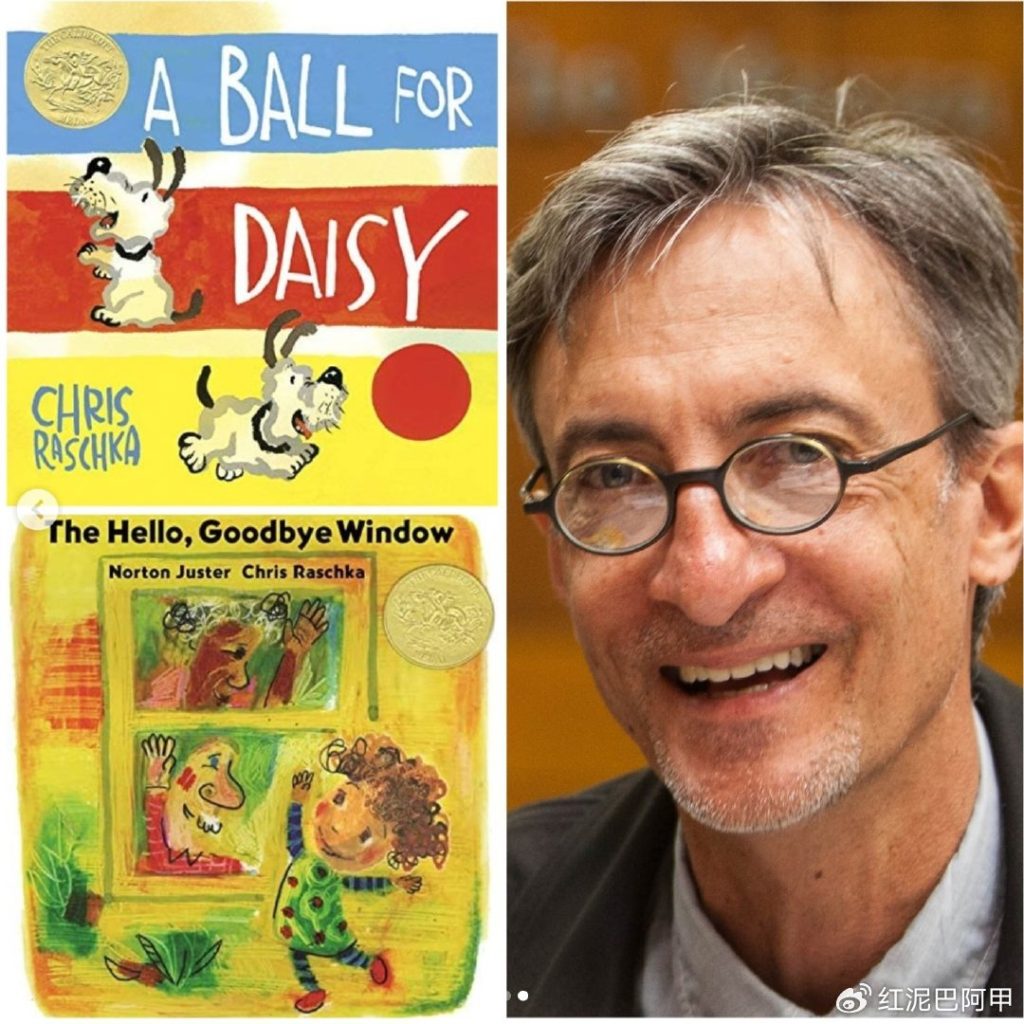

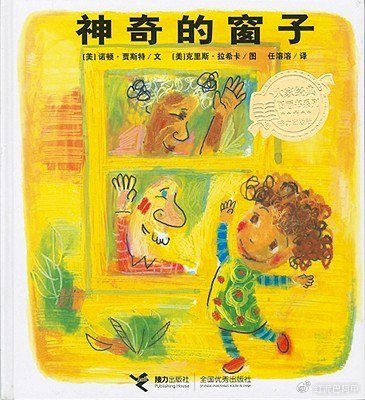

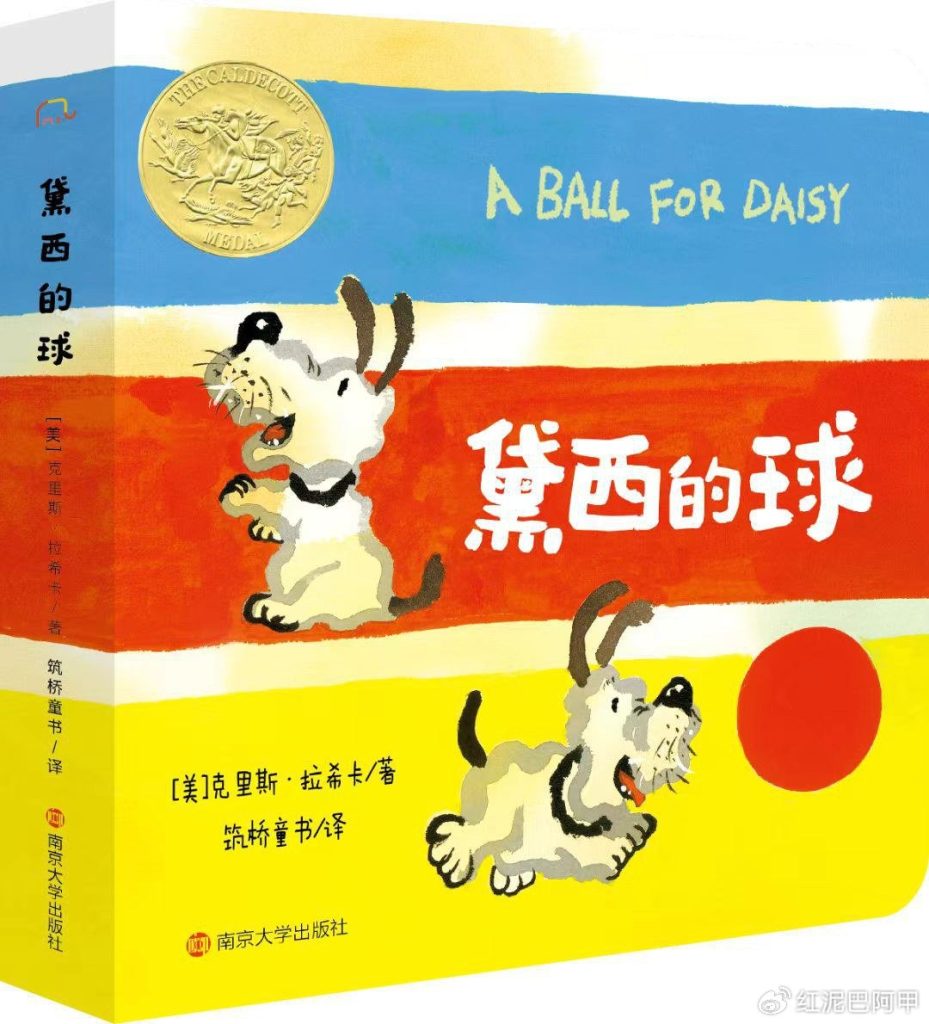

American picture book artist Chris Lasica has twice won the Caldecott Medal for his books “The Magic Window” and “Daisy’s Ball,” and has been nominated for the Hans Christian Andersen Award for International Illustrator more than once. However, Chinese readers seem less familiar with him. This may be due to his penchant for experimenting with new media, themes, and styles, making it difficult for people to identify him through his recognizable body of work. Each of his books feels like a fresh creation.

