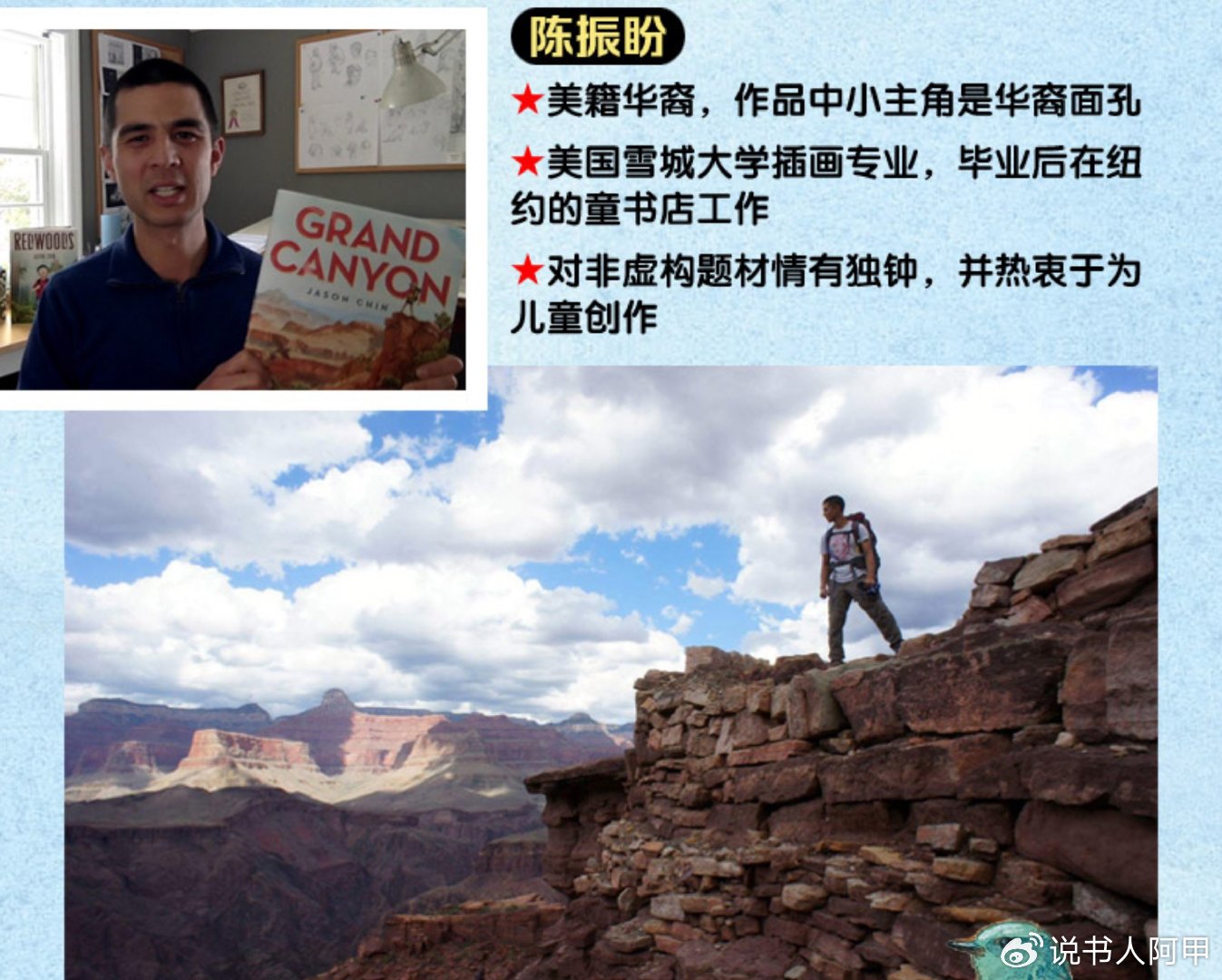

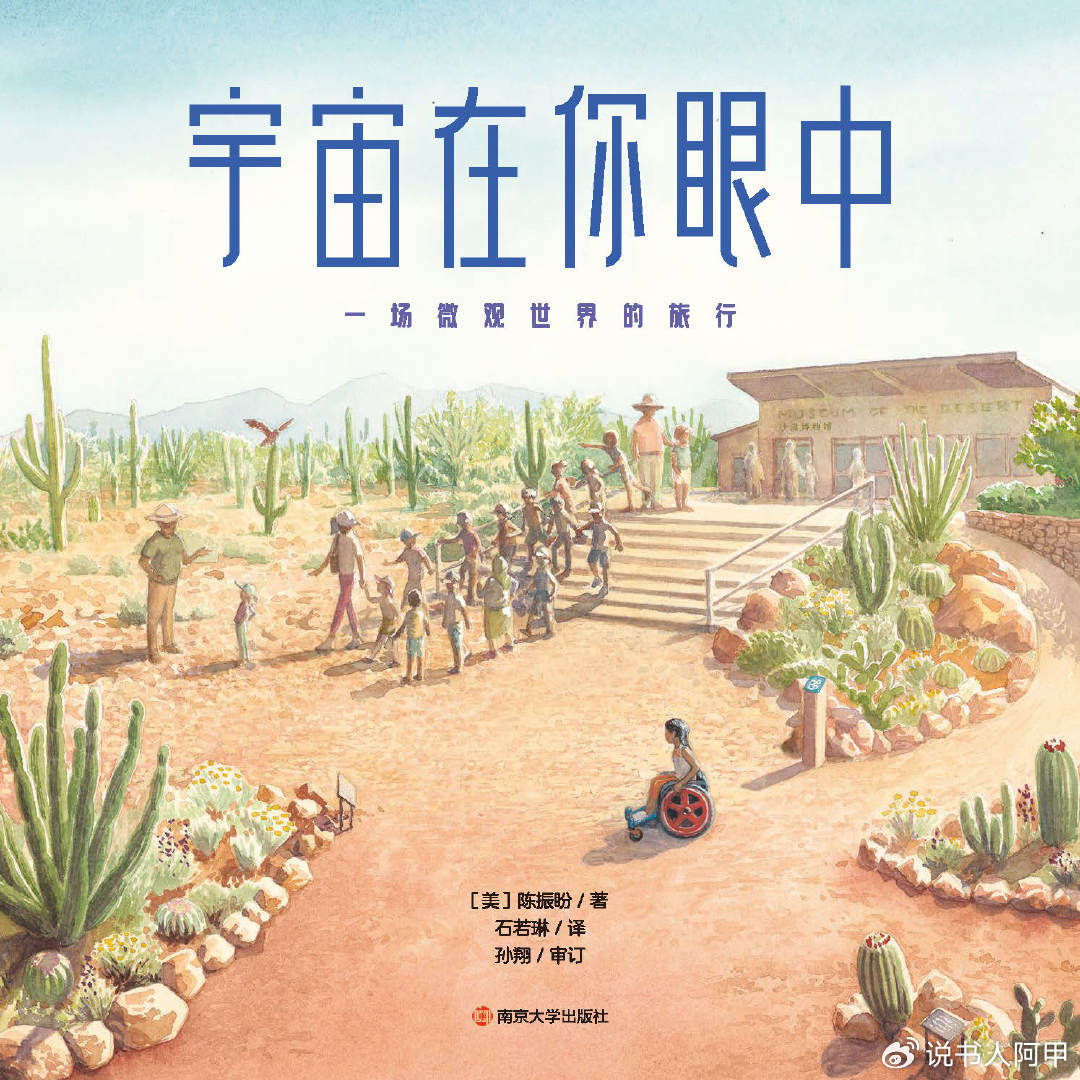

Jason Chin is a renowned Chinese-American illustrator and author who has garnered considerable attention in recent years. He is particularly renowned for his nonfiction picture books with valuable scientific content. His work, “Grand Canyon,” won the 2018 Caldecott Silver Medal, and his fictional picture book, “Watercress,” received the 2022 Caldecott Gold Medal. This latest work, “The Universe in Your Eyes,” explores the microscopic world. With its exquisite illustrations and rigorous scientific content, it guides readers from the macroscopic perspective of Earth to the microscopic world of molecules, cells, and even smaller particles.

This book echoes its companion volume, The Universe and I (2020), which focuses on the vast dimensions from Earth to the cosmos. While The Universe in Your Eyes draws readers’ attention to the invisible, microscopic world, each presenting both the macroscopic and