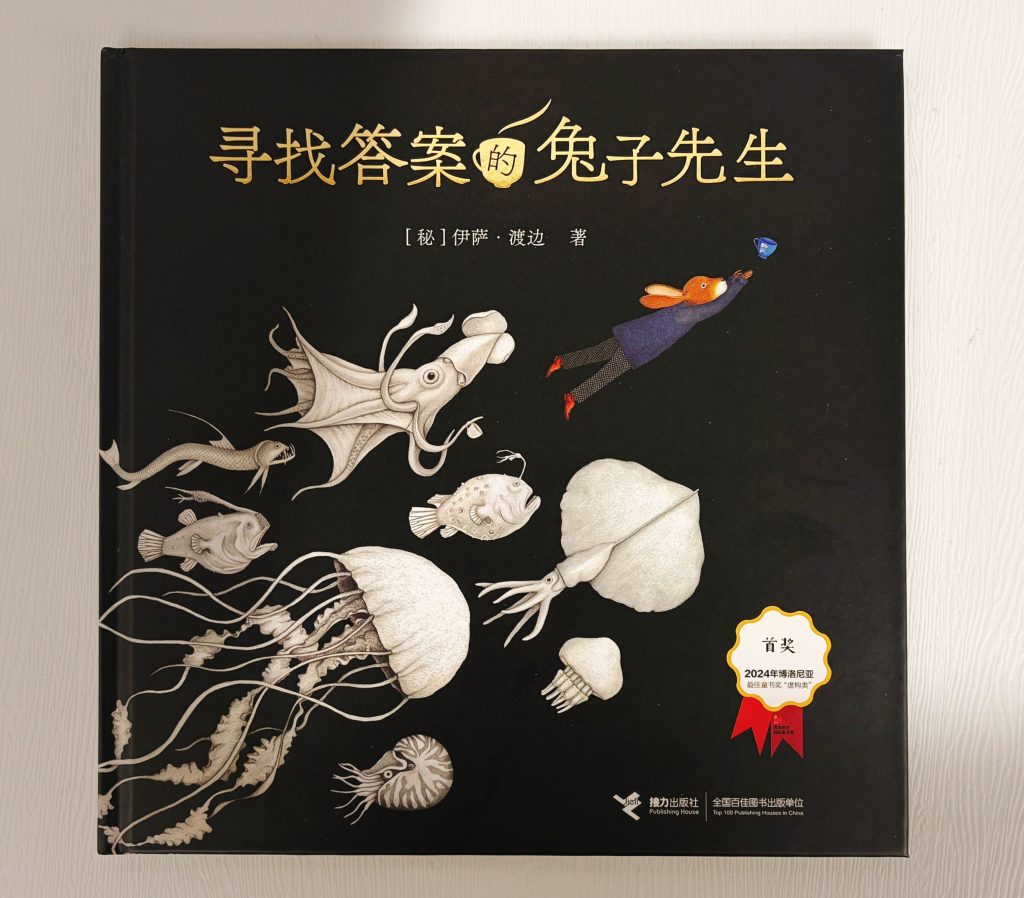

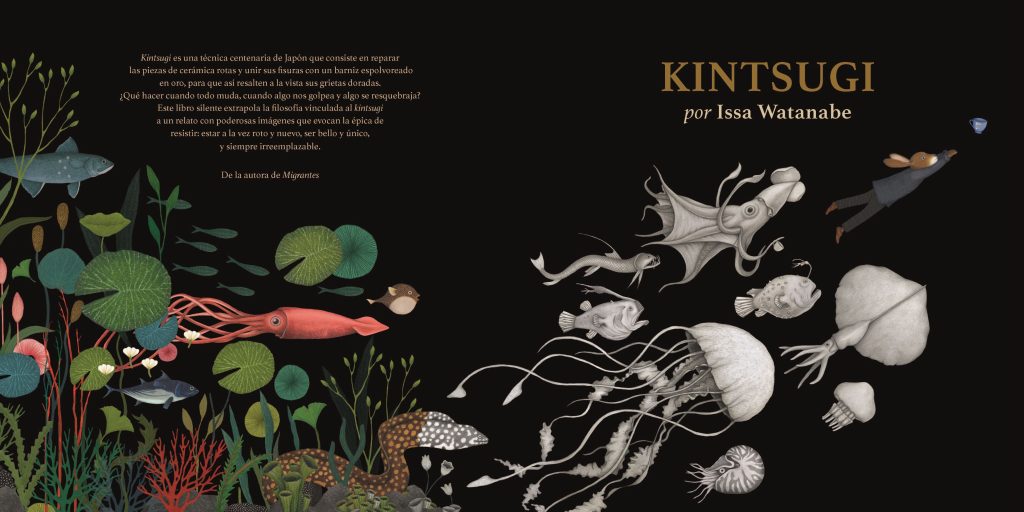

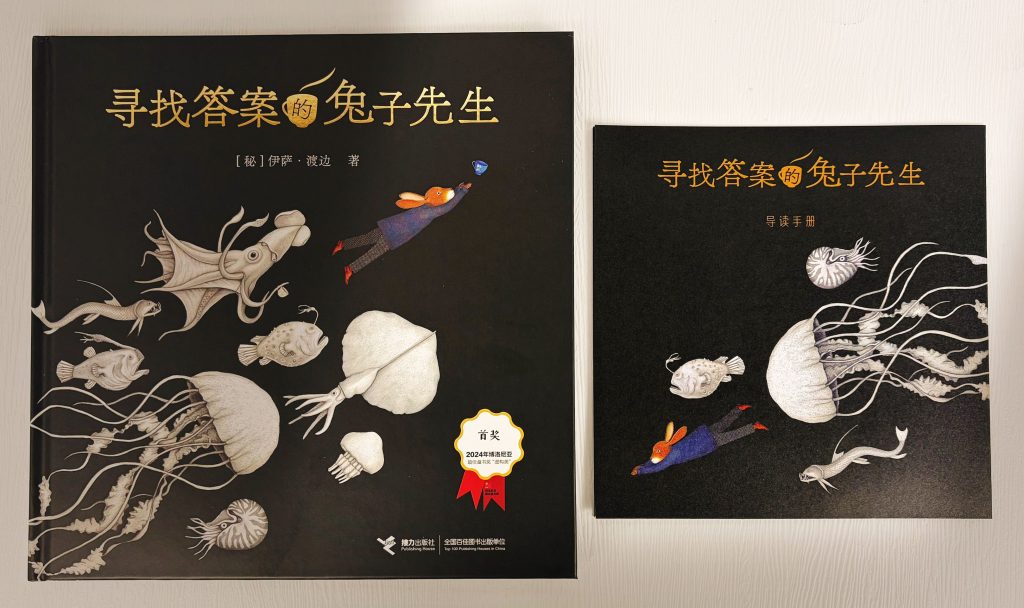

Upon first seeing *Kintsugi* (original title: *The Rabbit Who Searches for Answers*), I was immediately drawn to its striking cover. Against a black background, a rabbit stretches upwards, trying to grasp a blue teacup, which floats away to the upper right. Behind the rabbit, a group of strange-looking white sea creatures follow closely… The simplicity and negative space of the illustration seem to hint at a profound and unsettling story, compelling one to turn the pages and seek the answers.

This is a wordless book created by Peruvian artist Issa Watanabe (1980-), her second book published after the wordless book *The Migrants*. It won first prize in the “Story” category at the 2024 Bologna Children’s Book Fair in Italy. The judges gave it extremely high praise, stating that it “offers a poetic allegory with exceptional tenderness and depth through unique and elegant visual storytelling, confidently and concisely presenting a journey from loss to rebirth.”

