Recent readings of classical Chinese poetry have deeply resonated with Professor Ye Jiaying’s observations: if one fails to recite classical poetry according to its original level and oblique tones, half of its beauty is lost. However, the greatest difficulty with such recitation is that Mandarin lacks the entering tone found in classical Chinese. Therefore, she recommends that when encountering entering tone characters, one should try to pronounce them as oblique tones. The pronunciation of entering tone characters is short and concise, so listening to Professor Ye Jiaying’s actual reading of entering tone characters often reveals a close resemblance to the fourth tone of Mandarin, but with a short, rapid, and abrupt ending. [Reference video material:Ye Jiaying on the Tone of Reciting Classical Poetry]

But even if you understand the pronunciation principles above, another problem arises: how do you know which characters in ancient Chinese pronounce the entering tone? Of course, the most direct method is to look up rhyme books, such as Guangyun, Pingshuiyun, or Peiwenshiyun… find the entering tone characters, and memorize them! — Oh my god, what a dreadful and boring task! I’m sure few people could persevere through it, especially since reciting poetry is such a fun activity. Where’s the fun in that?

I would like to recommend a relatively easy method: just read the ancient poems one by one, pay attention to sorting out the entering tone characters in them, and slowly you will be able to recite them. Start with the most standardized regulated quatrains and regulated verses. With a preliminary understanding of the rules of level and oblique tones, you can find many suspicious entering tone characters. For example, when reading “野路径云皆黑,江船火独眠”, in order to comply with “仄仄平平仄,平平仄仄平”, all need to be level tones (after checking the ancient pronunciation, it turns out that they are read as ju1, the first tone, of course, this is not an entering tone character), while “黑” and “独” must be read as oblique tones (after checking, it turns out that both are entering tone characters). What tools should I use to check? I recommend two tools: “Wang Li Ancient Chinese Dictionary” andOnline Xinhua Dictionary (look up the word first and then look up the “Chinese Dictionary”)However, this method is also difficult for people with quick tempers, so I recommend the following sweeping method.

