These two works, created by a picture book duo from Hong Kong, were born out of the daily grind of parent-child parenting and soar into the imaginative realm of childlike innocence…

*exist“Original Picture Books: Selected Readings and Highlights“In the article, I tried to analyze in detail “Waiting” by the Hong Kong creator Gao Peicong. I am very happy to see that new picture book creation masters are constantly emerging in Hong Kong. The following is another pair of creative combinations worth looking forward to:

“I Want to Raise a Whale” and “The Best Dad in the World” are two works by a picture book duo from Hong Kong, written by writer Liang Yayi and illustrated by illustrator Guo Jingyi. The stories in both books are inspired by the daily lives of parents and children, set against the backdrop of warm family life. Although recorded by mothers, they cleverly draw on the innocence of children. Through innocent and humorous stories and clever narratives, they extend children’s whimsical imagination from the sea to space, from the subtle observations of family life to wild and imaginative fantasies. These books not only resonate with children’s inner worlds, but also contain profound emotional and educational significance.

Ocean of Imagination

The idea for “I Want to Raise a Whale” stemmed from a conversation Liang Yayi had with her three-year-old daughter. Little Cotton, the character in the book, is based on her daughter, representing the innocent child of every child. Upon hearing her mother’s suggestion of “raising a whale,” Little Cotton readily accepted this seemingly absurd suggestion, launching into a series of wild and imaginative ideas. In the final picture book, it’s the girl herself who proposes raising a whale, a natural association with her mother’s suggestion of “raising a goldfish.” Perhaps only such brilliant creativity can match the unbridled imagination of a child. From imagining a whale wearing a crown playing in the grass to planning to take the whale to live under the sea, Little Cotton’s thinking is imbued with the unique logic and humor of a child.