Reading this wordless story is both a visual artistic experience and an open dialogue with the soul, inviting readers to participate in the narrative based on their own experiences and insights. The narrator’s “silence” is perhaps its most captivating aspect, allowing each reader to discover their own unique story. The ingenious arrangement of visual details makes the reading process full of exploratory pleasure, while the quote from Emily Dickinson’s poem “The Hope Bird” at the end of the book infuses the entire work with philosophical and emotional depth.

As a book reviewer and an ordinary reader, I also needed to try reading this wordless book several times to feel I could clearly understand the story. I also found that discussing and deliberating with like-minded people (adults or children) helped me understand more. Moreover, I know that the more times I read it and the more like-minded people I involve, the more different versions of the story will emerge. Therefore, the version of the story I’m sharing below is one that I’m currently using. Of course, it’s just one of many possible versions—

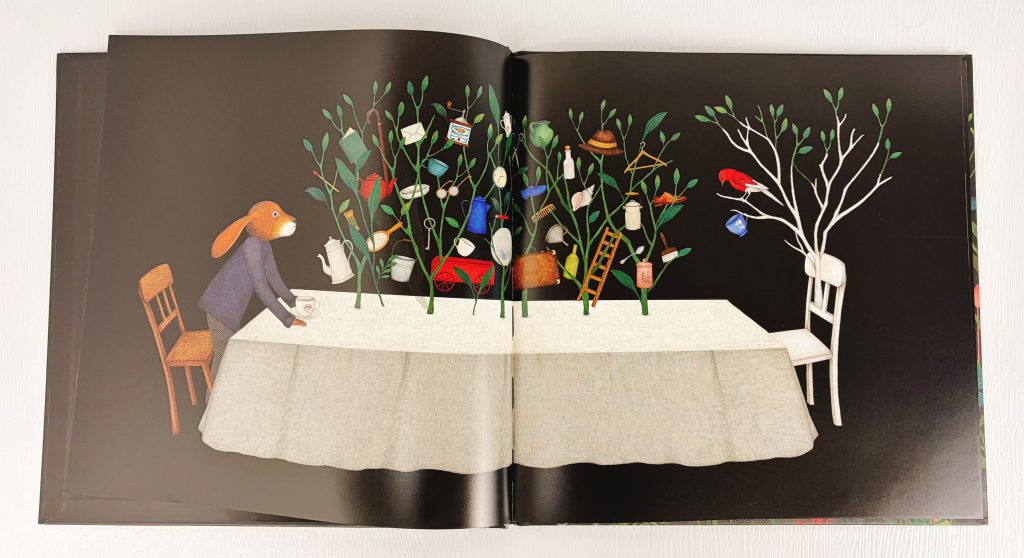

The story begins with the protagonist, a rabbit, carrying two teacups, walking towards a large table. Sharing his tea break is a small red bird perched on a branch opposite the table. This seemingly ordinary tea-drinking scene carries a hint of the strange. Branches abruptly sprout from the tabletop, as if quietly telling a metaphor: daily life is like this table, where people sit together drinking tea and chatting, sharing warm moments, while the branches symbolize the extended events and experiences in life. Everyday objects hanging on the branches, such as a comb, glasses, a teapot, and a hat, seem to bear witness to past happy times. The rabbit, teapot, teacups, and the stopped clock in the picture also inadvertently evoke classic imagery from *Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland*. However, the author cleverly places these items in unconventional locations, subtly stirring a sense of unease in the viewer, making them eager to know what will happen next.

Soon, the scene changed. The red bird looked down at the table, the reflection of the branches on it resembling cracks. At that moment, the rabbit, who was pouring tea, stood up anxiously, ears back, watching the red bird intently. The table, stool, and branches on the red bird’s side, including itself, began to gradually change from color to white. The next scene was intriguing—the white bird suddenly grew a pair of human feet, its right foot draped with the tablecloth, and flew away. The tablecloth fluttered with its ankle, the branches on the table disappeared, and the objects hanging from them scattered to the ground. The rabbit hurriedly chased after it, clutching a small green twig tightly in its hand. This twig had once grown from the branches of the large table, a witness to the past and a symbol of the rabbit’s hope.