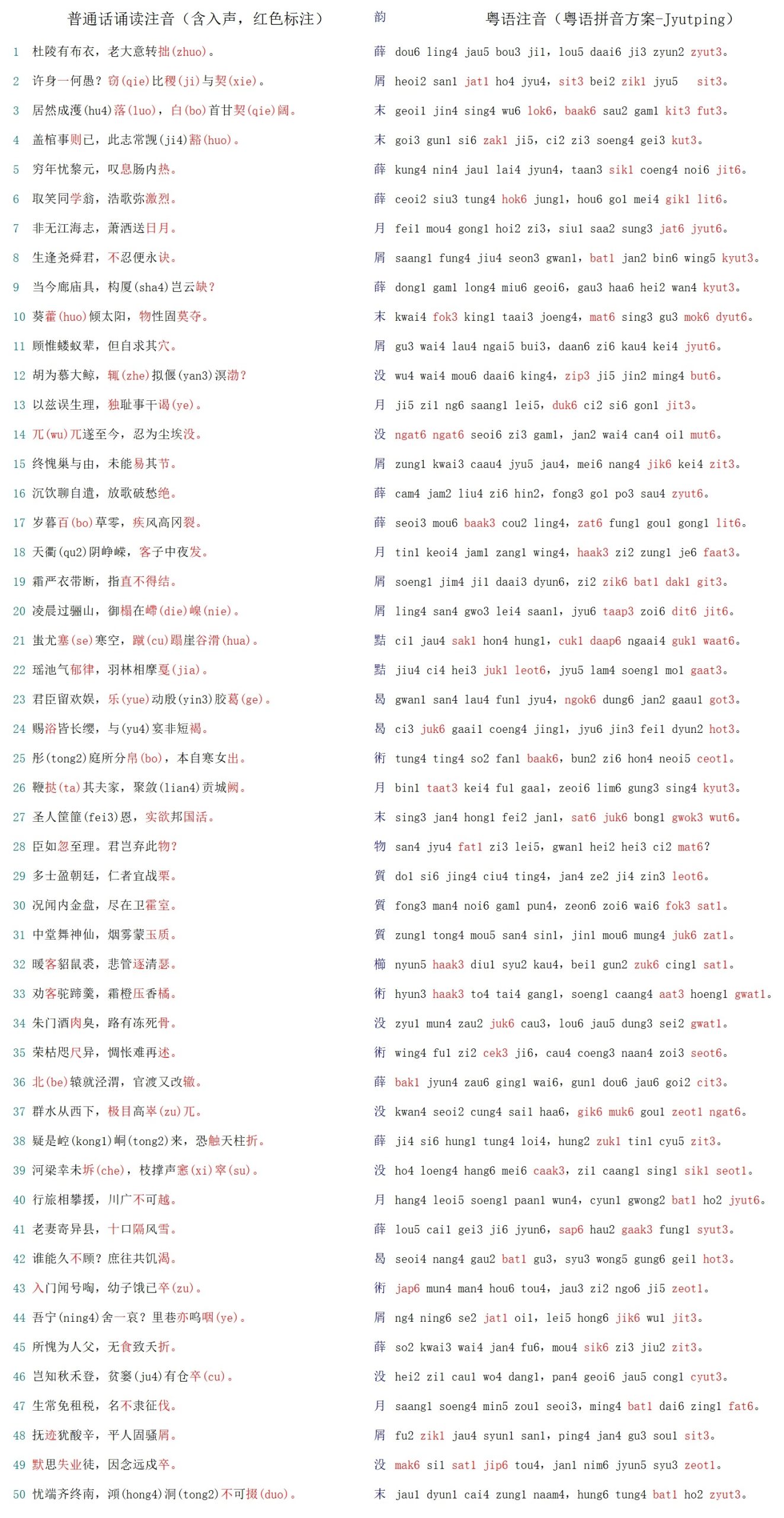

According to the “New Compilation of Poetry Rhymes,” Du Fu’s “Five Hundred Words of Poetry on the Way from Beijing to Fengxian County” and “Northern Expedition” have rhyme endings in entering tones that span all eight of our modern rhyme groups. A careful examination of the poems revealed that, in addition to the rhymes, these two poems contain a rich variety of entering tones, including most commonly used ones. So, if we can familiarize ourselves with these two long poems according to their original level and oblique tones, wouldn’t we also be able to quickly master the art?

The poem “Five Hundred Words of Reflections on the Way from Beijing to Fengxian County” consists of 500 characters, 121 of which are entering tones, accounting for approximately 241 TP3T. Of these, 50 are level tones in Mandarin, meaning that when read aloud in Mandarin, the discrepancy between level and oblique tones reaches 101 TP3T. Even more serious is the fact that the rhyme in this poem is an entering tone. If a poem cannot even pronounce the rhyme correctly, the loss of rhythm is self-evident!

In the phonetic notation below, I’ve highlighted the entering tone characters in red. Some are annotated in parentheses. Entering tone characters don’t have tones in their pronunciation, as Mandarin doesn’t have them. You’ll have to figure it out yourself. They’re usually pronounced as the fourth tone with a short ending, but sometimes it doesn’t have to be. You can go with your gut feeling, but a short ending is essential. Why isn’t it always pronounced as the fourth tone? I primarily used the entering tone of Cantonese as a reference. The Cantonese entering tone is further subdivided into yin ru, zhong ru, and yang ru, and the endings also have subtle differences in whether they close or open the mouth. For example, yi (jat1) ends in yin ru and closes the mouth, bai (baak3) ends in zhong ru and closes the mouth, and ye (jip6) ends in yang ru and closes the mouth. Therefore, I suspect that even in ancient Chinese, not all entering tone characters resemble the current fourth tone.

For reciting ancient poetry, the Cantonese dialect is a great auxiliary tool. I don’t speak Cantonese very well, but with the help of reference books and online reference tools, and relying on the help of my Cantonese-speaking wife, I can basically use the Cantonese pronunciation for reference. At the same time, the Cantonese pronunciation of these 500 words is attached. The Cantonese pinyin scheme is mainly used in Hong Kong and abroad. It is different from the “Guangzhou dialect pinyin scheme” in the “Guangzhou phonetic dictionary” in phonetic symbols, but the pronunciation is generally the same. The reason for using the Hong Kong Cantonese pinyin scheme is that there are very convenient audio materials on the Internet. You can find the standard pronunciation based on this pinyin. Just remember this link:

http://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-can/sound.php?s=zyut3(The red text can be used to replace the Cantonese pinyin you want to look up)

Compare the pronunciation of Mandarin and Cantonese. For this poem alone, all the characters pronounced as entering tones in Cantonese also happen to be pronounced as entering tones in classical Chinese! (The Cantonese pronunciation pattern for entering tones is very clear: they all end in p, t, or k, with p closing the mouth, and t and k not closing the mouth.) I think this is why reciting classical poetry in Cantonese feels so natural.

In addition to entering-tone characters, I’ve also annotated some uncommon characters or polyphonic characters in Mandarin recitation. I’ve used a number after the tone to indicate the tone, such as “ji” (ji4), pronounced as “ji” (ji4). A polyphonic character in poetry is pronounced differently depending on its meaning, but sometimes the meaning can be interpreted differently, and it can be difficult to determine which is correct. Later, I’ll attempt to explain my understanding of some of these characters.

