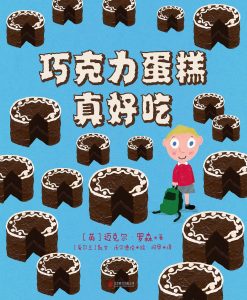

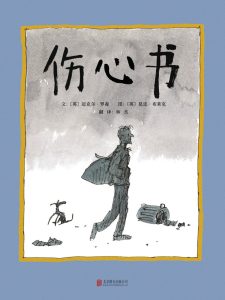

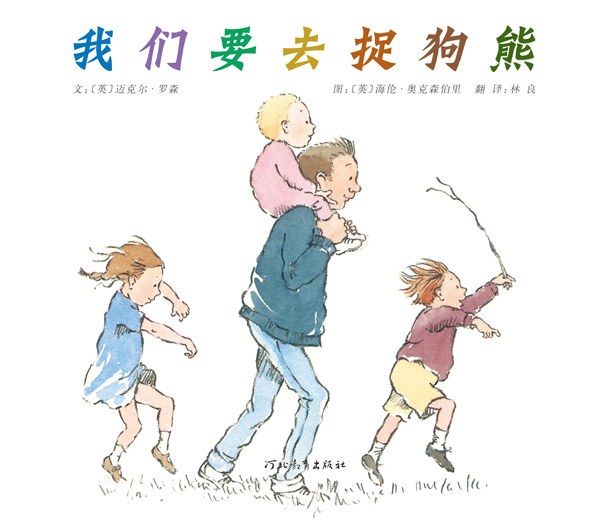

Michael Rosen (1946~), the British laureate children’s book author, may be a familiar yet unfamiliar figure to Chinese readers. He became a sensation on the Chinese internet for his expressive “Nice” emoji, but few Chinese readers have fallen in love with this “Nice Grandpa” because of his works, and even fewer know his life story. He has written more than 200 books for children and adults throughout his life, and more than a dozen have been translated and introduced to China. Among the most famous are the picture books *We’re Going on a Bear Hunt* (illustrated by Helen Oxenbury), *Sad Book* (illustrated by Quentin Black), and *Chocolate Cake* (illustrated by Kevin Waldron)—I was fortunate enough to translate the latter.

If you’ve read his picture books, you’ll agree that “Grandpa Nice” is first and foremost a poet, exceptionally skilled at writing rhythmic verses; moreover, he’s a rather humorous poet, as even his poems depicting everyday life always manage to elicit laughter. Furthermore, he’s a seasoned actor, his own nuanced performances often resembling a captivating one-act play. In fact, the “Nice emoji” originated from a video of him telling a story. However, *Sad Book* is a rare exception. That book stemmed from his immense grief over the loss of his son, and he found comfort and healing through sharing that experience. During the 2020 pandemic, after contracting COVID-19 and spending 48 days in intensive care, he miraculously survived. He even wrote a biographical collection of prose poems, *Many Different Kinds of Love: A Story of Life, Death and the NHS*, reflecting on that experience, expressing gratitude for life, and especially thanking the healthcare workers who saved his life.

“Grandpa Nice” is essentially a master storyteller who uses humorous and rhythmic language to tell stories rooted in real life and genuine feelings. Sometimes his stories are very realistic, and sometimes they are full of fantasy, but at their core they are very sincere. If you savor them carefully, you’ll find something substantial—delicate emotions, deep love, and profound wisdom about life. In short, like a richly flavored chocolate cake, it has a unique and layered flavor that is irresistible and leaves a lasting impression.