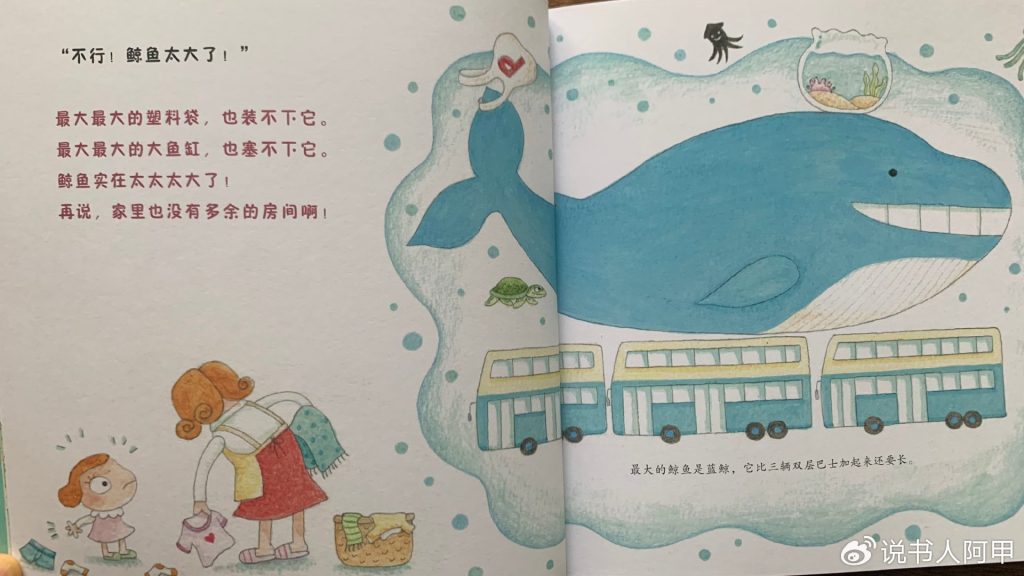

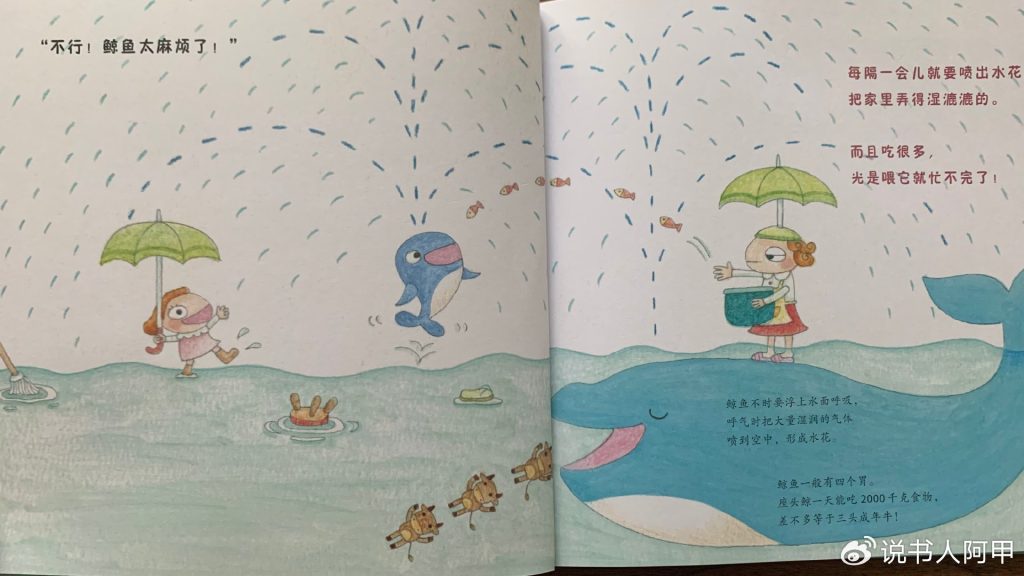

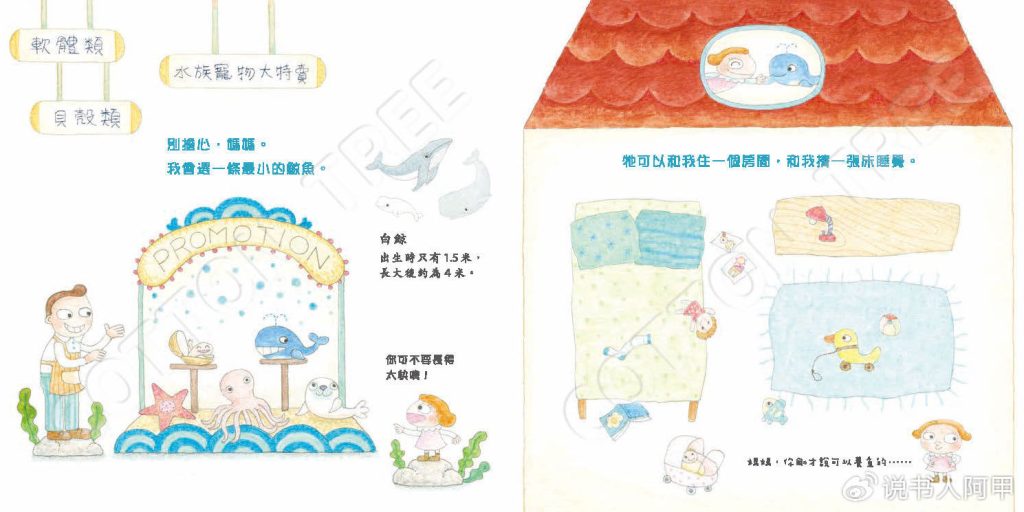

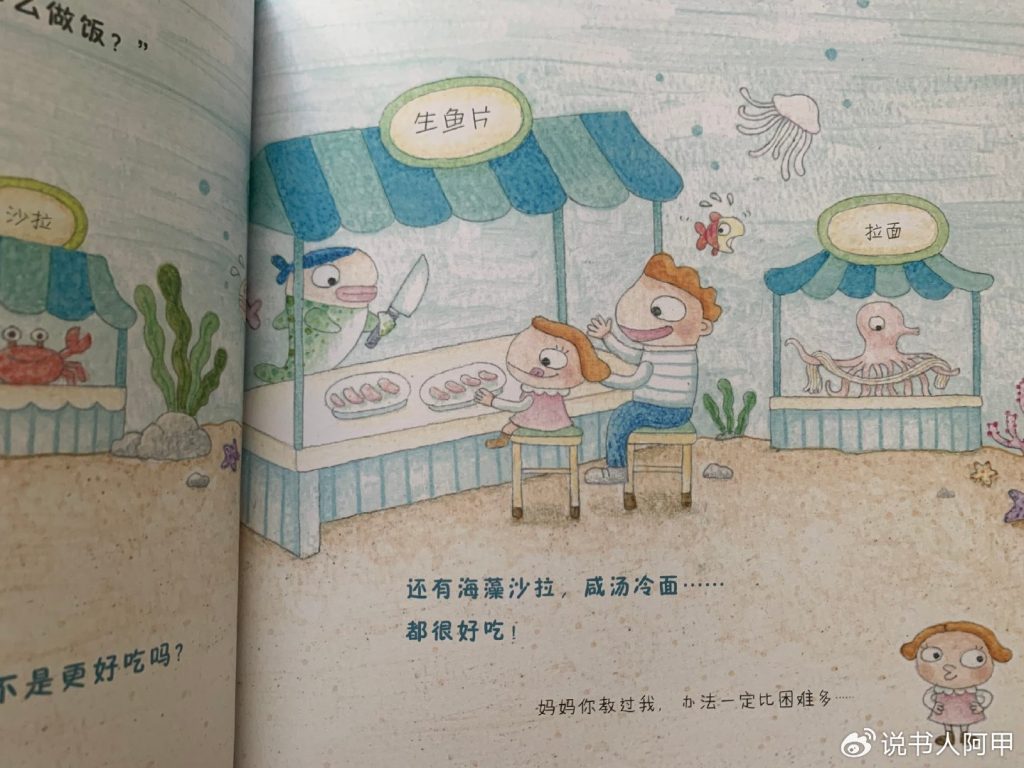

Through the innocent vision of Little Cotton, this book not only captures children’s imaginations but also reveals their simple yet profound understanding of the world. Little Cotton solves problems in her own way—teaching the whale how to spout, arranging a “water tank” at home for the whale to live in, and even considering providing the whale with a healthy carrot diet—all these stories are hilarious, yet deeply moving, and captivating, with the pure and beautiful perspective of a child.

Particularly noteworthy is the harmonious interplay between the book’s text and images, depicting the conflict between fantasy and reality with distinct layers while maintaining the story’s humor and fluidity. Liang Yayi employs simple, child-friendly text. Red font represents the mother’s rational counsel, blue font depicts Little Mianhua’s innocent responses, and the cursive script in the lower right corner includes childish “complaints.” This typographical design clearly captures the rhythm of the mother-daughter dialogue while enhancing the character’s individuality. The narration, in black, regular font, also provides timely insights into marine life, integrating them with the story’s progression, adding a delightful and engaging layer of knowledge.

In terms of visual narrative, Guo Jingyi’s illustrations breathe life into the story. The primary colors of light blue, grass green, and warm yellow create a relaxing and warm atmosphere, cleverly blending the dreaminess of fantasy scenes with the warmth of real scenes. The illustrations are full of details, such as Little Cotton’s room filled with ocean-related books and dolls, and the occasional small fish outside the window hinting at her love for the ocean. The humor presented in the details of the pictures is very strong: the scenes of whales spraying water in the bathtub and sharing food at the dining table are hilarious, and the open ending with the sudden appearance of sharks at the end adds a smile to the whole book.

The super dad who travels through space

The idea for “I Want to Raise a Whale” reportedly originated as early as 2012. However, with the help of an editor, the author devoted himself to learning the unique narrative methods of picture books, pondering and polishing the manuscript for three years before it was finally finalized. With the meticulous collaboration of the editor and illustrator, it was finally published in 2019. Four years later, the duo released their next book, “The Best Dad in the World.” Although a companion piece to the previous one, it doesn’t continue with raising sharks or lizards, nor does it focus on the mother-daughter relationship. Instead, the protagonist is a boy named Xiaoman, showcasing the same tender father-son relationship. The wild imagination remains the same, this time moving from the ocean to space.