I’ll read it aloud first, using Zhuyin. My reading may not be accurate, so it’s just a rough guide, especially since the Cantonese part is more inconsistent. But I figured having a voice to guide me was better than going in the dark, so I’ll just go for it here, and make the experts laugh. Just show off your ugliness!

【Notes】

Extensive explanations and annotations have been made regarding the meaning of this poem (though some disagreement is welcome). Here, I’ll only provide the pronunciation for its recitation. Our predecessors (especially the ancients) rarely addressed this issue. The occasional annotations for “something” (likely a Chinese character for “something”), like “something” (likely a Chinese character for “something”), might not necessarily be clear to modern readers, as the “something” itself is pronounced in the ancient sense! The ancients largely omitted pronunciation, perhaps assuming that scholars would already know it. Or perhaps, given their long-standing habit and tradition of recitation, passed down from master to apprentice, there was no need for such effort.

However, even today’s scholars, even those pursuing postdoctoral degrees, may not have access to such courses. I carefully listened to the recordings of Professor Mo Lifeng’s “Study of Du Fu’s Poems” at Nanjing University and benefited greatly from it. It’s a very solid and profound course, and I regret not having such a good teacher in college. Even Professor Mo, who has delved deeply into Du Fu’s poetry, doesn’t pay much attention to how to read it aloud. At the very least, he completely dismisses entering-tone characters, as if this issue is unimportant. But how can you truly appreciate Du Fu’s “melancholy and stammering” without reciting them aloud?

Among the texts that helped me the most in explaining or annotating this poem, Ye Jiaying’s Commentary on Du Fu’s Poetry (Ye Jiaying), Mo Lifeng’s Lectures on Du Fu’s Poetry (Mo Lifeng), and Qiu Zhaoao’s Detailed Notes on Du Fu’s Poetry were the most helpful. Qiu Zhaoao’s notes are particularly noteworthy for their numerous phonetic notations, a rare find for an ancient annotated text. I also consulted the notes by Qian Qianyi and Zhu Heling, as well as the explanations and phonetic notations in Selected Poems of Du Fu (Ge Xiaoyin) and Selected Poems of Du Fu (Zhang Zhonggang). Below, I share some of my notes on pronunciation for your critique:

2

(The second line, the same below, omitted.) “Qie” is pronounced (xie) here (entering tone), and Qiu’s pronunciation is “xie,” which is also an entering tone. Here, along with “ji,” it refers to the names of two virtuous ministers during the reign of Emperor Shun. There are two other pronunciations of “qie,” the most common being “qie” (qi4) as in “contract,” and the other being “qie” (entering tone) as in “qie kuo” (qie kuo) in the third line.

3

The ancient pronunciation of “濩” (濩) has two possible pronunciations: huo (entering tone) or hu4 (falling tone). It is now pronounced huo4 (falling tone). Both the Ge and Zhang versions listed above pronounce it as huo4 (falling tone). Zhang’s version notes, “濩落 (濩落) is a character with repeated rhymes and continuous flow, similar to the word 落拖 (落拖).” Ge’s version notes, “濩落 (濩落): large and without proper meaning.” The latter meaning comes from the Zhuangzi passage “瓠落沒存 (瓠落 wu hu wo rong).” Ye Jiaying and Mo Lifeng also interpret it in this way, as do Qiu and Zhu’s annotations. Therefore, I tend to believe that “濩落” (濩落) means “瓠落 (瓠落).” In this case, “濩” (濩) should follow “瓠” (瓠落) and be pronounced as hu4 (falling tone), not hu4 (falling tone). Even if it were to be pronounced as huo, it should be pronounced as an entering tone, not a falling tone, because the following “落” (落) is also pronounced as an entering tone, thus creating a continuous rhyme.

20

I didn’t specifically annotate the pronunciation of the character “过” (guo) in this line because I wasn’t sure. In “Making Friends with Ancient Poetry,” Professor Ye Jiaying emphasized that if the character “过” (guo) in ancient poetry is a verb, it should be pronounced as “ping” (guo), as in “youyuebulaiguoyeban.” However, I’ve searched the available resources and found no evidence to support this claim. Furthermore, in the recording from the same book, Professor Ye also pronounced “过” (guo) in “qingzhouyiguowanchongshan” (qingzhouyiguowanchongshan) as “qu” (guo). So, for now, this question remains unanswered.