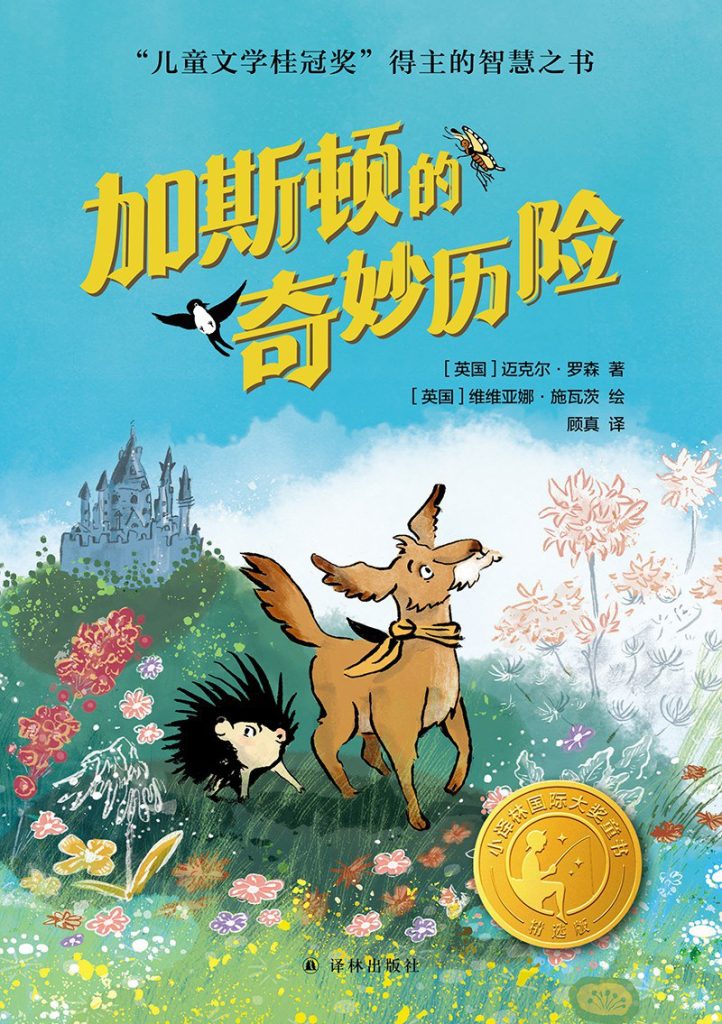

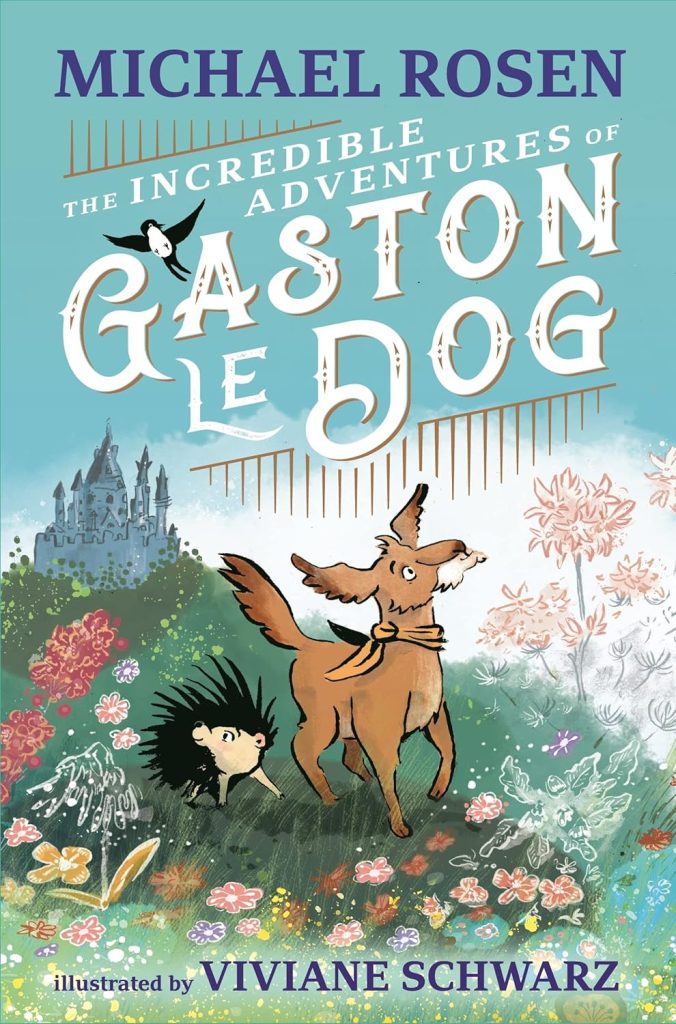

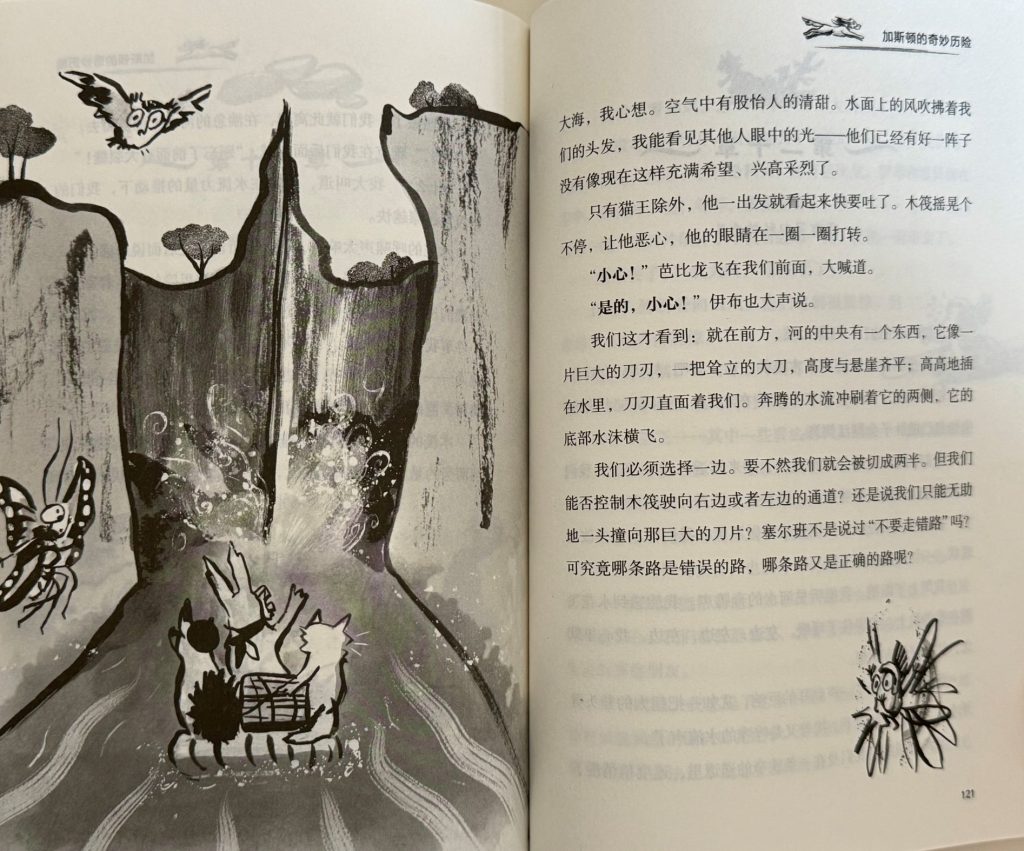

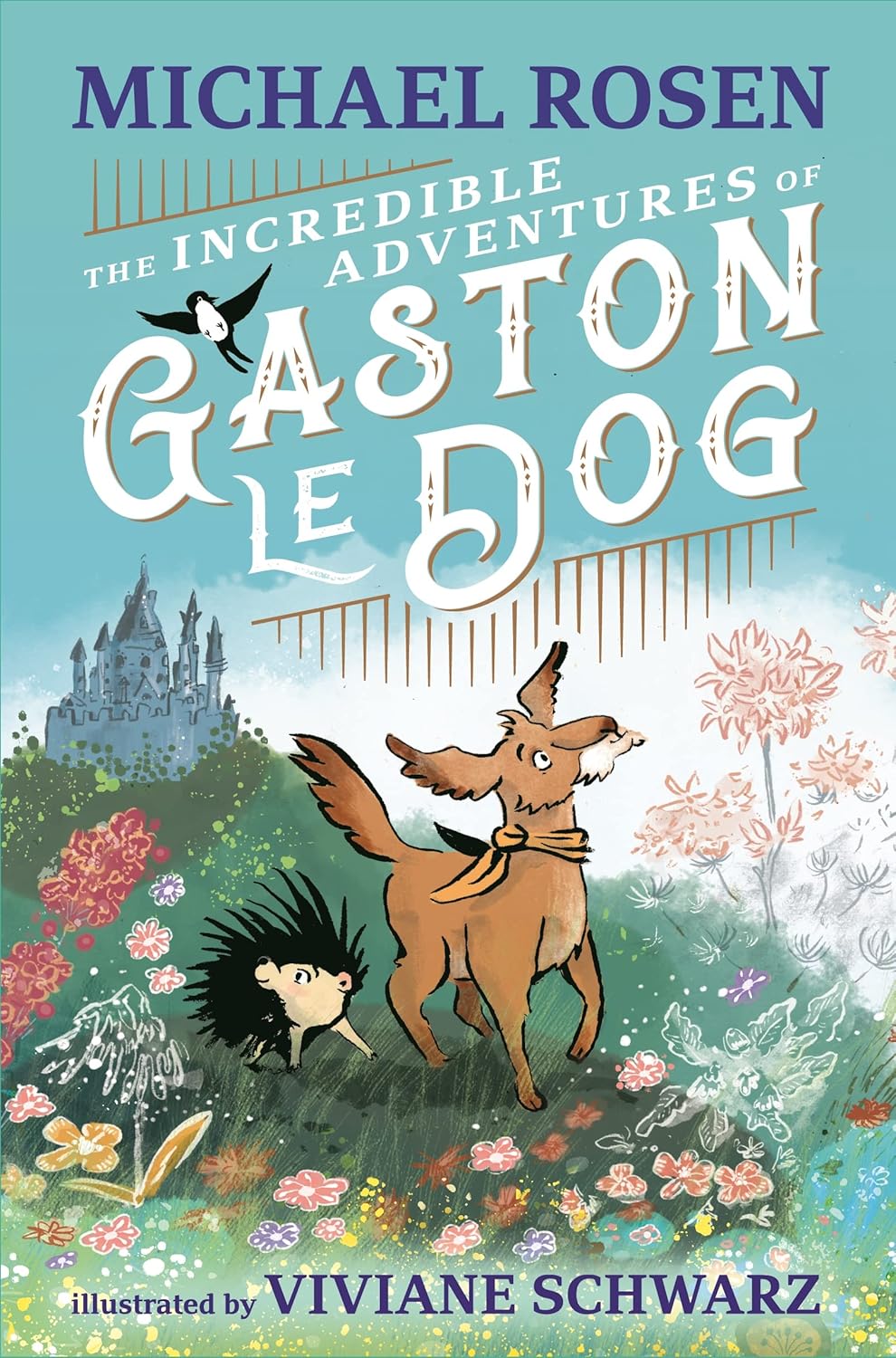

Okay, let’s get down to business and talk about his 2023 children’s novel, *The Incredible Adventures of Gaston the Dog*. It’s said that this was a work he vowed to complete after his near-death experience that year. Despite suffering from the aftereffects—irreversible damage to his eyesight, hearing, and memory—the adventures of “Gaston the Dog” became one of his greatest creative desires, almost as a form of self-healing. Completing this story felt like embarking on a new adventure, another “hero’s journey.”