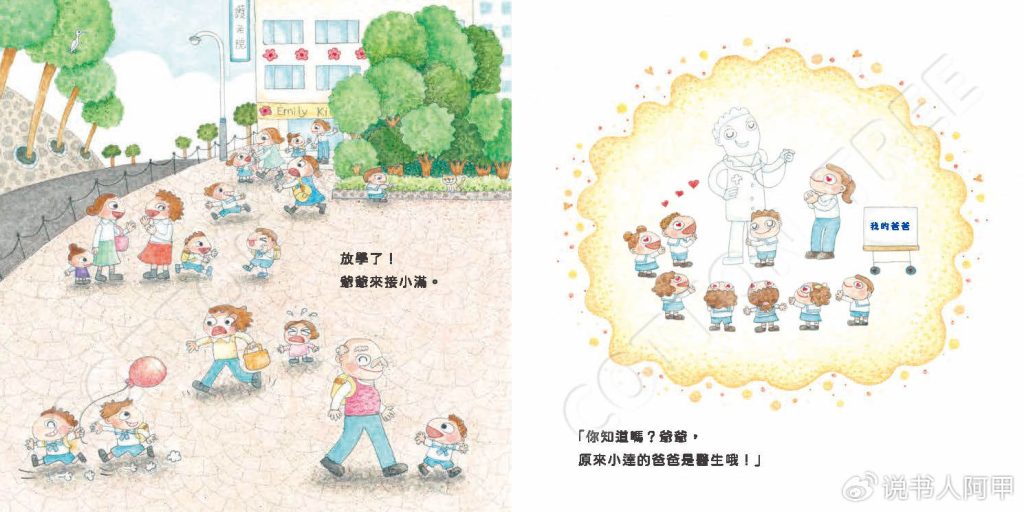

“The Best Dad in the World” begins with a simple, everyday scene: Xiaoman is picked up by his grandfather after school and, on the way home, mentions that a classmate’s father is a doctor. This seemingly ordinary beginning quickly launches into Xiaoman’s world of fantasy. Xiaoman begins to wonder, “What if all dads were doctors?” This highly divergent imagination is extremely childish and truly reflects the admiration a child feels for their parents’ professions. From there, the story unfolds, with doctors, drivers, chefs, firefighters, space architects, and even Superman… A variety of professions take turns appearing, and Xiaoman’s mind constantly constructs interesting and exaggerated scenes.