microscopic aspects of the universe, forming a complete cycle of scientific exploration. This new work, however, showcases a fascinating “invisible world” with breathtaking visuals, conveying awe and inspiration for the world and life through a unique exploration method.

The Wheelchair Girl’s Surprising Discovery

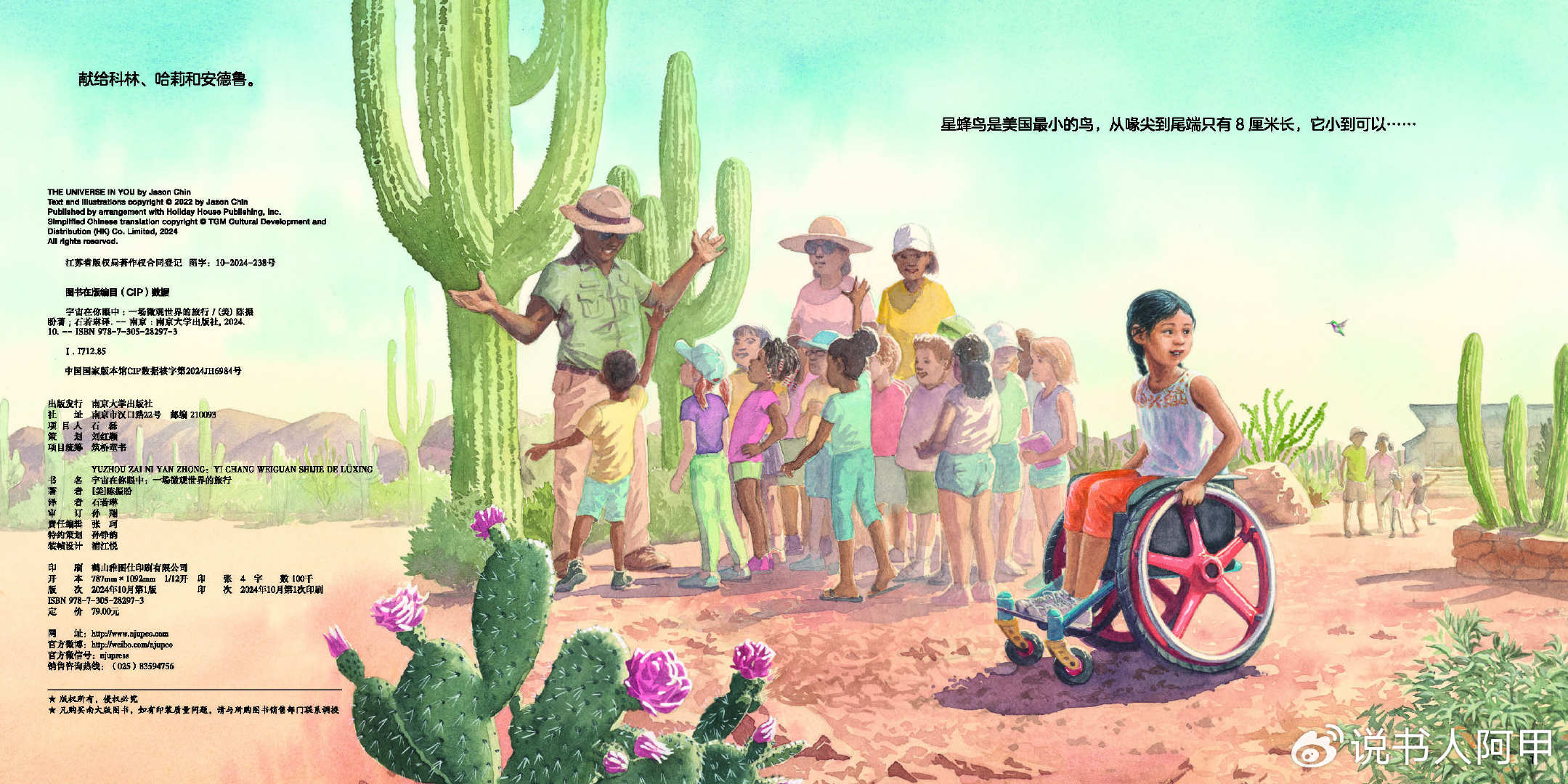

Similar to his signature works like “The Grand Canyon,” “Through the Jurassic Forest,” and “Gravity,” Chen Zhenpan’s science picture books consistently strive to maintain a narrative thread, connecting with readers and drawing them into the wonders of science through the power of story. The protagonist of “The Universe in Your Eyes” is a wheelchair-bound girl who appears to be of Latino or other color. She and a group of other children are leaving a desert museum. She slides down the wheelchair aisle alone, and as she prepares to listen to a lecture, she encounters a star hummingbird. Thus begins her magical journey of discovery…