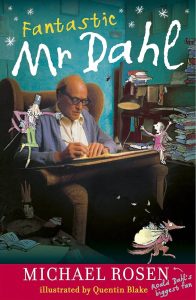

Coincidentally, before reading this book, I had just finished translating Rosen’s *Fantastic Mr. Dahl*, written for young readers. That book, rather than being a biography of the famous children’s author Roald Dahl’s upbringing, was more like a treasure trove of “writing secrets” from Rosen, a master storyteller himself, introducing Dahl as a master storyteller. That book focused more on analyzing the connection between Dahl’s development and his superb writing skills. Inspired by this, I also wanted to try a similar approach to tell the story both inside and outside this adventure children’s book.

First, this fairy tale has a strong “oral story” feel. Judging from the dedication, the father, Rosen, dedicated the book to “Emile,” because when Emil was young, he would constantly ask Rosen to tell him another “Gaston’s Story” during the long summer days. According to a 2021 report in the British newspaper *The Guardian*, Emile was Rosen’s youngest son, around 16 years old at the time. In short, Rosen has been married three times, has five biological children, and two stepchildren. His late second son, Eddie, is the protagonist of his *Sad Book*. “Gaston’s Story” is a story specifically for his youngest son, Emile—“Your dad, who loves you so much,” wanted to finish telling this story after miraculously surviving intensive care, suggesting that the story contains some important information.

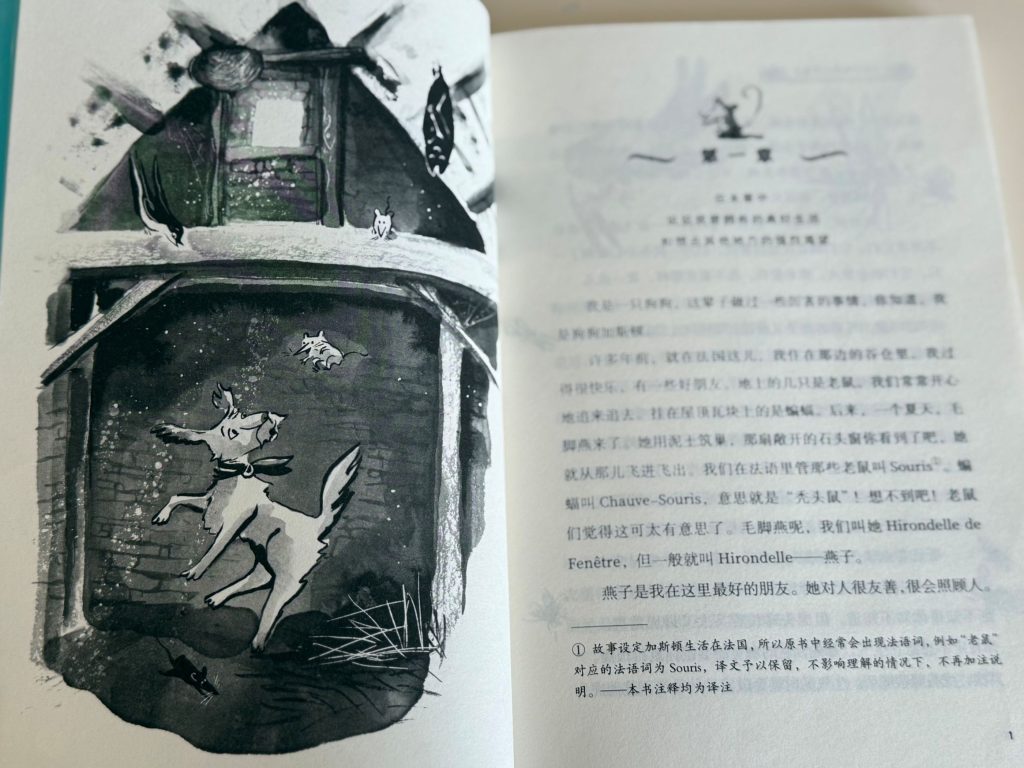

As an oral story, it inevitably has an “improvisational” element. For example, this story was told by Rosen during his son’s vacation in France, so the story is set in France; the names of the animal characters are also convenient, they are their French words (the Chinese translation is a transliteration): the dog is “Gaston,” the hedgehog is “Hérisson” the butterfly is “Papillon,” and the fox is “Renard”… The development of the plot also seems somewhat arbitrary, with a general direction—“Gaston the dog is going to the beach of his childhood,” and the story in between can be made up at will, whether it is near or far, long or short, new characters and new plots can be added at any time, and can be skipped at any time, as long as the listener is happy.

This kind of “oral storytelling” is incredibly beneficial for developing parent-child relationships, because it feels like a collaborative product between the speaker and the listener. A child’s interruptions and questions can change the direction of the story; a child’s strong interest in a particular character or plot can inspire the speaker to improvise even more enthusiastically. If both are in high spirits, they can continue the story; if they’re tired, they can stop for a while and continue tomorrow. No wonder little Emil keeps asking his father to tell him another one. It’s easy to imagine how much this father, over sixty years old, loves his young son; naming him after his childhood hero, “Emil” (the little detective in Erich Kästner’s *Emil und die Detektive*) speaks volumes. His storytelling and performance at this moment embodies a lifetime of experience creating poetry, drama, and fairy tales for children, coupled with a precise understanding of child psychology.