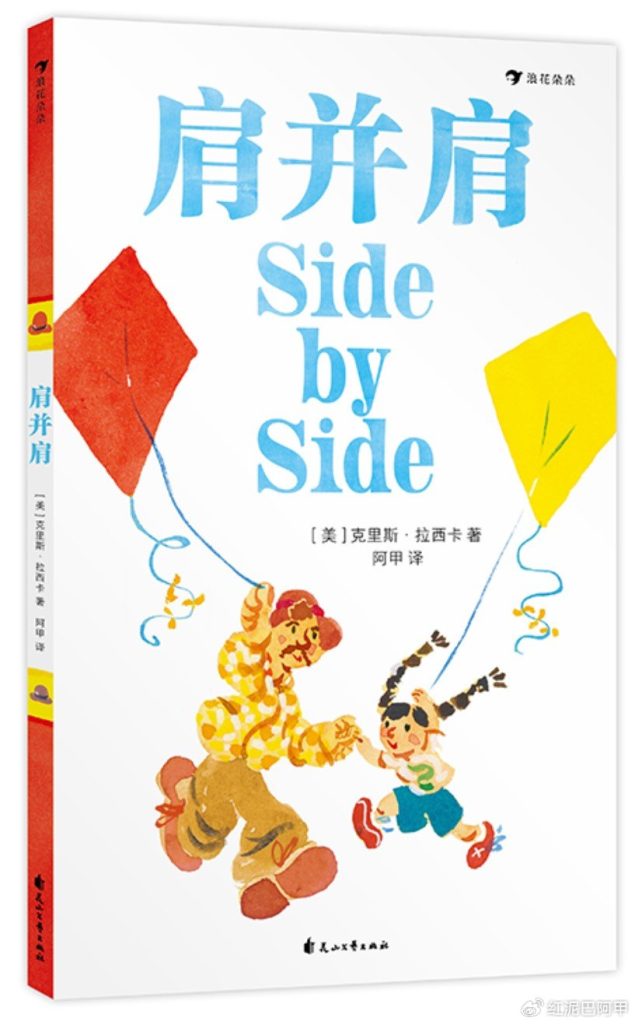

Shoulder to Shoulder has been labeled in the English-language world as a book particularly suitable for children aged 3–5. It is a refreshing and joyful breath of fresh air in the world of parent-child picture books, celebrating the bond between fathers and children. In the book, fathers are not just guardians of the family or playmates; they are also companions with whom children learn and grow, creating an irreplaceable bond. Rasika, with his distinctive style, captures this core concept, transforming it into a tangible and sensible work of art.