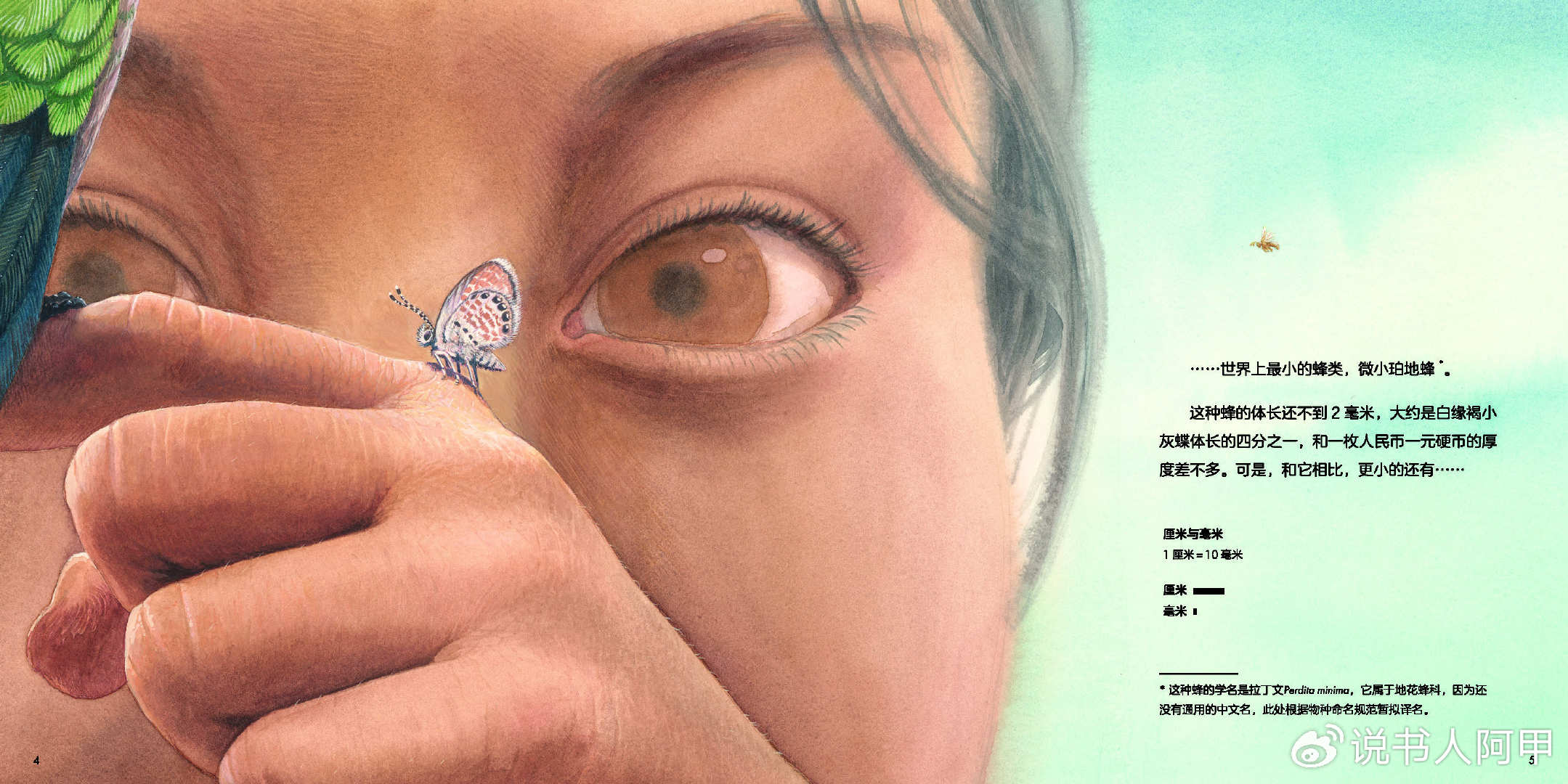

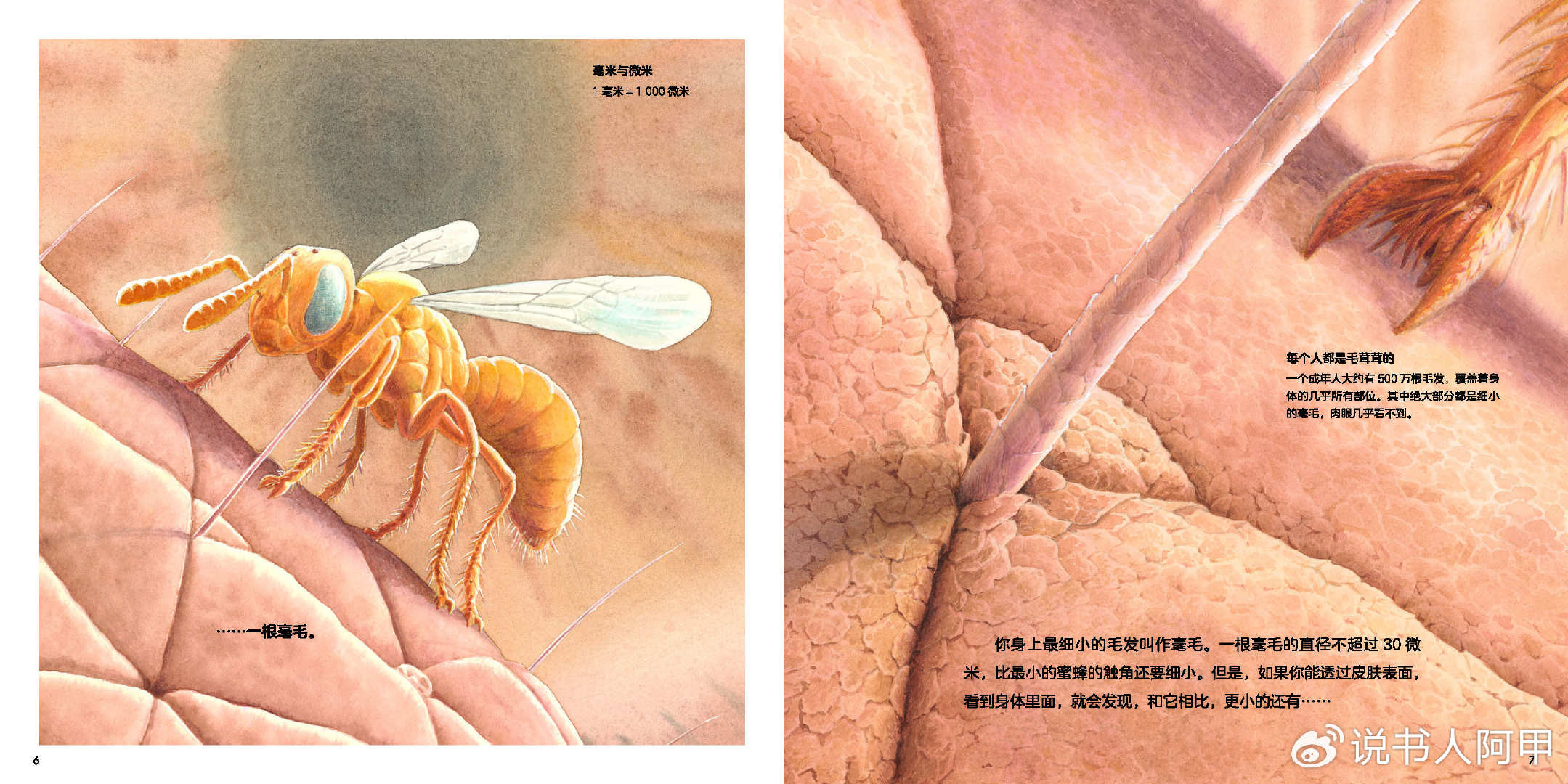

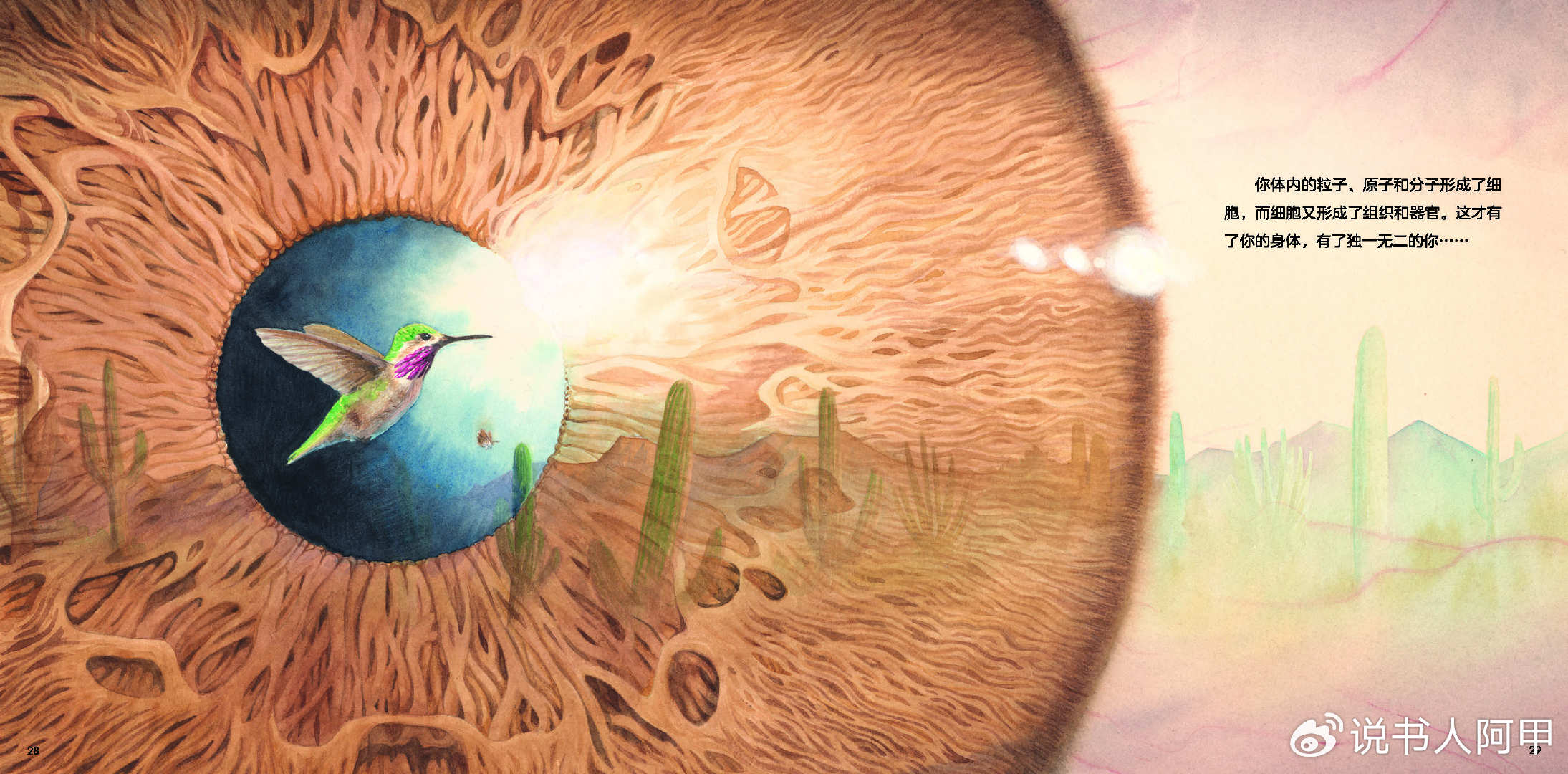

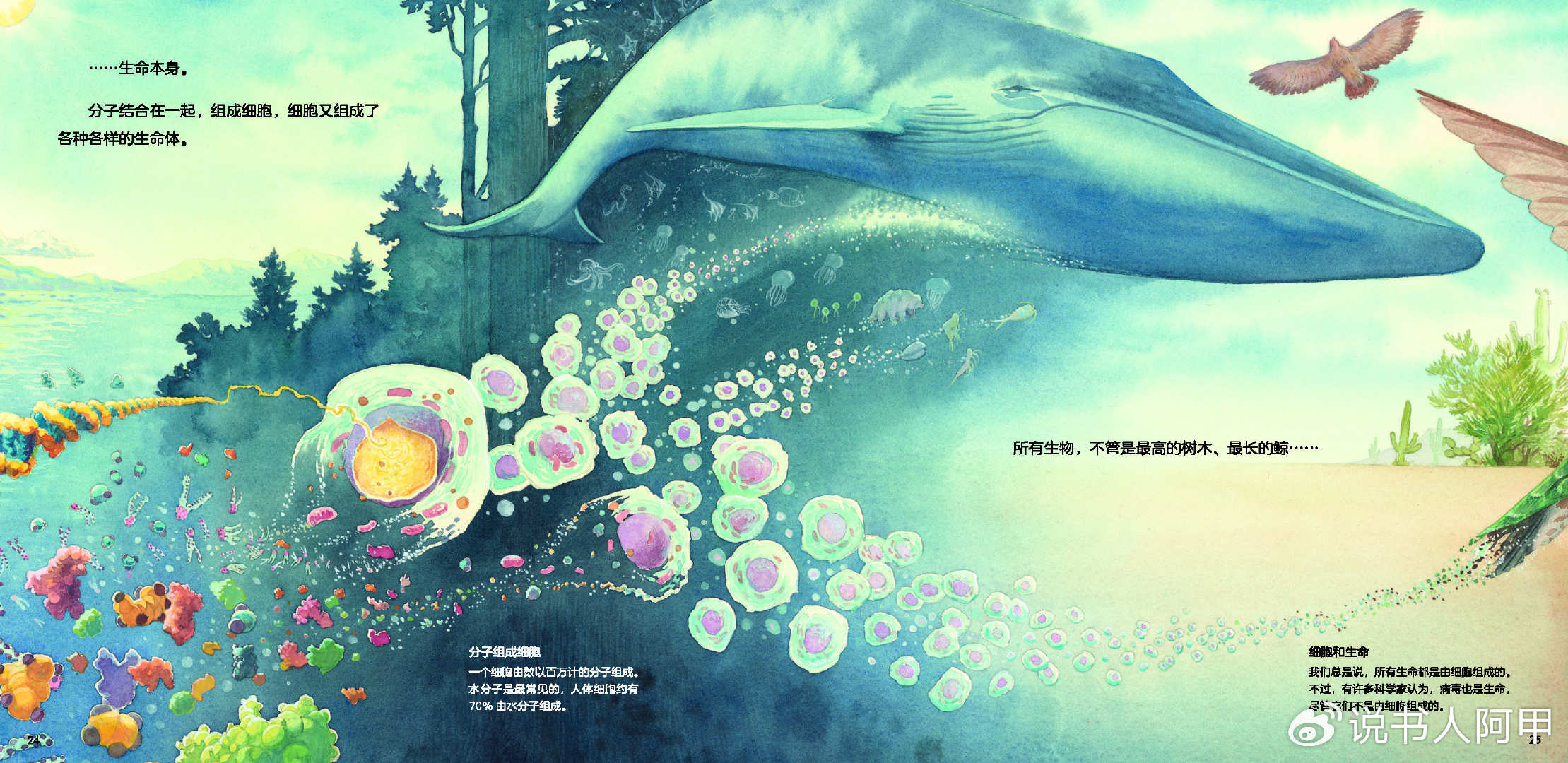

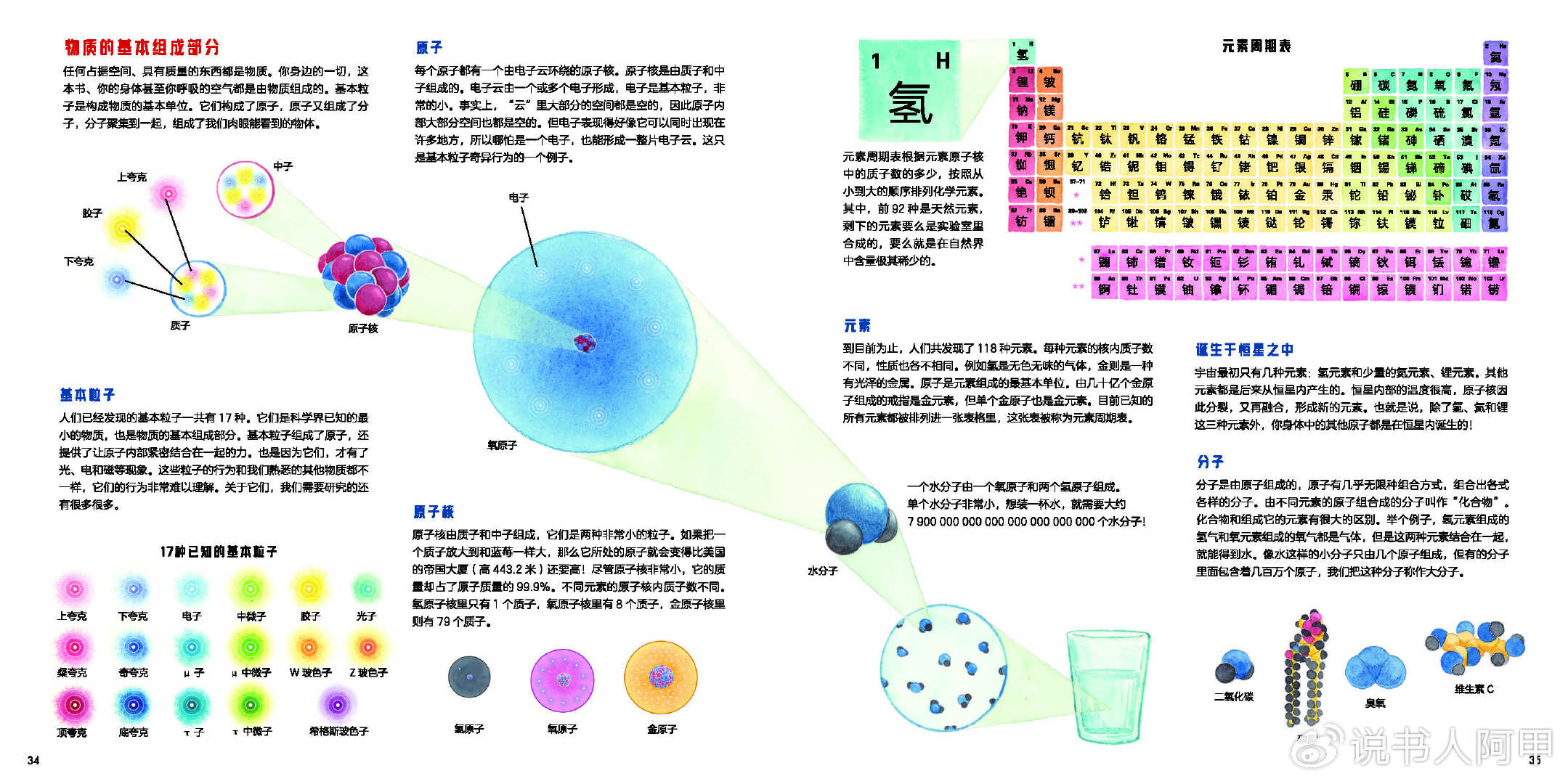