He chose to narrate from Gaston’s perspective, using the first-person narrative, which perfectly showcased his veteran acting talent. Gaston’s soliloquy and psychological development are presented very transparently as the plot unfolds. Borrowing from Rosen’s observation in *Fantastic Mr. Dahl*, “One interesting thing about reading these kinds of works is thinking about ‘who is really talking’ ”—on the surface, the whole story is told by Gaston, but in reality, it’s all Rosen’s words; Rosen is “real.” Gaston’s childlike expressions are interspersed with insights into growing up, and reflections on ethics and life wisdom at crucial moments. These are all spoken by Rosen, the “dad,” but delivered through Gaston’s mouth, they feel so interesting, so natural, and often invite young readers (listeners) to interact.

When young readers encounter such a story, they are likely to feel an irresistible urge to participate: The little hedgehog with short legs, who doesn’t seem to run very fast, also wants to go to the beach—should we take him along? The colorful butterfly that loves to flutter around—should we let her come along too? Faced with a high wall they can’t cross, should they try together to guess “the word” that can open the door?… Because it’s Gaston the dog telling the story, and children have clearly fallen in love with this humorous protagonist from the very beginning, they will all choose to “stand on Gaston’s side,” and thus, they will definitely participate. This, of course, is another secret to Rosen’s storytelling.

Just as Dahl always managed to ensure readers sided with his young protagonists (such as James, Charlie, George, Danny, Matilda, etc.), Rosen excels at it as well. Gaston the dog wins over young readers from the very beginning; he’s lively, intelligent, innocent, fearless, adventurous, and always ready to act (though perhaps a little reckless)—a perfect fit for children’s nature. However, Rosen’s brilliance lies in not making Gaston a “lofty hero” from the start. In fact, Gaston is initially clueless, with only vague memories of the beach and no idea how to get there. He even hesitates about the hedgehog and butterfly who want to join him. During the adventure to the beach, he’s not always the smartest or the most crucial; he’s helpless, succumbs to cravings, is misled by illusions, succumbs to the temptation of treasure, and disregards the prophetic advice of the wise snake Serpent… In short, he struggles to avoid all the flaws and mistakes of ordinary people. Interestingly, Gaston remains a very endearing character because he is incredibly sincere and straightforward, always correcting his mistakes; he always cares for his companions, even tolerating former enemies like the cat king; and he never abandons his initial dream of going to the beach, demonstrating unwavering commitment in this regard. Therefore, he ultimately becomes the leader of the adventure team and leads everyone to the real “treasure.” From this perspective, this adventure is precisely Gaston’s journey of growth.

Some overseas readers have commented that Gaston possesses a “Don Quixote-like” heroic quality upon his introduction, which is an interesting perspective. This is mainly because Gaston’s innocent and fearless journey to the beach for a wondrous adventure feels like a hero’s “long and adventurous voyage”—his English name “Odyssey” originates from the ancient Greek hero Odyssey’s journey home. Attentive readers might compare the similarities: Gaston is summoned to embark on a journey, constantly joined by friends (teammates), gets lost but receives necessary guidance, stumbles into the villain’s castle, receives advice from a prophet, falls into a magical predicament, escapes and enters a passage, is bewildered by various illusions (fossils and dream palaces) during his escape, and is tempted by human weaknesses, only to find upon arrival that it’s just the beginning of a new adventure… Doesn’t this perfectly contrast with and echo Odyssey’s heroic journey home?

In fact, such journeys can be associated with many others, such as Frodo’s “Fellowship of the Ring” in *The Lord of the Rings*, which is also well-known. Regarding this type of “heroic journey,” according to Joseph Campbell’s summary in *The Hero with a Thousand Faces*, it generally involves a process of “journey—turning point—return.” Comparing Gaston’s journey: the starting point—the call to action; stepping out of the ordinary—the path of trial; the crucial turning point; the escape from magic and the end of the journey; return and acceptance: a return and sublimation… it also conforms to the paradigm of a heroic journey, the difference being:Gaston’s adventure is not about a hero embarking on a journey, but about an ordinary person becoming a true hero after experiencing the journey.