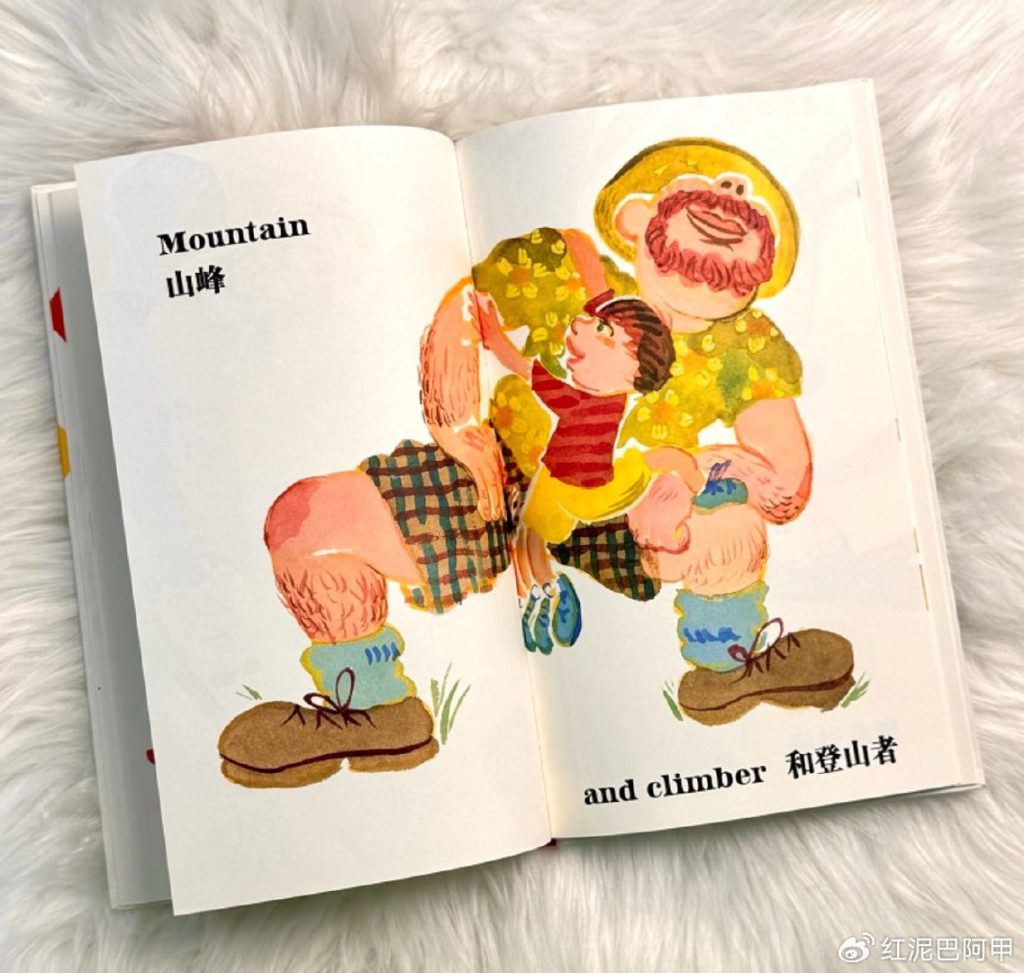

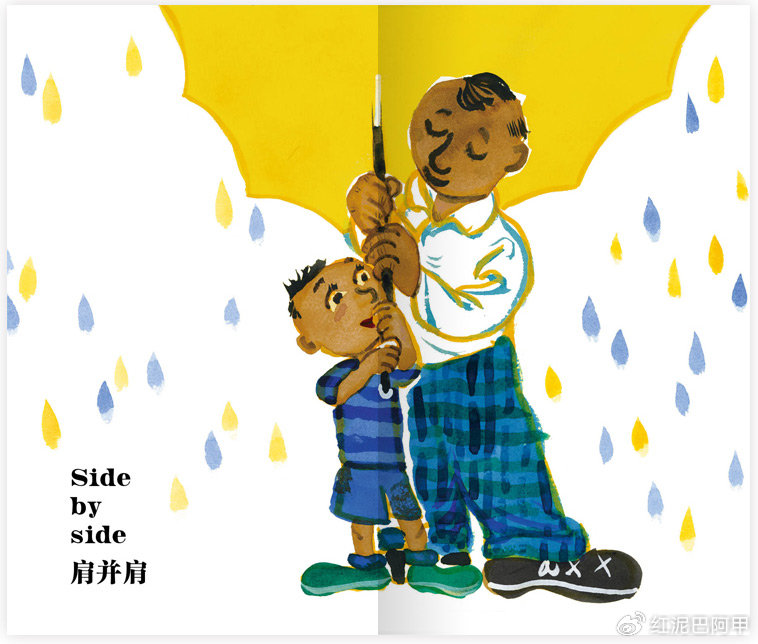

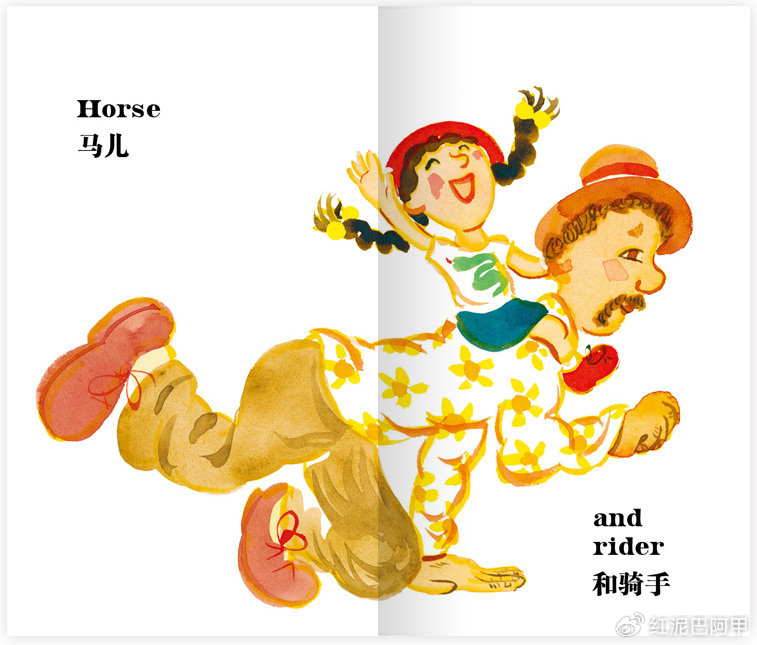

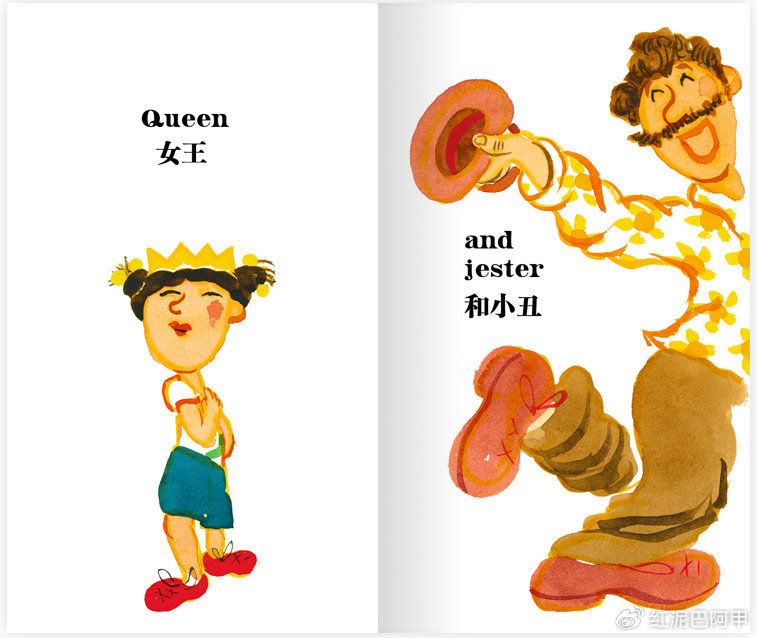

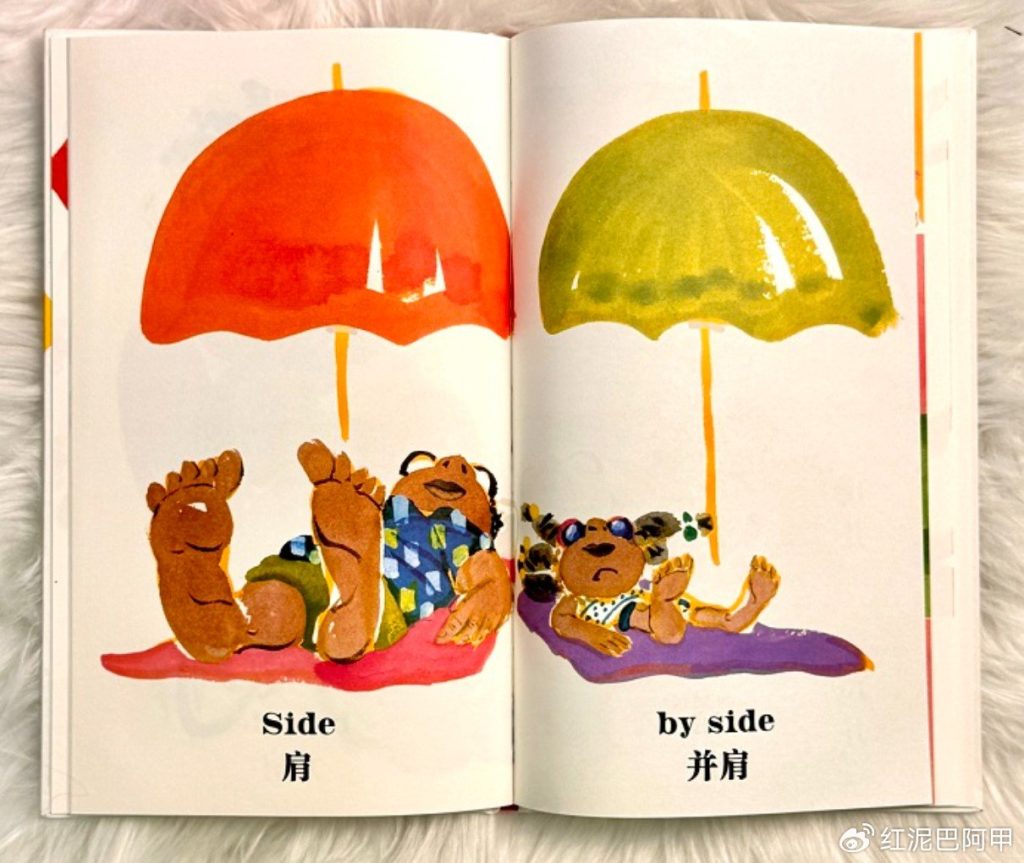

In this book, Rasika transforms his bold use of color and form into a visual poetry. The interactions between father and children in various settings are masterfully captured, from playful encounters at home to outdoor adventures. Every gesture and expression reveals a deep bond and unspoken understanding. Rasika’s vibrant colors and flowing lines easily capture children’s attention and spark their imagination. For example, the opening scene depicts the father and daughter, first as “horse and rider” and then as “queen and clown.” The entire scene is filled with childlike playfulness and the joy of parent-child interaction, creating a particularly warm and joyful atmosphere. The child’s exaggerated pretend play and exaggerated expressions, complemented by the father’s comical expressions and whimsical movements, both complement and contrast. The next scene, where the two enjoy kite-flying side by side, culminates in a joyful moment that strengthens the playful spirit, creativity, and family bonds.

Isn’t this scene suitable for parents and children to watch and reminisce together?