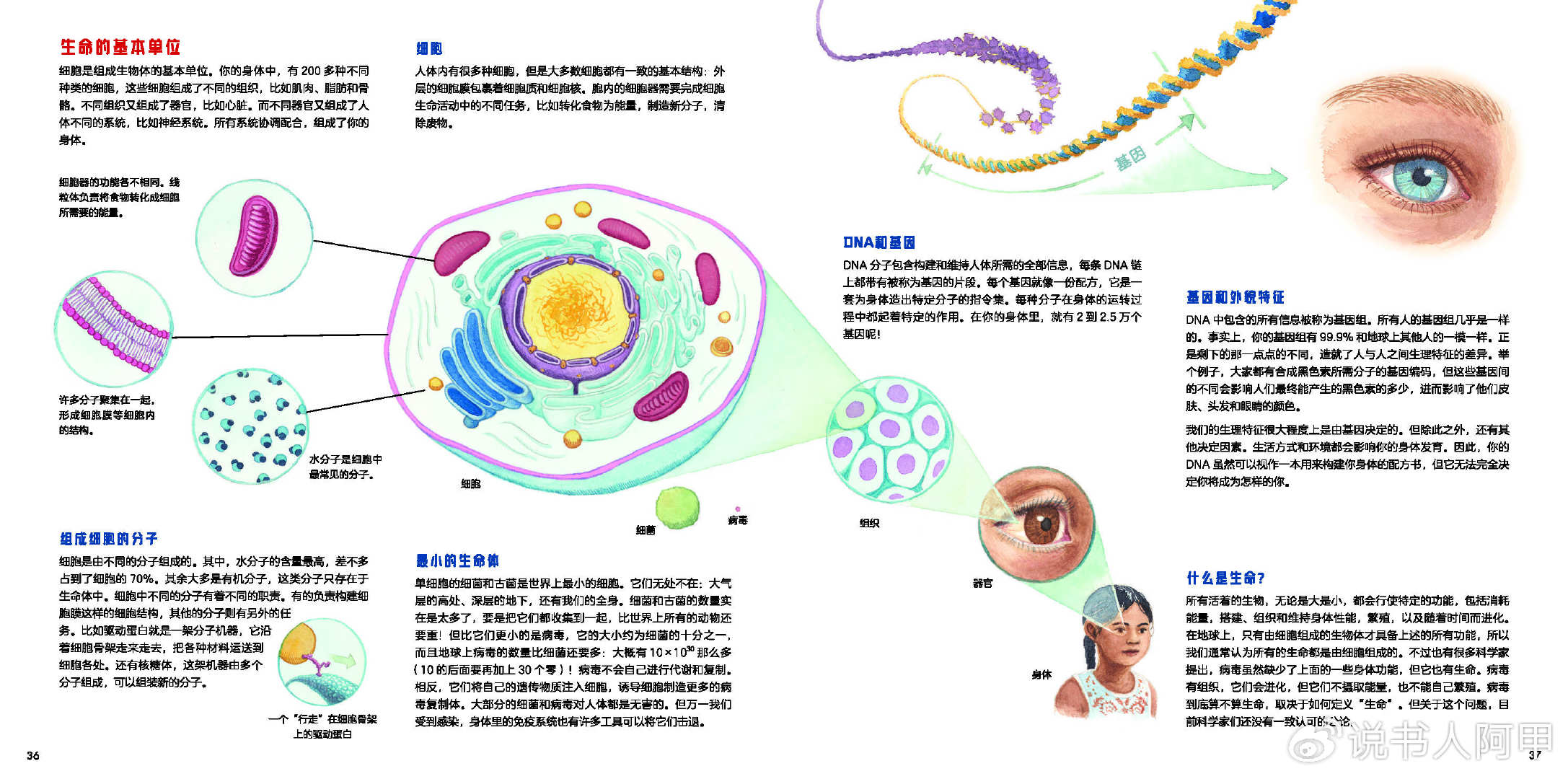

Through the wheelchair-bound girl’s gradual exploration of the microscopic world, Chen Zhenpan presents the vastness of scientific knowledge through delicate visual language and emotional narrative. The book’s main content revolves around the microscopic world, gradually revealing scientific concepts from hummingbirds and butterflies to microscopic particles invisible to the naked eye, such as cells, atoms, and quarks. Remarkably, the book’s content is not presented in a textbook format, but rather, through interaction with the girl, takes the reader on a visual “journey,” gradually allowing them to perceive and understand these invisible things.