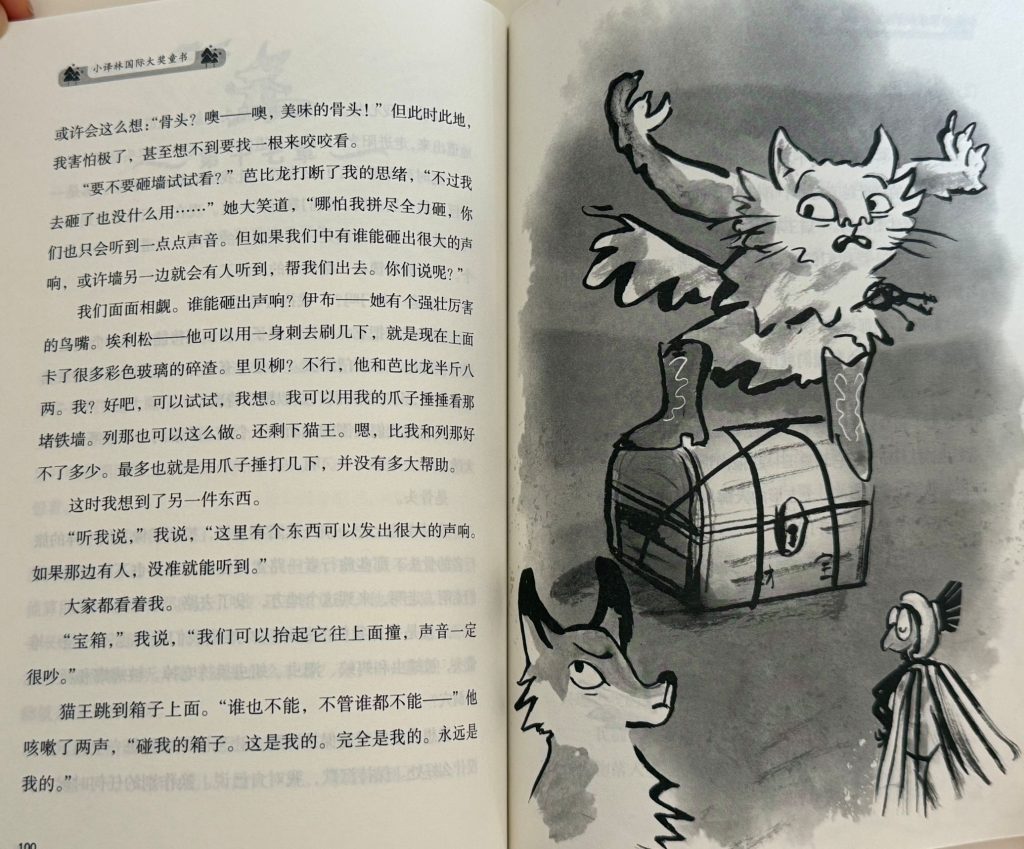

Therefore, although this is an “oral story” with a seemingly less rigorous narrative structure, Rosen, a master storyteller, strictly adheres to the traditions of classic human narratives, a meaningful tradition that can be traced back to the time of Homer’s epics. Of course, young readers don’t need to concern themselves with this classic literary paradigm; they can simply fall in love with the story because of certain familiar elements.Talking animals, treasure hunts, making friends, each displaying their unique abilities, working together to defeat opponents, magic, transformation, castles, traps, mazes, puzzles, finding an exit, escaping, gaining freedom, and more.The most thrilling and exciting part of the adventure incorporates the classic fairy tale “Puss in Boots,” which they are particularly familiar with. The “cat king” in the book is actually the legendary cat from the world of fairy tales, but in this newly adapted story, he plays a less-than-honorable role.

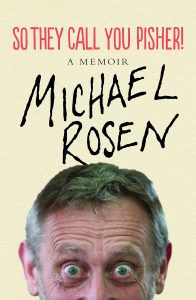

In his autobiography, *So They Call You Pisher!: A Memoir*, Rosen recounts how, at the age of seven, he submitted a writing contest to *The Daily Worker*, winning an award and receiving the honor of publication. His piece was essentially a retelling of a story he had read, “Solomon the Cat,” at a time when he couldn’t distinguish between “original” and “parody.” His parents, both radical communists from East London with strong internationalist ideals and numerous opportunities to connect with transnational workers’ communities, frequently read children’s books from around the world to him and his brother—a practice he later realized was quite avant-garde for its time. In short, he grew up immersed in stories, developing a lifelong passion for language and literature, which likely contributed to his decision to abandon medicine for literature at university.

In other words, Rosen telling stories to his youngest son was a natural continuation of the family tradition. Since they were telling stories during a vacation in France, he decided to pick one that had a strong French flavor: *Puss in Boots*. This fairy tale has different versions throughout Europe; the earliest written version was in Italian, but the most widely circulated is the version included in *Mother Goose Tales* (Les Contes de ma mère l’Oye) by the French writer Charles Perrault. Of course, Rosen wouldn’t simply imitate it as he did when he was seven. He cleverly borrowed this well-known fairy tale, seemingly continuing it, but actually subverting the entire story. The original story was full of cleverness, but the cat’s “cleverness” was actually a series of lies that fooled the king, defeated the ogre, gained wealth and status out of thin air, and rearranged the fates of the miller’s youngest son and the princess. So, did they “live happily ever after”?

I suspect that Emil must have heard the story of Puss in Boots before telling Gaston’s tale. So, when the wise snake Serpent tells Gaston and the others the origin of “cat king,” the butterfly Barbie Dragon can’t help but interject, immediately pointing to the source of the original fairy tale—this is probably equivalent to young Emile’s interjection. Through this “intertextuality,” the reader is immediately drawn into the story, and then, through Serpent’s abrupt and dramatic follow-up narration, the story becomes, as Papillon laments, “…now a horror story. A terrible and annoying trap!” But why is this?