The rabbit’s journey was fraught with peril. He encountered a horse gnawing on branches, traversed dangerous Venus flytraps, and finally rowed alone to a patch of dark water. Looking around, he saw only a few solitary icebergs. The rabbit couldn’t find what he was looking for; perhaps the answer lay beneath the icebergs. So, he plunged into the water, and a dark and mysterious underwater world unfolded before him.

For a land-dwelling rabbit, the underwater world was full of unknowns and curiosity. At first, the surroundings were vibrant with color, but as the rabbit moved forward, the creatures of the underwater world quickly turned white again. The rabbit sensed the change in its environment; it swam past white coral reefs, its shoes getting caught and turning white as well. The rabbit struggled to swim upwards, finally surfacing exhausted. It knew that this arduous search would ultimately yield no answers. Fortunately, the small green twig it clutched in its hand was still there; hope remained.

This underwater exploration evokes the feeling of falling into an emotional abyss amidst pain and confusion. The rabbit’s “swimming” into the unfathomable depths is like entering the subconscious world within itself, searching for direction and strength in the darkness. Ultimately, it decides to return to land and confront its shattered life.

Yes, no matter what difficulties or predicaments we encounter, the sun will still rise, even if it only illuminates a mess. At the end of the story, the rabbit returns to his familiar place, gazing at the scattered objects. The items that once hung on the branches are now battered and broken, and the blue teacup in the rabbit’s hand is reduced to fragments. He stops, his ears slightly raised, as if he’s thought of something, and begins to gather the broken pieces, attempting to repair them. A broken stool leg is fitted with a suitable piece of wood, a cup split in two is pieced together with another broken cup, and a bowl and its fallen handle are glued together to become a new teacup… The repaired objects, though bearing their scars, become unique.

Finally, the rabbit inserted the green twig into the repaired teacup, believing that the twig would eventually grow and the items would be hung back on the branches to welcome a new life.

To reiterate, the above version of the story is merely one possible interpretation and retelling. I believe that even I, at a different stage of life and with a different mindset, might interpret it in many different ways. This depends on the memories I choose to compare it with at this particular point in time. As Gabriel García Márquez said in his autobiography, *Living to Tell the Tale*, “Life is not what we experience, but what we remember, and the way we reconstruct it in our memories in order to tell it.” Therefore, it is certain that for the creator, Isa Watanabe herself, there is also her unique version of the story, which may even continue to evolve.

Although it’s a wordless book, with the main story told entirely without text, there are still some words inside, such as the title, title page, dedication, postscript, and publication information. These may actually reveal some interesting information. For example, the original title, “Kintsugi,” also known as “Kintsugi,” is a Japanese technique for repairing broken porcelain using lacquer or gold powder, originating from the Chinese “mending porcelain.” Judging from the author’s surname, “Watanabe,” she clearly comes from a Japanese family. Choosing this particular technique as the title, besides creating new beauty through the repair of broken objects in the story, may also represent her understanding of the “sabi” aesthetic, closely related to Zen philosophy and the Japanese tea ceremony. In repairing, the cracks and flaws are exposed, allowing the reader to appreciate the impermanence of life and the beauty of opportunity that comes with imperfection.