The word “嵽嵲” in this line is a rare word. Its ancient pronunciation had two entering tones, and it is now pronounced “叠娘.” Qiu’s annotations say it means “mountain high appearance.” Ye Jiaying says the word choice here is clever, as the two characters look ugly and the stroke combination is terrifying, subtly suggesting that the emperor’s hiding in Mount Li at this time is not a good thing. This interpretation is very interesting.

21

“塞” (塞) is pronounced (se) in the entering tone. Qiu’s note: “先则切” (先则切) is a common character, but few have explained it. Here, it should mean “filling the air with fog,” but the ancient pronunciation is pronounced in the entering tone, meaning that the cold sky is filled with fog. Chiyou is a synonym for fog. Incidentally, Qian’s note says that “Chiyou is used to metaphorically represent military events” because the poem was written in early November of the 14th year of the Tianbao reign (755), the same month An Lushan launched his rebellion. Professor Mo Lifeng believes that Qian’s note is “too far-fetched” here. Although An Lushan had already begun his rebellion, the news had not yet spread, and Emperor Xuanzong of Tang did not believe it; otherwise, he would not have been so carefree as to remain at Mount Li. Therefore, Du Fu did not know this, let alone “a metaphor for military events.” I believe Qian’s commentary lacks the opportunity to expand on this point. While its logic may seem flawed at first glance, a closer look at the political situation at the time reveals that the person most slow to react to news of the rebellion was the already incompetent Emperor Xuanzong. Rumors of An Lushan’s rebellion predated the rebellion, some likely fabricated by Yang Guozhong to pressure him into rebellion. Du Fu likely heard these rumors and harbored concerns about the stability of the Celestial Empire. The lines “The thoroughfares of heaven are gloomy and rugged,” “Chiyou blocks the cold sky,” “fear of breaking the pillars of heaven,” and “the rustling of supporting branches” have all fueled this line of speculation. Therefore, I believe Qian’s commentary is quite insightful on this point.

23

Yin, pronounced (yin3, rising tone), Qiu’s note: the sound is yin. Professor Ye Jiaying explained that the “Book of Songs” contains a poem called “Yin Qi Lei,” where “Yin” means loud. Professor Mo Lifeng explained that this comes from Sima Xiangru’s “Shanglin Fu,” where the line “Yin moved the heaven and earth” is “Zhen.”

24

与, pronounced yu4 (falling tone), comes from Qiu’s annotation. It should mean: attend or participate.

26

The character 領 (lian4) is pronounced in the falling tone, and comes from Qiu Zhu. The character 領 (lian4) in “gathering” (accumulating) is pronounced in the third tone in Mandarin. In ancient Chinese, it was pronounced in both the rising and falling tones, but the falling tone seems to have a different meaning, such as the character 殓 in “burial” (commonly used for burial). Why is Qiu Zhu’s note using the falling tone here? I don’t understand it yet, so I’ll leave it as a question.

33

I can’t help but wonder, the “ju” in “Frosted oranges press fragrant oranges” and the “gu” in “Road to frozen bones” are pronounced exactly the same in Cantonese! Is it just a coincidence?

44

Ning (ning4, falling tone), how can, how can, how can; rather. Ms. Ye Jiaying explains that “Wu Ning She Yi Ai” can be interpreted in two ways: How can I let go of my own sorrow (because my young son died)? I would rather let go of my own sorrow (because so many people in the alleys and lanes also starved to death).

46

Cangzu, the same as “Cangchu”, “zu” is pronounced as “chu”. Ju4 means poor.

50 澒洞, Mandarin read (hong4

tong2), Cantonese reading (hung6

tung4), and reference books have dedicated entries for it. Zhang Zhonggang’s annotation: “continuous,” “diffuse.” Ye Jiaying’s explanation: “boundless, expansive.” Mo Lifeng’s explanation: “vast and boundless.” Qiu’s annotation quotes the Huainanzi: “Before heaven and earth existed, primordial chaos existed.” Qian’s annotation quotes Xu Shen’s Huainanzi: “澒” is pronounced as “Xiang” in Xiang Yu; “洞” is pronounced as “Tong” in Tong You. Even a great scholar like Qian Qianyi would have kept his annotations extremely simple, and phonetic notation was even rarer. Wouldn’t the pronunciation here be difficult for him to read? Interestingly, the ancient pronunciation of “Xiang” is also pronounced as “hong4” in Mandarin and “hung6” in Cantonese.

掇, pronounced as (duo1) in Mandarin, means to pick up, sort out, or put away. Its ancient pronunciation is the entering tone.

The Argentine Primera División came to an end on the night of January 2, 2011

[Attached are some beginner’s experiences]

[Notes] My thoughts on reciting ancient poetry for beginners

Chatting with my children about “Seven-Character Verse: The Long March”