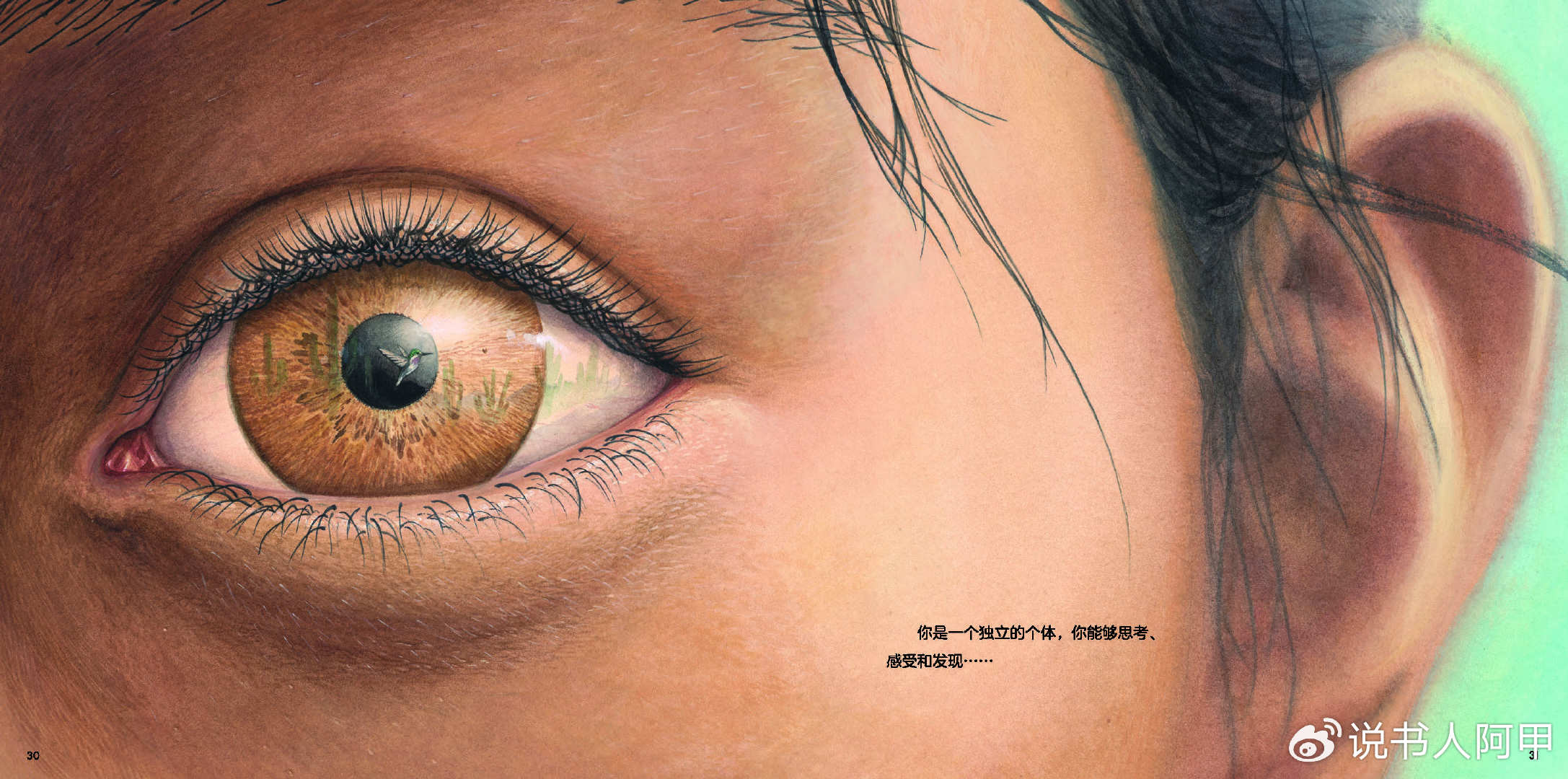

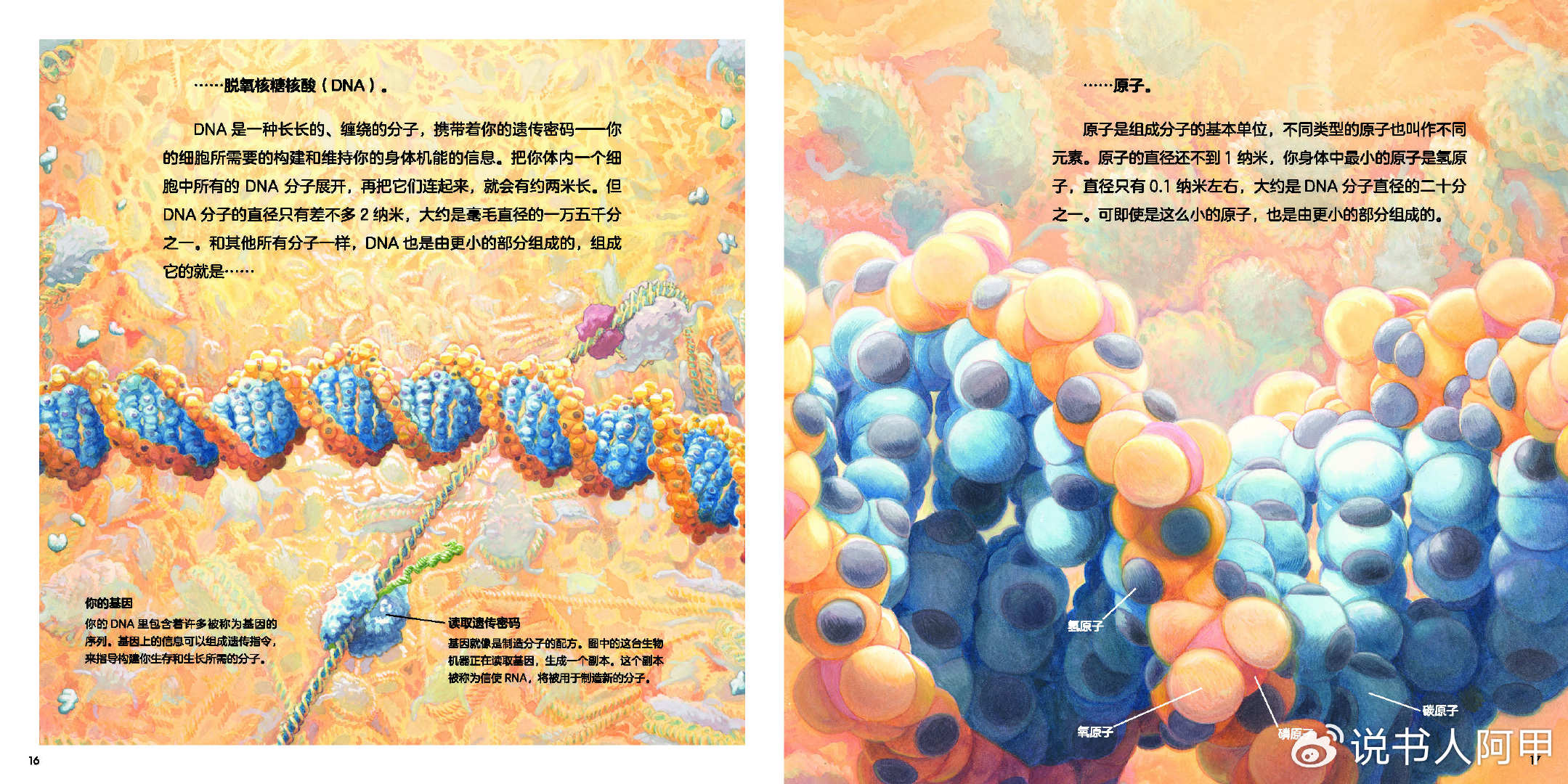

Chen Zhenpan seems to have a knack for capturing the curiosity of young readers. Each double-page spread is filled with surprise, and each one ends with the caption, “But, even smaller than this, there are…” How can you resist turning to the next page?! Technically, the book adopts a progressive structure. Beginning with the macroscopic natural world, the perspective gradually zooms out, guiding readers into the world of cells, molecules, atoms, and even subatomic particles. This narrative technique, from large to small, not only effectively showcases the complexity of the microscopic world but also, through its layered progression, heightens the reader’s curiosity and sparks a desire for deeper exploration. The reader is transported along with the girl’s eyes, journeying from perceptible natural objects to the microscopic mysteries hidden beneath the surface of the everyday world, experiencing the allure of scientific knowledge.

Chen Zhenpan’s meticulous illustration style is fully displayed in this book. Using watercolor as his primary medium, his soft colors and delicate brushstrokes successfully capture the detail and beauty of the microscopic world. The illustrations in this book are both scientifically precise and artistically imaginative. In particular, when depicting cellular structure and particle movement, Chen Zhenpan skillfully blends science and art, imbuing these abstract concepts with visual vitality. Each image is meticulously designed to realistically capture the complexity of the microscopic world while imbuing it with a poetic beauty, allowing readers to not only visually experience these scientific concepts but also experience a dual visual and emotional impact during the reading process.