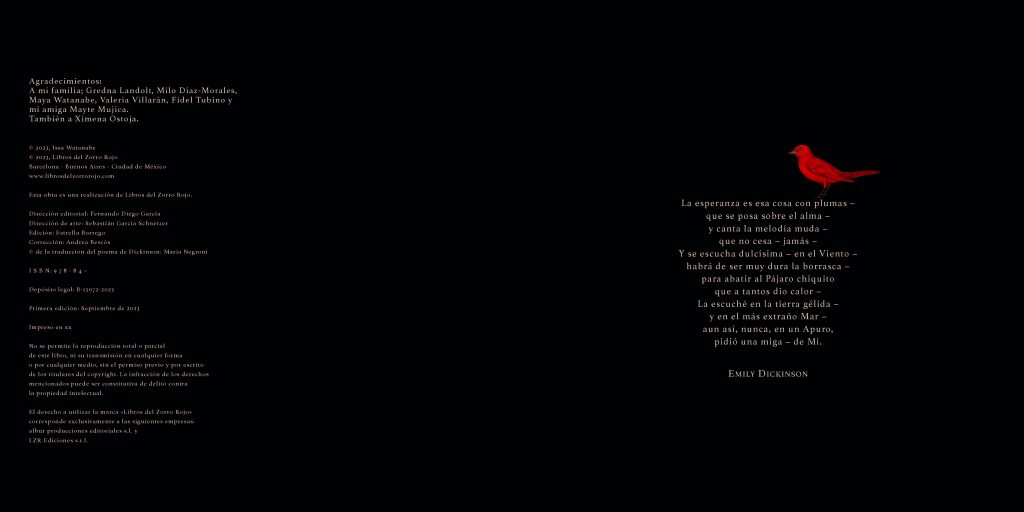

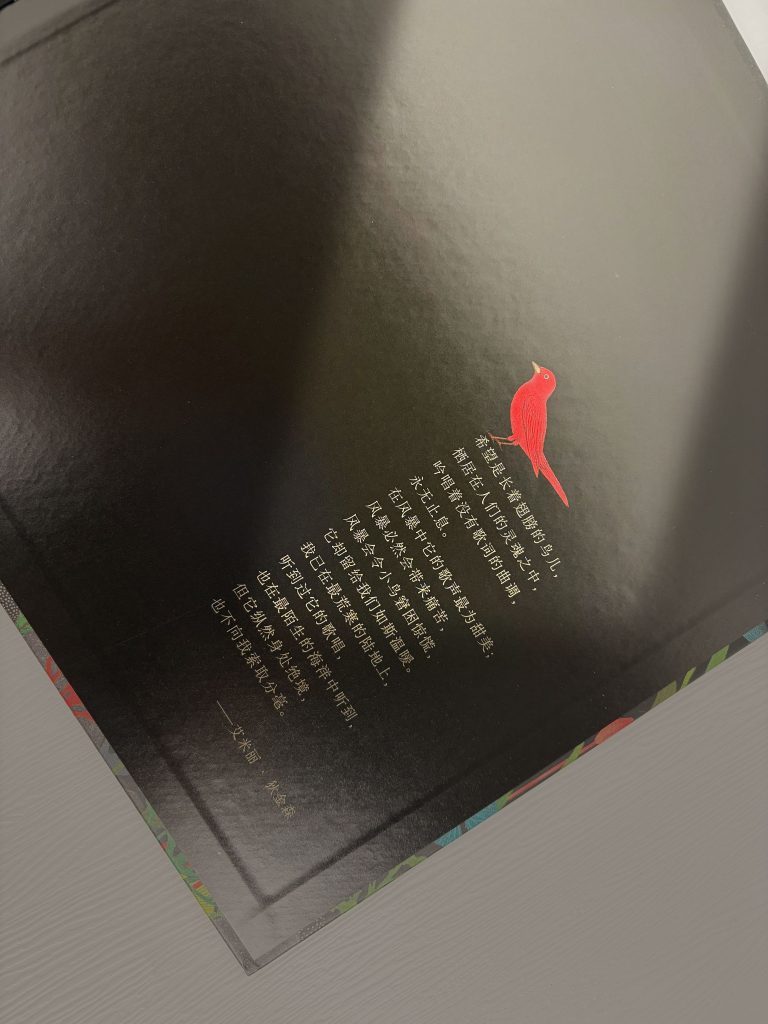

Attentive readers might notice a largely blank dedication page before the title page. Against a completely dark background, it features only a chair, a bird’s nest, an egg, and a few protruding leaves on the left, while the right side simply and solemnly reads, “Dedicated to my daughter, Mei.” Interestingly, at the end of the book, on the copyright page (book information page), there’s a long list of acknowledgments on the left, densely filled with “My Family” and the names of seven relatives and friends, including her sister, Maya Watanabe (1983-), a visual artist. On a separate page on the right, the red bird reappears, but not on a branch; it’s above Dickinson’s poem “The Hope Bird.” Try to guess: what is the connection between the egg and the red bird? And what is the connection between them and “my daughter, Mei”?

Driven by a strong curiosity about Isa’s own version of the story, I extensively researched her background. It turns out she had a poet father and an illustrator mother. Her father, José Watanabe (1945–2007), was a renowned poet and screenwriter in Peruvian literature, and also created some children’s stories. José was of mixed race, but inherited a love for haiku from his Japanese father. His signature Spanish short poems, while not strictly haiku, possess a remarkable simplicity, restraint, and tranquil beauty, and can be seen as allegories depicting the human condition. Perhaps we can also appreciate these qualities in Isa’s poetic graphic stories.

In an interview, Isa mentioned that the inspiration for “Mr. Rabbit Searching for Answers” came partly from her father’s death. At the time, she was living abroad, caring for her newborn daughter, and therefore unable to see her father one last time or attend his funeral. Later, she received a box of items her father had kept, including her childhood toys and a photograph of him holding her, with repair tape on the back. These items became more meaningful in her father’s absence, becoming symbols “representing a person’s presence and absence.” Later, between 2019 and 2020, she experienced a personal crisis; the breaking of everyday objects made her feel unbalanced, and the process of repairing these items gave her the strength to rebuild order. These experiences ultimately transformed into profound metaphors about breakage and reconstruction in her work.