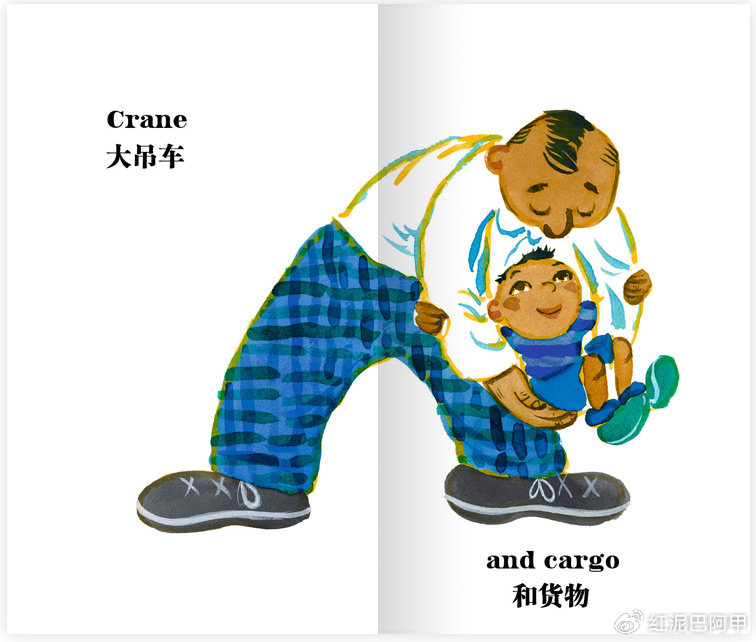

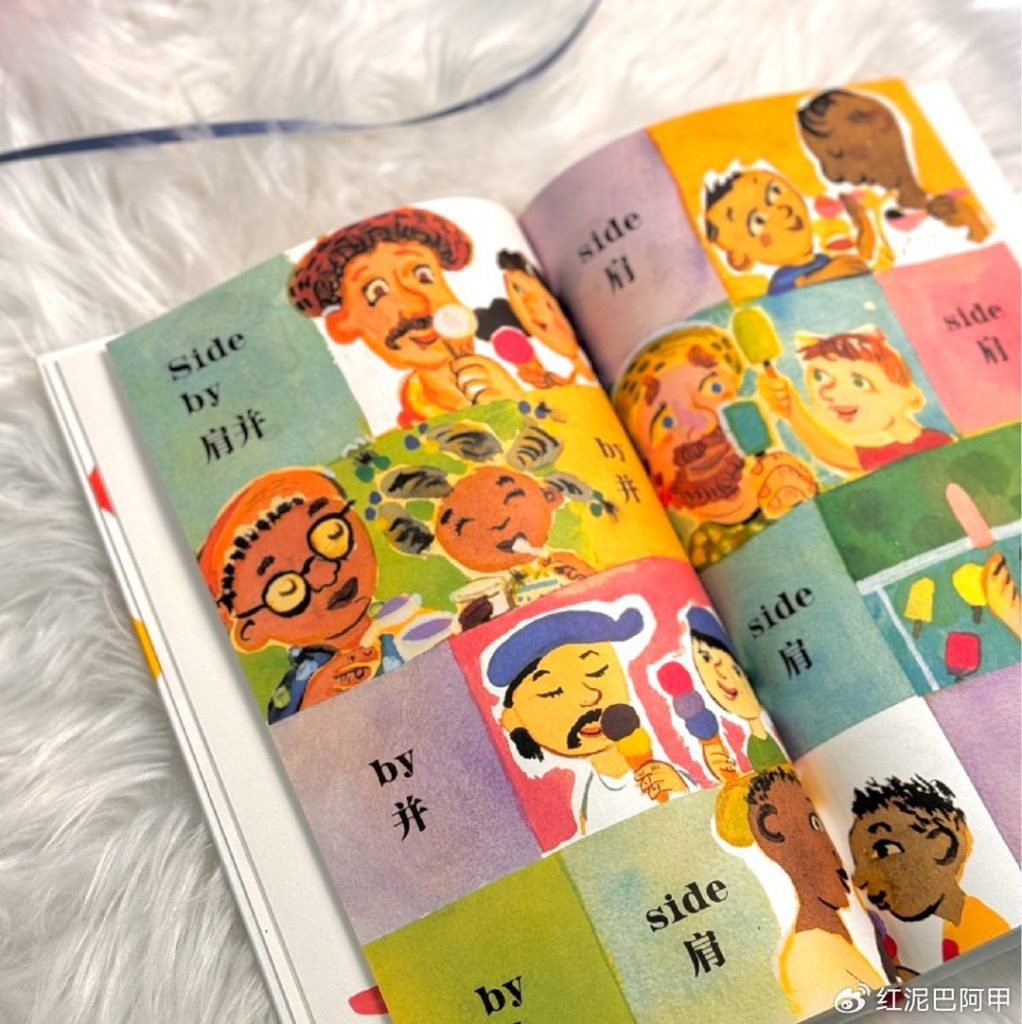

The book’s exceptionally concise text also imbues it with a special power. Lasica uses minimal words to narrate the story, a fact that allows for greater reader engagement. Coupled with the cheerful, lively, and evocative images, readers can connect with their own stories. The restrained nature of the text compels readers to engage with the images, filling in the unspoken details. “Large crane and cargo / locomotive and carriages / shoulder to shoulder”—these phrases, like rhythmic notes, blend seamlessly with the illustrations, forming a harmonious parent-child symphony. Accompanied by this light and dynamic melody, readers delightfully journey through stories that require no further explanation.

One particularly inspiring scene in the book depicts a father and daughter reversing roles: first, the father teaches his daughter how to fish, then the daughter teaches him how to jump rope. This isn’t just a playful setting; it also champions modern parenting. A father can be a humble learner, while a child can be a transmitter of wisdom. This reversal of roles captures the essence of education: mutual learning and shared growth. The original English phrase, “teacher and learner,” could have been translated as “teacher and student,” but these terms easily evoke the somewhat rigid roles of school. Therefore, I prefer the more colloquial term, “teachers and learners,” as these roles are inherently fluid and constantly shifting in real life.

When this book was published, Rasica filmed a short video explaining the inspiration behind it. It stemmed from a visit to his son Ingo’s art school in California. There, he and his son sat side by side, creating artwork together. He had methods to teach him, and he, in turn, had techniques to share with him. At the time, he couldn’t help but reflect on this father-son relationship, realizing that there were things his son knew that he didn’t, and things he knew that his son didn’t. This shared learning process was always a process of mutual exchange. Rasica felt this relationship was particularly worth celebrating, so he returned and created the book, Shoulder to Shoulder.

As a father of a daughter, I’ve had similar insights myself. Back in May 2004, I gave a lecture at the National Library titled “Picture Books and Parent-Child Reading.” One of the topics was “Picture Books: Children as Adults’ Teachers.” My daughter was less than five years old at the time, and I’d been exposed to picture books for less than three years. But much of my understanding of picture books back then benefited from my daughter’s help, especially regarding visual narratives and the relationship between text and images. She provided me with many insights. Therefore, I suggested at the time that if adults want to gain a deeper understanding of picture books, they should read more with their children, “seeing picture books through a child’s eyes.” Indeed, I still hold this view to this day.