Unlike typical science picture books, Chen Zhenpan’s paintings possess a unique narrative function. Throughout this book, the illustrations construct a coherent visual narrative through the perspective of a girl, moving from the macroscopic to the microscopic, extending to the entire universe, and finally returning to the girl’s eyes and herself, forming a closed narrative loop. The girl’s facial expressions, hand movements, and interactions with nature and science are all delicately portrayed through the images. This close integration of imagery and story creates an immersive reading experience, as if the reader has crossed the barrier between the macroscopic and microscopic worlds with the girl, experiencing the wonders of science firsthand.

Unique growth perspective

As a rising star of Chinese-American illustrators abroad, Chen Zhenpan caught my attention early on, and I later had the great honor of translating his illustrations for Watercress (written by Chen Yuru). In that fictional picture book, he also chose watercolor as his medium, but experimented with the soft brushstrokes of traditional Chinese landscape painting, creating a dreamlike quality that echoed the story’s deeply reminiscent quality. In this emotional story spanning cultures and generations, he also revealed the unique anxieties of growing up as a descendant of Chinese immigrants, and the creative process itself was a reflection, exploration, and self-healing.

Chen Zhenpan was born and raised in the United States. His father is an immigrant from Guangdong, and his mother is a British immigrant from generations prior. As a child, he experienced identity anxiety due to his Asian features. However, his relaxed family upbringing and his parents’ multicultural education helped him develop a diverse perspective. More importantly, his family enthusiastically encouraged his love of painting, which also fostered a special love for outdoor exploration. He enjoys reading popular science, but his passion for science fiction is even greater, with a particular fondness for “Star Wars.” These encouraged childhood interests gradually converged to shape him into a unique individual.

In his Caldecott Medal acceptance speech, he fondly recalled the influence of fellow Caldecott Medalist and predecessor Trina Schatt Heiman (1939–2004, illustrator of “The Knight and the Dragon”). Trina had given a speech at his school, and he was amazed to see that another “person who loved to draw” could achieve such remarkable success. While in high school, he even made a point to visit Trina’s home nearby. He couldn’t stop talking about his passion for drawing and science fiction, and Trina expressed great interest, as if to tell the young man, “It seems we have similar interests!” Chen Zhenpan studied illustration at Syracuse University and, after graduation, studied painting for a period under Trina. While the average reader might consider Heiman an illustrator specializing in fantasy, Chen Zhenpan was even more impressed by her ability to capture character and detail in her fantasy stories.

In an interview, Chen Zhenpan also mentioned another Chinese artist, Yang Zhicheng (1931–2023), as one of his most admired predecessors. However, he also admitted that while he greatly admired Yang, he never understood Yang’s work the way he understood Trina. He simply longed to create like Yang, and perhaps “Watercress” is, in some ways, a tribute to that Chinese predecessor.

In general, Chen Zhenpan’s artistic approach is more Western. For example, he must be able to “see” what he depicts. This is why, when he wanted to paint “Grand Canyon,” he had to pack his backpack and visit the Grand Canyon in person to sketch it, or at least take enough photos first. For objects he couldn’t see in person, such as the wildlife in the Grand Canyon, he also needed to find solid visual references to confidently recreate them. Although his storylines can be fanciful and imaginative, the elements used to restore scientific facts must be “visible.” This is probably the main reason why his illustrations have a uniquely scientific quality.

“Seeing” the invisible world

However, “seeing” the microscopic world, invisible to the naked eye, posed a significant challenge for Chen Zhenpan. Initially, he planned to write “The Universe in Your Eyes” alongside “The Universe and Me,” a comprehensive exploration of the cosmos. However, as he progressed, he realized that the microscopic world itself possessed rich content and profound philosophical implications, and so he decided to separate the book.

In order to accurately present these complex scientific concepts, Chen Zhenpan not only consulted a large amount of scientific literature, but also conducted in-depth discussions with scientific experts to ensure the scientific nature and rigor of the content. For example, he referred to scientific materials in multiple fields such as molecular biology and cell biology to ensure that the details of cell structure, molecular operation and other details presented in the book are accurate. In addition, in the process of presenting the microscopic world, he not only needs to consider scientific accuracy, but also needs to vividly present these boring scientific concepts to children readers through art. He said in an interview that in the process of creating this book, “I read a lot of books. But in the process of reading, I will do a lot of imagination or visualization. I will visualize what I read in my mind. Sometimes, I will have some strange associations. But you know… maybe these associations are not so strange.”

Chen Zhenpan’s creative process is truly meticulous. By artistically presenting microscopic particles invisible to the naked eye, and leveraging the transparency and layering of watercolor, he allows readers to experience invisible entities such as cells, molecules, and quarks in a more vivid and vivid way. His meticulously designed illustrations depict the texture of cell membranes, the arrangement of DNA helices, and the movement of quarks, all imbued with artistic imagination while retaining scientific precision. The accompanying information and references are excellent supplementary learning resources in this field. It’s no wonder that science teachers in American schools particularly favor Chen Zhenpan’s books!

Diversity and Inclusion

While Chen Zhenpan’s science picture books are also suitable for young people or adults interested in the topic, he primarily creates them for children, so he places special emphasis on conveying relevant concepts. The protagonist in this book is a girl of color in a wheelchair, a setting that is particularly striking. Chen Zhenpan consciously introduces multiracial and multicultural characters in his work, allowing more readers to experience the power of inclusion and diversity. This character setting not only adds layers to the story but also conveys an important message:Science belongs to everyone. Regardless of background, race, or physical condition, everyone can discover their connection with the universe through scientific exploration.

The story’s setting in a desert environment is also a remarkable choice. Deserts are often associated with desolation, but in the book, this environment contrasts sharply with the richness and diversity of the microscopic world. Through this contrast, Chen Zhenpan skillfully demonstrates that even in seemingly ordinary places, a mysterious and vast world of science awaits exploration.

Scientific exploration and fantasy go hand in hand

As an accomplished Chinese-American illustrator, Chen Zhenpan’s own personal journey and creative experiences offer powerful insights. Perhaps the most valuable lesson is the connection between scientific exploration and fantasy. While scientific exploration requires rigorous thinking, it also requires a rich imagination. Through his work, Chen Zhenpan demonstrates the power of combining science and fantasy. His upbringing teaches us that science is not necessarily sterile, but rather filled with endless possibilities and boundless beauty.

“The Universe in Your Eyes” demonstrates this through beautiful images and rigorous scientific knowledge:We can “see” (discover) the invisible world through science, but this is inseparable from the support of curiosity and imagination.Such works give children wings to explore science, encouraging them to find a balance between rationality and sensibility, to use scientific tools to understand the world, and to use the power of imagination to explore the unknown.

Argentine Primera División written on October 14, 2024 in Beijing