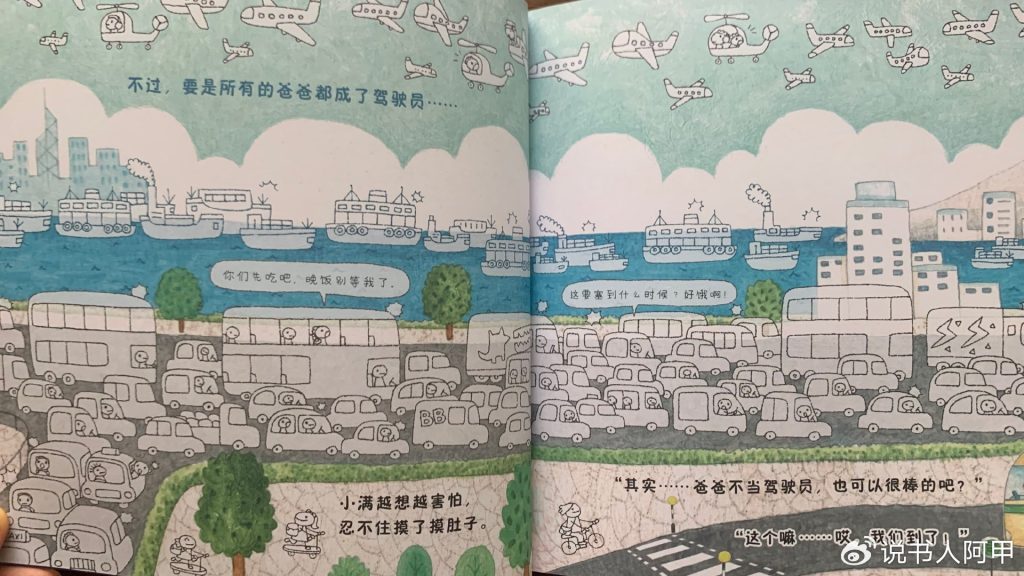

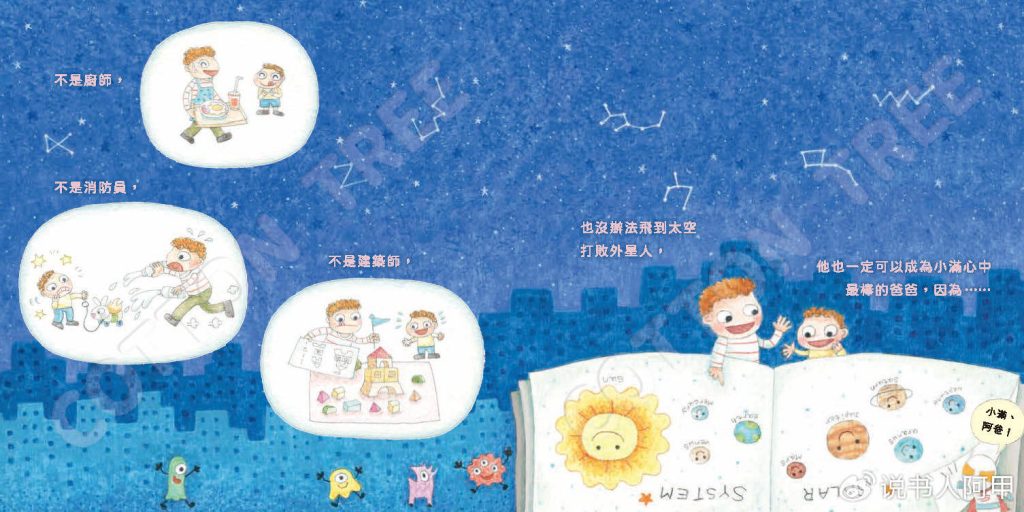

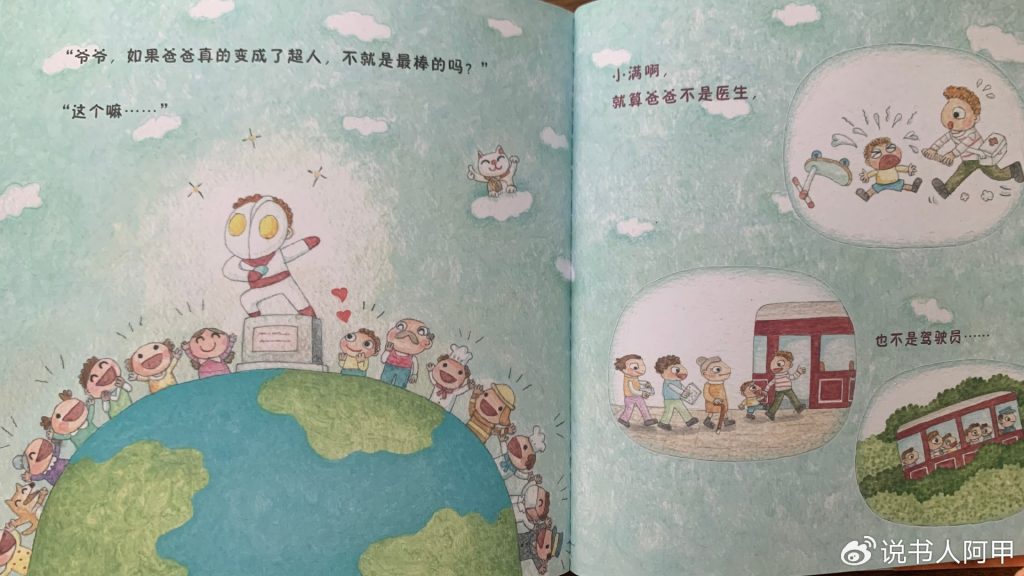

These fantasies are particularly consistent with children’s logic. For example, if dads became doctors, all patients worldwide would be cured, but children might be hounded for injections. If all dads were drivers, the sky and oceans would be clogged with vehicles, but dads might be too busy to return home for dinner… And if all dads became Superman, they would be even more busy protecting the Earth and fighting aliens. These exaggerated fantasy images not only reflect children’s unique way of thinking, but also make the story vivid and interesting, deeply engaging for children.