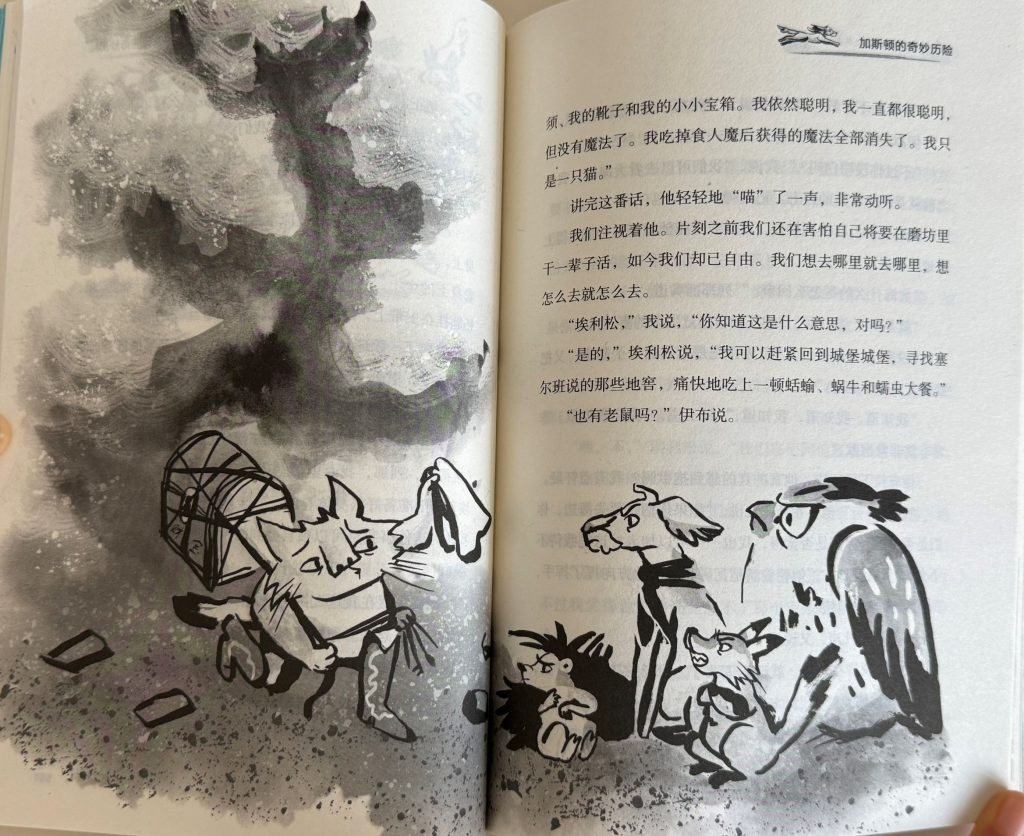

Selban’s explanation is that,The cat that ate the ogre also gained the ogre’s magical abilities, and the cat gradually became more and more like the ogre!This is a very interesting metaphor, revealing Rosen’s insight into the darker side of human nature. The increasingly evil Elvis becomes someone everyone avoids, even his former master and princess are not spared. Growing increasingly lonely, he can only turn passersby into “goblins,” enslaving them to maintain the castle’s operation. The magical element that turns these passersby into “goblins” is their inability to resist the temptation of enchanted “food”! Interestingly, Gaston and Elison, knowing the evil consequences, also succumb to temptation, while only Barbie Dragon passes the magical trial. Why? Is it because she is most familiar with the story of “Puss in Boots”? It seems that reading (and listening to stories) has its benefits!

The hero of classic fairy tales has become the evil cat king in a new story, and the mechanism of his transformation may be related to the treasure chest he has always been obsessed with guarding. It was originally the treasure of an ogre, and may have initially been obtained through plunder. This so-called “treasure chest” is much like the One Ring that Frodo was about to destroy; it possesses a powerful “corrosive force.” Whoever gets attached to it becomes filled with greed, and the closer and longer they are, the greater the corrosive effect. Even Gaston couldn’t resist tricking himself by hiding a silver chain when trying to pass through the obstacle. Ultimately, only by completely letting go can one pass through, and the true “treasure” can only be obtained after letting go.