In traditional Chinese family relationships and roles, fathers are often assigned the role of protecting and guiding their children. People often use the expression “fatherly love is like a mountain” to emphasize its depth and grandeur. But think carefully, isn’t this a sufficient reflection of the father-child relationship? What about the aspect of equal interaction, mutual learning, and shared growth? What about the humorous, playful side? Why not “fatherly love is like water,” encouraging, nourishing, and adapting? Why not “fatherly love is like light” or “fatherly love is like wind,” emphasizing the aspect of illuminating, blowing, and pushing? Why not “fatherly love is like a song,” metaphorically referring to the aspect that brings joy and encouragement, and may even inspire artistic inspiration? In modern society, the role of the father is quite diverse. Every father may have his or her own unique characteristics, allowing him or her to bring out his or her best strengths in the parent-child relationship.

In “Shoulder to Shoulder,” we see such diverse fatherly love. In fact, we also see fatherly love in multiple cultures and backgrounds. Those heartwarming pictures transcend cultural boundaries, showing fathers and children of all colors and nationalities, highlighting the universality and diverse beauty of family love. In those fathers who listen to, understand, and adapt to their children’s needs, we see “fatherly love like water”; in those fathers who exchange the roles of teaching and learning with their children, and play the roles of “dreamer” and “doer,” we see “fatherly love like light”; in those fathers who play games with their children and encourage them to climb and explore, we should also see “fatherly love like a song”… Therefore, such a picture book can indeed be said to be a “celebration of fatherly love,” and it is a celebration full of children’s fun and artistic interest.

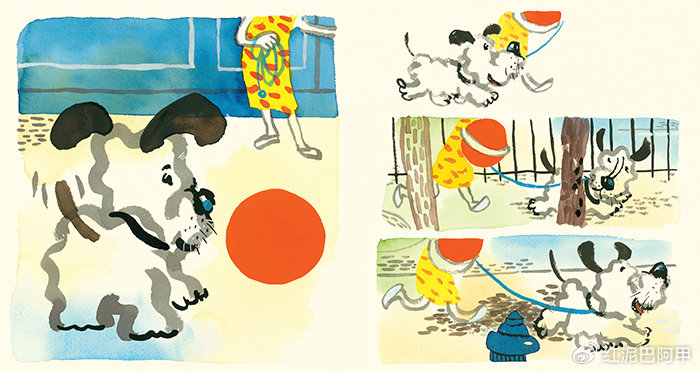

I can’t help but want to discuss a few more details about artist Chris Lasica, born in 1959. I met him closely in 2015 at the USBBY (US IBBY) conference. He’s a rather low-key artist. That year, he had already been nominated for the Hans Christian Andersen Award by the International Board on Books for Young People (USA) for the second time, yet he remained remarkably humble in his discussions and discussions. He primarily paints in watercolor, but his style has a strong influence on Chinese ink painting. He also enjoys classical Chinese paintings and has a particular fondness for Chinese brush calligraphy, but he doesn’t deliberately imitate Chinese painting techniques. He’s most drawn to the immediacy of painting, the seemingly uncertain yet expressive technique that reveals the artist’s emotions and personality in a fleeting stroke. He describes his greatest admiration as the “timeless immediacy” of the brushstrokes in ancient Chinese painting and calligraphy.