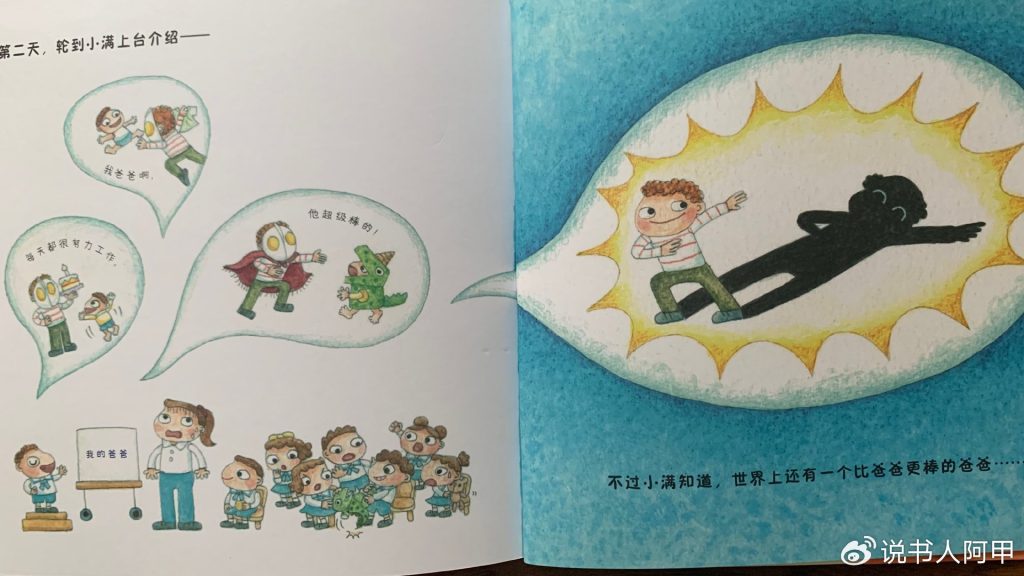

Like “I Want to Raise a Whale,” the narrative utilizes a dual narrative of text and images, creating a rich sense of layering and interactivity. The text uses different colors to distinguish between the voices of the child and the adult: blue text represents Xiaoman’s inner monologue, reflecting his imagination and emotional changes; red text represents his grandfather’s dialogue, full of warmth and guidance, serving as a bridge between fantasy and reality.

The illustrations, alternating between color and line drawings, intensify the contrast between reality and fantasy. In realistic scenes, the illustrations feature soft colors and comfortable compositions, showcasing real-life details like Grandpa holding Xiaoman’s hand and the traffic and pedestrians on the street. Conversely, in fantasy scenes, clean, crisp lines depict Xiaoman’s imagined “professional dads,” such as a busy doctor in the hospital, a driver flying in the sky, and a chef sweating profusely in the kitchen. These dense and rich scenes not only showcase a child’s boundless imagination but also deliver a powerful visual impact for readers.

The text and images complement each other in the narrative, particularly in the transitions between fantasy and reality. As Xiaoman’s imagination spirals out of control, the dense interplay of professional images and the blue fantasy text interweave to create a humorous yet slightly tense atmosphere. However, when Grandpa’s red text appears, the scene returns to reality, providing the child with a warm and nuanced guidance.

A heartwarming presentation of parent-child relationships

What’s most touching about these two books is the incredibly heartwarming parent-child relationships they portray. The mother-daughter relationship in “I Want to Raise a Whale” is both authentic and inspiring. When faced with Little Mianhua’s “whimsical ideas,” her mother neither directly denies nor indulges them. Instead, through humor and patient communication, she guides Little Mianhua to gradually understand the limitations of reality. This equal and gentle approach to education gives children full respect and support, while also allowing parents and readers to experience the wisdom and joy of parenting.

The touching part of “The Best Dad in the World” is that it not only shows the innocence and curiosity of children, but also gradually guides them to understand the essence of fatherly love. Xiaoman’s admiration for his father is expressed through various professional fantasies, and his grandfather’s guidance subtly helps him realize his father’s true greatness. At the end of the story, Xiaoman finally realizes that although his father is not a doctor, driver, chef or superman, he works hard every day and devotes himself to the family. It is precisely because of these extraordinary things in the ordinary that his father has become the “best dad in the world” in his heart.

Excellent combination and clever ending

Both “I Want to Raise a Whale” and “The Best Dad in the World” demonstrate Liang Yayi and Guo Jingyi’s profound insight into children’s psychology and their exceptional creative ability. Drawing from everyday life, they employ children’s language and ways of thinking to construct imaginative stories. These books not only allow children to experience the power of imagination, but also teach parents the importance of support and guidance. From the ocean to the sky, from whales to Superman, these two books, with childlike innocence, reveal the vastness and depth of a child’s world. They are both a wonderful journey for children and a testament to the love within a family.

The endings of both books are particularly noteworthy. The first seems to conclude with a knowledgeable conclusion, but its open-ended ending could potentially trigger a new round of wild imagination. The second seems to end in the style of Anthony Brown’s “My Father,” but it invites new layers and new associations with each turn of the page. It seems this creative duo has endless creative potential, and we can look forward to more excellent works that capture the innocence of childhood.

Written in Beijing on November 9, 2024