Isa favors wordless books, believing their greatest charm lies in their openness. She hopes readers will fill in the blanks with their own experiences and understanding, constructing the story from within. Her illustrations are filled with symbolic details, especially the use of negative space, allowing readers to discover deeper emotions and meanings. Her creative process emphasizes intuition and improvisation rather than strict planning. She doesn’t start by drawing the entire storyboard; instead, she creates the visual elements of the story first, then freely splices and combines them, letting the story unfold naturally. Every detail in the book is hand-drawn with colored pencils, then freely combined to complete the overall image. She likens this creative method to a child’s unrestrained play, a natural outpouring of inspiration. Isa is well aware that works created in this way might be too personalized to be published, but she doesn’t care, because she believes the creative process itself is more important, helping her heal.

Because of her special concern for children, she prefers to draw animal characters, as animal characters are universal and help stories avoid specific cultural and historical contexts, making the themes more global. At the same time, animal characters can soften serious themes, creating a safe “fictional space” for child readers, making it easier for them to understand complex emotions and experiences.

However, her ability to reconstruct her view of children in her work also stems from her experience as a mother. She frankly admits that becoming a mother was purely accidental; initially, she was quite frightened, but the moment she first saw her daughter, Mei, she fell deeply in love with the child, a feeling that persisted every day afterward. Becoming a mother changed her worldview; she began to rediscover the world through a child’s perspective. This curiosity and wonder at all things influenced her creations, filling them with exploration and insight. Isa dedicated her work to her daughter, Mei, sharing her reflections on life and hoping she could find joy in it. That deep love permeates every detail of her work. I believe that in Isa’s own version, the main theme must be love and hope.

Isa’s quotation of Dickinson’s poem at the end of the book is likely both a tribute to her poet father and a hope for her daughter. The red bird perched on “The Hope Bird” seems to be saying: no matter what darkness and heartbreak one experiences, as long as there is hope, life can be rebuilt.

With love and hope in our hearts, everything can be repaired.

Written by A‑Jia on January 8, 2025 in Beijing

Leave a Reply