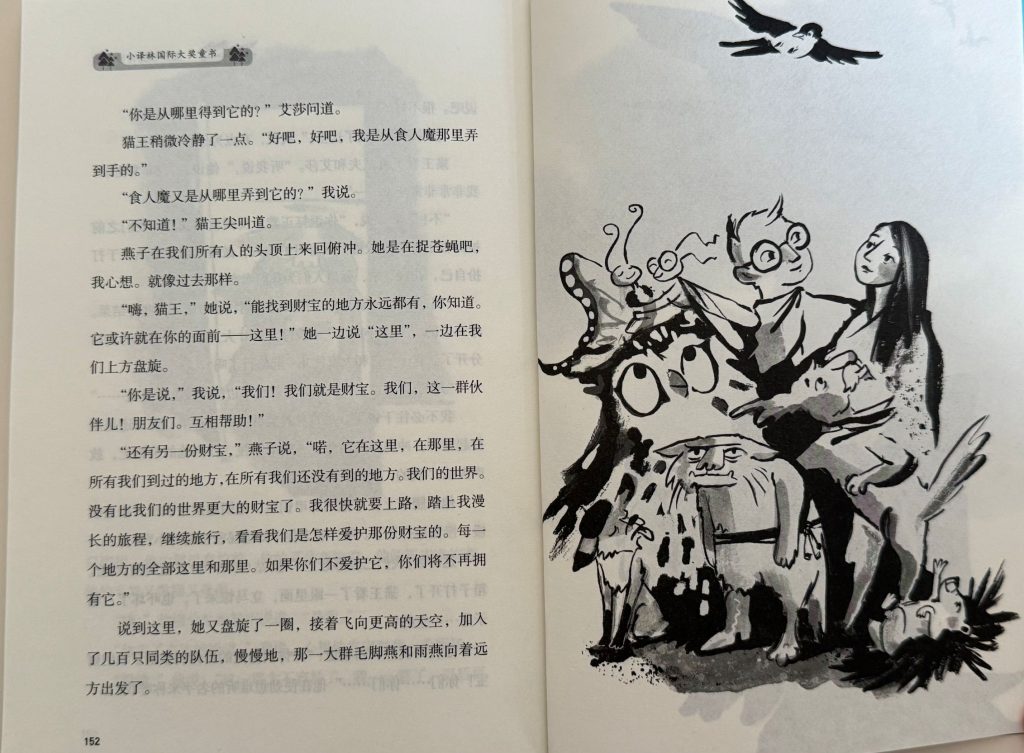

However, what surprised me most about Rosen’s subversion of classic fairy tales was the re-settling of the miller’s son and the princess. Through the cat’s transformation, they were unexpectedly reborn, letting go of all the identities and destinies arranged for them by others. They no longer had to be marquises or princesses, nor did they have to marry a king. They only needed to be themselves, ordinary but carefree Dave and Aisha, self-reliant, and even helping to clean up the garbage in this beautiful world… Thus, Rosen naturally incorporated the increasingly important issue of environmental protection.

Rosen’s handling of the ending is quite bold. Gaston painstakingly returns to the “beautiful” beach of his childhood memories, only to find it littered with garbage and polluted beyond recognition. So, does such an adventure still have any meaning? Can they “live happily ever after”? I think Rosen’s dedicating this story to little Emile must have had a special purpose.

Looking back, the story’s overall tone is humorous and cheerful, full of exotic charm, and for young readers in the English-speaking world, it even serves as a way to learn a little French. It’s worth noting that Rosen has had a strong “French cultural affinity” since childhood. As a child, his parents often took him and his brother to France for summers; one summer when he was 15, he even participated in a six-week summer camp in France alone, speaking and thinking entirely in French, because he personally experienced that some things could only be understood in French!

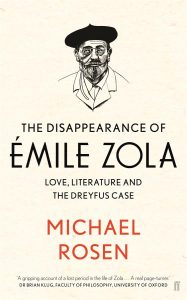

As an adult, he maintained a deep interest in France, and in 2017 he published a unique biography, *The Disappearance of Émile Zola: Love, Literature and the Dreyfus Case*, recounting the life of the great French writer Émile Zola during his exile in England due to his opposition to anti-Semitism. Coincidentally, Zola’s name was also Émile! Rosen dedicated the book primarily to his current wife, Emma, and their two children, Elsie and Emile. In fact, as early as 2008, Michael Rosen was awarded the French Order of Arts and Letters by the French Ministry of Culture for the influence of his work in France.

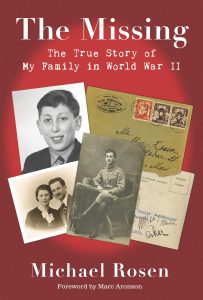

However, the deepest part of his “French sentiment” is hidden in the dedication page of the book recounting Zola’s life: “This book is dedicated to Oscar, Rachel, and Martin Rosen. They perished in an era in France when Zola’s appeals against anti-Semitism were ignored by those in power.” It turns out that Oscar and Martin were Michael’s father’s two uncles, and Rachel was Oscar’s wife. They originally lived in France but disappeared completely during World War II because of their Jewish identity. Michael spent many years searching for them, finally publishing a book in 2020 titled *The Missing: The True Story of My Family in World War II*. In short, Oscar, Rachel, and Martin Rosen all hid in France for a period, but were eventually captured and sent to Auschwitz, never to be heard from again. After years of effort, Rosen persistently traced the escape route of the Oscars: Sedan—Niort—Nice, where they were arrested in the beautiful French seaside city of Nice. The most bizarre thing is that Oscar was born in Auschwitz, and at the end of his life, he “returned home” in such a tragic way—the beginning of life was also the destination of death.

The books mentioned above, along with the story of Gaston the dog, are all dedicated to Emile, demonstrating that this “storyteller dad” is particularly earnest and honest. He doesn’t want to shy away from the potentially unpleasant aspects of real life for his children, nor does he want to weave a “pure and beautiful” fairytale ending. Indeed, it’s a wondrous adventure that can transform an ordinary person into a hero, but it doesn’t promise a happy ending. Returning after getting lost is simply returning to the starting point.

The main significance of this wondrous adventure may simply be that it teaches us what true treasure is. However, as Gaston the dog says, “We still have a lot to do…” but it requires everyone’s participation to achieve “happily ever after.”

Of course, this is also what Rosen wanted to say.

Written by Ajia on August 8, 2025 in Beijing.

Leave a Reply