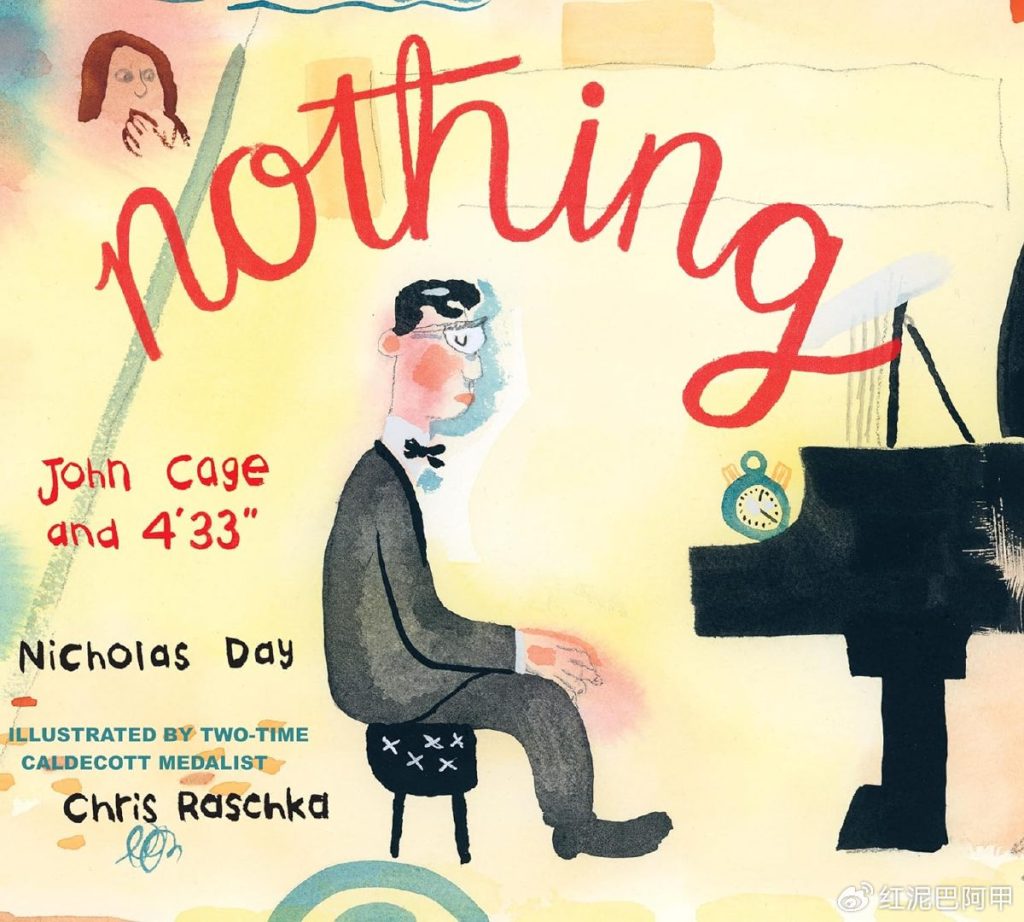

To appreciate Lasica’s illustrations, it’s important to understand his other identity: a skilled violinist. He’s been passionate about painting and music since childhood, developing and refining his hobbies. He majored in biology in college and, after some experience in the real world, was admitted to medical school. He had originally planned to become a doctor, but when he arrived at the medical school and was about to apply, he hesitated. After a sleepless night of brooding, he finally decided to give up the next day, fearing that medical school would mean he wouldn’t be able to continue painting. He chose painting as his primary career, forcing music to take a back seat. Whenever he had the chance, he explored the power of music through painting and picture books. For example, he created several picture books for children that explore jazz music and the lives of jazz masters. I suspect that for him, jazz, like traditional Chinese painting and calligraphy, holds a certain kind of immediacy. In 2024, he also collaborated with Nicholas Day to create the picture book “Nothing: John Cage and 4’33”, which tells a musical legend and is actually a discussion with children about what music is.

The immediacy and musicality of his painting style may be the most enduring stylistic feature of Lasika’s works. However, this style is highly changeable and fluid. The themes that Lasika is interested in are also very diverse, and any interesting bit of life can become his creative material. Therefore, it is difficult for readers to grasp his so-called “iconic” style.

Rasica has his own “system” for creating picture books. He places great emphasis on the integrity of his works. Although his paintings often appear simple and his brushwork somewhat casual, their overall structure is remarkably rational and rigorous. This may be due to his half-Austrian ancestry (from his mother). He always starts by making a complete “dummy book.” Once the overall structure is determined, he repeatedly creates “dummy books” of the same size as the finished book. Only when he is satisfied with the overall logic and the effect of the page turns will he begin to draw these seemingly random drafts. For example, the narrative of “Shoulder to Shoulder” is actually composed of a set of roughly three facing pages, alternating between father and daughter and father and son. There is a summary and transitional page between the first three sets. Doesn’t this resemble the creation of a short musical? Rasica also deliberately made the open facing pages a calm, full square shape, so that the closed book becomes a long, thin shape. This appearance makes this book quite unique in the picture book world, perhaps more likely to attract readers’ attention and make it a perfect gift!

When creating picture books, Lasica places particular emphasis on tactile sensations and the effect of turning pages. His approach is much like that of a craft designer, who prioritizes the user’s touch and experience. Furthermore, Lasica deliberately avoids pursuing the potential for “depth” in his images. He himself enjoys reading, both novels and text books, and believes that “depth” is essential. However, he believes that picture book illustrations don’t need to be excessively “deep.” They must reach the reader directly, leaving a strong impression through immediate experience. Therefore, when viewing Lasica’s illustrations, it’s helpful to completely relax and, like a child, simply let the images “come” to you.

To learn more about Chris Lasica, I highly recommend reading the lengthy conversation between Mr. Marcus and Lasica in the interview collection, “Why Picture Books Matter.” Lasica’s own upbringing, artistic pursuits, and family life have profoundly influenced his work. Just like this book, “Shoulder to Shoulder,” which Lasica dedicates to both his father and his son, he re-examines the role of father through this book. This kind of reflection and celebration can also be shared by every reader.

Argentine Primera División written on April 14, 2024 in Beijing